by Wilhelmina Randtke, Randy Fischer, and Gail Lewis.

Introduction

The Florida Academic Library Services Cooperative (FALSC) provides digital library hosting free-of-charge to all institutions of Florida public higher education. Through this program, 21 institutions participate in the Islandora digital library platform hosted through FALSC. Centralized digital library hosting through FALSC, or its predecessor consortium, has been available since 1994. Meanwhile, the RightsStatements.org standard, which provides a controlled vocabulary for indicating the copyright status of digital library material, was released in 2016. After the standard was released, participating libraries expressed interest in implementing RightsStatements.org for the large backlog of existing digital content hosted through FALSC. During Fall 2018 and Spring 2019, FALSC implemented the RightsStatements.org values on Islandora sites. This involved:

- Adding the standard to FALSC’s local Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS) metadata profile.

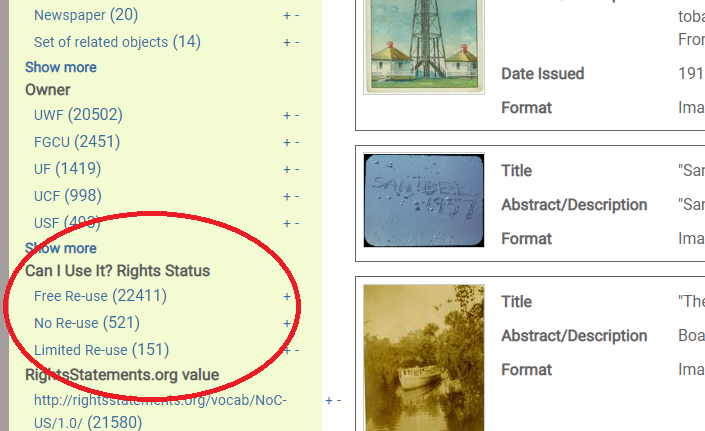

- Configuring Solr such that the search results can be meaningfully faceted by reuse rights. There are 12 possible RightsStatements.org values, which can be confusing and difficult for researchers to understand. Through group meetings and dialogue between member institutions, these were grouped into 3 categories of reuse: Free Re-use, Limited Re-use, and No-Reuse. Solr indexing was configured to allow users of digital library sites to limit search results by those three manageable categories and allow researchers using the digital library to quickly find materials which can be reused for presentations or to create open educational resources.

- Adding the RightsStatements.org values to metadata forms available to librarians and others adding material to the Islandora platform.

- Assisting member libraries in implementing the RightsStatements.org values by sharing existing training resources from other groups, by providing Excel spreadsheet reports of digital library metadata to assist libraries in quickly working through materials, and by coding a batch insert to allow libraries to return a completed Excel spreadsheet and have FALSC add the values to existing Islandora materials.

From the time FALSC’s batch insert code became available in February 2019 through the March 2019 conclusion of the first push to add RightsStatements.org values, the standardized copyright statements were added to approximately 60% of public materials in Islandora not coming through Florida State University (FSU), the largest participating digital library.

This paper provides information on the way RightsStatements.org values were grouped into broader, easier-to-understand reuse categories for end users and the process of communicating with libraries to empower each library to add copyright statements to a large amount of existing content. It also includes recommendations on improving the process, including addressing a digital library collection-by-collection versus item-by-item and a strong recommendation to approach RightsStatements.org by simultaneously adding a more detailed copyright statement showing the logic behind the controlled statement in order to “show your work” so the end user can more quickly confirm whether or not material can be reused.

Background on RightsStatements.org

What does RightsStatements.org do?

The core of RightsStatements.org values is that they are computer readable markup about copyright status and that they aren’t licenses. A RightsStatements.org markup on a work is a URI referencing a URL which says something to the effect of: This is what we believe the copyright status of this work to be, and here are several disclaimers that this might not be accurate and you may want to do your own additional research to verify this.[1] The RightsStatements.org values are similar to the established Creative Commons licenses.[2] The Creative Commons licenses allow an author or creator of a work to attach a license onto the work in standardized markup, which can be read by a computer. The RightsStatements.org values perform a similar function, showing copyright status, but are not licenses and specifically sidestep promises and legal liability.

The RightsStatements.org statements are a standardized markup that can be applied to items which a library has digitized from its collections without the library needing to own the copyright to the item. In contrast, a license requires ownership of the copyright in order to grant a license. So a Creative Commons license would have to be applied by the author at the time the material is given to a library or the author would later have to be contacted to provide the license. For the vast majority of digital library content, licensing is impractical or impossible. For older materials, the author may be deceased. Even materials with a living author have likely been collected without the library or archive simultaneously getting a license. Comprehensively implementing Creative Commons licenses across all digital library material is not feasible.

Any computer applications supported by computer-readable Creative Commons licenses can be supported by RightsStatements.org statements. And because the RightsStatements.org statements can be applied by a library to a backlog of materials without any action by the authors of those materials, there is a possibility of quick and comprehensive adoption for cultural heritage materials in digital libraries.

By being computer-readable, the RightsStatements.org statements theoretically allow for faceting by reuse rights similar to that allowed by Creative Commons licenses in searches like Google Advanced Search.[3] RightsStatements.org is also interoperable with Creative Commons licenses. Both can be used across a set of records, with Creative Commons in use for items which can be licensed and RightsStatements.org in use for items which are marked up by someone other than the author and therefore can’t be licensed.

History of the RightsStatements.org standard.

Europeana[4] is a massive centralized federated search of digital library materials in Europe. RightsStatements.org is a relatively recent standard compared to Creative Commons, which was released in 2002.[5] In April 2016, the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) and Europeana jointly launched RightsStatements.org and the RightsStatements.org controlled values.[6] At the time of launch, both federated search projects emphasized a RightsStatements.org value as a pending future requirement for all items contributed to DPLA or Europeana. In the case of DPLA, this requirement is coming soon with many contributing digital libraries a in the process of implementation. In the case of Europeana, the requirement was to have either an existing statement in the Europeana Licensing Framework or to have a RightsStatements.org value.

As of 2019, Europeana is the only major digital library search to use the RightsStatements.org values as part of the interface. The history of Europeana, including the early standardization of copyright statuses within Europeana materials in 2012 using the Europeana Licensing Framework, is the most likely reason for this.[7] Before RightsStatements.org was released, Europeana had a critical mass of existing items with a controlled copyright statement in the Europeana Licensing Framework and so contributing digital libraries had existing statements that could be mapped to or combined with RightsStatements.org values. Significantly, not all items in Europeana have a controlled rights statement. As of June 2019, running searches on Europeana will result in more “hits” than are available by summing together rights statements statuses within that set of hits (i.e., a search locating 290,000 hits might have 287,000 hits with a copyright statement and a handful of hits without). Running searches which retrieve a large number of hits and examining facets by copyright status reveals that many existing statements in Europeana are “Copyright Not Evaluated.”[8] Nevertheless, Europeana has a critical mass of controlled copyright statements to allow meaningful faceting by reuse rights and has incorporated those into the search interface.

You can see this by going to Europeana’s search portal at https://www.europeana.eu/portal/en and running a search. Along the left hand side of your search results, there is a facet for “Can I Use It?” This facet is built on the controlled rights statements and maps both Creative Commons licenses and RightsStatements.org statements to broad categories of reuse: Free Re-use (public domain or attribution required), Limited Re-use (educational or nonprofit use allowed and contractual/legal restrictions), and No Re-use (in copyright or copyright not evaluated). Meanwhile, in the U.S., the controlled RightsStatements.org values are gaining traction. As they are adopted and implemented by different libraries, a critical mass of content is building in the form of digital objects labeled with a RightsStatements.org statement. Assuming implementations of the RightsStatements.org statements are generally accurate, these may soon be incorporated into existing searches and into digital library interfaces to allow search by reuse. The interface on Europeana shows the kind of application that is possible with widespread adoption of the rights statements as digital library technologies begin to incorporate this information into the interfaces.

Background on FLVC/FALSC Hosting for Digital Library Content

The Florida Virtual Campus (FLVC) and Florida Academic Library Services Cooperative (FALSC) are state-established governmental entities in Florida.[9] FALSC is housed within FLVC. FALSC provides centralized technology-based services to all main campus libraries in public higher education in Florida: the Florida State University System and Florida State College System. At this time, this represents 40 institutions total.

Participation in the centralized online catalog is mandatory. Access to digital library hosting services is optional and is provided free-of-charge. As of summer 2019, 21 institutions use digital library hosting services through FALSC’s Islandora platform to publish open access content to the web. Not all have a public web presence. Some do not maintain their own public web presence, but rather display materials through a Publication of Archival Library & Museum Materials (PALMM) site where materials from several digital libraries around the state are grouped into collections around Floridiana topics and are displayed together, with institutional branding appearing on individual items in the bigger digital library.[10] PALMM is a long running collaborative project which launched around 2000 based on collaborative digitization efforts begun in 1998.[11] PALMM contains materials related to Floridiana, unique collections held by institutions in Florida, and collaborative collections where materials are held across multiple institutions and are presented together on the shared site to present a unified whole.

In 2014 and 2015, FALSC was restructured from two predecessor organizations, the College Center for Library Automation (CCLA) and the Florida Center for Library Automation (FCLA). FCLA had previously provided digital library hosting services since at least 1994, with the Florida Entomologist journal coming online hosted by FCLA prior to 1994.[12] As a result of such a long history of digital library hosting, institutions using FALSC’s digital library services have a significant amount of material hosted on FALSC’s servers which were uploaded long before the RightsStatements.org standard existed. These historic materials had metadata which predated standardized copyright statements and required metadata remediation to add statements.

Background on the SSDN and DPLA in Florida

The DPLA provides a centralized search of digital library resources. The DPLA launched in 2013 after a two and half year planning and design phase. It contains records for more than 21 million items coming from more than 3,000 cultural heritage institutions around the United States.[13]

The Sunshine State Digital Network (SSDN) is Florida’s DPLA hub.[14] In summer 2018, the SSDN released metadata guidelines for digital libraries wishing to contribute records to the DPLA through the SSDN.[15] A copyright or license statement is required by SSDN, and a preferred format for this statement is RightsStatements.org .

Throughout 2018 and to present, there has been widespread interest in SSDN and DPLA participation among FALSC members’ digital libraries.

RightsStatements.org Implementation

Adding the standard to FALSC’s local Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS) metadata profile.

FALSC-hosted Islandora sites use MODS to store metadata. The metadata profile for the Islandora sites is posted to https://fig.wiki.flvc.org/wiki/index.php/Metadata#FLVC.27s_Local_MODS_Profile. The MODS profile is used for internal software development and promoted to librarians working with metadata around the state as a way to check over internal workflows and verify that the use of MODS is consistent with FALSC tools and software. After the SSDN released metadata guidelines in summer of 2018, FALSC promptly checked over the guidelines and ensured that each standard could be met by member libraries wishing to participate in SSDN and DPLA.

Initial analysis revealed copyright statements as a key field to focus on. The copyright statement was the only field required by SSDN which was not previously required by FALSC’s MODS profile or by the software implementation of the FALSC Islandora platform. Accordingly, FALSC coordinated with member libraries using the Islandora platform and proceeded to implement RightsStatements.org in the Islandora platform.

Adding the Rights Statements to the FALSC MODS profile.

FALSC’s MODS profile lists a handful of extra requirements beyond the Library of Congress’s MODS standard. Additional requirements generally are in place because of software requirements.

Based on an analysis of Solr and XPATH used in FALSC’s MODS editing forms, FALSC determined to store the Rights Statements as follows:

Example RightsStatements.org element in a MODS record:

<accessCondition type="use and reproduction" displayLabel="RightsStatements.org">

http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/

</accessCondition>

Example Creative Commons element in a MODS record:

<accessCondition type="use and reproduction" displayLabel="Creative Commons">

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

</accessCondition>

The displayLabel attribute is available for any MODS element and provides an easy way to isolate the RightsStatements.org controlled values in a record. It is more reliable than string matching, and so allows code and XPATH queries to accurately isolate and manipulate the RightsStatements.org values.

Configuring Solr such that the search results can be meaningfully faceted by reuse rights.

Libraries using the FALSC-hosted Islandora perform an advisory role for the service. Any libraries eligible for services through FALSC are welcome to participate in monthly meetings of the Islandora SubGroup (ISG) of FALSC. The ISG considers issues that affect all sites, such as standardized settings which are configured centrally by FALSC (standardized settings in the software allow FALSC to provide meaningful training and troubleshooting to many campuses), prioritizing software development, and identifying issues which affect all sites.

Following SSDN’s release of metadata guidelines, the RightsStatements.org values were discussed at the monthly ISG meeting. There was widespread interest among member libraries in implementing the statements. Two main concerns came out of ISG meetings. One aspect of discussions was how to represent the RightsStatements.org values in the user interface for researchers and members of the public using the Islandora sites. The other was a concern from the ISG with how to add the RightsStatements.org values to a large backlog of materials.

The ISG quickly determined that faceted search and search options built on the RightsStatements.org values were desirable. In a search interface, a large number of options can be confusing and difficult for researchers to understand. The ISG quickly determined that it would be desirable to show fewer than 12 options to end users. A good model for how reuse might appear in search came in the form of Google Advanced Search, which uses the long standing and well-established Creative Commons licenses to allow search by “usage rights”.The key concept desired by ISG was to have many statements grouped into a smaller number of easily understandable categories.

A smaller group was formed within the ISG, In order to determine how to group the RightsStatements.org values into broader categories. This group was formed from any interested librarians who responded to a recruitment call at the ISG meeting and through the ISG’s listserv. Additionally, FALSC reached out to scholarly communications librarians at member institutions and requested input on how to represent the RightStatements.org values to researchers and the public. Through a series of meetings and emails, the group considered different categories to break the statements into.

Possible sources for facets.

The ISG considered several possible breakdowns of RightsStatements.org values into a smaller number of easily understood and easily managed categories.

Google Advanced Search: Restricting search by reuse rights.

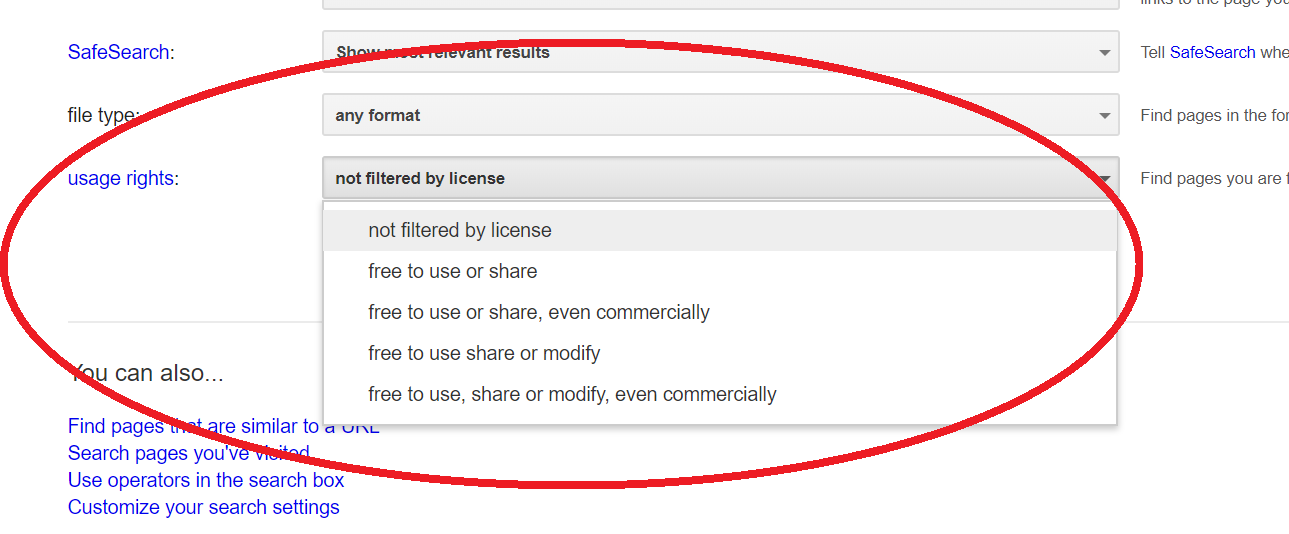

Google Advanced Search was one possible source for categories of reuse rights. The search options in Google Advanced Search use the well established Creative Commons licenses to allow searchers to filter by 5 possible reuse rights: “not filtered by license”, “free to use or share”, “free to use or share, even commercially”, “free to use share or modify”, and “free to use, share or modify, even commercially”.

Figure 1. Screenshot of how Creative Commons licenses are used for searching by category of reuse in Google Advanced Search.

RightsStatements.org : The Rights Statements are grouped into three reuse categories.

The 12 RightsStatements.org values are listed below. On the RightsStatements.org website, the statements are broadly grouped into three categories: In Copyright, No Copyright, and Other.[16] These three categories were considered as a possible grouping for the Florida system.

Table 1. The Rights Statements as grouped on the https://rightsstatements.org website.

| Rights statements for in copyright objects | |

|---|---|

| In Copyright | URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ |

| In Copyright – EU Orphan Work | URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC-OW-EU/1.0/ |

| In Copyright – Educational Use Permitted | URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC-EDU/1.0/ |

| In Copyright – Non-Commercial Use Permitted | URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC-NC/1.0/ |

| In Copyright – Rights-holder(s) Unlocatable or Unidentifiable | URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC-RUU/1.0/ |

| Rights statements for objects that are not in copyright | |

| No Copyright – Contractual Restrictions | URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/NoC-CR/1.0/ |

| No Copyright – Non-Commercial Use Only | URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/NoC-NC/1.0/ |

| No Copyright – Other Known Legal Restrictions | URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/NoC-OKLR/1.0/ |

| No Copyright – United States | URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/NoC-US/1.0/ |

| Other rights statements | |

| Copyright Not Evaluated | URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/CNE/1.0/ |

| Copyright Undetermined | URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/UND/1.0/ |

| No Known Copyright | URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/NKC/1.0/ |

Europeana: The Rights Statements are used for faceting search results into three broad categories.

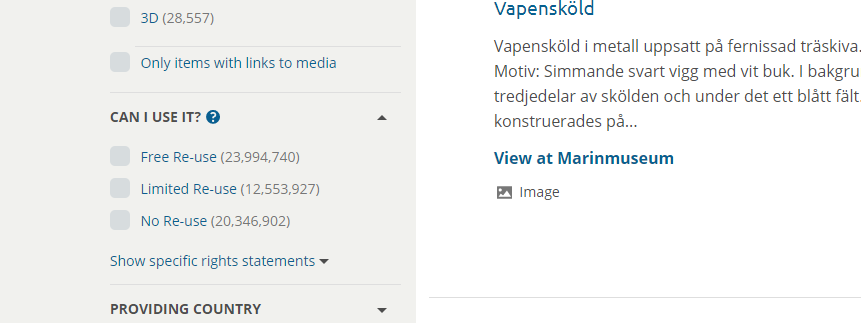

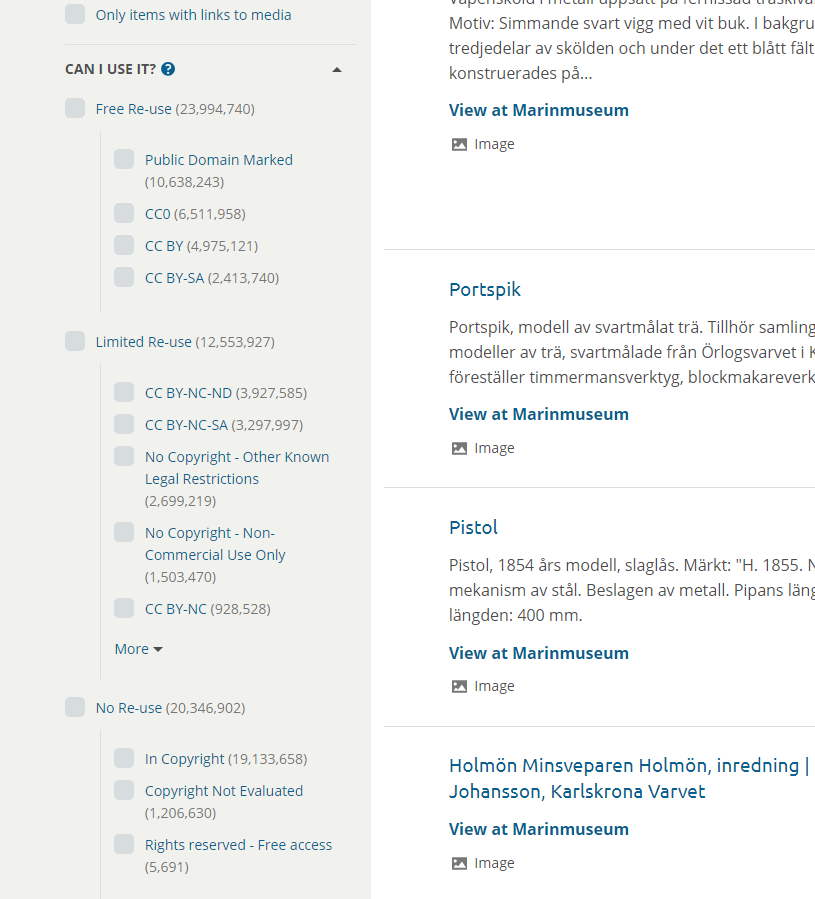

Europeana incorporates the Rights Statements into its search interface in the form of facets on the left hand side of search results.

Figure 2. Reuse categories powered by RightsStatements.org on the Europeana search interface. The facets appear on the left hand side of search results.

Figure 3. Screenshot of the expanded facets in the Europeana search interface, showing which RightsStatements.org value is grouped into which category.

Florida’s decision to follow Europeana.

After several meetings of the subcommittee within ISG, the group came to the consensus to follow Europeana. The reasoning behind this is that Europeana was the only identified user interface built on RightsStatements.org, and the Florida systems wished to follow that example on the theory that DPLA and other large digital libraries likely will follow Europeana and that the implementation and user interface would be more standard.

A major concern expressed with Europeana’s breakdown of Rights Statements into categories is that some statuses appear to be sorted to the wrong category. For example, Europeana groups the Creative Commons (remember Creative Commons licenses are incorporated into the RightsStatements.org standard) license for Attribution-ShareAlike into the category of “Free Re-use”. But, ShareAlike requires content that reuses or remixes an item to attach an identical license.[17] That’s a significant restriction because someone cannot take material released under a ShareAlike license, rework it, and then release it freely to the public. Instead, the identical license must attach. The exact license which must be used for derivative works and remixes is dictated by a ShareAlike license. Despite minor disagreements with how the Rights Statements were sorted by Europeana, the ISG decided to follow Europeana in the interests of standardization.

Following the decision by the ISG, Solr fields were configured to allow faceting search results by the three broader reuse categories. The facets were added to logged in views for librarians around the state for preview and experimentation but were not immediately added to the public interface. Each digital library is able to send a request at any time to make the fields available to the public. Libraries which have chosen to do so have added the statements to a critical mass of items on the site before incorporating them into the public interface.

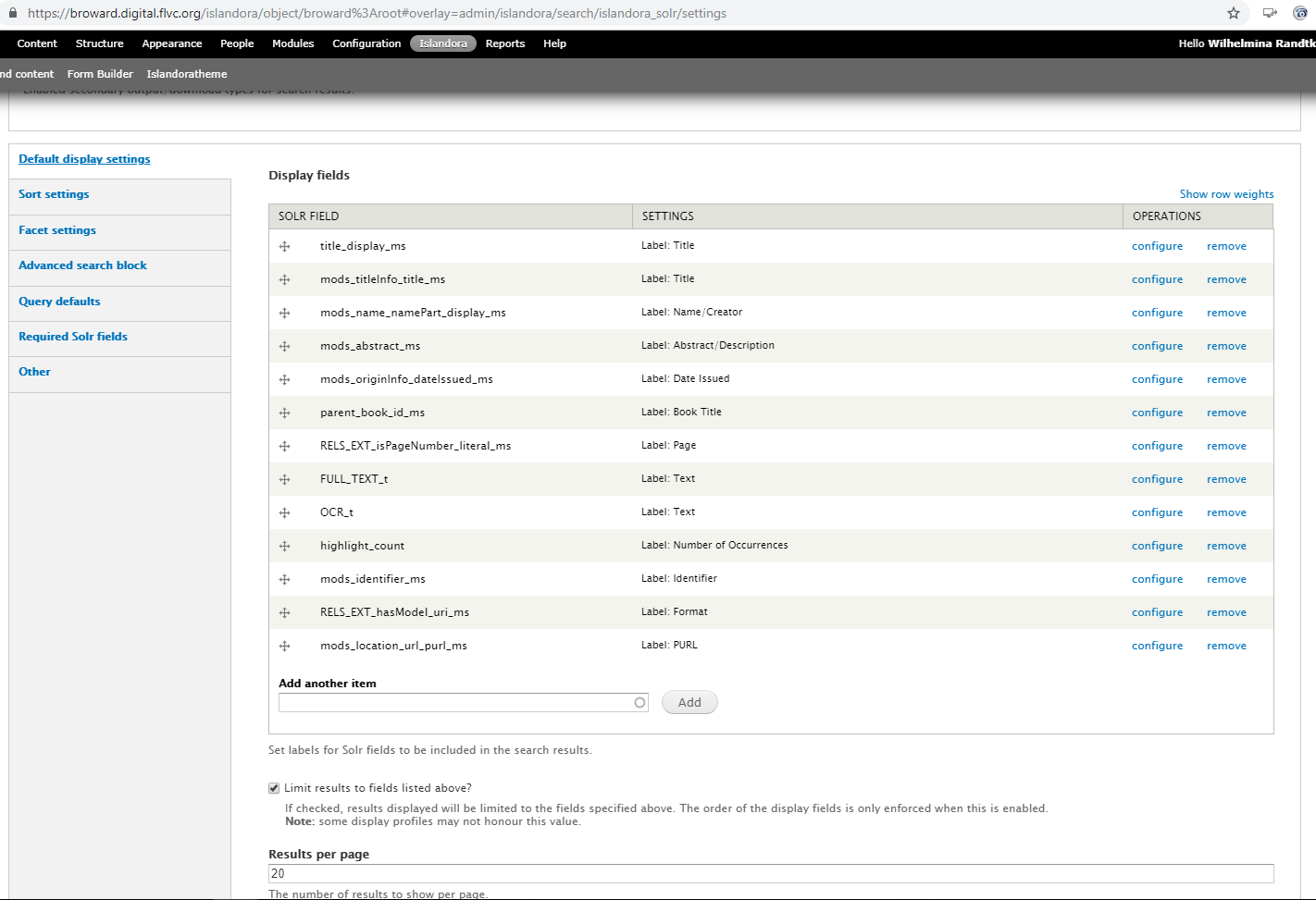

Timing and sequencing concerns in implementation: Faceted values stored directly to Solr, rather than generated on the fly from RightsStatements.org values.

In parallel with the ISG committee, FLVC has an internal FLVC Islandora Developers team which meets weekly. This team consists of computer programmers, librarians, and systems administrators who support the Islandora platform. Once the ISG had settled on the idea of breaking out the 12 Rights Statements into a smaller number of categories for search, the FLVC Islandora Developers team looked at how to implement this with Solr. Solr drives the search interface on the Islandora platform. How information is stored to Solr and which fields exist is set up by configuring Solr directly and making changes to the Solr schema. The administrative settings in the Islandora web interface allow existing Solr fields and the content indexed into them to be added to the search interface.

Figure 4. Screenshot of Solr admin settings on Broward College’s Islandora site. Once a field is added to Solr’s indexing, and that field has been populated, it’s easy and straightforward to incorporate that field into the user interface for Islandora.

Each item in Islandora is indexed into Solr when the item is initially created and the Solr index is updated each time the item’s metadata is updated. Comprehensively reindexing the sites is no small task. As of summer 2019, there are approximately 200,000 MODS XML records indexed to Solr across the Islandora sites for the 21 institutions using Islandora. Comprehensive reindexing of Solr would require significant time, measured in days, and would have an impact on the Florida Islandora system performance. The reason for this is that there are many items stored in the system with full text included, so there’s more to index than just MODS metadata fields. The full text records are voluminous and require more time per record than would MODS metadata only. Selectively reindexing items with a specific metadata field would require directly accessing and analyzing the MODS XML records in order to pull a list of items to reindex. Doing so would be manageable but would have been an extra step. Comprehensive reindexing in smaller chunks also involves an extra level of choreography. In short, in implementing a new field, it was desirable to avoid reindexing.

The way to avoid reindexing is to configure the Solr schema for a new field before adding that field to records. Therefore, no RightsStatements.org values were added to records until both the ISG had made recommendations regarding fields and the changes had been implemented in the Solr configuration. Following the SSDN’s release of metadata guidelines in summer 2018, the process of determining how RightsStatements.org would be incorporated into the user interface and implementing that decision in Solr was completed approximately 4 months later, in mid-Fall 2018. Following that, updated MODS metadata editing forms were released to libraries to allow the RightsStatements.org values to be added to records.

Adding the RightsStatements.org values to metadata forms available to librarians and others adding material to the Islandora platform.

The Islandora software handles metadata entry and updates using the Islandora Forms Module.[18] Librarians using FALSC-hosted Islandora can update metadata on records by clicking to one of two standardized forms used across all Islandora sites in the FALSC system and maintained centrally by FALSC. Unless FALSC makes a separate process available focused on a specific field, there is no way to do a batch update of metadata across a site or collection.

Adding RightsStatements.org values to the MODS editing forms did not present a streamlined path forward for digital libraries wishing to add statements to a large backlog of materials, collected and hosted beginning in the 1990s decades before the standard existed. Adding the statement manually to a single record takes 8 clicks. While that can be streamlined somewhat with a direct URL to open the metadata form for an object, comprehensive implementation using only the Islandora MODS forms would have involved a lot of clicking.

Assisting Member Libraries in Implementing the RightsStatements.org Values with Reports of Digital Library Objects and a Batch Insert.

FALSC supported Rights Statements implementations at member libraries by sharing existing training resources from other groups regarding RightsStatements.org and copyright, by providing Excel spreadsheet reports of digital library metadata to assist libraries in quickly working through materials, and by coding a batch insert to allow libraries to return a completed Excel spreadsheet and have FALSC batch add the values to existing Islandora materials.

Sharing training materials about the copyright statements.

Because librarians working with the Islandora platform come from a wide variety of backgrounds and often wear many hats on their campus, FALSC’s goal was to point to concise training materials. FALSC selected a small set of educational materials which were concise and could be worked through in less than a day. The following three resources were promoted to libraries as good starting points for gaining the educational background needed to implement RightsStatements.org :

- ASERL webinar about RightsStatements.org[19]: An excellent one hour introduction to RightsStatements.org It is a good resource for determining how to approach RightsStatements.org and deciding whether to implement the statements in a set of digital library materials.

- Society for American Archivists’s (SAA’s) Guide to Implementing Rights Statements from RightsStatements.org[20]: Only 7 pages long with a flow chart. This is a great place to start for planning workflows for assigning RightsStatements.org values to items in a digital library. Because it is short, it is easy to provide to anyone at a library who will work with implementing the statements.

- Cornell’s copyright status chart: Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States[21]: A long chart (14 pages if copy-pasted into MicroSoft Word) for pinpointing the copyright status of an item that isn’t in one of the clear categories mapped out in the SAA guide. This is a good reference for digging into the copyright status of a single book or item.

Additionally, libraries were able to meet up with FALSC online through screen sharing and go over reports, collections, and the RightsStatements.org materials.

Reports of all materials on each Islandora site.

Shortly after SSDN released metadata guidelines and as part of the early discussions about copyright at the ISG, FALSC prepared reports of items on the Islandora sites with the goal of providing information that could help libraries to determine copyright status.

The reports included for each item on the site with a MODS record:

- Identifier of item

- Link to the item on the digital library

- Islandora Content Model of item (ie. Book, PDF, Basic Image). Taken from the Islandora Content Model, which is a software setting that describes what components a digital object has and how to display that item in the web interface. It is not taken from the MODS metadata.

- Collection the item was in. This allowed quickly sorting and marking the same status for homogenous collections.

- Title

- Any date information. Because MODS has several fields where a publication date can be stored, these fields were concatenated. (ie. The elements <dateIssued>, <dateCreated>, <dateCaptured>, <copyrightDate>, and <dateOther> were all provided together in a single column of an Excel report.)

- Any existing copyright statements. (ie. contents of either <accessCondition> with no type attribute or of <accessCondition type=”use and reproduction”> element)

- A blank area to add a RightsStatements.org value.

Reports were provided to the primary contact for each Islandora implementation in an Excel spreadsheet.

Islandora plays a varying role from campus to campus across the state. Some campuses have daily activity with multiple full-time librarians working on the Islandora platform. Others have content hosted but are not actively adding content and do not regularly attend ISG. Because of this, FALSC made sure to reach each recipient of the report by phone before sending a report. The phone call allowed FALSC to explain that adding the RightsStatements.org values was voluntary so the spreadsheet did not have to be completed and that FALSC was focusing on this field because of widespread interest among ISG members in SSDN and DPLA participation. Initial phone contact was important so that libraries without staffing or desire to add the statements would not misunderstand why they were getting a spreadsheet. Phone contact also ensured that each library would be aware that applying to the SSDN and DPLA was a separate additional process and not mediated by FALSC.

Along with the spreadsheet reports, FALSC suggested to libraries that if a critical mass of reports were returned, and if multiple libraries across the state requested a batch insert, that coding the insert might be possible. Libraries were encouraged to hold off by manually adding the statement until Spring 2019, when the ISG and FALSC could be certain whether there was enough interest in the batch insert to justify the resources needed to code and implement a batch insert.

Batch insert of RightsStatements.org values.

Initial training materials and spreadsheet reports regarding RightsStatements.org were provided to member libraries in August 2018. User interface decisions and implementation in Solr were completed by November 2018. As of December 2018, three member libraries had returned completed spreadsheets with a formal request as to whether FALSC could do a batch insert, and one member library had manually implemented RightsStatements.org values comprehensively across the site using the MODS forms. Multiple requests for a batch insert and the fact that other libraries had indicated a future intent to return the reports justified allocating resources for the batch insert.

In early 2019, work to code and promote the batch insert began. FALSC provided specs to FLVC’s Division of Information Technology unit and code was available in February 2019. Code was not available to member libraries and instead the insert is run by FALSC librarians in command line. The batch insert script takes a .csv file as input with a list of identifiers and corresponding RightsStatements.org values. Islandora 7, currently in use at FLVC/FALSC, is built on a Fedora Commons 3.7.1 framework and stores metadata as MODS XML text files. The script goes row-by-row and inserts the value directly into MODS XML then trips off Solr reindexing for that item.

During February and March 2019, FALSC promoted the batch insert. The ISG and individual libraries were contacted and informed that any libraries returning a completed or partially completed report would be able to have the batch insert done. On contact, several libraries returned completed spreadsheets which the libraries had prepared in Fall 2018 but not yet submitted. Updated reports including newly added materials were available on request.

Libraries expressing a need for further training in copyright were offered screen sharing sessions where FALSC and the library worked through reports and identified RightsStatements.org values for specific categories of materials, such as public domain for materials published in the United States before 1924, educational use only for specific collections of homogenous materials, or in copyright for newer materials such as current campus publications. The screen sharing sessions focused on large chunks of content similar to those in the flowchart in the SAA guide. Some of the focus of screen sharing sessions was also on how to better group similar content in Excel in order to more efficiently fill out the spreadsheet.

When a library returned a completed report, FALSC would check over the report at a high level. FALSC checked formatting of the RightsStatements.org URIs, and any irregularities were automatically corrected. If a library typed out words for a statement, for example, “in copyright” rather than providing the RightsStatements.org URI, a URI was suggested and the library was contacted to approve the URI. If a library turned in less meaningful values, for example, “Copyright Not Evaluated” for all items, the library was asked to confirm before running the insert. On follow up, no member library opted to globally apply “Copyright Not Evaluated.” For any inserts that looked inaccurate, FALSC asked the library to confirm before running the insert. For example, a follow up question might be asked about very old materials marked as in copyright. Most returned spreadsheets of values for insert were generally accurate. Most libraries that were offered to meet up and review items together accepted the invitation.

By the end of March 2019 the batch insert had been run to add RightsStatements.org values to 35,477 items on the Islandora sites. This represented 62% of the public items across the Islandora sites not coming through FSU and more than 80% of PALMM Islandora materials. FSU has an in-house metadata librarian who is able to use XSLT to make batch inserts. FSU’s local MODS profile differs slightly from FALSC’s, including an implementation of RightsStatements.org values in MODS. Regarding FSU, FALSC coordinated to ensure compatible Solr indexing, but did not assist with the batch insert. Only 52 of the 35,477 inserted RightsStatements.org values were for “Copyright Not Evaluated” and the added RightsStatements.org values represent meaningful information for search. Libraries not participating in the batch insert cited primarily staffing as the concern.

Some background on what records are shared may be helpful in understanding the scale of the content. In terms of numbers of items across the Florida Islandora system, the Florida Islandora sites are configured to share out by OAI-PMH only top level records for newspapers and serials, but to not share out issue and article records. So, in the case of a newspaper, a single record can represent thousands of individual issues made available through the software.

Going forward, FALSC offers the ability to batch insert RightsStatement.org values. Since March 2019, a trickle of requests has come in for batch inserts and FALSC anticipates promoting the batch insert on a regular basis.

RightsStatements.org in the Islandora user interface

For sites which have requested to make the reuse facets available in search, the facets for reuse show up along the left hand side of search results under the heading “Can I Use It? Rights Status”. This mirrors the language used on Europeana, and the breakdown of which statements map to which facet also mirrors Europeana. The final groupings of Rights Statements and Creative Commons licenses into categories for faceting are shown below in Table 2.

As of summer 2019, facets can be seen on the digital libraries for the PALMM project[22], Broward College[23], and Florida Gulf Coast University[24].

Table 2. Groupings of RightsStatements.org and Creative Commons licenses into broader reuse categories on the FALSC Islandora sites.

| Free Re-use |

|

| Limited Re-use |

|

| No Re-use |

|

Figure 5. Facets on the PALMM Islandora search appearing to the left of search results.

Recommendations for others implementing RightsStatements.org

In providing reports to libraries, the fields chosen (identifier of item, link to item on the digital library, Islandora Content Model, collection the item was in, title, all date information, and existing copyright statements) were useful for quickly determining copyright status for many materials and for being able to click into items in the digital library for a closer look.

One weakness in the reports was that the collection information was not emphasized. In fielding follow up questions, it became clear that sorting out by collection and determining status one collection at a time was the best strategy for quickly and accurately working through digital library materials at many institutions. It is recommended that any digital libraries looking to implement the RightsStatements.org values first examine copyright status at a collection-level and only go at an item-level when a collection contains a variety of widely varying content. This collection-level strategy should be emphasized early in any comprehensive implementation of the Rights Statements.

Running the batch insert centrally rather than providing it as a self-service tool was also desirable because the few formatting issues with the RightsStatements.org values returned by libraries could be corrected. For example, formatting issues included https instead of http for a URI and a copied and pasted URL for a webpage showing the text of the statement instead of the URI. By fixing basic formatting centrally, some frustration was likely avoided across the state and it ensured that well-formatted data went into the system. The batch insert code validates against the list of RightsStatements.org URIs. By running the batch insert in-house, FALSC reviewed error reports and centrally corrected formatting issues. Running the batch insert centrally was also desirable for being able to push out copyright training and information about the SSDN and DPLA. In promoting the insert, FALSC was able to field basic questions and to connect libraries with information and resources as needed.

A major shortcoming of the batch insert is that FALSC only inserted the controlled RightsStatements.org values and did not simultaneously insert an uncontrolled copyright statement showing the logic behind that copyright status determination. In looking at a metadata record, seeing a status of “no copyright US” is not quite as good as seeing that in combination with an uncontrolled statement like “Published in the US before 1978 without a copyright notice. Not subject to US copyright.” Currently, in Florida Islandora sites, there’s no way for the library to “show the work” behind the copyright determination without manually going in and adding the uncontrolled statement. In asking questions about returned spreadsheets and in screen sharing meetings with libraries to go over materials, it is clear that libraries put thought and care into the copyright status determinations. For example, libraries marking very old materials as “in copyright” tended to do so because the digital library interpreted that specific digital image made by the campus to be under copyright, although the original digitized item was not. Another example is libraries working with a collection where the donor had pledged certain rights with the donation may have an accurate RightsStatements.org value with respect to reuse rights, but without the uncontrolled statement, it’s not possible to confirm that purely by looking at the item and its metadata online. In many cases, the same RightsStatements.org value was applied across material in an entire collection. It would have been straightforward to simultaneously document the decision making process had code been planned, spec’d, and written to support that documentation in the form of allowing the library to batch insert an uncontrolled copyright statement along with the RightsStatements.org value. It is strongly recommended that any project to comprehensively add RightsStatements.org values also simultaneously allow adding an uncontrolled statement to “show the work” and demonstrate the logic behind the copyright statement.

A significant weakness in the FALSC implementation is that copyright training was offered later rather than earlier in the project. Staffing is a big concern with a consortium supporting many institutions. In any consortial implementation, a good path to follow might be to recruit potential peer mentors around the state and locate librarians with backgrounds in copyright who are able to answer questions and work through items and collections with librarians whose strengths are in other areas. This is also something for DPLA hubs to consider in an implementation. Experience with copyright was highly variable among librarians across the state and mentoring, or even the ability to get a quick answer to a question, was often not available within a given member library. Community networks, specifically for assistance with determining copyright status, could be helpful.

It’s also important to stress that the RightsStatements.org values are specifically written to avoid liability, so adding them to materials does not trigger legal issues. Something like release forms should always be sent for review within a campus or organization, but basic education and mentoring in determining status should not normally require legal review. The RightsStatements.org values are written specifically to avoid that need.

References

[1] See, for example, the rights statement language for “No Copyright – United States” at http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/NoC-US/1.0/. The notices section states, “Unless expressly stated otherwise, the organization that has made this Item available makes no warranties about the Item and cannot guarantee the accuracy of this Rights Statement. You are responsible for your own use.” A standard disclaimer included on all rights statements states, “DISCLAIMER The purpose of this statement is to help the public understand how this Item may be used. When there is a (non-standard) License or contract that governs re-use of the associated Item, this statement only summarizes the effects of some of its terms. It is not a License, and should not be used to license your Work. To license your own Work, use a License offered at https://creativecommons.org/“

[2] https://creativecommons.org/.

[3] https://www.google.com/advanced_search.

[4] https://www.europeana.eu/portal/en.

[5] History [Internet]. [updated 2011 April 28]. Mountain View (CA): Creative Commons; [cited 2019 June 7]. Available from https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/history

[6] Fallon J, Senior Policy Advisor, Europeana Foundation. 2016 April 14. Rightsstatements.org launches at DPLAfest 2016 in Washington DC. Europeana Pro. Available from https://pro.europeana.eu/post/rightsstatements-org-launches-at-dpla-fest-in-washington-dc

[7] Europeana Foundation. 2015 Feb 1. Archives Europeana Rights Statements – for reference only. The Hague (Netherlands): Europeana Foundation; [cited 2019 June 7]. Available from https://pro.europeana.eu/files/Europeana_Professional/IPR/archivedrightsstatementspages-2.pdf

[8] For many searches, a large number of hits locate items with a Copyright Not Evaluated status. For example, as of July 2019, searching the word “language” on Europeana’s search portal homepage at https://www.europeana.eu/portal/enresults in 274,594 hits. Facets show that 118,094 of these have a rights status of “Copyright Not Evaluated”. Regarding overall coverage, an empty search of Europeana results in 57,714,214 hits. Facets show that 1,207,685 of these have a status of “Copyright Not Evaluated”.

[9] Florida Statutes section 1006.73 (2018). Available from http://www.leg.state.fl.us/statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&Search_String=&URL=1000-1099/1006/Sections/1006.73.html.

[10] http://palmm.digital.flvc.org.

[11] Henjum, E. Introducing the Florida Heritage Collection: A Cooperative Digital Library Initiative. Florida Libraries 2000 Fall; 43:8.

[12] Clement GP. 1994. Evolution of a Species: Science Journals Published on the Internet. Database 17:44-46.

[13] Gore E. 2018 April 18. DPLA: A Look Back on the Last 5 Years. Boston (MA): Digital Public Library of America; [cited 2019 June 7]. Available from https://dp.la/news/dpla-a-look-back-on-the-last-5-years

[14] https://sunshinestatedigitalnetwork.wordpress.com/.

[15] Sunshine State Digital Network Metadata Working Group. SSDN Metadata Participation Guidelines Version 1. Sunshine State Digital Network; 2018 July 1 [cited 2019 June 7]. Available from https://docs.google.com/document/d/1wmjl8tBf3-oa3X8asPGPNhdCeGGM7PPVy2Xu9RxJpHU/edit

[16] https://rightsstatements.org/page/1.0/?language=en

[17] See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode and https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/licensing-considerations/compatible-licenses .

[18] How to Edit/Create Ingest Forms. [updated 2019 April 16]. Charlottetown (PE, Canada): Islandora Foundation; [cited 2019 June 7]. Available from https://wiki.duraspace.org/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=69833497

[19] Gore E, Hansen D. 2016 Dec 1. ASERL Webinar: “Overview of RightsStatements.org” [videorecording]. Atlanta (GA): Association of Southeastern Research Libraries; [cited 2019 June 7]. Available from https://vimeo.com/193942186

[20] SAA Intellectual Property Working Group. Society of American Archivists Guide to Implementing Rights Statements from RightsStatements.org. Society of American Archivists; 2016 Dec [cited 2019 June 7]. Available from https://www2.archivists.org/sites/all/files/RightsStatements_IPWG%20Guidance.pdf

[21] Hirtle, P. Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States [Internet]. [updated 2019 Feb 7] Ithaca (NY): Cornell University; [cited 2019 June 7]. Available from https://copyright.cornell.edu/publicdomain

[22] https://palmm.digital.flvc.org. The PALMM Islandora site includes contributions from University of West Florida, Florida Gulf Coast University, University of Florida, University of Central Florida, University of South Florida, Florida State University, Florida International University, Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, University of North Florida, Florida Atlantic University, and Indian River State College.

[23] https://broward.digital.flvc.org.

[24] https://fgcu.digital.flvc.org

About the Authors

Wilhelmina Randtke is the Digital Library Services and Open Educational Resources Coordinator at the Florida Virtual Campus’s Florida Academic Library Services Cooperative. At the consortium, she supports digital publishing and digital library activities at member libraries across Florida through training, technical support, facilitating connections between campuses, and assisting in prioritizing and routing issues for attention by technologists.

Randy Fischer is Software Applications Engineer in the Florida Virtual Campus’s Division of Information Technology. He supports the Islandora digital library platform through maintaining code to streamline batch ingests of content to the Florida Islandora sites, and streamlining processes at scale in the Islandora digital library platform.

Gail Lewis is Web Applications Engineer in the Florida Virtual Campus’s Division of Information Technology. She supports a variety of Solr applications at the consortium including configuring Solr and monitoring indexing issues for Islandora and in the statewide discovery tool, Mango. She maintains the Table of Contents display functionality in the Islandora book module and maintains the Islandora IP Embargo module.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply