by Julie Burns, Laura Farley, Siobhan C. Hagan, Paul Kelly, and Lisa Warwick

Introduction

On Friday, March 13, 2020, the Executive Office of the Mayor Muriel Bowser sent an email to all government employees announcing DC Public Schools and DC Public Library locations would be closed until Wednesday, April 1 in response to the increasing spread of COVID-19 within the region. On March 30, with New York City under a strict lockdown, Mayor Bowser announced a stay-at-Home order for the District of Columbia. The opening date for DC Public Library was ultimately pushed back to May 29, when select library branches started providing curbside services.

The People’s Archive is the local history center for the DC Public Library. The first week working from home, the People’s Archive Manager, Kerrie Cotten Williams, asked how the department could document this moment in history. The same way we were looking back on the pandemic of 1918, future generations would be asking what it was like to be alive during this time. We felt a responsibility to collect from and connect with our community.

Our first step was to gather information on what other organizations had already started in this vein. The DC History Center encouraged people to start diaries with the intention of donation [1] . The Arlington Public Library collected homemade zines[2]. There were also national projects collecting firsthand accounts.

The People’s Archive’s mission is: “to connect you to unique resources that illustrate the District of Columbia’s local history and culture. We are a home of discovery, where diverse stories – past and present – are preserved and amplified.” Our department had been rebranding over the course of the last year with increasing emphasis on documenting the everyday experience of life in the District; not just the story of those in power. Along with informing the public, creating community and connection was also considered. Our department wanted a participatory campaign that would be: easy to collect and share; create a sense of community; and serve as a vehicle to talk about history in daily life.

After creating a rough outline of our concept, we reached out to our staff to form a committee to work on the project. Having a small group allowed us to be nimble and make quick decisions. This is also the group that made selection decisions and created metadata later in the project. Our team included: Julie Burns, Library Associate; Laura Farley, Digital Curation Librarian; Siobhan Hagan, Memory Lab Network Project Manager; Paul Kelly, Digital Initiatives Coordinator; Maya Thompson, Library Associate, and Lisa Warwick, Reference Coordinator. With our team assembled, we began the work of building Archive This Moment D.C. (ATMDC).

Staff chose to collect via social media using the general hashtag #archivethismomentdc so the project could be ongoing, capturing future historic moments in D.C. outside of the pandemic. This hashtag clearly stated the project goal without being specific to any event. We did not use COVID-19 or coronavirus in the hashtag or any marketing materials for this project. In an effort to limit misinformation, the District of Columbia’s Joint Information Center had to review any media from the D.C. government related to Coronavirus (COVID-19). DC Public Library’s Communications Department and the District Joint Information Center advised using the phrase: “in this time of social distancing” in our social media and marketing materials.

Another consideration was making contributing content to the project as equitable as possible. For those without social media, we created an Airtable form that could be filled out for submissions [3]. Airtable is a free, collaborative, online database and spreadsheet tool. The public was able to fill out a simple form, view and agree to usage terms, and upload files that were fed into a spreadsheet that staff could access.Some of the more varied and creative submissions came through the Airtable form or were sent over email.

It has to be emphasized that we did not know or predict that we would still be in what D.C. calls Phase 2 (limited restaurant seating, no in-person public schools, limited public transportation) nearly one year later. The urgency of the initial two, and later six week, stay-at-Home order is partially what led us to collect images, video, and text files instead of daily diaries or other ephemera, as well as using social media as the main collecting point.

Outreach and Engagement

DC Public Library took several interdepartmental actions in order to engage the community and to encourage participation in the ATMDC project. First, the People’s Archive consulted with the Library’s Communications Department. The main outreach goal was then created to target social media users. A webpage for the project was created on the DC Public Library website with all the relevant information about the initiative [4].

The Communications Department promoted ATMDC in the weekly eNewsletter in mid-April that reaches more than 200,000 people, many of whom are journalists [5] . In addition, the Deputy Mayor for Education included details on the program in their newsletter to members of the D.C. Education Cluster. The People’s Archive promoted information on the project through our departmental eNewsletter, The Intelligencer, and our departmental social media accounts [6]. DC Public Library’s main social media accounts also promoted the project. The inclusion of social media as a collection option using #archivethismomentdc was planned as not only a simple way to include more D.C. residents and meet them where they were on social media, but also as an outreach tool: as people posted their submissions to the hashtag, they were promoting our initiative to their followers as well, while engaging the D.C. community in participatory archiving and the telling of their own stories.

We sent out all-staff emails about the project asking colleagues to submit content and to share, and in addition we reached out directly to staff who we knew were on Instagram and/or Twitter and asked them to contribute to model the type of content that fit into our call for submissions. In all of our outreach and anytime someone submitted an entry through the Airtable form, we implored the reader to share the initiative with their D.C.-area friends, families, and neighbors. All this coordinated outreach led to an April 16, 2020 article explaining the project in detail and asking for submissions from District residents in Washingtonian, a digital and print magazine that reaches more than a million unique readers every month [7].

When researching previous and current similar participatory archiving projects, DCPL connected with the Maryland Historical Society, now renamed the Maryland Center for History and Culture (MCHC). Initially, this connection was for resources and information sharing, and then led to MCHC planning a webinar on this topic since there were so many folks reaching out to them with questions about participatory archiving and to share lessons learned. Staff presented on the MCHC organized virtual panel, “Collecting in Crisis: Responsive Collecting in a Digital Age” on May 14, 2020 [8]. This COVID-19-focused webinar aimed to provide a rough guide for cultural institutions in collecting crowd-sourced born-digital materials. The MCHC, Virginia Museum of History & Culture, Salisbury University, and DC Public Library shared their approaches to developing, building infrastructure, and conducting outreach to create different types of responsive collecting initiatives.

As submissions started coming in, we retargeted our outreach to D.C. neighborhoods and areas where we had received little or no submissions. We sent emails to D.C. Advisory Neighborhood Commissions, neighborhood associations, and specifically reached out to library branches in neighborhoods with zero or minimal numbers of submissions. While this did assist in engaging these regions more, our submissions were still heavily skewed towards the Northwest quadrant of the District.

An unexpected result of collecting through social media was that most submissions had a lighthearted tone that is typical to these platforms. While reviewing the submissions against a backdrop of horrible news of rising rates, we became starkly aware that we were not truly capturing the whole picture of daily life. Although some posts do show the struggles of this time, most of the submissions could be around the theme of “make the best of it” – distanced wine drinking with neighbors, porch photo shoots, walks in the park, so many cherry blossom images. (Note: the Tidal Basin was eventually closed because of too many visitors to the area.)

In September of 2020, eighty-eight photos were chosen from the Instagram submissions to be the first items ingested and published into DC Public Library’s official Archive This Moment D.C. Collection [9]. The Library’s Communications Department published a press release for the launch of the collection to the public (please see Appendix I). This garnered three local news articles on the project: one on DCist [10], an article in The Washingtonian [11], and another on the local NPR affiliate station website [12].

Technical Workflow

Collecting born-digital materials from the internet is not new to DC Public Library; indeed, when the ATMDC project began, we intended to utilize tools and techniques that were already at our disposal. In short, ATMDC was initially conceived as a web archiving project that would utilize tools such as Internet Archive’s Archive-It platform and Rhizome’s (at that time) Webrecorder. While these tools can be powerful when applied to certain situations, we found our results targeting them to crawl specific social media hashtags to be dissatisfying not only in terms of data collection, but also in terms of usability. It was during this period of experimentation that we began to crystalize exactly what we hoped this project would be, at least in terms of user-experience. We concluded that, even if our crawls were perfect (which they absolutely were not), the step of replaying WARCs through, say, the Wayback Machine was simply one too many – we wanted a sense of familiarity and immediacy in the end product more in line with a traditional digital collection.

We therefore turned to the Twitter and Instagram APIs, and to George Washington University’s Social Feed Manager (SFM) [13] Twitter module and arc298’s Instagram Scraper [14]. This approach eliminated our frustrations with incomplete web crawls because we were no longer reproducing websites (we were now harvesting images and extensive descriptive and technical metadata directly), but it was not without its challenges. While SFM utilizes a relatively intuitive browser-based interface once installed, reaching that point, which requires not only deploying Docker containers but also acquiring API credentials and adding them to the program, is not exactly straightforward for new users. These API credentials were essential to performing the work, and we were lucky to already have them (indeed, we requested an additional set from Twitter when the project began and as of the date of publication the request remains unfulfilled). Instagram Scraper conversely requires no such credentials due to the more open nature of the Instagram API. In this sense, it’s easier to begin using, but is more difficult in others (it must be installed via pip, and its operation is command-line only).

The Digital Curation Librarians installed the selected programs on their personal computers, since they were on leave when the stay-at-home order took effect, rendering their work-supplied laptops inaccessible. This was a less than ideal scenario, but options at that time were frankly limited. SFM was configured to harvest both media and metadata based on a Twitter search for #archivethismomentdc once every 24 hours; Instagram Scraper was configured as a scheduled task where a command would be similarly executed every 24 hours, also harvesting media and metadata based on a search for the same hashtag. Due to harvesting problems that were never fully reckoned with, SFM was only able to collect tweet datasets, but not the associated media. Therefore, results of those harvests were retained in Docker, exported as JSON once per week, and the Twarc Python library was utilized to collect any media missed by SFM. All metadata and media collected was backed up on a work-supplied external hard drive, and in a dc.gov Google Drive that was shared with all project team members to facilitate appraisal.

Appraisal and Selection

Initially, our methods of selection were set out loosely in our call to participate (see Appendix II). We required submissions to be sent to us via certain channels, and we allowed all types of digital media. We then began to refine our selection criteria to just the geographic area of the District of Columbia and offered tips on what type of content to submit. After receiving several submissions, we began to formulate a more solid selection criteria we called our First Pass. (see Appendix II). During the collection period we received over 9,000 pieces of media. We began the selection process by splitting up the submissions amongst the group and used the criteria to come up with “yes” or “no” answers to submissions. The “maybe” submissions would be discussed by the group. In our spreadsheet of submissions, we instructed everyone to put in the notes field reasoning for a “maybe” designation. Media were typically flagged “maybe” for content including: protests; faces of children; personally identifiable information like phone numbers, addresses, or health information; or where consent was in question. The group decided it was best to confirm consent with the creator before posting content with any of these issues. It is important to note that collecting from a social media hashtag leaves more of a chance that the donor does not fully understand or know about the extent of our project, whereas with the Airtable form we created, there was a box that had to be checked to affirm consent from the donor. Perhaps an Instagram user saw their friend use the hashtag and just wanted to use it themselves, without realizing that it was part of a participatory archiving project? We regularly collect unknowingly from publicly available social media accounts in our regular web archiving collecting workflows, but we felt with this project we needed to ethically double check on consent with certain subject matter.

By the beginning of June, people began using #archivethismomentdc to document protests and marches that swept through the entire nation in response to the murder of George Floyd. Since protests were not within our initial collecting scope of ATMDC, we had to pause the project and reconsider. We began to discuss as a group if we would allow protest content to be included with our criteria–after all, this was what was happening in D.C. at the moment. Initially, we discussed potentially including it with selection criteria ensuring that we did not collect any media with people’s faces, but even this didn’t seem to be enough.

Our reticence stemmed from two issues: the fact that we had specifically set out to collect submissions about life in the District under required social distancing; and to protect the privacy and safety of protesters and activists. We had difficult discussions within our department about the desire to collect materials in real-time to preserve this moment; versus the responsibility to respect the privacy and activism of those living through history.

To help inform our thinking we turned to the work of the Blacktivists [15] and WITNESS [16]. We also consulted the Society of American Archivists’ Code of Ethics which states: “Archivists recognize that privacy is an inherent fundamental right and sanctioned by law. They establish procedures and policies to protect the interests of the donors, individuals, groups, and organizations whose public and private lives and activities are documented in archival holdings” [17]. We take this very seriously at DCPL. What if activists uploaded to our hashtag, we archived the content, and then they deleted it from Instagram, worried about their privacy, and they forgot that they submitted it using our hashtag? Also, we received media of crowds that included many people’s faces (most were masked, but still, there are other identifying characteristics): while the person who created the media and submitted them to our hashtag is consenting to themselves being archived, there is no way we can get the consent from all the other people.

It could be argued that the media was captured at a public event so there’s no need to eliminate these submissions, but it just didn’t feel like it fit within the Code of Ethics as we understood it. Were we getting the most informed consent we could in this submission format and with the resources we had with a limited staff? We asked ourselves, what about embargoing access to the collection for 20 years as an answer to our issues? The initial goal for the project was to engage our community virtually immediately since we could not do so safely in person, so this went against the initial project’s aim. Secondly, we felt strongly that we were limited in our ability to establish policies to protect the interests of our community, even and perhaps especially in the case of embargoed protest material. These are current events and activists who were arrested (or could still be) would be undergoing active trials–we have no precedence for collecting from active investigations and trials, and felt uncomfortable doing so.

We also felt like opening up our selection criteria to include this content would be a massively time-consuming addition to our already extensive project for our small staff, and the fact that we still couldn’t come up with answers where we all felt ethically comfortable left us with our decision.

Ultimately we chose to focus on the stay-at-home order, which lasted from March 16 to May 28, and not include protest content. We felt this kept the project to a manageable amount of work for our small department and decided to move some focus to supporting local activists not through collecting their content, but through doing what libraries do best: sharing information — specifically on personal archiving. Siobhan organized and held a Memory Lab Network webinar entitled, “Supporting Community Archivists: Preserving and Sharing Content Ethically” in August with Yvonne Ng from WITNESS and representatives from the XFR Collective [18]. Siobhan and Laura Farley gave a free one hour “Digital Preservation 101” virtual class in October to the public. We also regularly shared personal archiving resources on social media and our electronic newsletter, The Intelligencer.

By helping activists to preserve their personal archives safely, these records that document this historical moment will live on within the community. Perhaps we will then collect this media in 20 years for our archive, perhaps not. To best archive this moment in D.C., we feel that it wasn’t about collecting activists’ content at all: it was about sharing information with our community to assist them in preserving themselves.

Due to the large number of submissions and the unfamiliarity with the workflow, we decided to chunk the submissions into phases. The first phase began with Instagram hashtag submissions only and that had been selected as answering “Absolute Yes” to all of the questions in our Selection Criteria. We did not include Twitter submissions using our hashtag due to the low number of entries.

Metadata

Once we finished selecting which objects to include in the collection, we needed to describe them in order to provide context and make them accessible to users. DC Public Library utilizes the Dublin Core schema to describe objects. Collecting content via social media presented certain opportunities and challenges in terms of metadata. In addition to the usual fields such as title, date, and description, we wanted to be able to capture information unique to this type of project, such as hashtags and original captions. The first step in completing metadata for the objects to be included in the online collection was to transform the JSON file into a CSV file for tracking and reference. After mixed results with using Microsoft Excel and Python to open, parse, and write JSON files into CSV files, the “Convert JSON to CSV” tool provided by Data Designs Group, Inc. was utilized to convert the harvested data [19]. Preservation copies of the JSON files were retained.

The real challenge began with divvying up objects between staff for metadata creation. Multiple issues made what seemed at the onset to be a simple task of dividing work into a massively time intensive project. First, the file names generated by Instagram were not sequential, meaning that posts that included multiple objects would not automatically group together. This complication with the files names was not immediately obvious and as a result we began the selection process, without the JSON file, one file at a time in sequential order. Some objects alone were not worth keeping individually, but were worth keeping as part of a larger post when in context with its original media. In hindsight, consulting the metadata during file selection would have been best; however due to staffing time constraints and a desire to keep the project moving forward we learned this lesson the hard way. Ultimately, once the JSON file was converted into a master spreadsheet, it was heavily consulted in the selection process. Additionally, a column was added to each cataloger’s metadata spreadsheets indicating if an object was part of a set. This labor intensive process required sorting the master metadata spreadsheet alphabetically by the “Original Caption” field to find posts with multiple objects. This process was not foolproof, as many posts had identical or similar “Original Captions.” “User ID” and “Original Date” fields were also checked to ensure objects belonged together.

A second challenge with the JSON metadata for Instagram was that only the user ID for a post was provided, not the handle. This makes sense because the user ID remains the same if a user changes their handle; however, we wanted to display the handle in the metadata in addition to the user ID because people are more comfortable searching for and referencing handles than user IDs. It is possible to harvest a JSON file through the Instagram API with handles and user IDs, however this process requires an Access Token granted through Instagram and although both the Digital Curation Librarian and the Digital Initiative Coordinator applied, neither was granted one. As of publication they are, in fact, both still waiting for Access Tokens. A simple, though time consuming, solution was to enter each user ID into the Comment Picker “Find Instagram Username” search [20] and record the handle in a new column on the master spreadsheet.

A third challenge with the JSON metadata for Instagram was that the timestamp was recorded in Unix time, a format that is not human readable. A date converter formula was applied to the column containing the Unix time column before splitting off the hours:minutes:seconds portion of the timestamp and removing it from the spreadsheet. The result was a column of dates in ISO 8601 date and time format, YYYY-MM-DD (see Appendix III ). [21]

After resolving these challenges with the JSON metadata, each cataloger received a Google Sheet to record object metadata including: original date, original caption, hashtags, user ID, handle, and if the object was part of a set. Catalogers manually completed metadata for title, subject, neighborhood, address, and description for each object. The Library of Congress Thesaurus for Graphic Materials [22] served as our source for subject headings of images and the Library of Congress Subject Headings [23] for original captions. A local controlled vocabulary was utilized for D.C. neighborhoods and address information, if known. This project also prompted a staff discussion on the use of gendered pronouns in description fields. To avoid making assumptions about members of the public, we ultimately decided to utilize gender-neutral pronouns for ATMDC, unless the subject’s gender was otherwise known or documented. (As an aside, we plan to continue this policy for all digital projects going forward.)

Access

ATMDC is available in Dig DC, DC Public Library’s home for digital special collections, partially funded through the Institute of Museum and Library Services and supported by the Washington Research Library Consortium. Dig DC utilizes the open-source software Islandora, which provides a framework for digital asset management and access. Islandora is flexible in objects that can be ingested and highly customizable, built upon a base of Drupal, an open-source web content management framework; Fedora Commons, the underlying structure to a digital repository; and Solr, an open-source search platform. When combined these platforms and frameworks provide highly customizable, searchable, and ordered access to digital objects and some long-term preservation protections.

As previously discussed, metadata for Dig DC is created using the Dublin Core schema. After staff completes metadata for each individual digital file, Dublin Core is migrated into MODS to transform the metadata into a machine-readable XML schema. These metadata files are ingested together with digital files to create a digital object within a collection. Dig DC is made up of objects, which are digital files with accompanying metadata within a collection. Drupal offers modular Islandora Solution Packs that standardize the ingestion of objects and metadata for given formats such as newspapers, documents, or images. These solution packs may be used individually or combined within a collection depending on the format of digital files. All solution packs require a digital object and a MODS record. A high resolution digital file is ingested into a solution pack which then generates an access copy to speed up front end access and, if permissions are set to allow it, allows the user to download a copy of the object. [24] These objects may be entire archival collections selected for digitization, portions of archival collections selected for digitization, or born digital materials. In Dig DC, a collection is a grouping of objects that all come from the same archival collection; or a grouping of objects that come from different archival collections but share a common theme. All collections include brief description essays to provide context to the grouping of objects.

When considering how to build the ATMDC collection in Dig DC, the structure of the original social media posts were recreated as closely as possible. To achieve this grouping the Compound Object Solution Pack was utilized, which functions as a mini-collection within a larger collection, meaning objects of different formats may be combined within a Compound Object to create a package of objects. For example, an Instagram post with four images with the hashtag appears in Dig DC with all four images in one container, not as listed as individual objects (See Appendix IV). An additional consideration was how to best display captions, hashtags, and emojis from social media posts with the limitations of MODS. Normally this information would be included in a “notes” field in the MODS records, however the special characters and emojis could not be preserved in that format. Instead every caption was saved as a separate PDF document, regardless of whether the caption contained special characters and emoji or not. These PDF documents were then added to the compound object (See Appendix V). The resulting compound object, while not as user friendly as the original social media post, pairs the visual component of the original post with the textual component.

There are no access restrictions and few use restrictions on the ATMDC collection in Dig DC. Every collection and object in Dig DC includes a rights statement provided by RightsStatments.org to guide users on copyright and reuse guidelines. All objects in the ATMDC collection are in copyright, with the creator retaining rights. For objects submitted through Instagram the rights holder is displayed as the username. Users are able to download content from the collection but it is their responsibility to assess proper use of the objects.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Participatory collecting requires strong relationships with members of the community. We were able to engage some quadrants of the District more than others, despite efforts to reach out to community organizations and leaders. There is no catch-all solution to collecting social media materials from the internet. Web archiving has its advantages, as does harvesting via API, and archivists must be adept at iterating their approach when results do not meet expectations. Selection is a process that requires always expecting the unexpected. You can try to plan for it, but then you need to be ready to adapt to circumstances. Just because you can collect something, doesn’t mean you should. People’s safety in the present is more important than preserving material for the future. When it comes to creating metadata for objects harvested from social media, what seems like a straight-forward task may become complicated and time consuming due to unforeseen data formats. Our team learned the hard way to consult metadata in-tandem with object selection to ensure we were getting the entire context of an object. In providing access to the ATMCD collection in Dig DC, social media posts were recreated as faithfully as possible and original captions were saved as PDFs to capture special characters and emojis.

While collecting for ATMDC may have concluded, our work on this project is ongoing. Short-term steps include completing metadata on selected Instagram objects and ingesting them into Dig DC; and beginning the selection process of objects submitted through Airtable and email. Mid-term steps include revisiting the “maybe” media from Instagram and confirming consent with creators when minors are involved; and continued outreach on personal digital preservation and awareness-raising social media campaigns on ATMDC. Long-term steps include programming tailored around drawing connections between current collections and personal collecting.

Bibliography

[1] DC History Center In Real Time: Collecting Current Events webpage: http://www.dchistory.org/in-real-time/

[2] Arlington Public Library Quaranzine webpage: https://library.arlingtonva.us/2020/03/30/quaranzine-call-for-submissions/

[3] Archive This Moment D.C. Airtable form: https://airtable.com/shraWiNGyO42FNYGs

[4] DC Public Library Archive This Moment D.C. website: https://www.dclibrary.org/archivethismomentdc

[5] Archive This Moment D.C. announcement. Beyond Words [Internet].[cited 2020 Jan 08]. Available from: https://us2.campaign-archive.com/?u=ced1a87cc829e2107d5bc2dfc&id=61ecb4dbcc

[6] Archive This Moment D.C. announcement. The Intelligencer [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 08]. Available from: https://preview.mailerlite.com/i3n5q2

[7] Cartagena, Rosa. 2020. Help DC Public Library “Archive This Moment” With Your Zoom Screenshots, Quarantine Diaries, and More. The Washingtonian [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 08]. Available from: https://www.washingtonian.com/2020/04/16/dc-public-library-archive-this-moment-zoom-screenshots-quarantine-diaries/

[8] Maryland Center for History & Culture, Collecting in Crisis: Responsive Collecting in a Digital Age recording: https://vimeo.com/420284489

[9] Archive This Moment D.C. collection in Dig DC: https://digdc.dclibrary.org/islandora/object/dcplislandora%3A259406

[10] Blitz, Matt. 2020. A New DCPL Collection Shows What D.C.’s First Two Months Of COVID-19 Lockdown Looked Like. DCist [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 08]. Available from: https://dcist.com/story/20/09/30/dc-public-library-coronavirus-pandemic-archive-this-moment/

[11] Byck, Daniella. 2020. Do These Photos Perfectly Capture Life During Covid?. The Washingtonian [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 08]. Available from: https://www.washingtonian.com/2020/09/25/archive-this-moment-dc-public-library-photos-capture-life-during-covid-19/

[12] Blitz, Matt. 2020 D.C. Public Library Premieres Photo Exhibit Showcasing First Two Months Of The Pandemic. WAMU [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 08]. Available from: https://www.npr.org/local/305/2020/10/01/919072121/d-c-public-library-premieres-photo-exhibit-showcasing-early-months-of-the-pandemic

[13] George Washington University Social Feed Manager (SFM): https://gwu-libraries.github.io/sfm-ui/

[14] arc298 Instagram Scraper: https://github.com/arc298/instagram-scraper

[15] The Blackivists documenting protests resources: https://www.theblackivists.com

[16] WITNESS activist video archiving resources: https://archiving.witness.org

[17] SAA Core Values Statement and Code of Ethics [Internet]. [updated 2020 Aug 06] .Society of American Archivists; [cited 2020 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www2.archivists.org/statements/saa-core-values-statement-and-code-of-ethics

[18] Memory Lab Network, Supporting Community Archivists: Preserving and Sharing Content Ethically webinar: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_NX1ci-dSzc&t=81s

[19] Data Design Group, Inc. Convert JSON to CSV tool: http://convertcsv.com/json-to-csv.htm

[20] Comment Picker Find Instagram Username tool: https://commentpicker.com/instagram-username.php

[21] ISO 8601 Date and Time Format [Internet]. [updated 2020 Mar 11]. ISO – International Organization for Standards, Popular Standards; [cited 2020 Dec 08]. Available from: https://www.iso.org/iso-8601-date-and-time-format.html

[22] Library of Congress Thesaurus for Graphic Materials: https://id.loc.gov/vocabulary/graphicMaterials.html

[23] Library of Congress Subject Headings: https://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects.html

[24] Islandora Solution Packs [Internet]. [updated 2017 Jul 13] .LYRASIS Wiki; [cited 2020 Dec 08].

Available from: https://wiki.lyrasis.org/display/ISLANDORA/Solution+Packs#:~:text=Islandora%20Solution%20Packs%20are%20Drupal,as%20books%20or%20audio%20files

Appendix I

Press release

Life in Washington During COVID-19 Captured in Library’s “Archive This Moment D.C.” Collection

88 photos submitted by District residents in DC Public Library’s first release of collection showing daily activities and sights during city’s stay-at-home order

(Washington, D.C.) – As the District shut down for the COVID-19 stay-at-home order in April, the marquee on the Anthem music venue says, ‘We’ll get thru this.” At the World Central Kitchen in the U Street Corridor, Dreaming Out Loud program alumni donned face masks while preparing meals for seniors and homebound residents.

These are two of the 88 photos in the initial release of DC Public Library’s “Archive This Moment D.C.,” a collection created by Washingtonians capturing what people were thinking, feeling and doing during the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The photos were submitted by people posting on Instagram using the hashtag #archivethismomentdc. From March 25 to May 28, the Library collected more than 2,000 images from social media, through email and a web form. The majority of the items were collected in April, followed by May and March.

Telling stories of COVID-19 from the viewpoint of the people who lived through it, makes the Archive This Moment D.C. collection an invaluable resource for the District, said Richard Reyes-Gavilan, executive director of the DC Public Library. “Some of the most important accounts of history are first-person. This collection will help future researchers understand how residents reacted to the pandemic, and how quickly it changed the way we all lived.”

The collection includes selfies and portraits of people in masks; handmade signs of support of essential works and the community; people navigating the city during the pandemic; and signs posted in business windows about closures, restrictions, and new business protocols. When complete, the “Archive This Moment” collection will consist of images, audio recordings, videos, and text.

All four quadrants of the District are represented. This initial release includes images from the Atlas District, Barney Circle, Bloomingdale, Capitol Hill, Carver Langston, Cleveland Park, Downtown, Dupont Circle, Eckington, Georgetown, Kingman Park, Logan Circle, Manor Park, Mount Pleasant, Southwest, U Street Corridor, West End and Woodley Park.

Since the Library began collecting images, librarians have been working behind the scenes creating complete records of the materials. Every item added to the collection receives a unique identifier, title, description, and a Library of Congress subject heading so that people can find the items easily. All original captions from Instagram and Twitter are saved as PDF files to preserve emojis and other special characters. As more items are cataloged, the collection will increase.

The Archive This Moment D.C. collection is housed on Dig DC, the Library’s web portal for digitized and born-digital special collections items. To view the collection, visit https://digdc.dclibrary.org/.

###

Appendix II

First Pass Selection Criteria

If you answer NO to ANY of these questions about the submissions, the submission does NOT pass the first pass of selection criteria:

- Was it created within the official boundaries of Washington, D.C. and/or does it document the people, places, and ways of life within the official boundaries of Washington, D.C.?

- Was it created after March 1, 2020?

- Was it created before May 28, 2020?

- Was it created by the submitter?

- If submitted through social media, was it posted by a public account?

Absolute Yes Criteria (apply to content after asking the above questions)

- Tells the story of daily life in the District during this period of social distancing

- Obviously documents what has changed – recently posted rules on social distancing, face masks, empty streets, related street art

- No: protests, faces of kids, or private info like phone numbers, addresses, Doctor’s names, or other personal or health information

Maybe:

- Anything you feel like should be looked over by the group: put in the Notes field why you weren’t certain

- Protests, faces of kids, or private info like phone numbers, addresses, Doctor’s names, or other personal or health information

- Contact creator to inquire if they would like this to be added to our collection

- If they answer “no” or we do not receive a response, these will not be selected

2nd Pass – Final Selection Criteria

- No to: protest or activist content; any personally identifying information

- Date created March 25-May 28, 2020

Appendix III

Steps used to Instagram convert Unix time metadata into ISO 8601 in Google Sheets

- Add a new date field column to the master spreadsheet

- Apply the formal =((A1-21600000)/86400000)+25569 to the appropriate column to convert the timestamp from Unix time to ISO 8601

- Change the format of the new date column using Format>Number>Date time

- Remove the hours:minutes:seconds portion of the timestamp using Data>Split text to columns>Separator: Space and delete the extra split column.

Appendix IV

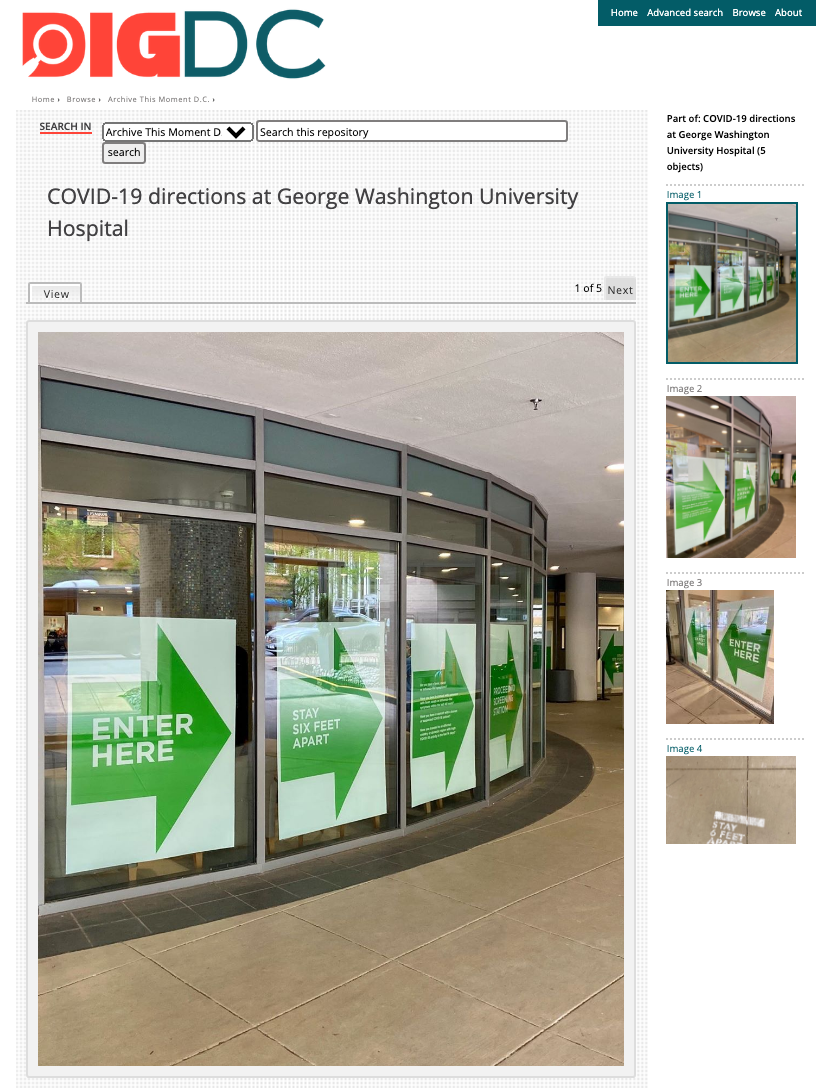

Figure 1. Example of Archive This Moment digital object with files grouped together to emulate the original Instagram Post. https://digdc.dclibrary.org/islandora/object/dcplislandora%3A267598<

Appendix V

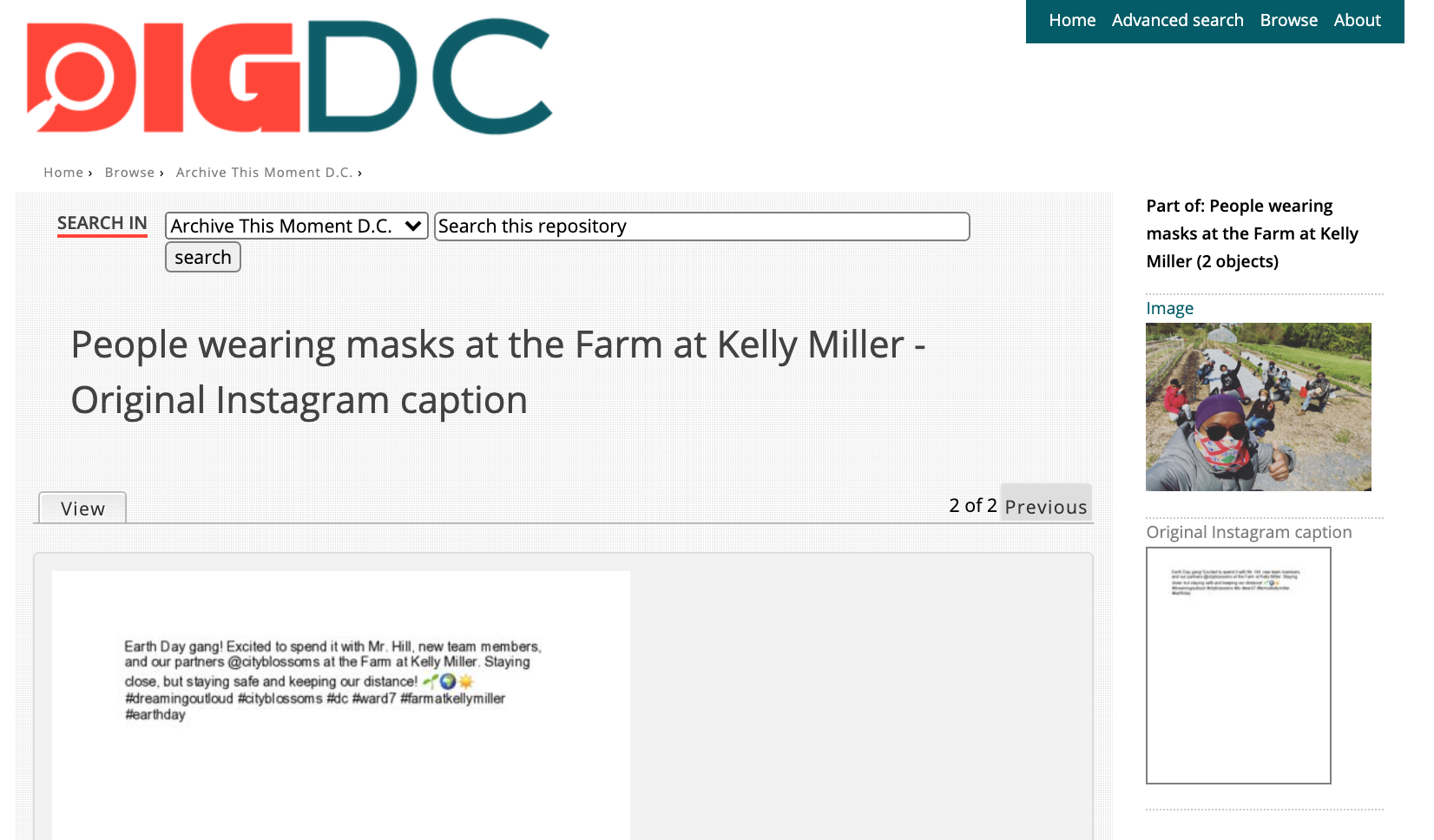

Figure 2. Example of Archive This Moment D.C. digital object with original Instagram caption captured as a PDF. https://digdc.dclibrary.org/islandora/object/dcplislandora%3A267888

Figure 3. Example of Archive This Moment D.C. digital object with original Instagram caption captured as a PDF. https://digdc.dclibrary.org/islandora/object/dcplislandora%3A267888

Appendix VI

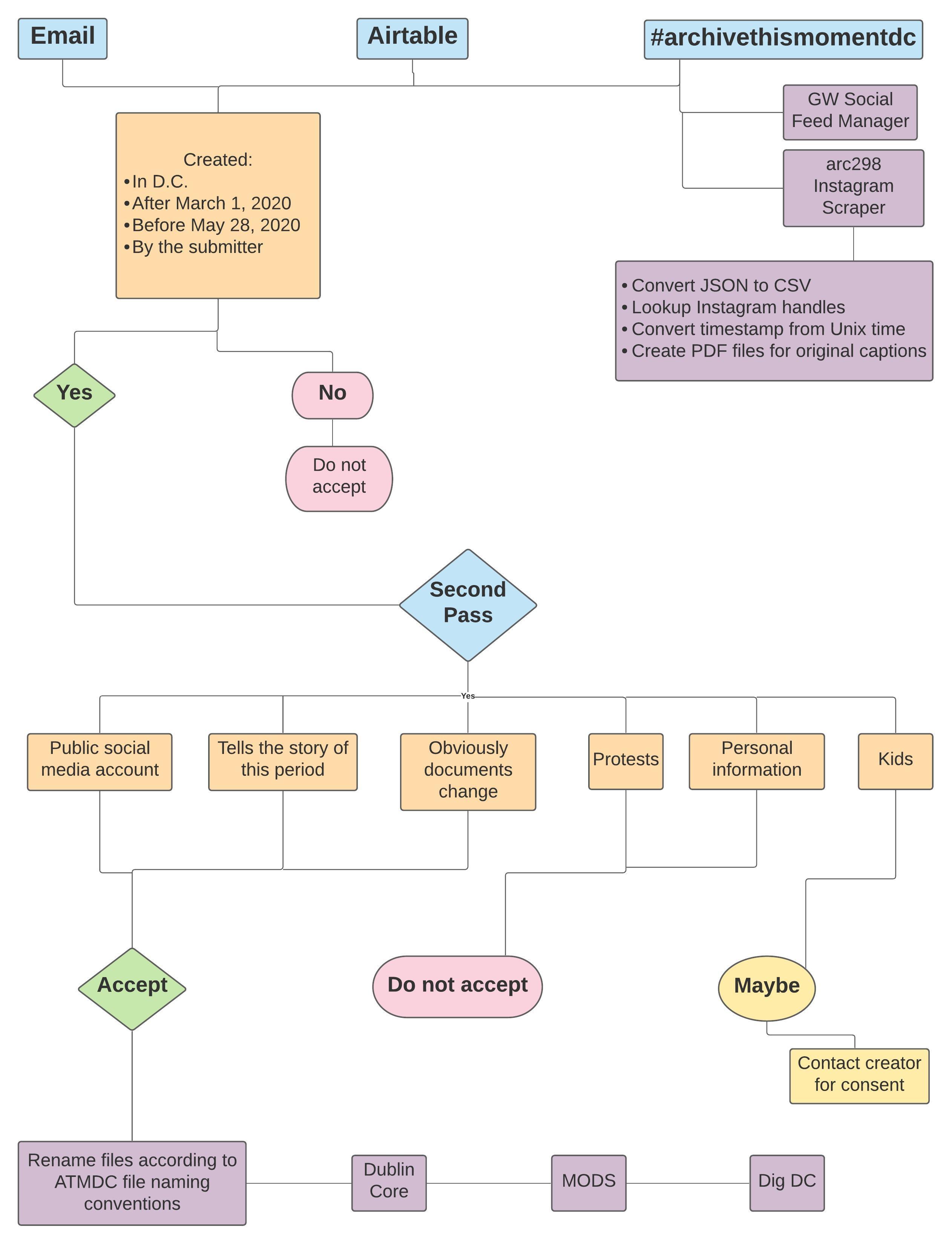

Figure 4. Archive This Moment D.C. project workflow.

About the Authors

Julie Burns (julie.burns@dc.gov) is a Library Associate for the People’s Archive at DC Public Library. She holds an M.A.T. in Museum Education from the George Washington University and a B.A. in English from the University of Mary Washington.

Laura Farley (laura.farley@dc.gov) is the Digital Curation Librarian for the People’s Archive at the DC Public Library. She holds her M.A. in Library and Information Studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a B.A. in History from the University of Iowa. Laura’s passion is shining a light on our shared histories through accessibility and outreach.

Siobhan C. Hagan (siobhan.hagan@dc.gov) is the Project Manager of the DC Public Library Memory Lab Network. Siobhan is also the Founder & CEO of the Mid-Atlantic Regional Moving Image Archive (MARMIA) and holds her M.A. in Moving Image Archiving and Preservation from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts.

Paul Kelly (paul.kelly2@dc.gov) is Digital Initiatives Coordinator for People’s Archive at DC Public Library. He holds his M.S. in Library and Information Science from the Catholic University of America and M.A. in English Literature/Film and Television Studies from the University of Glasgow. His professional interests include collections as data, web archiving, and digital preservation.

Lisa Warwick (lisa.warwick@dc.gov) is the Reference Coordinator for the People’s Archive at DC Public Library. She holds her M.A. in Information Science from the University of Maryland and a B.A. in Film Studies from the University of Pittsburgh. Her passion is using history to connect individuals to community.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply