By Barbara I. Dewey

Introduction

Why is an action framework appropriate for advancing library technology diversity? Developing a framework and its accompanying dimensions requires a focus and provides a context for a more comprehensive way to advance diversity. Typically frameworks are developed as conceptual. The notion of an action framework includes the conceptual but underscores the importance of visible and concrete action. I was inspired to consider and develop the action framework for library technology diversity by The Framework to Foster Diversity at Penn State: 2010-2015 project. The Framework consists of seven strategic challenges for building a truly diverse, inclusive, and equitable institution. They are:

Challenge 1: Developing a shared and inclusive understanding of diversity

Challenge 2: Creating a welcoming campus climate

Challenge 3: Recruiting and retaining a diverse student body

Challenge 4: Recruiting and retaining a diverse workforce

Challenge 5: Developing a curriculum that fosters United States and cultural competencies

Challenge 6: Diversifying university leadership and management

Challenge 7: Coordinating organizational change to support our diversity goals [1]

Naturally these challenges are broad and institutional in scope but provide a way of thinking about advancing diversity in more specific and measurable ways.

Transforming Knowledge Creation: An Action Framework for Library Technology Diversity

The specific action framework for technology diversity, comprised of five dimensions, is based on the core mission and vision of the library:

Mission: The University Libraries inspire intellectual discovery and learning, offer robust information resources and academic collaborations in teaching and research, and connect the Penn State community and residents of Pennsylvania to the world of knowledge and new ideas.

Vision: The University Libraries will be a world-class academic library with a global reach; a welcoming and inclusive environment for learning, collaboration, and knowledge creation; a partner in research and education; a leader in delivery and preservation of library collections; and a place that uses technology and rewards innovation.

Why focus on knowledge creation? I believe knowledge creation is at the heart of libraries’ existence and remains so in perpetuity. The framework for library technology diversity can be developed through the lens of knowledge creation. In the context of diversity, the process of knowledge creation needs be inclusive and expansive if its purpose is to advance understanding, solve global problems, and advance the human condition. Embracing concepts of intellectual freedom which are fundamental to our values in libraries and in the academy is woven into the mission and vision. Everything we do with library technology diversity relates to these concepts. Thus, the following comprise framework dimensions for advancing technology diversity, not only in the library, but throughout the university.

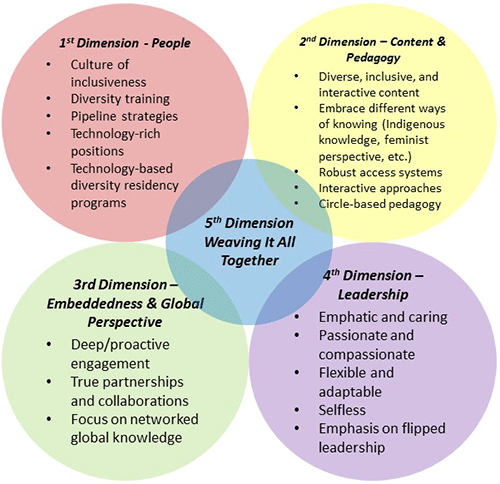

Figure 1. Transforming Knowledge Creation: An Action Framework for Library Technology Diversity – The 5th Dimension Weaves it all Together

Dimension 1: People

Library workers and technologists come from a variety of disciplines but are clustered in library and information sciences (LIS) and computer science/engineering. There is still a lack of diversity and gender equity in the computer science and computer engineering fields; however, these inequities are not as great in information degrees and programs offered by Library and Information Science schools (LIS) and “I-Schools” such as information studies, information sciences, informatics, and information technology (McInerney 2015). [2] Also, an NSF report, Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering: 2013, noted that family was a predominant reason why people of diverse backgrounds did not work full or part-time in science and engineering. Recruiting students from diverse backgrounds is an important component to increasing the pipeline. Lord and Cohoon (2007) [3] provided the following strategies:

- Have prospective students meet with faculty/staff who understand diversity

- Arrange for prospects to meet with students from diverse backgrounds

- Cultivate and publicize the inclusive aspects of department culture

- Utilize diversity training to increase awareness of effective actions and ways to avoid bias

These I-School and LIS programs can be the entry point for technology-rich positions especially with the growth of new position configurations such as:

- Data curation specialists

- Rich media specialists

- Visualization specialists

- Science data librarians

- Data learning librarians

- Discovery and access specialists

- Web specialists

- Accessibility specialists

- User experience specialists

- Interface developers

- Learning design specialists

- Online learning specialists

- Electronic publishing specialists

- Digital learning specialists

- Project managers

Recruitment strategies for incoming students to then take IT-related positions in our libraries and IT departments will take time. A more immediate strategy is to launch programs focused to broaden the diversity of applicant pools. One such program is Penn State’s Library Diversity Residency Program. This program attracts recent Library and Information Sciences graduates from historically underrepresented groups for a two-year experience in academic librarianship. The purposes of this program are to:

- Increase diversity among Penn State Libraries’ faculty

- Increase diversity in the field of academic librarianship

- Invigorate the organization with fresh ideas, skills and enthusiasm

- Prepare library leaders for the future

- Enhance Penn State’s reputation as an institution that supports, trains, and mentors diverse librarians

The proposed program grew out of the University Libraries’ longstanding commitment to diversity. It supports the University’s Strategic Plan, particularly strategy 2.1 “Faculty Recruitment and Retention for Excellence”, which includes the University’s commitment to increase diversity among faculty, and strategy 4.3 “Build on the Framework to Foster Diversity”. Within the Framework to Foster Diversity, Challenge 4 “Recruit and Retain a Diverse Workforce” and Challenge 6 “Diversify University Leadership and Management” both directly benefit from a Diversity Residency Program.

The Libraries’ Diversity Residency Program is a two-year faculty appointment. In the first year, participants experience assignments in a variety of areas of the Libraries on a rotational basis. All of the assignments include a technology component and relate to the University Libraries areas of priority:

- Digital initiatives

- Emerging technologies

- Instructional and research services

- Repository and data curation services

Residents participate actively in University and Libraries committees, councils and task forces. They develop collegial relationships with Penn State faculty members and provide support in a variety of ways for students. Residents also contribute to national and regional professional organizations.

Upon completion of the Diversity Residency Program, participants are eligible for continued employment by Penn State, subject to the availability of appropriate positions and opportunities, and are well prepared for opportunities in the field of academic librarianship, including positions at other institutions. Residents bring rich and diverse knowledge and perspectives to the library resulting in new programs and initiatives.

Dimension 2: Content and Pedagogy

Libraries have always focused on content to support knowledge creation, and academic libraries have the reputation of being comprehensive. A recent presentation at Penn State by Chris Bourg (2013) confirmed huge content gaps in even the largest academic libraries and universities. She noted that they are shockingly lacking in depth when it comes to actually representing the world’s knowledge. This is because of the way we choose and build content and curriculum. Books and journals from many parts of the world are not collected, are not part of the interlibrary loan world, are not digitized, and are not embedded or a part of the “western” scholarly record. Likewise, scholarship coming from diverse voices is not always collected and is slow to become part of the canon, and therefore, unavailable to researchers for knowledge creation. Societal issues related to power, discrimination, and disenfranchisement stem, in part, from the distortion in the historical record upon which knowledge is created.

Systems for content access are also limiting in terms of completeness and attention to diversity. Sanford Berman tackled the misrepresentation of knowledge in his 1971 seminal work, Prejudices and Antipathies: A Tract on the LC Subject Headings Concerning People. [4] Librarians schooled in the 1970s, a period of great world unrest, will vividly recall his contributions. Unfortunately his work is largely forgotten today. He focused on the bias, bigotry, and shear ignorance of the Library of Congress subject headings, a large part of the library mapping schema. He writes (1971: xi):

Knowledge and scholarship are, after all, universal. And a subject-schema should, ideally, manage to encompass all the facets of what has been printed and subsequently collected in libraries to the satisfaction of the worldwide reading community…But in the realm of headings that deal with people and cultures—in short, with humanity—the LC list can only “satisfy” parochial, jingoistic Europeans and North Americans, white-hued, at least nominally Christian (and preferably Protestant) in faith, comfortably situated in the middle-and higher-income brackets, largely domiciled in suburbia, fundamentally loyal to the Established Order, and heavily imbued with the transcendent, incomparable glory of Western civilization.

His work, thought by some to be overly strident and radical at the time, eventually moved the Library of Congress and the library profession to change, albeit slowly, the most obvious of the biased LC subject headings and to acknowledge the flawed nature of the schema. This schema is still based on published works held in libraries and does not adequately address knowledge found in many other forms. Today we can employ new metadata schemas and technologies to increase access to a wider array of resources for rich knowledge creation more representative of the world’s collective minds. These deficiencies and gaps in knowledge discovery hold serious consequences for expansive knowledge creation.

Academic libraries are embracing 21st century approaches to support indigenous knowledge stewardship and creation. For example, at Penn State the University Libraries collaborates with the Interinstitutional Consortium for Indigenous Knowledge (ICIK), which is a global network of more than 20 indigenous knowledge resource centers across the world. ICIK is a network that promotes communication between those who share an interest in diverse local knowledge systems. These local knowledge systems are an integral part of current and future knowledge creation. The ICIK initiatives highlight the growing awareness of ways of knowing through a broad definition of ways of knowing in our global society. A center piece for ICIK is the Center for Indigenous Knowledge and Rural Development Collection, a unique collection comprised of 11 subject areas related to indigenous knowledge, originally collected by the late Dr. Michael Warren, a renowned anthropologist from Iowa State University. [5] An online bibliography is available, and plans are underway to digitize at least part of the collection. ICIK, its collections, and its programming have inspired partnerships to reveal different ways of knowing and knowledge creation.

The University of Texas Libraries Human Rights Documentation Initiative (HRDI) is an important example of collecting radically different but critically important content and the importance of their use. [6] In 2007 the HRDI was formed to preserve the most vulnerable records of human rights struggles worldwide. In most cases these are born digital records. Texas has made important strides locating these fragile resources, preserving them as evidence and memorial, and making them available to conflict survivors, scholars, activities, and students of human rights.

Diversity initiatives in the way we build and provide access to content is an important dimension of the framework. Penn State University Libraries, along with other libraries, have embodied the imperative to advance alternative ways of knowing through proactive programming and innovative approaches to collection development. Through this process we are learning more about the knowledge, expertise, and literacy components needed to support the incorporation of different ways of knowing in all aspects of library work and consequently in knowledge creation. These efforts require creative and expansive approaches to technological solutions for discovery, digitization, different models of ownership, and preservation.

Content combined with pedagogy is an important dimension of our diversity framework for library technology. Gregory and Higgins explore, through essays in the book Information Literacy and Social Justice, critical theoretical approaches to librarians’ work. In their words, “we consider the historical, cultural, social, economic, political and other forces that affect information so that we may explore ways to critique our understandings of reality and disrupt the commonplace; interrogate multiple points of view, to identify the status quo and marginalized voices; and focus on sociopolitical issues that shape and suppress information in order to take informed action in the world.” [7]

Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, now housed permanently in the Brooklyn Museum was conceived as a way to expose famous women throughout history using techniques that were traditionally not considered true art, such as ceramics painting and needlework. In her words, “I had been trying to establish a respect for women and women’s art; to forge a new kind of art expressing women’s experience; and to find a way to make that art accessible to a large audience.” [8] This alternative way of knowing about women’s culture through the ages also needs to be preserved and curated. Judy Chicago found a way, a schema, and a mapping strategy with The Dinner Party to present knowledge and ethos in a new way.

The Dinner Party provided the basis for The Judy Chicago Art Education Archives. Archivists and art education faculty members are using the collection and the Chicago “living” curriculum pedagogy to provide students with a transformative way of learning how to teach art. The students in this process are also made aware of a new paradigm and way of knowing from a feminist perspective. [9]

Judy Chicago’s recent work, Institutional Time: A Critique of Studio Art Education, provides a basis for dialogue and a case study for transforming curriculum, not just in Studio Art Education, but with other curriculums guiding research and creativity. [10] Chicago instituted a pedagogy particularly responsive to the concerns of women artists on what she terms “circle-based pedagogy,” enabling all to participate. She talks about a “living curriculum” based on values and beliefs, framed around encounters, creating new ways to think about a variety of topics, and, themselves, create a living curriculum.

The development of the Judy Chicago Art Education Portal to discuss issues of pedagogy is another example of interactive and living archives which provide an alternative means of documenting ideas and advancing scholarship and teaching. The Portal is being launched in four stages and has already garnered international attention:

- An Invitation from Judy Chicago – which features a video of Chicago discussing major tenets of her pedagogy and a multimedia presentation by Penn State Art Ed faculty member Karen Keifer-Boyd.

- Difference in Studio Art Teaching: Applying Judy Chicago’s Pedagogical Principles highlights projects utilizing Judy Chicago’s Art Education Archives and the application of her teaching pedagogy in courses taught at Penn State.

- What about Men addresses the often contentious subject of men in a feminist environment and takes up the challenges of making institutional changes in terms of curriculum.

- Transforming Curriculum will showcase sculptor Bill Catling who discusses how to achieve a radical transformation in arts education in both policy and curriculum. [11]

The Portal is a great example of how technology, itself, can support alternative ways of dialogue and understanding in addition to focusing on content.

Penn State hosts the Sister Joan D. Chittister Archive in partnership with the Benedictine Sisters of Erie and Mercyhurst College which emphasizes different ways of knowing and global peace and justice initiatives. Sr. Joan, internationally known writer and lecturer and one of the most articulate social analysts and influential religious leaders of this age, has established an archival collaboration for the preservation of her accumulated works. Her emphasis on social justice provides alternative ways of knowing about the world, peace, and faith, especially from a radical Benedictine nun’s point of view. Sr. Joan saw The Dinner Party when it was on display in Cleveland, Ohio in 1981. She noted that many of the women in the installation were religious figures such as Sophia from the Old Testament, Judith from Saint Bridget, and Hildegarde of Bingen, to name a few. Chicago’s work had a profound impact on her, so much so, that she subsequently arranged for three buses to take all of the Erie, Pennsylvania Benedictine nuns to Cleveland to see The Dinner Party. She next worked with a committee to encourage each chapter of the Federation of Saint Scholastica to create a version of The Dinner Party symbolizing women in their religious communities. In 1982 at the federation’s meeting the sisters set up their installation and discussed the failure of the Church to recognize women’s contributions through time. Another gap in the religious history curriculum was filled that day through alternative ways of viewing and creating knowledge and it is interesting for students and researchers to see the connection between these two amazing women.

Dimension 3: Embeddedness and the Global Perspective

The presence of embeddedness and the global perspective form a third dimension emphasizing “knowing” from within groups, cultures, regions, and perspectives. Examining the framework from a global perspective acknowledges the broad context of scholarship as well as the imperative for diverse perspectives and connections. Effective support for and engagement with research, teaching, and learning depends on connections, collaborations, and partnerships at levels never seen before. The notion of embeddedness is key to understanding and engaging with different perspectives and, in itself, is a key component of the framework. In 2004 I wrote:

The concept of embedding implies a more comprehensive integration of one group with another to the extent that the group seeking to integrate is experiencing and observing, as nearly as possible, the daily life of the primary group. Embedding requires more direct and purposeful interaction than acting in parallel with another person, group, or activity. [12]

Purposeful and overt engagement with diverse populations, cultures, and activities is central to advancing global perspectives. The inclusion of global perspectives acknowledges the broad context of scholarship and its rapidly changing formats. Libraries throughout the world are, more and more, managing abundance rather than scarcity of resources. This kind of management requires acute comprehension of relevant physical and virtual environments in a global context. Library technologists and technologies they employ must adapt to the global landscape. A core part of this adaption is deep learning about the networked global information environment through the eyes of the 21st global scholar.

Dimension 4: Leadership

Librarians and technologists are well positioned to play leadership roles in advancing diversity within the library and throughout the institution IF we surface our inherent commitment to embracing people and the multitude of ideas reflecting the breadth and depth of the human experience. Furthermore, a comparison can be made of themes in Institutional Time and in the 2013 book by Maria Accardi, Feminist Pedagogy for Library Instruction. [13] Both works talk about the benefits as well as the resistance to a caring and collaborative learning environment. While both are written from feminist perspectives they underscore the issue of caring and empathy which are now being recognized as fundamental to leadership success.

Leadership traits in dimension four are empathy, strategic vision, and commitment to collaboration. Leadership at all levels is committed to technology as a public service and keenly understands its potential to transform teaching, research, and learning endeavors, forge new knowledge and preserve it for continuing access. Leadership is flexible and adaptable embracing and encouraging innovation and experimentation. Flexibility and adaptability are key. Passionate and compassionate leadership is the new normal for advancing, not only diversity, but the mission of the university. The framework embraces selflessness and eschews self-centeredness. The new leadership is also:

- Selfless and user centered (not selfish and ego-centric)

- Respectful (not disrespectful)

- Collaborative (not solitary)

- Flexible (not rigid)

- Outwardly focused (not inwardly focused)

- Proactive (not reactive)

This new kind of leadership is based on these core values and traits that epitomize the ability to work across and respect all cultures and points of view. It mirrors the fact that we support everyone regardless of discipline, location, or status. We can lead the way to advance global scholarship and understanding.

The fourth dimension of leadership also places major emphasis on what I have coined as “flipped” leadership. Just as with the flipped classroom concept, flipped leadership provides the opportunity for librarians and technologists at all levels and from all backgrounds to engage in meaningful leadership roles in the library and throughout the campus. Flipped leadership increases the depth and breadth of library presence at more tables bringing deep expertise to the initiatives at hand.

The 5th Dimension: Bring the Dimensions together into the Framework for Library Technology Diversity

People, Content and Pedagogy, Embeddedness and Global Perspectives, and Leadership combine to form the Framework for Library Technology Diversity – the 5th Dimension. The end result is a dynamic approach to advance knowledge creation which is truly reflective of the diversity of thought, practice, and cultural perspectives. The Framework leverages expertise, technology, and leadership to ultimately advance the human condition and provide creative solutions to global challenges through its dimensions and combinations of dimensions. The mission of the university and the library in a multidimensional world is to create knowledge. The 5th Dimension fulfils this mission and “Lets the Sunshine In.” [14]

Conclusion

The Framework for Library Technology Diversity and its five dimensions providess a way to look across areas of the library, the university, and the world to advance diversity and increase humankind’s ability to solve problems and create new knowledge for the future. Library technology workers are ideally suited to recognize and support different ways of knowing in all of the dimensions of the Framework. We need to set them free with the proper support to lead this work.

Notes

[1] The Framework to Foster Diversity at Penn State: 2010-2015, http://equity.psu.edu/framework/, Accessed February 13, 2015. http://equity.psu.edu/framework/

[2] Claire McInerney, “What can LIS Offer Men and Women in the Pipeline for Technology Careers?” Panel on Re-examining Issues of Gender and Sexuality in LIS Teaching, Research, and Service Delivery presented at ALISE ’15 – Mirrors & Windows: Reflections on Social Justice and Re-Imagining LIS Education, January 29, 2015.

[3] H. Lord and J.M. Cohoon, “Recruiting and Retaining Women Graduate Students in Computer Science and Engineering. Report on Research Findings and Workshop Recommendations,” Washington, DC: CRA (October 8, 2006).

[4] Sanford Berman (1971). Prejudices and Antipathies: A Tract on the LC Subject Heads Concerning People.Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press: xi

[5] Penn State ICIK and Penn State Cikard, Accessed February 13, 2015. http://icik.psu.edu/psul/icik.html, http://icik.psu.edu/psul/icik/cikard.html

[6] University of Texas Libraries Human Rights Documentation Initiative, http://www.lib.utexas.edu/hrdi/, Accessed February 13, 2015.

[7] Lua Gregory and Shana Higgins, Information Literacy and Social Justice: Radical Professional Praxis, Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press (2013).

[8] Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party: A Symbol of Our Heritage. Garden City New York: Anchor Books (1979): 12.

[9] Penn State University Libraries. The Judy Chicago Art Education Archives, Accessed February 13, 2015 http://judychicago.arted.psu.edu/

[10] Judy Chicago, Institutional Time: A Critique of Studio Art Education. The Monacelli Press (2014).

[11] The Judy Chicago Art Education Dialogue Portal. Accessed February 16, 2015. http://judychicago.arted.psu.edu/dialogue/

[12] Barbara I. Dewey, “The Embedded Librarian: Strategic Campus Collaborations,” in Libraries Within Their Institutions: Creative Collaborations edited by William Miller and Rita M. Pellen. New York: Haworth Press (2004): 6.

[13] Maria T. Accardi, Feminist Pedagogy for Library Instruction. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press (2013).

[14] Referencing the hit single Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In (1967) by James Rado, Gerome Ragni, and Galt MacDermot originally written for Hair and later released by the 5th Dimension.

About the Author

Barbara I. Dewey is Dean, University Libraries and Scholarly Communications, at the Pennsylvania State University. She was Dean of Libraries, University of Tennessee, Knoxville from 2000-2010. Previously, she held several administrative positions at the University of Iowa Libraries including Interim University Librarian. Prior to her work at Iowa she held positions at Indiana University’s School of Library and Information Science, Northwestern University Libraries, and Minnesota Valley Regional Library in Mankato, Minnesota. She is the author/editor of six books, and has published articles and presented papers on research library topics including digital libraries, technology, user education, fundraising, diversity, organizational change, and human resources. She holds the M.A. in library science, the B.A. in sociology/anthropology from the University of Minnesota, the Public Management Certificate from Indiana University. She is on the SPARC Steering Committee and ARL’s Statistics & Assessment committee.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply