by Nick Ruest and Ian Milligan

Introduction

During the 2015 Canadian federal elections, we captured 3,918,932 tweets written using the #elxn42 hashtag: thoughts on the nature and stature of political candidates or parties, live running commentary during leader debates, exhortations to vote, and witty ripostes or jokes to liven up the long campaign. Political scientists, journalists, and other researchers can use these tweets as evidence of sentiment amongst a certain slice of the electorate: did a policy go over well? Did it not? What tweets get re-tweeted, or further shared, and which ones do not? If these are questions that resonate amongst contemporary researchers, historians are also interested in the long-term preservation of digital material. Tweets, as well as the much broader scope of archived webpages and born-digital data, are the primary sources of tomorrow. Tweets present considerable advantages in that they represent the preservation of material representing the voices of everyday people that might not otherwise be saved, but also considerable challenges in the collection and use of data on such a large scale. If the norm until the digital era was to have human information vanish, “now expectations have inverted. Everything may be recorded and preserved, at least potentially” (Gleick, 2012). Useful historical information is being preserved at mind-boggling rates that continue to accelerate. IBM Research, for example, notes that “every day, we create 2.5 quintillion bytes of data — so much that 90% of the data in the world today has been created in the last two years alone.” (IBM Research, 2016)

This data has the potential to reshape multiple avenues of historical research. In the case of the #elxn42 hashtag, we have access to the tweets of some 318,176 unique users (which would include some bots and spam accounts, of course). Consider what the scale of this dataset means. Social and cultural historians will have access to the thoughts, behaviours, and activities of everyday people, the sorts of which are not generally preserved in the record. Military historians will have access to the voices of soldiers, posting from overseas missions and their bases at home. And political historians will have a significant opportunity to see how people engaged with politicians and the political sphere, during both elections and between them. The scale boggles. Modern social movements, from the Canadian #IdleNoMore protest focusing on the situation of First Nations peoples to the global #Occupy movement that grew out of New York City, leave the sorts of interactions that would rarely, if ever, have been recorded by previous generations. During the #IdleNoMore protest, for example, Twitter witnessed an astounding 55,334 tweets on 11 January 2013. If we were to take the median length of a tweet (60 characters), the average length of a word (5 characters plus a space), and think about 300 words per page, we’re looking at over 1,800 pages. This for a single day of a single social movement in the relatively small country of Canada.

While Twitter is certainly not a representative sample of broader society – Pew Research shows in their study of US users that it skews young, college-educated, and affluent (above $50,000 household income). We need to keep the demographic limitations of this source base in mind, as we do with all source bases. This is not a random sample of Canadian society, but a self-selecting portion of it (as with many non-digital archival collections as well). As a record of society, Twitter certainly suffers from selection bias. Yet, Twitter – and other web archives – will still represent an exponential increase in the amount of information generated, retained, and preserved by everyday people.

Therefore, when historians study the 42nd federal election, we believe that Twitter will be an important source.

Recognizing Twitter’s significance, it calls out for active preservation. Once an event has happened, if a small window of time has passed – 7 to 9 days – the tweets become largely inaccessible on a large scale without considerable monetary resources. While the Library of Congress archives tweets, it remains unclear how their access regime will work. Yet using a combination of several open-source tools, librarians, archivists and other researchers can do the following:

- create their own Twitter archives using

twarc; - analyse tweets using

twarc-reportandtwarc-utilities; - visualize the material;

- use Twitter as a launchpad for further web archiving activities; and

- share tweet IDs with an eye to sharing collections in accordance with the Twitter Developer Agreement & Policy.

This article walks users through these five steps, with an eye to presenting this as a model for other forms of analysis. Libraries, spread across the world, can collect hashtags of local or national significance, taking a step towards the more widespread preservation of today’s cultural record.

Creating your Own Twitter Archive: Data Collection

The Web Archives for Historical Research Group began capturing #elxn42 tweets on August 3, 2015 with twarc. “twarc is a command line tool and Python library for archiving Twitter JSON data. Each tweet is represented as a JSON object that is exactly what was returned from the Twitter API. Tweets are stored as line-oriented JSON. Twarc runs in three modes: search, stream and hydrate. When running in each mode twarc will stop and resume activity in order to work within the Twitter API’s rate limits.” (Summers, et al, 2015)

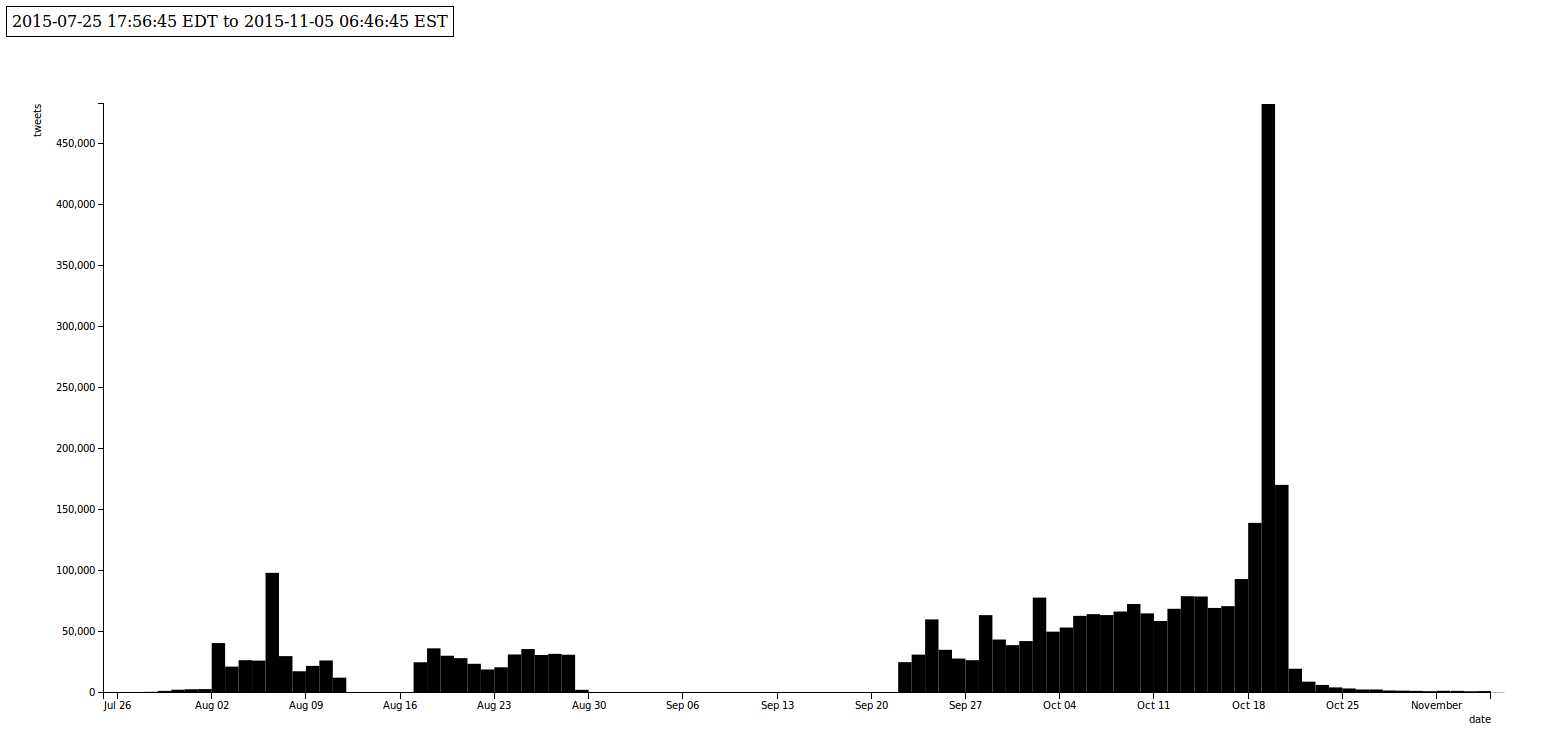

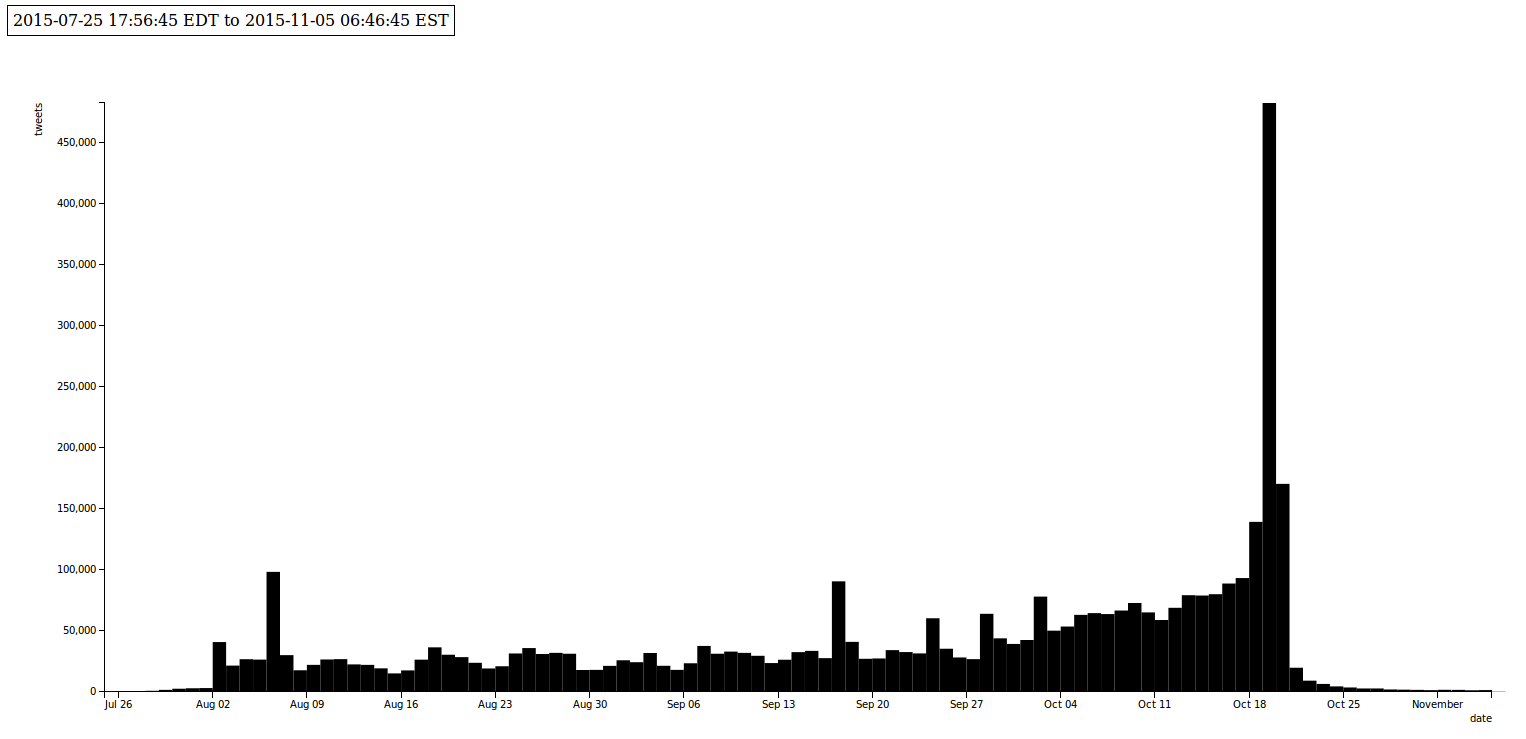

On August 3, the team initiated both a search API and stream API collection with twarc using the hashtag #elxn42. The search API was used to gather any tweets with the #elxn42 hashtag before initial collection date. The stream collection mode was initiated with the intention to gather #elxn42 tweets for the entirety of the election. However, we noticed that twarc had silently failed during September, and the research team did not notice. We believe the failure here was because of an issue with the Twitter API or network connection issues, but it is not clear, and we are not confident as to why we had a silent failure. As a result we lost 27 days in total. Upon realization of the collection failure, the research team immediately began collecting via the stream API and began search API collection (allows collection back 7-9 days) simultaneously. Data Collection was stopped on November 5, 2015, the day after Justin Trudeau was sworn in as the 42nd Prime Minister of Canada. A total of 102 days, 13hrs and 50 minutes.

In retrospect, the research team recommends using a combination of collection via the Search and Streaming API. We would use a Streaming API collection over the period of the capture, as well as weekly Search API collections. Then, at the end of data collection and concatenating all the files together, we would deduplicate the entire dataset.

Library and Archives Canada (LAC) also collected the #elxn42 hashtag, using the Search API, during a similar time period; August 11, 2015 – October 28, 2015. The team made use of the LAC #elxn42 capture by downloading their tweet id dataset (Library and Archives Canada, 2015), and hydrating it. Once the LAC dataset was hydrated, the team combined their original dataset (Ruest, 2015) with the LAC dataset, and deduplicated it (Ruest et al, 2015).

$ twarc.py --hydrate elxn42-tweets-LAC.txt > elxn42-tweets-LAC.json $ cat elxn42-tweets.json elxn42-tweets-LAC.json > elxn42-tweets-combined.json $ python ~/git/twarc/utils/deduplicate.py elxn42-tweets-combined.json > elxn42-tweets-combined-deduplicated.json

This does not necessarily mean that between LAC and our research group that we captured all tweets. Driscoll and Walker (2014) have shown substantial differences in what is captured using Twitter’s commercial Gnip service versus the streaming API. While the #elxn42 hashtag never exceeded the hard limit of 1% of all tweets enacted using the streaming API – which comes into play if the volume of tweets you are capturing exceeds 1%, common in cases such as high-profile events (the Paris shootings or an American presidential debate) – there is still a chance that some content was not collected.

How Do You Collect?

Collecting tweets is very straightforward. Once you install and configure twarc, you can collect tweets using the Twitter Stream and Search APIs. As noted below, syntax changed slightly with twarc 0.5.0 so we have provided both as an example:

Search API: twarc.py --search "#elxn42" > elxn42-search.json

Stream API ( < v0.5.0 twarc): twarc.py --stream "#elxn42" > elxn42-stream.json

Stream API ( > v0.5.0 twarc): twarc.py --track "#elxn42" > elxn42-stream.json

These two APIs complement each other well. The Search API provides historical search on a given query, such as #elxn42, stretching back somewhere between six and nine days of tweets. Their API cautions that “the Search API is focused on relevance and not completeness. This means that some tweets and users may be missing from search results.” Given our project goals, this makes the Search API insufficient.

For completeness, then, we can turn to the Streaming API. This gives “developers low latency access to Twitter’s global stream of Tweet data,” up to the aforementioned 1% volume. Whereas Search API goes back into past tweets, Streaming only captures tweets as they happen. To put this into context, we could begin the Search API on #elxn42 on 5 September 2015 and still get tweets from 3 September 2015, for example; Streaming API cannot retroactively gather content. It is more complete, however.

A combination of the two is a recommended approach: the streaming API for the bulk collection, and the search API to fill in any gaps that may have happened when using the system.

Once collected, tweets can be shared with other people through the tweet IDs, which can be rehydrated using twarc. As twarc’s README notes:

The Twitter API’s Terms of Service prevent people from making large amounts of raw Twitter data available on the Web. The data can be used for research and archived for local use, but not shared with the world. Twitter does allow files of tweet identifiers to be shared, which can be useful when you would like to make a dataset of tweets available. You can then use Twitter’s API to hydrate the data, or to retrieve the full JSON for each identifier. This is particularly important for verification of social media research.

The command:

twarc.py --hydrate elxn42-tweet-ids.txt > elxn42-tweets.json

will recreate the original tweet(s) in json format, provided the content is still available on Twitter. If you wanted to use our dataset, for example, it could be download in Scholars Portal Dataverse. If a user deleted their tweet between the time of our collection and the time of your rehydration, you would not gain access to that tweet.

Should You Collect? Ethical Considerations

Beyond the technical question of how to collect tweets comes the ever-important question of should you, and if so, how to handle the question of consent? Strictly speaking, we have legal permission thanks to the Twitter Developer Agreement & Policy. We can only capture public tweets, and given the tweets are public, we interpret that as consent in the broadest form to archive and preserve this material. Consent is not perpetual, as users may decide to make their account “private” after collection. Accordingly, when tweet ids are hydrated, only publicly accessible tweets are hydrated (indeed, as deleted or private tweets are not made available via the API, this is unavoidable – one cannot get data about a deleted tweet from Twitter).

So, if a tweet is deleted in the period between our capture and hydration, the tweet will not be hydrated. Similarly, if an account is public, and set to private in the period between our capture and hydration, the tweet will not be hydrated. We discuss this further in our section below on deleted tweets.

George Washington University’s Library has been exploring, as part of their work with the Social Feed Manager, a platform to collect social media data from Twitter, the legal and ethical implications of Twitter archiving. In a recent presentation at Web Archives 2015: Capture, Curate, Analyze, Seemantani Sharma, Vakil Smallen, and Daniel Chudnov (2015) explored the three primary legal areas of concern: copyright, privacy, and access. While in the United States, the issues surrounding fair dealing largely would not see tweets as copyrighted content, they accordingly focus much of their attention on the murkier area of the ethical concerns of privacy and access. Securing consent at the collection stage is largely unworkable, as Sharma, Smallen, and Chudnov note – making this a far trickier question.

As they note, and as we know, legal does not equal ethical, though. As Aaron Bady (2014) has noted, “[t]he act of linking or quoting someone who does not regard their Twitter as public is only ethically fine if we regard the law as trumping the ethics of consent.” As researchers at the University of Southern California discovered with their “Black Twitter Project,” many are uncomfortable with the prospect of their online content being harnessed without consent for research projects. (O’Neil, 2014)

Yet, if we do not archive this material, it could be lost forever: invaluable, diverse perspectives on unfolding events like the 2015 Canadian federal election. Collecting these tweets raises the prospect of a historical record not dominated by the mainstream media. We thus collect the material with the proviso that it needs to be ethically used by researchers. As Dorothy Kim and Eunsong Kim (2014) put it in their “#TwitterEthics Manifesto,” academics and those using this material in their work need to rethink their approach:

In the end, the work, the credit, the compensation, and the view need to be a shared, collaborative process. Twitter and New Media journalism, the internet and technology involves all of us. The voices on the platform are multiple, collective, dissenting, singular, and loud. You don’t need to speak for us–we are talking. Cite us, ask us to write, get our permission.

We collect the material so that it can be used. Researchers need to be ethically aware. When distributing the tweet IDs, we encourage them to use this material with respect.

Approach to Analysis

To analyze the data set, we took advantage of command line utilities, a number of utilities that are available with twarc and twarc-report, as well as jq. twarc-report is a set of utilities “for generating reports from twarc collections using tools such as D3.js.” (Binkley, 2015) The timeline graphs above were created with twarc-report. The command is as follows:

~/git/twarc-report/d3times.py elxn42-tweets-combined-deduplicated.json -a -o embed -t local -i 24H > elxn42-times.html

The flags do the following: -a aggregates output; -o specifies we wanted embedded output, -t specifies the timezone to use (local, or EST, in our case), -i sets the interval, in our case every 24 hours.

Upon completion of capturing #elxn42, the team immediately began aggregating their dataset into a single file. The team began with 12 different line oriented JSON object files totaling 22GB and 4,117,753 undeduplicated tweets. These 12 files were aggregated into a single file: cat *json > elxn42-tweets.json. Once aggregated, the dataset was validated with validate.py (ensuring that each line was a valid JSON object), and deduplicated (we have to dedupe given the combination of Search API and Stream API collection modes with twarc) using deduplicate.py. Once deduplicated, we were able to come up with the number of tweets collected. Since each tweet is a single JSON object representing a single line in the file, we were able to quickly calculate with simple command line utilities:

$ cat elxn42-tweets-combined-deduplicated.json | wc -l

Since Twitter automatically shortens URLs, the team also unshortened every URL in the dataset so that we would be able create a canonical list of URLs tweeted for further analysis. We were able to create this using a combination of tools; unshorten.py and unshrtn (“a small leveldb backed URL unshortening microservice written for node”).

$ sudo docker build --tag unshrtn:dev . $ sudo docker run -p 80:3000 -d -t unshrtn:dev $ cat elxn42-tweets-combined-deduplicated.json | ~/git/twarc/utils/unshorten.py > elxn42-tweets-combined-deduplicated-unshortened.json

With the URLs, we were able to run subsequent analysis: from creating a subsequent web crawl using the corpus in order to launch further explorations of an #elxn42 web crawl, to comparing coverage within the #elxn42 URL corpus with the broader Internet Archive, and beyond. This sort of derivative dataset can be very useful, especially given the URL-centric nature of the Wayback Machine.

Data Analysis and Results

Text

Using jq, we extracted all of the plain text of every tweet:

$ cat elxn42-tweets.json | jq -c '.text' | cat > elxn42-tweets-text.txt

This was useful for working with text analysis software, such as custom scripts written in R, Python, Mathematica, or even using the accessible online platform Voyant-Tools.

We were also interested in contrasting Twitter data by day, to see how it evolved. To do so, we used this following script:

#!/usr/bin/env python

#CC0 1.0 Universal

from __future__ import print_function

import sys

import json

import fileinput

import dateutil.parser

import dateutil.rrule

import pytz

import pandas as pd

import datetime

import io

eastern = pytz.timezone('US/Eastern')

start_date = dateutil.parser.parse("25-July-2015")

start_date = eastern.localize(start_date)

end_date = dateutil.parser.parse("06-November-2015")

end_date = eastern.localize(end_date)

dates = pd.date_range(start_date, end_date).tolist()

for date in dates:

date_plus_one = date + pd.DateOffset(1)

pretty_print = date.to_pydatetime().strftime('%Y%m%d')

filename = 'elxn42-tweets-' + pretty_print + '.json'

f = io.open(filename, 'w', encoding='utf-8')

for line in fileinput.input():

tweet = json.loads(line)

created_at = dateutil.parser.parse(tweet["created_at"])

created_at = created_at.astimezone(eastern)

if ((created_at >= date) and (created_at < date_plus_one)):

f.write(unicode(json.dumps(tweet, ensure_ascii=False) + '\n'))

f.close()

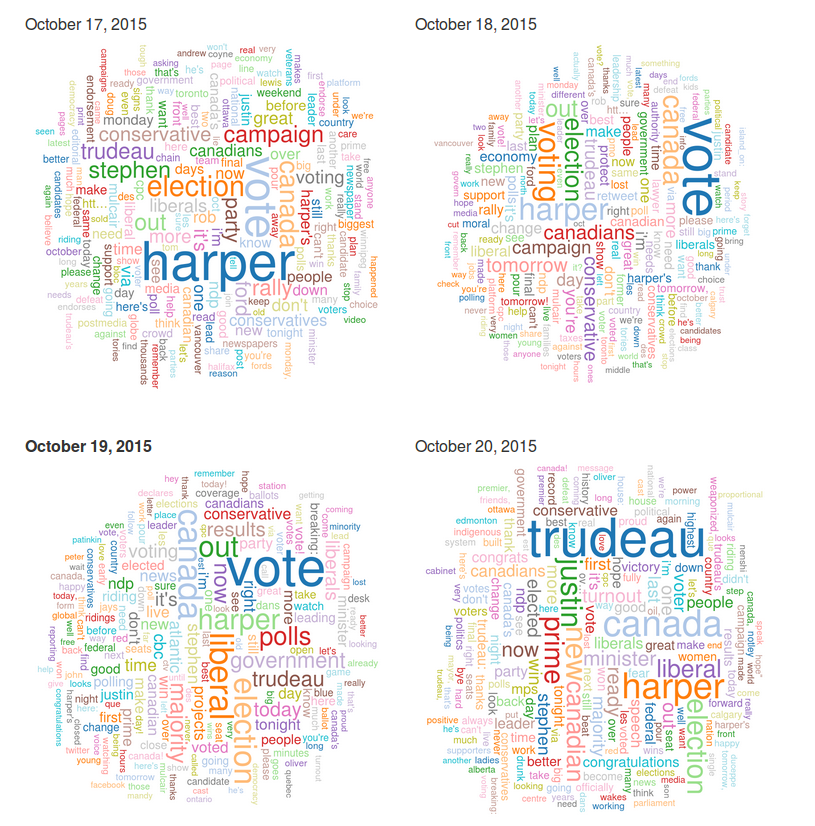

Once broken into dates, we could run further analysis. Built into twarc is the ability to generate word clouds of tweets, using the following command, for example (using the 18 October 2016 data):

$ python ~/git/twarc/utils/wordcloud.py elxn42-tweets-18-oct-2016.json > wordcloud-18-oct-2016.html

While word clouds have considerable limitations, especially in the occlusion of context around a given keyword, the simplicity of the visualization – where the more a word appears the larger it is – can surface overall trends.

The ensuing results can be seen below:

Here we can see the following transition in the tweets:

- 17 October 2015: We see the keyword “Harper” is the most prominent one, as it was throughout much of the election. As the incumbent was a politically polarizing individual, the election was largely a referendum on his leadership.

- 18 October 2015: The day before election day. “Vote” becomes the most prominent, as people want to exhort people to be ready for the polls. No one political party dominates, but the word “conservative” remains the most frequent word.

- 19 October 2015: Election day. We see “Vote” dominate, as well as the word “Liberal.” This was mostly reflecting the widely retweeted announcement of the Liberal Party of Canada’s victory that evening.

- 20 October 2015: The new Prime Minister Trudeau is the topic of the day, as well as his first name: “Justin.”

At a glance, we are seeing a major narrative within the tweets. You can see all of the wordclouds yourself here, or animated here. This could be useful for a researcher wanting an overall birds-eye-view of content, or as a teaser to further investigations.

It also speaks to how researchers could use more sophisticated textual analysis software or programming languages, such as R, Python, Mathematica, or beyond, to extract meaningful information from this soup of knowledge.

Retweets

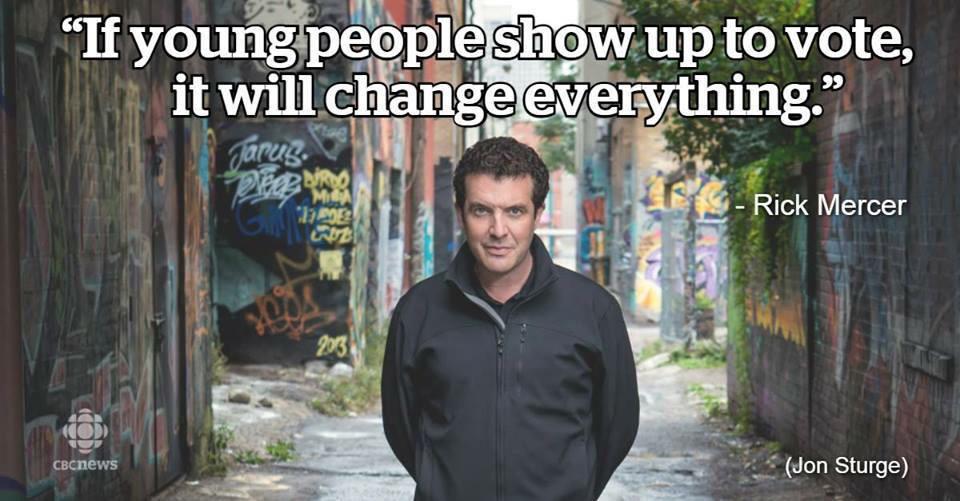

Retweets can tell us quite a bit, mostly around which tweets were collectively deemed to be the most significant: whether because retweeters agreed with them, disagreed with them, or wanted to share in a pivotal moment. For example, the most retweeted tweet was Justin Trudeau and his wife declaring that they were “ready” after winning the election.

The most retweeted tweets can be seen below:

Using retweets.py from twarc utilities:

$ python ~/git/twarc/utils/retweets.py elxn42-tweets-combined-deduplicated.json > elxn42-tweets-retweets.json $ python ~/git/twarc/utils/tweet_urls.py elxn42-tweets-combined-deduplicated.json > elxn42-tweets-retweets.txt

| Retweets | Tweet | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 5483 | https://twitter.com/JustinTrudeau/status/656342399854223360 |

| 2. | 2104 | https://twitter.com/globalnews/status/655983013168336897 |

| 3. | 2104 | https://twitter.com/CBCAlerts/status/656283780152479744 |

| 4. | 1999 | https://twitter.com/CTVNews/status/656283368863223808 |

| 5. | 1808 | https://twitter.com/22_Minutes/status/655902459769004032 |

| 6. | 1760 | https://twitter.com/VancityReynolds/status/656355980997881856 |

| 7. | 1541 | https://twitter.com/pmharper/status/655828288594669569 |

| 8. | 1456 | https://twitter.com/TheAdamChristie/status/656228806118789120 |

| 9. | 1421 | https://twitter.com/west_ender/status/656295500765761537 |

| 10. | 1417 | https://twitter.com/JustinTrudeau/status/655912460101152768 |

Geographic Information

5,370 out of #elxn42 3,918,932 tweets (0.14%) had geographic information associated with them. We were able to determine this by utilizing geo.py and simple command line utilities:

Using geo.py from twarc utilities:

$ python ~/git/twarc/utils/geo.py elxn42-tweets-combined-deduplicated.json > elxn42-tweets-with-geo.json $ cat elxn42-tweets-with-geo.json | wc -1 5370

We were also able to create a geoJSON file of all the tweets with geographic information associated with them. With this geoJSON file, we were then able to map the tweets fairly simply with Leaflet.js.

Using geojson.py from twarc utilities:

$ python ~/git/twarc/utils/geojson.py elxn42-tweets-combined-deduplicated.json > elxn42-tweets.geojson

Using the geoJSON file, we can put them on an interactive map with leaflet.js with some simple HTML and JavaScript boilerplate:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>#elxn42 tweets with leaflet.js</title>

</head>

<body>

<script src="http://ruebot.net/d3.v3.min.js"></script>

<script src="http://ruebot.net/d3.layout.cloud.js"></script>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="http://cdn.leafletjs.com/leaflet-0.7/leaflet.css" />

<script src="http://cdn.leafletjs.com/leaflet-0.7/leaflet.js"></script>

<script src="http://ruebot.net/files/elxn42-tweets.geojson" type="text/javascript"></script>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="http://leaflet.github.io/Leaflet.markercluster/dist/MarkerCluster.css" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="http://leaflet.github.io/Leaflet.markercluster/dist/MarkerCluster.Default.css" />

<script src="http://leaflet.github.io/Leaflet.markercluster/dist/leaflet.markercluster-src.js"></script>

<script src="http://d3js.org/d3.v3.min.js"></script>

<script src="https://raw.github.com/jasondavies/d3-cloud/master/d3.layout.cloud.js"></script>

<div id="map" style="width: 720px; height: 450px;border: 1px solid #ccc;"></div>

<style type="text/css">

.leaflet-popup-content-wrapper .leaflet-popup-content {

width:250px !important;

}

</style>

<script type="text/javascript">

var tiles = L.tileLayer('http://{s}.tile.osm.org/{z}/{x}/{y}.png', {

maxZoom: 18,

attribution: '© <a href="http://osm.org/copyright">OpenStreetMap</a> contributors'

});

var map = L.map('map').addLayer(tiles);

var markers = L.markerClusterGroup();

var geoJsonLayer = L.geoJson(elxn42, {

onEachFeature: function (feature, layer) {

layer.bindPopup('<img src="'+ feature.properties.profile_image_url +'" />

<b>@'+ feature.properties.screen_name +'</b>

<a href="'+ feature.properties.url +'" target="_blank">'+ feature.properties.text +'</a>

');

}

});

markers.addLayer(geoJsonLayer);

map.addLayer(markers);

map.fitBounds(markers.getBounds());

</script>

</html>

GitHub also supports rendering geoJSON files. For example, the geoJSON file above is rendered here with a simple Gist.

Users

We are able to create a list of the unique Twitter usernames in our dataset by using users.py, and additionally sort them by the number of tweets:

Using users.py from twarc utilities:

$ python ~/git/twarc/utils/users.py elxn42-tweets-combined-deduplicated.json > elxn42-tweets-users.txt $ cat elxn42-tweets-users.txt | sort | uniq -c | sort -n > elxn42-tweets-uniq-users.txt $ cat elxn42-tweets-uniq-users.txt | wc -l $ tail elxn42-tweets-uniq-users.txt

Using jq:

$ cat elxn42-tweets-combined-deduplicated.json | jq -r '[.user.name, .user.screen_name] | @csv' | elxn42-tweets-users.txt $ cat elxn42-tweets-users.txt | sort | uniq -c | sort -n > elxn42-tweets-uniq-users.txt $ cat elxn42-tweets-uniq-users.txt | wc -l $ tail elxn42-tweets-uniq-users.txt

From the above, we can see that there are 318,176 unique users in the dataset, and the top 10 accounts were as follows:

| Tweets | Username | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 21423 | DavidMorrison17 |

| 2. | 15527 | P_Wog |

| 3. | 10812 | chuddles11 |

| 4. | 10051 | 444_nal4b |

| 5. | 8871 | JoanneCangal |

| 6. | 8346 | littleshasta |

| 7. | 8316 | MadeInCanada56 |

| 8. | 8114 | LucMatte9 |

| 9. | 7360 | Frazzling |

| 10. | 7019 | StopHarperToday |

Two of the accounts, StopHarperToday and 444_nal4b (a spam account), no longer exist. We discuss this in our deletion section below. The other users all tweeted a large amount on this hashtag, either as individuals or on behalf of organizations.

Hashtags

We were able to create a list of the unique tags using in our dataset by using tags.py. While our original collecting was focused on the #elxn42 hashtag, many tweets use multiple hashtags: tweeting about the New Democratic Party of Canada with #ndp, for example, in addition to the larger #elxn42 tag.

We did so by using tags.py from twarc utilities:

$ python ~/git/twarc/utils/tags.py elxn42-tweets-combined-deduplicated.json > elxn42-tweet-tags.txt $ cat elxn42-tweet-tags.txt | wc -l $ head elxn42-tweet-tags.txt

From the above, we can see that there were 70,112 unique hashtags used. The top 10 hashtags used in the dataset were:

| Tweets | Hashtag | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 3,685,885 | #elxn42 |

| 2. | 1,390,783 | #cdnpoli |

| 3. | 164,339 | #ndp |

| 4. | 139,070 | #cpc |

| 5. | 129,082 | #lpc |

| 6. | 89,303 | #elxn2015 |

| 7. | 68,387 | #polcan |

| 8. | 64,718 | #realchange |

| 9. | 62,282 | #polqc |

| 10. | 61,700 | #globedebate |

URLs

We are able to create a list of the unique URLs tweeted in our dataset by using urls.py, after first unshortening the urls as described in the “Approach to Analysis” section.

We did so by using urls.py from twarc utilities:

$ python ~/git/twarc/utils/urls.py elxn42-tweets-combined-deduplicated-unshortened.json > elxn42-tweets-urls.txt $ cat elxn42-tweets-urls.txt | sort | uniq -c | sort -n > elxn42-tweets-urls-uniq.txt $ cat elxn42-tweets-urls.txt | wc -l $ cat elxn42-tweets-urls-uniq.txt | wc -l $ tail elxn42-tweets-urls-uniq.txt

From the above, we can see that there were 1,988,693 URLs tweeted, representing 50.75% of total tweets, and 334,841 unique URLs tweeted. The top 10 URLs tweeted were as follows:

| Tweets | URL | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 11956 | http://www.cbc.ca/includes/federalelection/dashboard/index.html |

| 2. | 9712 | http://www.conservative.ca/ |

| 3. | 4562 | http://www.votetogether.ca/ |

| 4. | 3983 | http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/macleans-debate-leaders-2015-1.3182000 |

| 5. | 3926 | http://www.elections.ca/Scripts/vis/FindED?L=e&QID=-1&PAGEID=20 |

| 6. | 3104 | http://www.elections.ca/home.aspx |

| 7. | 2812 | http://www.theglobeandmail.com/try-it-now/?articleId=26875323 |

| 8. | 2808 | https://www.facebook.com/abu.nawaf.581/posts/10206977713713332?pnref=stor |

| 9. | 2757 | http://dont-be-a-fucking-idiot.ca/ |

| 10. | 2707 | https://www.mypayingads.com/index.php?ref=51826 |

We were also curious how many domains were tweeted. This required two steps. First, taking a text file (see elxn42-tweets-urls.txt in our dataset) of the URL list and then extracting only the domain:

#!/bin/bash

while read p; do

echo $p | awk -F/ '{print $3}'

done < elxn42-tweets-urls-fixed.txt > domains-all.txt

And then subsequently normalizing by removing sub-domains, so that m.youtube.com and youtube.com were both simply recorded as youtube.com.

#!/bin/bash

while read l; do

(sed 's/.*\.\(.*\..*\)/\1/' <<< ${l%/*})

done < domains-all.txt > normalized-domains-all.txt

And generating sorted frequency lists with:

sort normalized-domains-all.txt | uniq -c | sort -nr > normalized-domains-all-sorted.txt

The top 10 domains that were tweeted were as follows:

| Tweets | Domain | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 615421 | twitter.com |

| 2. | 143941 | cbc.ca |

| 3. | 66886 | youtube.com |

| 4. | 66758 | huffingtonpost.ca |

| 5. | 63401 | theglobeandmail.com |

| 6. | 53051 | thestar.com |

| 7. | 49295 | ctvnews.ca |

| 8. | 46488 | globalnews.ca |

| 9. | 39989 | twimg.com |

| 10. | 35280 | macleans.ca |

From this we can get a sense of how social media shapes what people share, although legacy media was surprisingly well-represented in the Canadian context: the Canada Broadcast Corporation (especially their election day dashboard), the two highest-circulation newspapers the Globe and Mail and Toronto Star, and popular television networks CTV and Global News. While the Huffington Post‘s Canadian edition made an appearance, we were surprised by the degree to which traditional media dominated.

Embedded Images

We are able to create a list of images tweeted in our dataset by using image_urls.py.

Using image_urls.py from twarc utilities:

$ python ~/git/twarc/utils/image_urls.py elxn42-tweets-deduped.json > elxn42-tweets-images.txt $ cat elxn42-tweets-images.txt | sort | uniq -c | sort -n > elxn42-tweets-images-uniq.txt $ cat elxn42-tweets-images.txt | wc -l $ cat elxn42-tweets-images-uniq.txt | wc -l $ tail elxn42-tweets-images-uniq.txt

Using jq:

$ cat elxn42-tweets-deduped.json | jq -r '.entities | select(.media != null) | .media[].media_url_https' | cat > elxn42-tweets-images.txt $ cat elxn42-tweets-images.txt | sort | uniq -c | sort -n > elxn42-tweets-images-uniq.txt $ cat elxn42-tweets-images.txt | wc -l $ cat elxn42-tweets-images-uniq.txt | wc -l $ tail elxn42-tweets-images-uniq.txt

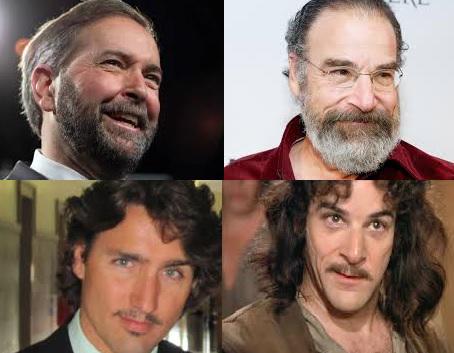

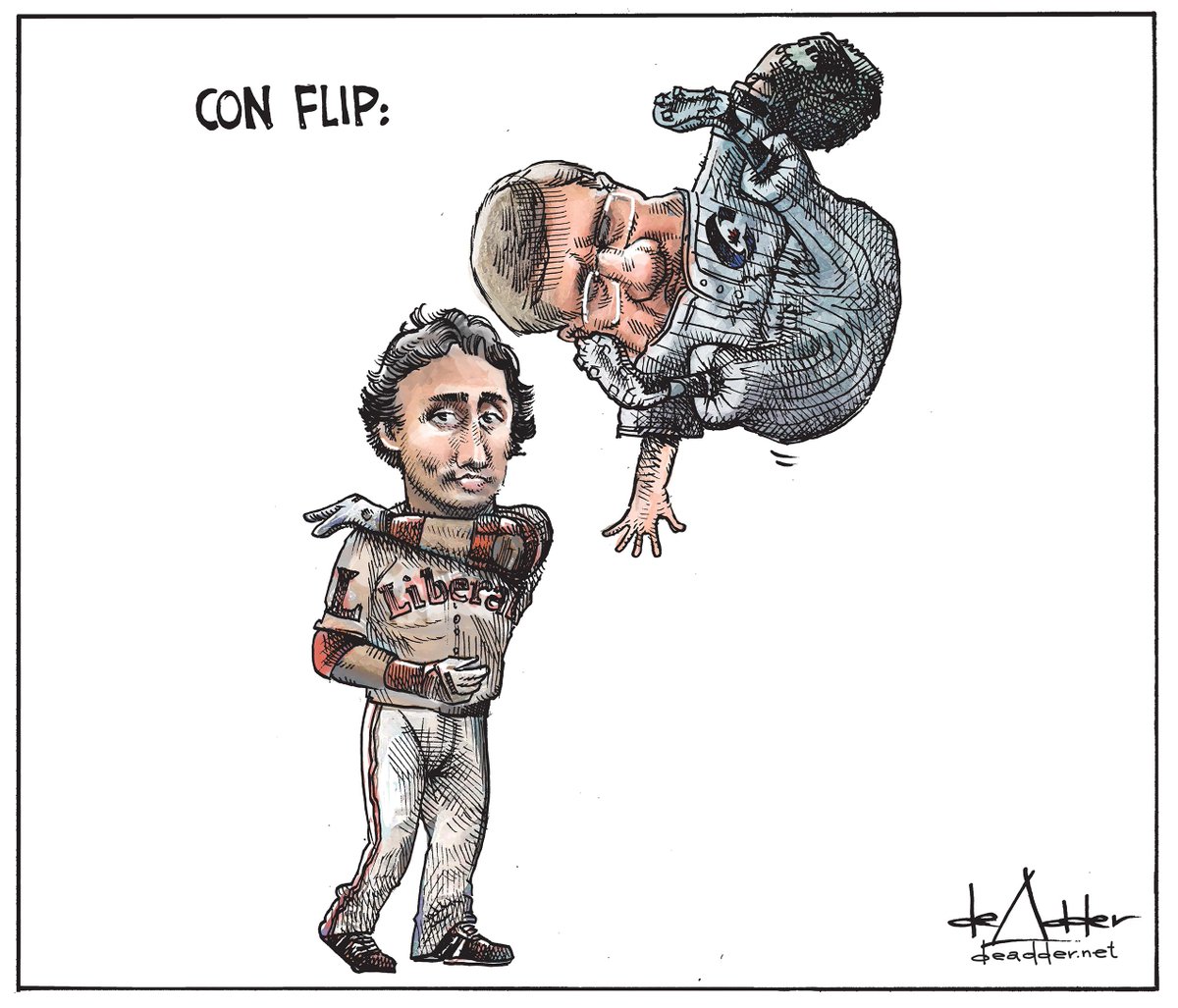

From the above, we can see that there were 1,203,867 total images tweets, representing 30.72% of total tweets, and 176,513 unique images. The top 10 images tweeted were as follows:

| Tweets | Image | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 5111 |  |

| 2. | 2247 |  |

| 3. | 1975 |  |

| 4. | 1968 |  |

| 5. | 1895 |  |

| 6. | 1478 |  |

| 7. | 1376 |  |

| 8. | 1357 |  |

| 9. | 1346 |  |

| 10. | 1206 |  |

Deleted Tweets

As mentioned above, twarc has a mode called “hydrate”. Hydrate allows a user to a take a set of tweet ids — in this case you can use the data set we are working with here — and hydrate the tweets ids with the full tweet from the Twitter API. This process can be slow since, “Twitter limits users to 180 API requests every 15 minutes. Each request can hydrate (Twitter’s term for turning tweet ids into tweet objects) at a rate of up to 100 tweet IDs using the statuses/lookup REST API call. So 80 requests * 100 tweets = 18,000 tweets/15 min = 72,000 tweets/hour.” (Summers, 2015) In our case, we began hydrating on November 21, and finished on November 23. The process took a little over 39 hours. In the end, we had a total of 2,832,270 tweets. Which means that 207,534 tweets deleted, giving us a 7.33% tweet churn.

The Twitter Developer Agreement & Policy prevents us from going into much detail on the deleted users, but several significant users were deleted. One, StopHarperToday, no longer exists as of writing. And another major account, 444_nal4b, appears to be a spammer account that extensively tweeted on the #elxn42 hashtag. While Twitter’s user experience is arguably enhanced by the loss of spam tweets, they are an essential part of the Twitter experience and it is worth nothing that they may be significantly reduced in rehydrated Twitter databases. Future historians may have difficulty studying the online advertisements – annoying as they can be – of our day, unless the original data is deposited somewhere where it can be studied (the Library of Congress, perhaps?).

But this, as noted in our reflection on ethics, is one of the key components of working responsibly with Twitter. As Ed Summers (2015a) has put it:

But if you squint right, Twitter is taking an ethical position for their publishers to be able to remove their data: to exercise their right to be forgotten, allowing them to remove a teensy bit of what Maciej Ceg?owski calls informational toxic waste.

People may be deleting their tweets because they were spam, or inflammatory, or something they regretted, especially in the aftermath of a heated election. Summers (2015b) and Ruest noted much the same with tweets in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo massacre. Ultimately, archives are always full of large gaps and omissions: at least in this one we know that people in many cases could make their own informed decision to be removed.

Integrating Twitter Archiving with Web Archiving

There are also fruitful opportunities for integrating this form of Twitter archiving and analysis with other approaches to web archiving. Our team has a complementary undertaking, the WebArchives.ca portal, which enables citizen access to large Canadian political web archives.

The Canadian Political Parties and Political Interest Groups (CPP) collection is a key example of these sorts of collections. The CPP collection is of national interest in Canada, covering some fifty groups ranging from major and minor Canadian political parties to an assortment of political interest groups. Collected quarterly, and occasionally more frequently during federal elections, it is an invaluable record of public and political life. In the lead up to the 2015 federal election, we received almost 30,000 page views and some 3,000 individual distinct users. It also received significant media attention in the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, including on several national programs.

This collection, however, has a significant downside: its limited seed list. Of the 263,708 unique URLs, we checked each against the list of fifty domains to see which of the URLs tweeted would have been included in the CPP collection. 46,778, or 17.7%, were part of the fifty top-level domains. On the #elxn42 hashtag then, 82.3% of URLs that were tweeted would not have been included in the formal CPP collection.

The domains shared also affected their permanent archiving within the global web archive. By comparing this list of unique URLs to the Internet Archive’s CDX Availability API, which takes a user-provided URL and determines whether there is an archived, accessible copy in the main Wayback Machine, we found that of the 334,841 unique URLs, only 20.34% or 68,112 existed at all in the Wayback Machine. Of those 68,112 URLs, only 33,685 had been archived relatively recently, between August and December 2015. This is largely due to the domains that are largely excluded from the Wayback Machine: Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, for example.

This speaks to the importance of social media crawls. 334,841 links were shared by everyday people during the election, and only roughly one in five would appear in the global Wayback Machine. Twitter archiving is a useful complement to a broader web archiving strategy. Social media is an essential primary source for gathering and aggregating content that matters to people, for both contemporary analysis and for the future historical record. We currently have a separate paper comparing this analysis in detail as a method of web archive seed list generation, building on previous International Internet Preservation Consortium (IIPC)-funded work such as TwitterVane. (Milligan et al, 2016)

Conclusion

This article has outlined a light-weight and open-source method of collecting and analyzing Twitter events. The case study of the 2015 Canadian federal election hashtag, #elxn42, is roughly analogous to other medium-scale, longitudinal events: it lacked the severe spikes and pitfalls of an event such as the Paris shootings or an American election (in which case a commercial approach would be necessary for full scoping). Yet it is a perfect fit for many events of interest to libraries, archives, and special collections.

Beginning by identifying a hashtag of interest, twarc can be used to assemble a full dataset of tweets. twarc-report, twarc‘s utilities, and other tools discussed here can all give users a rough sense of what happened within the collection. These distant reading approaches could help isolate particular days, users, or popular tweets for researchers to study. They could not read all four million tweets, but they could use these tools to find the right ones to investigate further. While Twitter’s Developer Agreement & Policy prevents the wholescale sharing of the collected data itself, rosters of Tweet IDs can be easily shared using institutional repositories or other sharing platforms, allowing other users to “rehydrate” their own tweets. While this has the downside of removing tweets deleted until the moment of rehydration, this allows one to continually monitor “churn” within a collection.

Others may be interested in using this project to either continue their own work on the #elxn42 corpus – political scientists studying an election, for example – or as an illustrative model for other unfolding events. For those interested in using the tweet data, it can be downloaded here.

In an era where web archiving and Twitter collection can be seen as expensive luxuries, this article shows how, for a relatively small investment of computing power, bandwidth, and storage, people can create and analyze their own Twitter archives. While aimed at historians and librarians, the open-source and free model outlined here really does open up the realm of citizen scholars being able to do their own work along these lines. As social movements unfold, both those who study events as well as those who are participating are able to collect their own archives. We hope that our #elxn42 experience can serve as an illustrative model to all of these disparate groups.

Acknowledgements

We’d like to graciously thank the support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, which has supported this work with an Insight Grant (435-2015-0011), as well as Russell White and Tom Smyth from Library and Archives Canada for collecting and sharing #elnx42 tweets, and Ed Summers for creating twarc. Thanks as well to Jason Colditz, Zack Macdonald, Shawn Graham, Ed Summers, Peter Murray, John Fink, and Peter Binkley.

References

- Bady, A., #NotAllPublic, Heartburn, Twitter, 10 June 2014, http://thenewinquiry.com/blogs/zunguzungu/notallpublic-heartburn-twitter/, last accessed 16 June 2015

- Binkley, Peter, twarc-report README.md, https://github.com/pbinkley/twarc-report/blob/master/README.md, last accessed 24 Apr 2015

- Driscoll, K. and S. Walker, Big Data, Big Questions| Working Within a Black Box: Transparency in the Collection and Production of Big Twitter Data, International Journal of Communication, vol. 8, p. 20, Jun. 2014.

- Gleick, James, The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood, 2012.

- IBM Research, What is Big Data? http://www-01.ibm.com/software/data/bigdata/what-is-big-data.html, 2016.

- Library and Archives Canada, #elxn42 tweets (42nd Canadian Federal Election), hdl:10864/11310 V3 [Version], 2015

- Kim, Dorothy and Eunsong Kim, The #TwitterEthics Manifesto, 7 April 2014, https://modelviewculture.com/pieces/the-twitterethics-manifesto.

- Milligan, Ian; Nick Ruest and Jimmy Lin, “Content Selection and Curation for Web Archiving: The Gatekeepers vs. the Masses,” Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE Joint Conference on Digital Libraries 2016. Forthcoming.

- O’Neil, Lauren, University’s ‘Black Twitter’ study generates controversy, 4 September 2014, http://www.cbc.ca/newsblogs/yourcommunity/2014/09/universitys-black-twitter-study-generates-controversy.html.

- Ruest, Nick, #elxn42 tweets, http://hdl.handle.net/10864/11270 V2 [Version], 2015.

- Ruest, Nick; Library and Archives Canada, 2015-12-07, #elxn42 tweets (42nd Canadian Federal Election), hdl:10864/11311 V2 [Version], 2015

- Sharma, Seemantani; Vakil Smallen; and Daniel Chudnov, “Social Feed Manager,” presented at Web Archives 2015: Capture, Curate, Analyze, Ann Arbor, MI, 13 November 2015. http://www.lib.umich.edu/webarchivesconference/webarchives-schedule

- Summers, Ed; Hugo van Kemenade; Peter Binkley; Nick Ruest; recrm; Stefano Costa; Eric Phetteplace; et al. Twarc: v0.3.4. Zenodo, 2015. doi:10.5281/zenodo.31919.

- Summers, Ed, On Forgetting and hydration, https://medium.com/on-archivy/on-forgetting-e01a2b95272, 2015a.

- Summers, Ed, Tweets and Deletes, 14 April 2015, http://inkdroid.org/2015/04/14/tweets-and-deletes/, 2015b.

About the Authors

Nick Ruest is the Digital Assets Librarian at York University, and co-Principal Investigator of the SSHRC grant “A Longitudinal Analysis of the Canadian World Wide Web as a Historical Resource, 1996-2014“.

At York University, he oversees the development of data curation, asset management and preservation initiatives, along with creating and implementing systems that support the capture, description, delivery, and preservation of digital objects having significant content of enduring value. He is also active in the Islandora and Fedora communities, serving as Project Director for the Islandora CLAW project, member of the Islandora Foundation’s Roadmap Committee and Board of Directors, and contributes code to the project. In the past he has served as the Release Manager for Islandora, the moderator for the OCUL Digital Curation Community, the President of the Ontario Library and Technology Association, and President of McMaster University Academic Librarians’ Association.

Ian Milligan is an assistant professor of digital and Canadian history at the University of Waterloo. He is also principal investigator of the Web Archives for Historical Research group. He serves as a co-editor of the Programming Historian. His favourite service roles at Waterloo involve working with the University of Waterloo Library and he also serves on Library and Archives Canada‘s Acqusitions Advisory Committee.

His new book, Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope (co-authored with Shawn Graham and Scott Weingart), appeared in late 2015. He has published on Web and digital archives in Histoire Sociale/Social History, the Canadian Historical Review, the International Journal of Arts and Humanities Computing, and the Journal of the Canadian Historical Association. His 2013 article “Mining the Internet Graveyard” won the Journal of the Canadian Historical Association’s best article award that year. These complement publications in other Canadian academic journals and a 2014 monograph with the University of British Columbia Press entitled Rebel Youth: 1960s Labour Unrest, Young Workers, and New Leftists in English Canada.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply