by Tara M. Wood and Cate Kompare

Introduction

A full website redesign is often the most traumatic approach for both users and stakeholders, which is why many usability experts advocate for an iterative enhancement approach over complete redesigns.[1] [2] [3] The scope of the project can balloon out of control as internal stakeholders put too many demands on the “final” product and frequent users that have learned your old site have to struggle to learn the new one. However, Loranger describes cases in which this aggressive approach is necessary.[4] For sites with a severely outdated platform, convoluted information architecture, and/or benchmarking measures that reveal the site to be far behind the competition, a full redesign can be the most effective and efficient approach.

In the Spring of 2015, the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) Library had a website that had not been significantly updated since 2009, on a platform that was no longer supported, and an information architecture that had grown organically over the years, full of content that had not been regularly maintained. The Library engaged Pixo, a design and technology firm, to redesign library.uic.edu in an unusually collaborative client/vendor relationship. Pixo team members worked hand-in-hand with librarians and staff through all phases of the redesign process, including research, design, and development, and incorporated participatory design techniques to manage risks and expectations, both within the core design and development team and among the wider group of Library stakeholders.[5]

Participatory Design and Libraries

Participatory design seeks to bring stakeholders and users into the design process through a variety of research and co-design activities.[6] These activities uncover the tacit knowledge and expectations that users bring to technologies, empowering people that may not have a background in design or technology to bring their expertise to final product. Key components of the participatory design methodology include:

- An iterative design and development process that includes users and stakeholders throughout;

- Project goals and criteria that are collaboratively developed between design researchers and stakeholders;

- Representation of a variety of perspectives and/or clear communication to different user groups when all users and stakeholders cannot actively participate in the project.[7]

Participatory design encompasses a wide variety of techniques. Sanders, Brandt, and Binder define a framework for selecting participatory design techniques based on the form of activities, their purpose, and their context — when, where, and with whom the activities take place.[8] The three forms they discuss are “making tangible things,” which includes visual maps and collages; “talking, telling, and explaining”, which includes card sorting and diary activities; and “acting, enacting, and playing,” which includes games and improvisation activities.

Participatory design activities used in libraries include:

- On-the-fly and scheduled interviews to map use of library spaces;[9]

- Creating low-fidelity prototypes through participatory design workshops with users;[10] [11]

- Visual narrative inquiry, in which users sketch their research processes;[12]

- Sketching new web site pages and marking up paper versions of existing pages;[13] [14]

- Drawing and verbal participatory design activities around restructuring library work spaces.[15]

Even though the primary objective of participatory design is to bring the end-user of a system into the process of designing it, these techniques can also be used to bring internal stakeholders into the process of conducting and interpreting the results of end-user research.[16] Colby College used co-viewing sessions to collaboratively share and interpret video recorded interviews conducted with faculty and students, bringing both librarians and members of the College’s Academic Information Technology Services into the process of making design decisions.[17] This “broader participation” approach builds consensus, understanding about the end-users, and enthusiasm for the project.

Of course, complete consensus is not realistic and including many stakeholders in any type of project carries its own risks. Participatory design is not a replacement for a clear, transparent digital governance framework, but it can be a piece of that framework. Welchman emphasizes that “a digital governance framework does not specify a production process. It does not articulate a content strategy, information architecture, or whether or not you work in an agile or waterfall development environment. What a digital governance framework does is specify who has the authority to make those decisions. This explicit separation of production processes from decision-making authority for standards is what gives the framework its power”.[18] In short, a governance strategy ensures someone is ultimately responsible for ensuring decisions get made, and participatory design is one possible process for making those decisions.

Participatory Design at the UIC Libraries

Led by the design team, over 60 Library stakeholders participated in various stages and activities of the redesign of the UIC Library website. For this project, stakeholders included librarians, staff, and administrators. In addition, the Web Services Librarian more widely communicated findings and activities through regular visits to department and committee meetings and a staff blog.

Developing shared design goals

Prioritization Matrix

In a large redesign project, choosing what features and sites to address first can be contentious. To develop priorities participatively, Pixo developed a prioritization matrix (Figure 1.) and worked through it with the UIC Library’s Web Advisory Group.

| Criteria | Site/Platform 1 | Site/Platform 2 | Site/Platform 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is this service high traffic? | ||||

| Are students the primary audience for this service? | ||||

| Is the platform flexible enough to make changes? | ||||

| Does maintaining this platform align with the library’s goals and mission? | ||||

| Do information goals for testing this feature align with usability testing outcomes? | ||||

| Has usability testing already been done? |

Through this activity, the Library chose to focus on the main website, research guides, and our Summon implementation in initial usability testing.

Stakeholder interviews

To initiate the process of defining project goals and criteria, the Web Advisory Group conducted a series of semi-structured, small group interviews with 42 librarians and library staff from across all departments and locations (Appendix A: Interview Questions). Some interviewees were recruited to provide a representative sample, but all librarians and library staff were invited to participate. These interviews explored what stakeholders hoped that the new website would provide, their challenges with the current site, and what they could bring to the redesign process.

The result of these interviews was a Redesign Strategy (Appendix B: Redesign Strategy), which served as both a governance framework and as an outline of the participatory design methodology. The strategy included:

- Collaboratively developed shared goals, design principles, and project priorities;

- A definition of different stakeholder groups, their roles in an iterative process, and how a variety of perspectives would be incorporated;

- An agreed-upon scope of work;

- Project milestones and the groups responsible at each milestone for participation, decision-making and communication efforts.

To build consensus, the Redesign Strategy was shared in meetings, through the staff intranet, and through the library staff blog. At many points during the redesign, the design team was able to turn to the document to keep the process moving forward and ensure we were including the right groups at the right points in the project.

Voice and Tone Workshops

A key component of the Redesign Strategy was an improved content strategy. Though only a handful of staff participate as content authors, a wider group of library staff participated in defining the voice and tone of content. The Content Strategist at Pixo developed a Voice and Tone Workshop (Appendix C: Voice and Tone Worksheet), which the Web Services Librarian moderated with library staff and content authors. Activities in this workshop included:

- Blank, but not blank: Stakeholders chose three adjectives to describe the “personality” of the Library, then clarified those terms by filling in the statement”_______ , but not _______ “, i.e. “forward-thinking, but not impulsive”.

- Personality spectrum: Participants chose where the Library falls on a scale of certain characteristics, for example, between “accessible to all” and “elite”.

This workshop provided a stage for conversation around how librarians and library staff want to communicate to and be perceived by our users. Some stakeholders favored a more scholarly tone, while others favored a friendly, more informal tone. Through moderated conversation, stakeholders were able to come to a consensus on a friendly, unified tone, and content authors had a more nuanced view of how they they should approach the content.

Conducting UX research with students

Students were the highest priority audience for the site redesign, and the design team brought library stakeholders into the design, implementation, and evaluation of UX research with students.

Usability Pop-Up Lab

To prepare Library stakeholders for participation in usability testing with students, the UX designers at Pixo conducted a usability pop-up lab. Participants learned how and why to conduct usability tests, and they participated in group activities that simulated taking notes and moderating usability tests. Following the pop-up lab, Library stakeholders participated in the design of testing scripts, and as notetakers and moderators in usability tests of the current website, wireframes, and the beta version of the new site. These stakeholders were then able to more widely share the findings of usability testing with committees and departments across the library.

Instrument Brainstorming and Design Sessions

The design team also recruited Library staff to design and participate in participatory design activities with students. The design team first met with two reference librarians — one undergraduate experience librarian and one health sciences librarian — to develop research instruments. The group reviewed several types of participatory design activities from Universal Methods of Design and sketched out the following activities and instruments:[19]

- Fill-in-the-blank: We invited students to complete the following phrases on some printouts:

- “I wish the Library website was more like _______,”

- “When doing assignments for _______, I use _______, _______, and _______ from the Library website,”

- “I’m really frustrated that the Library doesn’t have _______ and _______ online.”

- ?/+: At the top of a large piece of paper, we drew a delta symbol and plus sign, instructing students to list what they’d change about the Library website as well as what is working well with the Library website.

- Love letters & break-up letters to the Library: Students were provided with some “stationery” to write to the Library, saying what they loved or why they would want to end their relationship with the Library.

Library stakeholders across all five library locations then participated in implementing these activities, moderating activity areas, recruiting participants on-the-fly, and conducting impromptu follow-up interviews about student responses.

Later during the wireframing process, the Library’s Discovery Systems Advisory Group (DSAG) collaboratively developed a worksheet activity centered around the home page search. This activity consisted of a two sided worksheet:

- “X/O” activity: Participants could cross out (“X”) items on a screenshot that they would not use, and circle (“O”) items that they would use.

- Search box sketching activity: Participants sketched their ideal search box

The group distributed the worksheets, processed the results, and developed a final search box design.

Processing UX research results

To process the results of student research activities, the design team worked with a representative group of Library stakeholders from different public services areas. This group collaboratively analyzed findings through a structured session including several activities:

- Review of the findings at a high level through a presentation from the UX Designer at Pixo;

- Group discussion and development of a changeability matrix to determine what challenges we could realistically address in this initial redesign, based on budget and timeline restrictions, along with limitations around proprietary tools;

- Group discussion and sketching of an idealized novice research flow, based around the question: “If the Library web presence was perfect, how would a freshman find the information they needed to complete an assignment?”;

- Individual sketching of the ideal Library homepage, and then a group discussion of the similar and different elements.

This series of activities guided the group from reflection to ideation, and it was useful in managing expectations while generating a shared vision of what the end product could be.

Prototyping

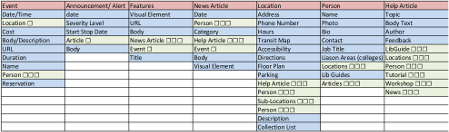

The design team started the prototyping process with OOUX or Object Oriented UX, a collaborative analysis technique that is effective for planning the underlying information architecture, content model, and software architecture.[20] The process is inspired by the concept of Object Oriented Programming, meaning that the site is a collection of connected objects that users act on, rather than a series of static pages. A broad cross-section of the team, including librarians, developers from the Library and Pixo, and Pixo’s project manager and UX designer gathered in a conference room with post-it notes and sharpies. Together, they discussed and defined the core content, metadata, connections between content, and calls to action for the new site. This process allowed the team to create a shared language and expose misunderstandings long before development began. The outcome of this session — which was held before any development began — closely reflects the way content is structured and displayed across the live site.

Figure 2.

Pink post-its represent core content types, blue represent metadata, and green represent connections between metadata and content.

Figure 3.

The post-it notes were translated to a spreadsheet that was updated and referenced throughout the design process.

The content model that emerged from the OOUX process was the starting point for the content management system and the wireframes. The pink post-its became content types in the content management system, blue post-its became metadata fields, and green pos- its became shared fields across content types. Cate Kompare, the UX Designer at Pixo, developed an initial draft of the wireframes, which Tara Wood, the Web Services Librarian at UIC, refined based on input from usability testing, the X/O activity, search box sketching, and librarian and staff input. Developers at UIC built the content management system in WordPress, in collaboration with the developers at Pixo, who worked on the decoupled front end and infrastructure.[21]

Reflections on the Participatory Process

Successes

Several practical benefits came out of using a participatory approach.

Shared vision and vocabulary

First, we avoided confusion, delays, and siloed decision-making through the OOUX workshop. The implementation team included developers and designers from two organizations that did not reside in the same city and had never worked together before. A collaborative development approach ensured the Library’s in-house team would be prepared to maintain the site over the long term, but it also presented short-term risks. Team members could have duplicated efforts, made assumptions that cost time and money, and built out conflicting components of the site. The OOUX model provided a way for developers, designers, and stakeholders to bridge different roles, develop a content model that reflected the perspectives of many disciplines, and build a shared vocabulary to talk about the site structure moving forward. This single vision and shared vocabulary strengthened communication within the implementation team, so they were able to avoid misunderstandings and launch a complex project on time.

Better communication with stakeholders

Second, we reduced frustration and improved communication with Library stakeholders by coming to agreement at the start of the project about who would be involved at what steps. In early stakeholder interviews, many interviewees indicated their frustration around not knowing who was responsible for certain decisions, or who to go to for help or feedback. The same interviews revealed communications silos that needed to be overcome during the project. The Redesign Strategy was developed out of stakeholder interviews, and it defined how, when, and to what extent different groups would be involved in the project. Stakeholders were able to clearly see and agree upon what committees were responsible for decision making in certain areas of the project and the design team was able to ensure they did not leave out someone that should be involved.

For example, all staff had the opportunity to review mockups through a staff survey; the Library’s Steering Committee, a group of department heads and supervisors, had final review of the mockups; and the committee chair was responsible for collating feedback and making the final recommendation. Many people had a voice in the final version, but because roles were clearly defined, no one person could bring the project to a halt over minor quibbles about small details. The design team also knew far in advance that we needed to develop the staff survey, distribute it through email and the staff blog, and schedule a visit to the monthly Steering Committee meetings to present the feedback and mockups. We were better able to plan our communications and space them out appropriately to avoid a communications overload.

Increased user advocacy

Finally, since participation was so broad, librarians and teammates were all empowered to answer the question, “what would help the user?” and answer based on research rather than anecdotes or speculation. Nielsen argues that involving stakeholders in usability testing sessions develops empathy with users, makes the results more memorable and credible, and increases buy-in to the findings and decisions made with those findings.[22] At UIC, we also saw increased credibility and buy-in with the stakeholders that did not directly participate in student research activities. The librarians and staff that participated in usability tests served as champions for the user in their departments and committees. They advocated for the results of student research, the design decisions made, and shaped feedback from their colleagues into actionable insights, acting as translators between different groups of stakeholders.

For example, health sciences librarians wanted to include a PubMed search on the homepage, but usability testing with health sciences students showed that students use a broad range of resources and did not feel PubMed should be emphasized over others. A health sciences librarian participated in those usability tests and the design of the home page search, and she lead discussions with colleagues about the results. As a result of those discussions, the home page search launched with a link to a small group of popular resources including, but not limited to, PubMed. Arguably, this improved the site for users by reducing visual clutter and cognitive load, while providing a more balanced view of the resources available.

Challenges

Of course, no project is without limitations or challenges.

Time

The biggest challenge of conducting a participatory design process is the investment of time on behalf of the design team and the stakeholders. At UIC, we spent one year conducting research activities before development began, followed by additional usability activities during the development phase. The design team relied on stakeholders to volunteer time in their busy schedules, and we tried to balance the time commitment through opportunities for varying levels of involvement, from the hour-long Voice and Tone Workshop to several hours designing and participating in usability tests. A disadvantage of this approach is that few participants had the opportunity to see how the full spectrum of participatory and research activities fit together.

Remote participation

UIC also has five libraries spread out over four locations, so we had an additional challenge of deciding what activities could be conducted remotely and what needed to happen in person.

The design team determined that the OOUX workshop needed to happen in person, so the team from Pixo traveled from Urbana to meet with Library stakeholders in Chicago. We could have used an online tool, but the design team felt that the consensus-building aspect of the activity would have been diminished, compared to in-person conversation and interaction with physical space (a big wall of post-its). In addition, the Web Services Librarian traveled to all five libraries to conduct participatory research activities with students, in collaboration with the librarians and staff at each location. While travel took significantly more time and effort, it allowed stakeholders and students at the remote locations to be included in, and to better understand, the participatory design process.

Stakeholder interviews and the Voice and Tone Workshop, for example, were more easily conducted over the phone and screen sharing software. However, remote group activities can be difficult, as people present in the room can talk over those that are on the phone; a moderator is essential to make space for the remote participants to enter the conversation.

Mockups and wireframes

Engaging stakeholders with wireframes and mockups was also a challenge. While Library stakeholders were more hands-on in earlier prototyping activities, including sketching and the OOUX workshop, these more refined prototypes were developed between the core design and development team at Pixo and the UIC Library, and other Library stakeholders participated with mockups and wireframes in a more conventional feedback process. Many stakeholders did not grasp information architecture and navigation elements in the wireframes and mockups until seeing them in the beta version of the site. The authors speculate that conducting additional rounds of the OOUX workshop with a wider group of stakeholders may have been helpful in building a better understanding of the information architecture presented in the wireframes. In addition, activities built around providing better feedback or heuristic evaluation could have better prepared stakeholders to engage with and see the relationships between the interactive, clickable wireframes and the static mockups.

Conclusions

Using participatory design methods did not eliminate all conflicts in the UIC Library website redesign, but these methods did help the authors to anticipate challenges, develop a shared understanding with stakeholders, and keep the project on track. The redesign launched on time, ready for the start of the fall semester, not in spite of including so many people in the process, but because the whole organization had a stake in getting the new site ready for launch. The participatory process will continue at the UIC Library as we iterate and improve upon both the site and participatory design techniques we use to define goals and design solutions that better serve our students.

References

[1] Nielsen, Jakob. 2009. “Fresh vs. Familiar: How Aggressively to Redesign.” https://www.nngroup.com/articles/fresh-vs-familiar-aggressive-redesign/.

[2] Rosenfeld, Louis. 2012. “Stop Redesigning And Start Tuning Your Site Instead.” Smashing Magazine, May. https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2012/05/stop-redesigning-start-tuning-your-site/.

[3] Spool, Jared. 2013. “Extraordinarily Radical Redesign Strategies.” UX Articles by UIE. March 20. https://articles.uie.com/radical_redesign/.

[4] Loranger, Hoa. 2015. “Radical Redesign or Incremental Change?” Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/radical-incremental-redesign/.

[5] Kompare, Cate. “Check this out: UIC Library’s New Site!” Café Pixo. https://medium.com/cafe-pixo/check-this-out-uic-librarys-new-site-c6d66f162ece#.bikeylfk9

[6] [19] Martin, Bella, and Bruce Hanington. 2012. Universal Methods of Design?: 100 Ways to Research Complex Problems, Develop Innovative Ideas, and Design Effective Solutions. Osceola, US: Rockport Publishers.

[7] Spinuzzi, Clay. 2005. “The Methodology of Participatory Design.” Technical Communication 52 (2): 163–74.

[8] Sanders, Elizabeth B.-N., Eva Brandt, and Thomas Binder. 2010. “A Framework for Organizing the Tools and Techniques of Participatory Design.” In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference.

[9] Werner, Mark, and Mark Mabbett. 2014. “Improving Norlin Commons: An iPad + Evernote Approach.” In Participatory Design in Academic Libraries: New Reports and Findings, 34–48. Council on Library and Information Resources.

[10] Guo, Yan Ru, and Dion Hoe-Lian Goh. 2016. “Library Escape: User-Centered Design of an Information Literacy Game.” Library Quarterly 86 (3): 330–55.

[11] Garritano, Jeremy R., and Jane Yatcilla. 2014. “Participatory Design of the Active Learning Center: A Combined Classroom and Library Building.” In Participatory Design in Academic Libraries: New Reports and Findings, 88–99. Council on Library and Information Resources.

[12] Mattern, Eleanor, Wei Jeng, Daqing He, Liz Lyon, and Aaron Brenner. 2015. “Using Participatory Design and Visual Narrative Inquiry to Investigate Researchers’ Data Challenges and Recommendations for Library Research Data Services.” Program: Electronic Library & Information Systems 49 (4): 408–23.

[13] Cardinal, Susan K. 2014. “A Recipe for Participatory Design of Course Pages.” In Participatory Design in Academic Libraries: New Reports and Findings, 21–33. Council on Library and Information Resources.

[14] Foster, Nancy Fried, Nora Dimmock, and Alison Bersani. 2008. “Participatory Design of Websites with Web Design Workshops.” The Code4Lib Journal, no. 2 (March). http://journal.code4lib.org/articles/53.

[15] Swindells, Geoffrey, and Marianne Ryan. 2014. “Library Practice as Participatory Design.” In Participatory Design in Academic Libraries: New Reports and Findings, 100–108. Council on Library and Information Resources.

[16] Schuler, Douglas, and Aki Namioka, eds. 1993. Participatory Design: Principles and Practices. Hillsdale, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates.

[17] Pukkila, Marilyn R., and Ellen L. Freeman. 2014. “Co-Viewing: Creating Broader Participation Through Ethnographic Library Research.” In Participatory Design in Academic Libraries: New Reports and Findings, 49–54. Council on Library and Information Resources.

[18] Welchman, Lisa. 2015. Managing Chaos: Digital Governance by Design. Brooklyn, New York: Rosenfeld Media (O’Reilly).

[20] Voychehovski, Sophia. 2016. “Object-Oriented UX.” Accessed November 20. http://alistapart.com/article/object-oriented-ux.

[21] Pixo. “Outpost: A PHP Framework for Decoupled Websites.” http://getoutpost.org/

[22] Nielsen, Jakob. 2010. “Involving Stakeholders in User Testing.” https://www.nngroup.com/articles/stakeholders-and-user-testing/.

Appendix A

Stakeholder Interview Questions

Interviews could consist of some or all of the following questions. Some questions could be asked in an online survey prior to the in-person interview to shape additional questions.

- Please describe the areas of our web presence you interact with, and your essential duties, responsibilities, and interactions with them.

- Is there anything not on this list that should be? (provide a list of known services)

- What are the platforms you are using for this content/site?

- Are there any external services integrated into the platform? (plugins, widgets, etc.)

- Do you have any existing documentation about the areas of the web presence that you use?

- Do you have any inventories of the content that currently exists on this site/platform/service?

- Do you currently use any type of analytics to track the use of this site or platform?

- Who is the best person to contact about this site/platform/content?

- Is anyone else directly involved with this site/platform/content?

- Who is responsible for creating accounts and setting permissions?

- How often is this content updated? Do you have a schedule?

- Is access to this content/site/platform limited to a specific person or group?

- How is this content/site/platform accessed? (location, logins, etc.)

- How long should this content be available? (Is there an expiration date?)

- What is the status of this area of the web presence? (current, or legacy)

- How many pages (roughly) do you think you have?

- What are the types of content you are working with?

- Who is the primary audience you are trying to reach?

- What are your goals and objectives for this/these area/s of our web presence?

- What challenges are you currently facing with our web presence?

- Are you able to communicate effectively within this space, or are you using other workarounds?

- Is there anyone else we should talk to?

- Is there anything else you think we should know?

Appendix B

Appendix C

Voice and Tone Worksheet (PDF)

About The Authors

Tara M. Wood (wood19@uic.edu) is Web Services Librarian at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Cate Kompare (cmkompare@gmail.com) is a User Experience Designer and Researcher at Pixo.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply