By Shayna Pekala

Introduction

Discoverability is a crucial component of open access, yet it is one that is often overlooked. While web search engines serve as the primary vehicle for the discovery of open access content, much of that content, particularly within institutional repositories, is not fully optimized for display in Google search results. Search engine crawlers look for Schema.org vocabulary represented as structured data to understand and ultimately display web page content; however, this is not presently built into any widely-used institutional repository solutions.

Schema.org is a shared vocabulary created by search engines to make web content understandable to web crawlers and other machines. It is composed of 589 hierarchical types and 860 associated properties [1], which were created to be intentionally broad to facilitate mass adoption (Ronallo 2012). Schema.org is applied to a web page by embedding it into the HTML in one of three formats: microdata, JSON-LD, or RDFa. In an effort to enhance discovery of institutional repository materials in the open web, some academic libraries have incorporated Schema.org into their institutional repositories with varying degrees of complexity and customization.

Background

Over the last two years, Georgetown University Library has engaged in efforts to integrate Schema.org vocabularies with microdata in its institutional repository and digital collections portal, DigitalGeorgetown [2]. DigitalGeorgetown was launched in 2009 and is built on the DSpace repository platform. It’s managed by the Library’s Digital Services Unit in the Library Information Technology (LIT) department, and currently houses over 535,000 items. A significant portion of the records in DigitalGeorgetown are citation-only (69%), and of the remaining 165,925 records, 67% are open access, and 33% are restricted access.

In 2015, LIT began exploring ways to make the items in DigitalGeorgetown more discoverable in search engine search results and became interested in integrating Schema.org into the repository. The goal was to do this in the simplest way possible, using only the core Schema.org vocabulary (as opposed to creating any new types or properties). The microdata format was selected because, at the time, it was the format recommended by Google [3].

After testing the application of Schema.org in the form of microdata to a single community in DSpace, LIT decided to extend its use in the repository. In Fall 2016, Schema.org microdata was applied to all communities and collections in DigitalGeorgetown (with the exception of collections that exclusively had citation-only records and those that had a majority of restricted access items), and in spring 2017, a formal assessment was conducted to measure the impact of the implementation on Google search results. This paper documents the workflows used for applying Schema.org microdata to DigitalGeorgetown, the strategies used for measuring impact, and the results.

Literature Review

A handful of other academic libraries have also explored the use of Schema.org with their institutional repositories. Hilliker et al. (2013) at Columbia University describe how they added Schema.org markup using microdata to their Fedora- and Blacklight-based digital repository (Columbia University Academic Commons … [updated 2017]) as one of four approaches to making their repository interoperable. Developers mapped existing MODS metadata fields from the repository to corresponding properties in the Schema.org CreativeWork type (they eventually expanded to include other types) and updated the Blacklight code to insert the appropriate attributes into the HTML in the repository. They anecdotally observed that the microdata didn’t seem to provide any additional end user functionality, but no formal assessment was conducted.

Mixter et al. (2014) at Montana State University Library detail how they created their own Schema.org extension vocabulary for theses and dissertations in their institutional repository because they found the existing classes did not offer enough specificity. They used the new vocabulary to convert all of their 1909 theses and dissertations into RDF using OpenRefine, and published it as RDFa in their institutional repository. In the future, they planned to begin tracking the amount of structured data that is harvested by search engines.

Sexton and Aery (2013) at Duke University Library presented at the Coalition for Networked Information (CNI) Spring 2013 Membership Meeting on their approach to adding Schema.org to their digital collections portal using RDFa as part of larger project to use a customized Google Site Search interface for their digital collections. They used Schema.org properties to create their own rich snippets within their Google Site Search. They observed that since they began using Schema.org, most objects didn’t look any different in big Google searches, but did not detail how they tracked this.

Walli et al. (2017) at Europeana explain how they implemented Schema.org in their digital collections portal using JSON-LD. Their work focused largely on mapping the European Data Model (EDM) metadata from their digital collections to Schema.org. They also proposed strategies for gathering analytics to assess the effects of adding Schema.org to the sites but have not yet implemented them.

Implementation

Content Selection

In Fall 2016, Schema.org was applied to all DigitalGeorgetown communities and collections using microdata, excluding those containing primarily citation-only records and/or restricted access records. This decision was made in order to create the widest possible access to materials in the repository, while respecting the wishes of the collection managers of restricted access collections. In order to decide which Schema.org types to use, a content assessment of the repository was conducted. The content in the repository was reviewed to determine which types of items existed in the repository and which of those had corresponding Schema.org types. Based on this assessment, six Schema.org types were selected for use: VideoObject, Book, VisualArtwork, Photograph, ScholarlyArticle, and CreativeWork. Types were implemented at the highest level possible in DSpace (typically at the community or sub-community level, but occasionally at the collection level) based on the contents (Table 1). This enabled the Schema.org data to “trickle down” to the sub-communities and sub-collections, when applicable. Communities and collections made up of multiple item types were often mapped to the broader CreativeWork type.

|

DSpace Community/Collection Name |

Schema.org Type |

|---|---|

|

Woodstock Theological Library Collections, Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives Transcripts, University Archives, Manuscripts Collections, Law Library |

CreativeWork |

|

Institutional Repository |

ScholarlyArticle |

|

Georgetown University Publications, Rare Book Collections, Special Collections Catalog |

Book |

|

Art Collections |

VisualArtwork |

|

Initiative on Technology Enhanced Learning (ITEL) Digital Archive, Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives Videos |

VideoObject |

|

EnVision Church |

Photograph |

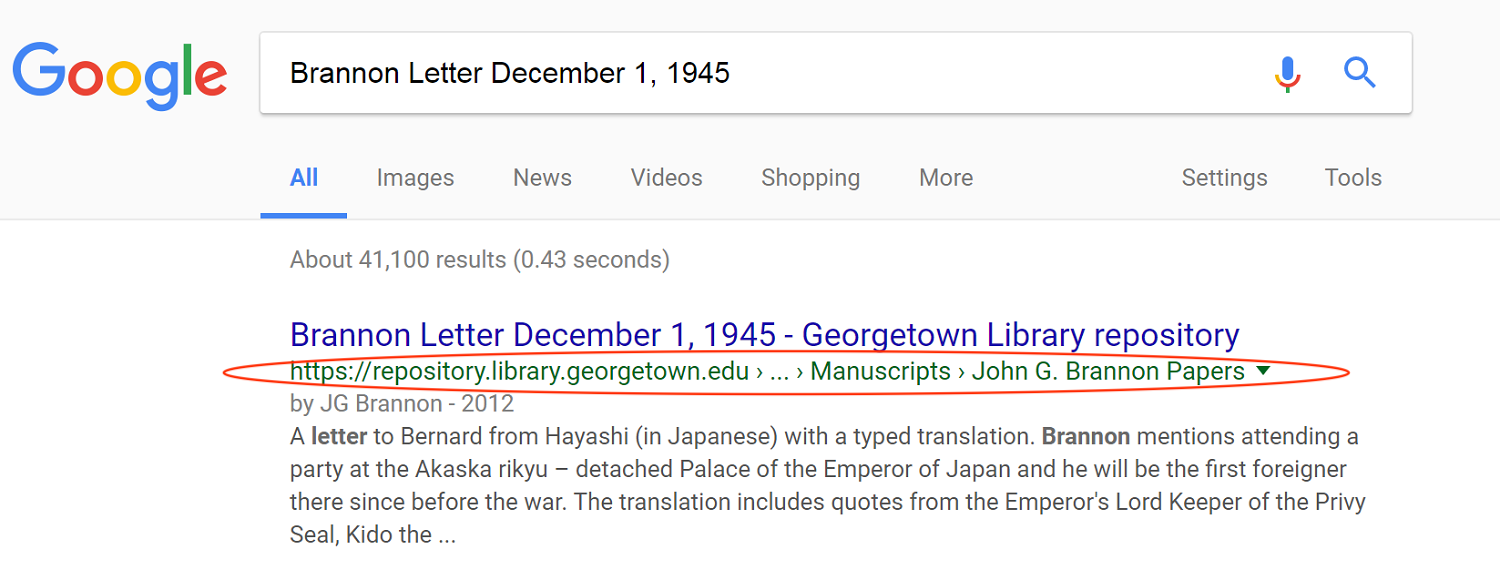

In addition to using types based on content, two types based on page structure were also selected: WebSite and Breadcrumb. LIT was especially interested in employing the Breadcrumb type because Google uses this type to display a breadcrumb trail in search results (Figure 1). The breadcrumb trail is what Google uses to indicate in the search results where a page falls in the website’s hierarchy (Breadcrumbs … [updated 2017]), and helps the user quickly understand the context of the search result in the larger website.

Figure 1. Breadcrumb Display in Google Search Results

Metadata Mapping

Because all of the selected types are sub-types of CreativeWork, many properties were inherited and therefore shared among types. LIT was able to map the Dublin Core metadata used in DSpace to using many of the same properties (Table 2). A handful of Dublin Core fields mapped to properties only used for certain types (Table 3). One property associated with the VideoObject type, thumbnailUrl, was added even though it is not used in DigitalGeorgetown’s Dublin Core metadata because it is required by Google.

|

Dublin Core Field(s) |

Schema.org Property |

|---|---|

|

dc.creator, dc.contributor author |

author |

|

dc.contributor.other |

contributor |

|

dc.publisher |

publisher |

|

dc.title |

name |

|

dc.identifier |

url |

|

dc.subject |

about |

|

dc.description, dc.description.abstract |

description |

|

dc.relation.isPartOf, dc.relation.ispartofseries |

isPartOf |

|

dc.coverage.spatial |

contentLocation |

|

dc.description.version |

version |

|

dc.language |

inLanguage |

|

dc.date.created |

dateCreated |

|

dc.date.issued |

datePublished |

|

Dublin Core Field |

Schema.org Property |

Schema.org Type |

|---|---|---|

|

dc.date.accessioned |

uploadDate |

VideoObject |

|

dc.format.extent |

duration |

VideoObject |

|

(none) |

thumbnailURL |

VideoObject |

|

dc.identifier.isbn |

isbn |

Book |

|

dc.format.medium |

artMedium |

VisualArtwork |

|

dc.type |

artForm |

VisualArtwork |

Code Updates and Re-indexing

Once the metadata mapping was complete, one of LIT’s developers updated the DSpace code to automatically generate the Schema.org microdata and insert it into the HTML of both simple and full item record pages. This process took less than a week, and the code is available on GitHub at https://github.com/Georgetown-University-Libraries/DSpaceSolutions#microtagging-code. Following the release of the new code, an updated sitemap was submitted to Google to request re-indexing.

Testing and Viewing Results

To test the content-based microdata in the repository, the easiest method was to use Google’s Structured Data Testing Tool [4]. When a user enters a URL into the tool, Google displays the microdata it detects on the page along with any known errors. For instance, if a required property is missing, the tool flags where the expected property should be. LIT discovered that the tool shows an error for a property that is missing even if it is only required for the display of rich cards. Rich cards are information boxes with images that appear in a carousel at the top of search results for certain item types, but only when certain properties are present. Since the content in DigitalGeorgetown doesn’t have all of the required metadata for rich cards, LIT did not want or try to enable this feature; therefore, the errors shown in the Structured Data Testing Tool were irrelevant. It’s important to examine the errors from the Structured Data Testing Tool thoroughly and recognize that not all errors require action.

Google also shows the microdata it detects in the Structured Data Report [5] in the Google Search Console [6]. However, this report only displays microdata detected within the last month, and LIT observed that the data it displayed was unreliable. Another way to view the microdata is through changes that may be visible in the search results themselves (for example, the text from the “about” property may appear as the summary text in the search results), but this is not guaranteed. Google explains:

Using structured data enables a feature to be present, but does not guarantee that it will be present. The Google algorithm tailors search results to create what it thinks is the best search experience for a user, depending on many variables, including search history, location, and device type. In some cases it may determine that one feature is more appropriate than another, or even that a plain blue link is best (Introduction to structured data … [updated 2017]).

Assessment

Measuring the impact of adding Schema.org to DigitalGeorgetown with microdata proved more challenging than expected. While the presence of microdata on a webpage can be verified by using the Structured Data Testing Tool, there is no single way to measure its effect on search results. This is largely due to the fact that Google search result rankings are dependant on over 200 factors and are constantly in flux. According to Google, “When a user enters a query, our machines search the index for matching pages and return the results we believe are the most relevant to the user.” (How Google Search works … 2017). The search results a user sees are personalized based on search history, location, device type, and what Google knows about the user’s preferences (Introduction to structured data … [updated 2017]). Additionally, an item’s search result ranking may shift depending on how other websites around it change, and items with generic titles that encompass broad subject matter (i.e. “Parrot”) have to compete with many more websites and may not show up in the first few pages of results.

Keeping these caveats in mind, LIT developed three questions about the impact of microdata in DigitalGeorgetown and identified a metric for each. These questions were:

- Did items rank higher [7] in Google search results after implementation than they did before?

- Did items display a breadcrumb trail in search results after implementation?

- Did referrals from Google to DigitalGeorgetown increase after implementation?

Search Results Rankings

To determine if items ranked higher in Google after implementation, LIT sampled thirty randomly selected items from representative collections and Schema.org types and measured the ranking of each before and six months after implementation. Two searches were conducted for each item, the first using the item’s title for the search terms and the second using the author’s last name and a partial title for the search terms. All searches were conducted in Google Chrome browser (logged out of any Google accounts) in Incognito Mode. If the item was not found in the first five pages of results, it was not counted. LIT conducted a separate sampling for images and videos in Google Image Search using ten randomly selected items of the Photograph and VisualArtwork types and in Google Video Search using five randomly selected items of the VideoObject type.

For Google Web Search, 26.67% of search results rankings increased, 18.33% decreased, and 55% showed no change. For Google Image Search, 10% of search results rankings increased, 30% decreased, and 60% showed no change. For Google Video Search, none of the items showed up within the first five pages of results both before and after the implementation.

Breadcrumb Trail

To determine if a breadcrumb trail displayed in the search results after implementation, LIT used the same items and search strategies from the search results ranking assessment and observed whether a breadcrumb trail appeared in search results six months after implementation. LIT found that 39.39% of items that showed up in search results had a breadcrumb trail displaying.

Google Referrals

To determine if Google referrals to DigitalGeorgetown increased after implementation, we used Google Analytics to compare the total number of Google referrals to DigitalGeorgetown from the six months following the implementation (August 2016-February 2016) with the number of referrals from the same six month period over last three fiscal years. We found that there was substantially higher growth rate in 2016 (63.30%), compared to average growth rate from the last three fiscal years (23.27%).

Discussion

Examining three different metrics helped to provide a fuller picture of the microdata’s impact on Google search results. While the search results ranking data demonstrated an overall positive impact for Google Web Search, over 50% of results still showed no change in ranking. Interestingly, the search results ranking data for Google Image Search demonstrated an overall negative change, which is likely due to factors outside of LIT’s control. Additionally, the search results ranking data for Google Video Search showed that the microdata had no impact at all, as none of the items showed up in results before or after the implementation. Google Video Search requires items to have a “thumbnailURL” property in order to be included in results, yet none of the videos in DigitalGeorgetown have thumbnail images, so that property was left blank. In addition, the videos don’t actually live in DigitalGeorgetown, but are embedded from ShareStream. The combination of these factors could have easily led to the videos absence in Google Video Search results.

The relatively low number of breadcrumb trails appearing in search results (39.39%) was disappointing, but not surprising. As mentioned earlier, Google emphasizes that just because a feature (such as breadcrumbs) is enabled, this does not guarantee that it will be present in search results (Introduction to structured data … [updated 2017]). The significant increase in Google Referrals was the most encouraging metric. Presumably, the reason for this growth is that items are now more visible in Google search results, so they are clicked on more frequently, resulting in a higher referral rate.

Overall, the results of our assessment show a small, yet visible impact on search results. While the presentation of results in Google search was inconsistent across items, there were certain observable changes, including fluctuation in search result ranking, appearance of a breadcrumb trail, and increased Google referrals. Libraries taking on a similar project should be aware that Google may take a long time to recognize the presence of microdata in a large repository like DigitalGeorgetown, so it is important to set expectations accordingly and to ensure enough time passes before comparing the before and after of search results.

Conclusion

This project demonstrates a low-barrier approach to integrating Schema.org vocabularies into an institutional repository using microdata. One of the most time-consuming parts of the process was selecting which types and properties to use because there are so many options within Schema.org and because they will necessarily be unique to each institutional repository depending on which metadata fields are already in use. Demonstrating impact was also difficult because there are so many factors that influence how search results display in Google and are beyond the library’s control. Additionally, changes in search results aren’t immediately visible or consistent; therefore, assessing multiple metrics to paint a larger picture of the overall impact is key. While the use case described in this paper is specific to DSpace, similar workflows and assessment strategies could be applied to any open source repository. Overall, the work completed had small, but positive effects on the visibility of DigitalGeorgetown items in search engine results, helping to improve the discoverability of the Library’s open access resources.

Notes

[1] http://schema.org/docs/schemas.html

[2] http://www.library.georgetown.edu/digitalgeorgetown

[3] Google now recommends using JSON-LD according to https://developers.google.com/search/docs/guides/intro-structured-data.

[4] https://search.google.com/structured-data/testing-tool

[5] https://www.google.com/webmasters/tools/structured-data

[6] https://www.google.com/webmasters/tools

[7] “Higher” meaning that the result appears closer to the top of the page, as opposed to the number of the result. For example, a search result ranking of three is higher than a search result ranking of ten.

References

Ronallo, J. 2012. HTML5 microdata and Schema.org. Code4Lib [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 31]; 16. Available from: http://journal.code4lib.org/articles/6400

Columbia University Academic Commons [Internet]. [updated 2017 Jul 28]. Nottingham (UK): University of Nottingham; [cited 2017 Jul 31]. Available from: http://opendoar.org/id/1317/

Hilliker, R., Wacker, M., Nurnberger, A.L. 2013. Improving discovery of and access to digital repository contents using semantic web standards: Columbia University’s Academic Commons. Journal of Library Metadata [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 31]; 13(2-3): 80-94. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19386389.2013.826036

Mixter, J., O’Brien, P., Arlitsch, K. 2014. Describing theses and dissertations using Schema.org. In: Moen, W., Rushing, A., editors. Metadata intersections: bridging the archipelago of cultural memory. Proceedings of the international conference on Dublin Core and metadata applications; 2014 Oct 8-11; Austin. Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. p. 138-146. Available from: http://dcpapers.dublincore.org/pubs/article/view/3715

Sexton, W., Aery, S. 2013. Video: Using Schema.org & Google Site Search with with library digital collections [Internet]. Washington, DC: CNI; [cited 2017 Jul 31]. Available from: https://www.cni.org/news/video-using-schema-org-google-site-search-with-library-digital-collections

Walli, R., Isaac, A., Charles, V., Manguinhas, H. 2017. Recommendations for the application of Schema.org to aggregated cultural heritage metadata to increase relevance and visibility to search engines: the case of Europeana. Code4Lib [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jul 31]; 36. Available from: http://journal.code4lib.org/articles/12330

Breadcrumbs [Internet]. [updated 2017 Jan 26]; Mountain View, CA: Google; [cited 2017 Jul 31]. Available from: https://developers.google.com/search/docs/data-types/breadcrumbs

Introduction to structured data [Internet]. [updated 2017 Jul 10]. Mountain View, CA: Google; [cited 2017 Jul 31]. Available from: https://developers.google.com/search/docs/guides/intro-structured-data

How Google Search works [Internet]. 2017. Mountain View, CA: Google; [cited 2017 Jul 31]. Available from: https://support.google.com/webmasters/answer/70897?hl=en

About the Author

Shayna Pekala (shayna.pekala@georgetown.edu) is the Discovery Services Librarian at Georgetown University Library, where she administers and supports the library’s discovery systems, including the integrated library system, catalog, and discovery layer. Her research interests include discovery tools, user experience, and privacy.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply