by Jonathan E. Germann

Introduction and background

The library role of gatekeeper and gateway to information has been expanding in a networked environment. Valuable digital information inside and outside paid database subscriptions has been expanding as well. Many information needs require raw or custom datasets for direct manipulation. For example, library patrons will often find themselves in need of compiled source data from a website in a spreadsheet like program to analyze. Patrons may need to combine data from various sources or track source information over time. Unfortunately, much, if not most, of this information is not created or optimized for digital manipulation but for direct human consumption.

A staggering amount of information is available online to meet these needs. For example, Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Facebook are estimated to hold 1,200 petabytes of data alone. Open access Common Crawl is downloading and indexing approximately three billion open web pages quarterly for future public consumption and manipulation. As of October 2017, it is estimated that 47 billion web pages exist on the Internet. Of these 47 billion, it is estimated that only five billion are indexed.

Most web pages are designed and optimized for direct human interaction — information marked with HTML to be interpreted and visually displayed in a web browser. When examining network traffic, however, most activity on the Internet is attributed to automated spiders/bots. These bots are downloading, indexing, and recompiling information embedded in web pages to create new tools, meaning, and insight. Regrettably, only those who understand the complexities of retrieving and extracting networked information can gain additional insight from these billions of information sources.

Libraries have historically filled unmet information gaps. There is a need for datafied information and custom datasets. Access can only be created with bots to pull custom information out of web pages. Libraries can fill this current growing information gap by focusing on the data residing in the billions of Internet pages.

Internet data has a high volume, variety, and velocity. This information is beyond library curation abilities — there are too many websites to curate and too many diverse information needs. Libraries can instead focus on curating tools to wrangle data for patron use. Specifically, focus on library sponsored services and educational outreach assisting users in locating and extracting relevant information. Librarians must get proximate to the millions of websites holding valuable information by assisting in the creation of custom bots and tools.

Browsing the modern web

Web pages are transferred via Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP: which mainly utilizes GET, POST, PUT, and DELETE requests) to be rendered for human consumption by a browser. The process is fairly straightforward: content is requested via HTTP, the response is interpreted and rendered by a browser (HTML, XML, CSS, XPATH), and content is manipulated dynamically using JavaScript and the DOM API.

The process of rendering a web page over HTTP is simplified into four steps, beginning when a URL is typed into a browser. When a user types an URL into a browser/clicks a link, a number of actions take place. First, the domain name, or the initial part of the URL, is used to lookup the appropriate web server. Second, the remaining end of the URL, in conjunction with other information like cookies and browser version, is sent as a request to the server by the browser. Third, the server replies (hopefully!) by sending an HTML file. Fourth, the HTML is interpreted by the browser and translated into a Document Object Model (DOM, a tree representation of the page). The DOM representation is rendered in the browser and users can interact with the information.

Modern web page rendering is largely driven by structured data (databases, XML, JSON) and scripts (JavaScript/AJAX/JQuery) formatted according to W3C standards. Web pages are designed to be delivered to browsers that parse the HTML/CSS into standardized structures (the Document Object Model). These structures enable dynamic content creation and monitoring through the DOM API. The DOM API can be accessed by scripts (JavaScript/JQuery/AJAX) to dynamically change content in real time.

The complexities of this process are normally handled by the web browser with a human interacting with the information to drive further requests or dynamic page changes. These processes together form a well-structured web API — an API normally designed and optimized for a web browser and human team.

Manipulating the web API is fairly straightforward when needing to create custom datasets. The complexities arise when it is necessary to automate the human part of the team.

Web scraping in Python

There are a number generic web crawlers for obtaining bulk website data (Apache Nutch, Wget, cURL). However useful in crawling through entire websites, they lack functionality in obtaining targeted data. For targeted web scraping tasks, Python excels. Python is a user-friendly programing language that has a vibrant web scraping community.

The below inexhaustive list of Python packages will assist in obtaining targeted information from almost any web page on the Internet. They are used to request appropriate information and then parse the results.

- Urllib is a package for directly working with URLs. Modules facilitate requests for opening and reading URLs, error handling for parsing exceptions raised, and parsing for navigating URLs and robots.txt files. Urllib is good for the direct requesting of responses from a server (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE). It does, however, need to be used in conjunction with an HTML/XML parser to extract data. For more information, see: https://docs.python.org/3/library/urllib.html

- Selenium is a package that automates web browsers. Although originally designed for testing purposes, it is also currently valuable when attempting to navigate modern web pages that run on JavaScript. It excels at manipulating web pages through XPath (XML Path Language for querying web page information) and removing most programming complexities by utilizing the browser for complex user-agent checking, cookies, and add-ons. Selenium can be resource intensive when using headed (visible) browsers. For more information, see: http://www.seleniumhq.org/

- BeautifulSoup is a package to navigate, search, modify and extract information from web formatted documents. It converts incoming web documents to Unicode and parses pages into navigable trees for easy data manipulation and extraction. Named after a poem in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, BeautifulSoup attempts to make sense of web pages. For more information, see: https://www.crummy.com/software/BeautifulSoup/

- Scrapy is a fully open source application framework built in Python for extracting and navigating web pages. It has developed a robust and efficient framework that is useful in handling concurrent requests for large or ongoing projects. Scrapy has a learning curve and in most cases must be used in conjunction with other tools (BeautifulSoup, headless browsers). For more information, see: https://scrapy.org/

Moral, legal, and practical considerations

Before performing automated data harvesting on a remote web server, it is prudent to consider the possible moral and legal issues. A website’s robots.txt file will indicate which part(s) of the website the owner does not want bots to crawl and/or index. Subscribed databases and password protected websites are usually governed by user or license agreements restricting automation. Servers also have physical restrictions. Irresponsibly fast scraping can slow the server to a crawl or act like a denial-of-service (DoS) attack.

In all cases, it is a good idea to obtain the data without leaving a noticeable footprint. Servers have safeguards, set intentionally or by default, that will block IP addresses or ban registered users at certain thresholds. Scraping slowly or during low traffic periods will keep scripts running smoothly and website owners unaffected.

Case study: obtaining warrant data

A legal scholar had an information need in obtaining bulk warrant data to examine demographic disparities. The necessary raw information did not exist in either paid or free websites. The information did exist on government websites but needed high-volume, repetitive downloading and parsing before the information would be useful or meaningful.

Austin was one government website that had the desired data in an unusable single-serving format (located at https://www.ci.austin.tx.us/police/warrants/warrantsearch.cfm). The data was available by searching by full name (two characters needed in both first and last fields) or birthdate.

Figure 1. Name search form for warrant data

The process for obtaining this data was 1) examining the website’s HTTP requests/responses, 2) creating a plan to loop over every relevant web page (here date of births (DOBs) in a database), 3) using a python package to obtain raw web pages, and 4) parsing results to extract relevant content to a CSV file. This approach also allowed for reexamining the data for accuracy verification.

1. Initial website inspection

Initial website inspection was performed by accessing the developer tools in Google’s Chrome Web Browser. Chrome developer tools allowed for inspection of web page elements and network traffic. If simple HTTP requests were performed during search, the best way to acquire the data would be to insert query terms directly into the HTTP request string. If data was being dynamically generated behind the scenes through DOM API access, a simulated browser would need to be used to navigate the web page.

Figure 2. Captured HTTP headers

Here, test searches initially performed on Austin’s Warrant search page revealed a HTTP POST request being utilized to return results. Austin’s website also used Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) tokens as added security. CSRF tokens could be handled using Python’s Requests package, Scrapy, or a web browser driven by Selenium.

Since low computer overhead or fast scraping speeds were not needed, the most programmatically friendly approach to extraction was using Selenium to drive searches while taking care of the CSRF/header/cookie complexities. First collecting the raw HTML results driving a headless Chrome instance and then parsing the raw HTML for desired warrant data with BeautifulSoup.

2. Loading dates of birth to SQLite

To collect possible results, the first step was to populate a database with a range of possible birthdates (relevant DOB searching being about 50,000 requests versus name searching at about 457,000 requests). Python’s Datetime package was used to populate a SQLite database.

from datetime import timedelta, date #To fill database with dates

import sqlite3 #The database

def createdb():

"""Creates a SQLite table. Date field for 100+ years of dates. Success

field for indicating if the date was successfully scraped. Warrant field

for indicating if any warrant was found on that date. HTML field for

storing the raw HTML web page responses"""

conn = sqlite3.connect('Austin.db')

conn.execute('''CREATE TABLE Data

(Success TEXT,

Warrant TEXT,

HTML TEXT,

Date TEXT);''')

conn.close()

def daterange(start_date, end_date):

'''Creates and yields dates using Python’s Datetime package.'''

for n in range(int ((end_date - start_date).days)):

yield start_date + timedelta(n)

def loaddates():

'''Connects to SQLite and loads each date into the database by iterating

through the "daterange" function.'''

conn = sqlite3.connect('Austin.db')

conn.text_factory = str

start_date = date(1900, 01, 01)

end_date = date(2017, 12, 31)

for single_date in daterange(start_date, end_date):

getdate = single_date.strftime("%m/%d/%Y")

print getdate

conn.execute('''INSERT INTO Data(Date, Success)

VALUES (?, ?)''', (getdate, "N/A"));

conn.commit()

conn.close()

3. Driving Chrome to collect HTML responses

A browser needed to be initiated, driven by Selenium, each possible date of birth injected into the search box, and resulting HTML saved to the SQLite database.

Selenium was used to drive a Chrome browser with custom options. To save computer resources, no visible browser was rendered. To enable the clicking of the submit button without elements overlapping, Chrome was opened with a virtual window size of 1000 x 1000.

import sqlite3 #To drive each search by date of birth. from selenium import webdriver #Browser control with options/waits/exceptions. from selenium.webdriver.chrome.options import Options from selenium.webdriver.support.ui import WebDriverWait from selenium.webdriver.support import expected_conditions as EC from selenium.webdriver.common.by import By from selenium.common.exceptions import TimeoutException import time #For slowing down the scraping process.

while error < 20:

""" Browser setup. Wrapping scraping loop in a condition: if the server

temporarily goes down or we run into errors -- we want to pause the scrape.

"""

chrome_options = Options()

chrome_options.add_argument("--headless")

chrome_options.add_argument("--disable-gpu")

chrome_options.add_argument("--window-size=1000,1000")

"""Opening Chrome in headless mode (does not render a visible browser),

with no GPU usage, with an imaginary window size of 1000 x 1000 (so we

can click on web links/buttons without them overlapping)."""

browser = (webdriver.Chrome(chrome_options=chrome_options, executable_path=

r'C:\Python27\selenium\chromedriver.exe'))

#Loops through HTML and calls "gethtml" function to extract table data.

drivebrowserbydb()

browser.quit()

print "Errors are " + str(error)

The Selenium webdriver can interact with a web page much like a human. Selenium can use the formatted document structure (HTML, CSS, XPATH) to locate and interact with page elements (by ID, Name, XPath, etc.). This information can be found by right-clicking and selecting inspect in Chrome. After examining these elements, each necessary ‘human’ step was added.

def gethtml(date):

""" A scraping function driven by looping over dates. This function takes a

date, performs a search on the Austin web page, and returns the raw HTML

response or error."""

global error

try:

"""Loads the Austin search page and waits up to 10 seconds for the warrant

date search form to appear."""

browser.get("http://www.ci.austin.tx.us/police/warrants/warrantsearch.cfm")

element = (WebDriverWait(browser, 10)

.until(EC.presence_of_element_located((By.ID, 'warrant_date'))))

"""Clears the date box, then inserts the search date into the box.

Waits for the submit button to appear before clicking it."""

element.clear()

element.send_keys(date)

element = (WebDriverWait(browser, 10)

.until(EC.presence_of_element_located((By.NAME, 'submit'))))

element.click()

"""Waits for the container box to load, waits for a prescribed time

(to slowly and politely request information from the server) and

returns the raw HTML to be stored in the SQLite database."""

element = (WebDriverWait(browser, 10)

.until(EC.presence_of_element_located((By.ID, 'container'))))

time.sleep(waittime)

html_source = browser.page_source.encode("utf-8")

return html_source

#If any of the above fails, an error is written to the SQLite database.

except Exception as e:

print e.__doc__

print e.message

error = error + 1

return False

4. Parsing the raw HTML to obtain needed warrant data

After ~50,000 DOB searches and corresponding HTML requests were obtained, the next step was to extract the warrant data into a spreadsheet for further analysis. The BeautifulSoup package was used for parsing HTML into a navigable tree (the tree can be navigated/selected by tag name or by parent/child relationships). The below is an example snippet of a BeautifulSoup tree for the Austin warrant data results.

<tbody>

<tr class="odd" role="row" valign="top">

<td class="sorting_1">

MOON

</td>

<td>

MOON, JANE

</td>

<td>

</td>

<td>

04/27/81

</td>

<td>

B

</td>

<td>

M

</td>

<td>

Bond: $ 125.00

The BeautifulSoup object had a clear table with two classes: odd and even rows. Therefore, the code to parse the object merely needed to pull information out of these two class labels. First, a BeautifulSoup object was created and searched for the table containing the warrant data. Then each cell containing data was parsed and formatted.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup #To create navigatable object.

import re #To remove whitespaces.

import sqlite3 #To pass previously scraped HTML to Beautifulsoup.

def getthings(rawhtml):

"""Raw HTML is being passed to this function. The function will pull

any available warrant rows and write them to an opened CSV file."""

try:

#Creates a BeautifulSoup object from raw HTML using a HTML parser.

soup = BeautifulSoup(rawhtml, 'html.parser')

#Used to print the BeautifulSoup tree structure for analysis.

print soup.prettify().encode('UTF-8')

#Creates a BeautifulSoup object containing both odd/even rows.

warrant = soup.findAll("tr", { "class" : ["odd", "even"] })

"""Loops over the object (over rows, then cells) to extract

warrant data. If no data exists, fills in BLANK. Writes to file

after each row."""

for row in warrant:

writerow = '~'

for cell in row:

try:

item = cell.text.replace(" ", "")

writerow = writerow + str(item) + "~"

except:

writerow = writerow + "BLANK" + "~"

output.write(str(writerow))

output.write('\n')

except Exception as e:

print e.__doc__

print e.message

return False

return True

5. Final output

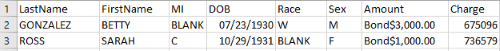

The data was written to CSV for end-user manipulation. Thousands of Austin warrants were parsed and saved to CSV to be manipulated and analyzed for demographic disparities.

Figure 3. Sample CSV formatted into table

Conclusion

Networked environments allow for advanced information exploration. The modern web runs on a handful of protocols and standards that together make an Internet API. Querying the API and compiling different datasets creates insight and meaning desired by patrons.

Libraries are uniquely positioned to facilitate access to the billions of web pages on the Internet. Librarians have access to subscribed databases/websites and have an in-depth understanding of the availability and reliability of resources on the open web. By learning simple Python and related packages, librarians can open these data sources.

For every patron their dataset. For every dataset its patron.

Bibliography

Common Crawl: Get Started[Internet]. [accessed 2017 Dec. 1] Available from http://commoncrawl.org/the-data/get-started/

Imperva Incapsula’s Bot Traffic Report [Internet]. [accessed 2017 Dec. 1] Available from https://www.incapsula.com/blog/bot-traffic-report-2016.html.

Kouzis-Loukas, D. 2016. Learning Scrapy. Packet Publishing.(COinS)

Mitchell, R. 2015. Web Scraping with Python: Collecting Data from the Modern Web. O’Reilly Media.(COinS)

Panchenko, Alexander et al. 2017. Building a Web-Scale Dependency-Parsed Corpus from CommonCrawl. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/1710.01779

Taddeo, M., Floridi, L. 2017. The Responsibilities of Online Service Providers. Springer. Retrieved from http://books.google.com

About the Author

Jonathan E. Germann (JD, MLIS) is the Digital Services Librarian at the Georgia State College of Law. JonathanGermannLaw@gmail.com

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply