by Andrew H. Bullen

Optical Music Recognition

I believe that music has a unique ability to give an almost visceral clarification of historical trends and events. As an (admittedly amateur) local historian, it has been frustrating to be presented with spectacular examples of sheet music that give shape and depth to history yet be totally inept at playing the tunes on a piano or other musical instrument. Happily, as it turns out, through a combination of Optical Music Recognition (OMR) and music composing software, I can scan the music, "read" it to detect the notes, time signature, etc., and tweak its playback to get just the right sound I want.

The process of turning sheet music into digitized files is neither straightforward nor error-free, but I believe well worth the effort. The skill set itself involved in a sheet music digitizing project is fairly basic: one needs to have some understanding of music theory, be able to read music, and be able to scan documents into an imaging software program such as Photoshop. However, the software that actually does the conversion, optical music recognition software, is relatively new and the software and recognition algorithms are less than ideal. Indeed, as stated in Gerd Castan’s page about OMR,

Doing OMR is hard. Very hard. If you follow the OMR science links, you will find much more theses about OMR than there are public[ly] available programs. [1]

As can be seen in the chart from Donald Byrd [2] , different OMR software packages vary widely in cost and technique. None of them comes close to achieving a success rate comparable to the best optical character recognition software.

Bringing Pullman Music to Life

My first attempt at using OMR software to bring music to life was with the Pullman State Historic Site's Pullman Virtual Museum [3]. The Pullman State Historic Site has a growing collection of sheet music related to Pullman travel and Pullman Porters. At the turn of the 20th century, Pullman– and particularly the phenomenon of the Pullman Porter– caught the public’s imagination. A journey on a Pullman car summoned up images of romance and adventure, and became a powerful symbol of new beginnings and accomplishment. An example of the Pullman car as metaphor for life’s journey can be seen in the 1873 farce-comedy Tourists in a Pullman Car written by William A. Mestayer and James Barton in which, as the train rambles along, the characters have adventures and romances [4]. The Pullman company was also one of the largest employers of African-Americans in the rigidly segregated society of 19th and early 20th century America [5]. Pullman Porters were generally the only African-Americans that much of white society ever casually interacted with [6]. As a result, Pullman Porters were also used in the era’s minstrel shows; many later minstrel productions cruelly featured the porter as a main character, portraying him as a cheerfully amoral ignoramus with a wife in every city [7].

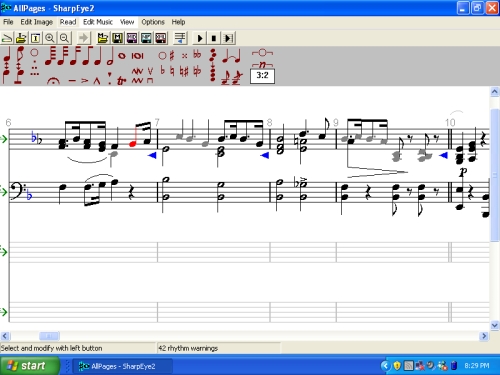

To give dimension to this aspect of lost America, we decided to digitize the sheet music in the collection in order to make it available through the Pullman Virtual Museum. The process began by first scanning each page of the sheet music into a TIFF file (no compression) at 400 DPI. I then tried to defox [8] and otherwise clean up the scanned image and clarify some of the staff lines and notes, extremal-boardwhich frequently bled and lost sharp definition during the scanning process. The next step was to use Visiv’s Sharpeye (http://www.visiv.co.uk/) music scanning software to actually batch the individual TIFF images together into one “tune” and OMR them. The Sharpeye OMR engine [9] is used by other OMR programs and can be counted on to give fairly good results. As I stated above, however, the error rate can be fairly high. As an example, the 1880 tune Tourists in a Pullman Car by George Bowron has 280 measures (5 pages with 14 measures of music, each consisting of 4 parts). Because of the condition of the paper, the conversion process resulted in 223 errors. Each error might consist of missing notes, improper time signatures, not enough/too many notes per measure, etc. All had to be corrected by hand, using Sharpeye’s editing features.

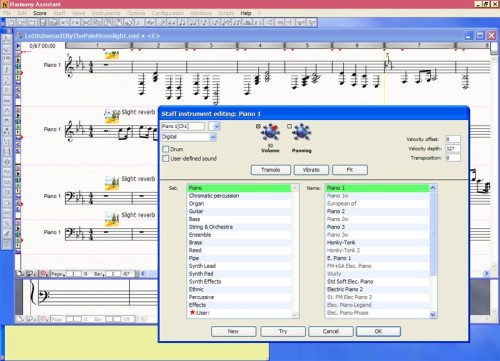

I wanted more control of the instrumentation and playback of the final product, so I used a second program, Myriad Software’s Harmony Assistant (http://www.myriad-online.com/en/products/harmony.htm). I like to use Harmony Assistant because of its powerful instrumentation and playback features. I was able to “tune” the output file of my Pullman tunes to sound like they were being played on the piano in the lobby of the Hotel Florence in the town of Pullman.

Image 1: The Hotel Florence, ca. 1885

Image 1: The Hotel Florence, ca. 1885  Image 2: The Hotel Florence’s lobby, 1892. Notice the Minton tile floors.

Image 2: The Hotel Florence’s lobby, 1892. Notice the Minton tile floors.A Case Study: Using OMR to Bring History to Life

OMR-ing sheet music is a very useful and worthwhile endeavor for librarians and museum staff alike, despite its time-consuming nature. It can provide a very powerful enhancement to an online exhibit, for example, or allow a library patron to download or purchase an aural “souvenir” of their visit, increasing library and museum visibility. Music is an ideal tool to connect users to information, because few phenomena evoke stronger emotional responses than music [11]. As an example of how a library might use OMR to bring an added dimension to a historical event, we can examine the process of digitizing sheet music using a tune that was indirectly responsible for a terrible tragedy. The music in question is the 1903 tune "In the Pale Moonlight," a part of the musical comedy Mr. Bluebeard.

On December 30, 1903, 1,900 Chicagoans flocked to the newly opened Iroquois Theater to see the latest Broadway hit, Mr. Bluebeard [12]. A lighthearted, big budget musical spectacular like Mr. Bluebeard was just what the city needed. December, 1903 in Chicago had been a very cold month and, with several bitter ongoing strikes, had also been a tense and acrimonious time despite the holiday season [13]. Holiday theatergoers packed the opulent theater for a Wednesday matinée. In the middle of the second act, the theater was bathed in pale blue light for the musical number “In the Pale Moonlight.” At about 3:15 p.m., a curtain brushed against one of the blue lights, setting the curtain immediately on fire. The fire spread rapidly out of control to the scenery flats above the stage. The almost non-existent firefighting equipment on hand was totally ineffective, and the supposedly impregnable fireproof curtain failed to lower completely. As actors and stagehands panicked and fled out the rear stage doors, the sudden gust of frigid December air from the opened doors created a huge fireball, filling the balconies with flame and superheated air. Escape for much of the audience was impossible. Many of the fire doors were locked, as the theater management wanted to prevent balcony patrons from sneaking down to the lower levels for better seats; in addition, what fire exits did exist were unmarked and hidden behind curtains with doors that opened inward. In a short time, 602 people had died, mostly women and children who had come to the afternoon matinée [14]. To this day, the Iroquois Theater fire remains the worst single-building fire disaster in U.S. history [15].

Among the 4 cast members who perished was the up and coming star aerialist Nellie Reed, playing a fairy, suspended on a trapeze 100 feet above the main floor when the fireball hit. She was to have gradually descended to the stage while sprinkling rose petals on the audience as she went by. In the ensuing panic, Ms. Reed was forgotten. Her trapeze was almost directly in the path of the fireball [16]. The last tune that she and 601 other men, women and children would ever hear sounded like this:

As a tribute to her, I have inserted a 2 beat pause towards the end of the music, right before the final dance number, where Ms. Reed was supposed to arrive on stage.

To produce the finished digital file is a multi-step process. The first step, of course, is to secure a copy of the music. Fortunately, there are several online collections of sheet music. The African-American Sheet Music Collection at Brown University (http://dl.lib.brown.edu/sheetmusic/afam/) as well as the Sheet Music Consortium’s wonderful OAI-PMH harvested collection at http://digital.library.ucla.edu/sheetmusic (harvesting the collections of Library of Congress, Duke University, Indiana University, UCLA, Johns Hopkins, the Maine Music Box, and the National Library of Australia) are great places to search. Many of the collections available at the Sheet Music Consortium’s site use PDFs; while there is OMR software that will read PDFs, I have found it better to download the PDFs files and save the pages as individual TIFFs. The next step is to defox the paper, cleaning up the staves, etc. in Photoshop. Be careful to save the TIFF file with no compression (Acrobat converts files to TIFFs with LZW compression when you do a “save as” to TIFF).

Image 3: Digitized sheet music.

Image 3: Digitized sheet music. Image 4: OMR processing results in Sharpeye, before any corrections.

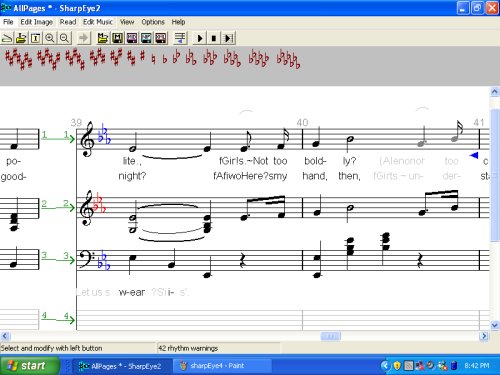

Image 4: OMR processing results in Sharpeye, before any corrections. Image 5: Correcting the key signatures.

Image 5: Correcting the key signatures. Image 6: Changing the instrumentation in Harmony Assistant.

Image 6: Changing the instrumentation in Harmony Assistant.Other OMR Software Programs

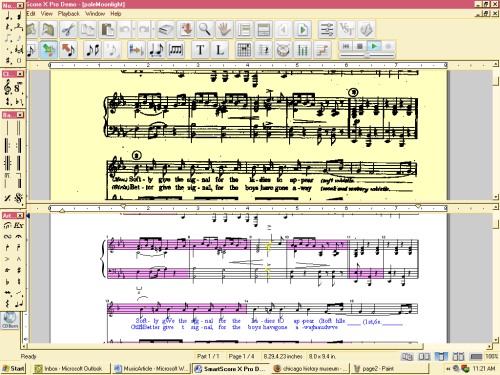

Of course, this is not the only way of using OMR. There are other OMR programs. A highly recommended program is SmartScore X Pro (http://www.musitek.com/smartscre.html). I did not purchase the software for this article (it runs to $399 USD), but the demo version seemed to have a superb recognition algorithm as can be seen below. Editing seems particularly easy.

Image 7: Initial pass through SmartScore X Pro

Image 7: Initial pass through SmartScore X Pro  Image 8: Initial pass through OMeR

Image 8: Initial pass through OMeR Notes

[1] See Music Notation’s OMP Web page at http://www.music-notation.info/en/compmus/omr.html.[2] See Donald Byrd’s OMR (Optical Music Recognition) Systems Web page at http://mypage.iu.edu/%7Edonbyrd/OMRSystemsTable.html.

[3] See the Sheet Music in Celebration of Pullman Web site at:

http://www.pullman-museum.org/exhibits/music/.

[4] Mentions of this farce-comedy can be found in the New York Times, News from the Theaters, Jan. 24, 1884, p. 3; New York Times, Theresa Vaughan is Dead, Oct. 5, 1903, p. 7; New York Times, Theatrical Notes, Jan. 4, 1880, p. 7. More information can be found about the farce-comedy theatrical genre and Tourists in a Pullman Car in specific in Smith, Cecil Michener. Musical comedy in America. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1950, p. 61.

[5] Sadly, the beginnings of legalized “separate but equal” segregation occurred because of the pivotal case of Plessy v. Ferguson in April, 1896, which was a dispute over whether Homer Plessy, 1/8 black, would be allowed to travel in a whites-only Pullman car through the state of Louisiana. For more information on Pullman porters and the Pullman company’s hiring practices of African-Americans, see Bates, Beth Tompkin. Pullman Porters and the Rise of Protest Politics in Black America, 1925-1945. Raleigh: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2001 (especially chapter 1). A good précis of Pullman Porters’ work experiences can be found at http://www.jmu.edu/writeon/documents/2006/McCray.pdf, McCray, Kim. Pullman Porters: The Best Job in the Community, the Worst Job on the Train. There are many, many works on the Pullman Porters’ experiences, listings of which are beyond the scope of this article, but a fascinating glimpse into a vanished America.

[6] Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. Bates, demographic stratification described throughout chapter 10.

[7] Kaser, Arthur LeRoy. Kaser’s complete minstrel guide: a collection of minstrel material for every occasion. Chicago: The Dramatic Pub. Co., [1934].

Inside the minstrel mask: readings in nineteenth-century blackface minstrelsy. Edited by Annemarie Bean, James V. Hatch, and Brooks McNamara. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan Univ. Press, 1996.

And, of course, a good example of a dramatic use of the Porter as a tragic buffoon can be found in the character of Brutus Jones in Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones.

[8] According to the Collectors’ Book Auction site (< a href=”http://www.collectorsbookmarket.com”>http://www.collectorsbookmarket.com/), foxing is defined as “The brown age spots thought to be caused by impurities in paper(e.g.: acid, exposure to humidity, etc.).”

[9] The Sharpeye OMR engine is called Liszt, and is thoroughly described at http://www.visiv.co.uk/tech-mro.htm.

[10] Photo from Koopman, H.R. Pullman: The City of Brick. Roseland (Chicago), IL: H.R. Koopman (privately published), 1893.

[11] Indeed, this is the whole basis behind the field of music therapy. This has long been a recognized phenomena; see, for example, Burton, Robert. The Anatomy of Melancholy. London: 1621. (Project Gutenberg edition at http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/10800).

[12] It is interesting to read the opening night review of the play in the New York Times, “Mr. Blue Beard” on Broadway, Jan. 22, 1903, p. 9.

[13] There are many works and web sites on the tragedy. See, for example, Brandt, Nat. Chicago Death Trap: The Iroquois Theatre Fire of 1903. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003.

[14] It is heart-rending to read the contemporary Chicago Tribune accounts of the tragedy. A newspaper column headlines from Dec. 31, 1903, p. 4, says it all: “BODIES REMOVED BY WAGONLOADS. Police vehicles and ambulances prove inadequate for the dead. Patrolmen forced to fight for passage through frenzied throngs.”

[15] The National Fire Prevention Association has a chart of these tragedies at http://www.nfpa.org/itemDetail.asp?categoryID=954&itemID=23343&URL=Research%20&%20Reports/Fire%20statistics/Deadliest/large-loss%20fires&cookie%5Ftest=1. The most recent large fire occurred in Rhode Island, at the Station, a nightclub, on Feb. 20, 2003. The loss of life in this fire, 100, ranks it at 17th place.

[16] Brandt, Chicago Death Trap, p. 85. Ms. Reed apparently made quite a living appearing in theatrical performances. I can find her first appearance in the New York Times, 4 new plays at the theatre this week, Nov. 3, 1901, p. 17.

[17] The Virtual Singer, in my very humble opinion, is approaching the spooky side of technology. Listen to how the Virtual Singer interprets La Vie en Rose: http://www.myriad-online.com/resources/demosvs/rose.mp3. Again, just my taste, but I have never used this particular add-on feature.

Author Information:

Andrew Bullen is the Information Technology Coordinator for the Illinois State Library, and a proud resident of the Pullman community. He can be reached at abullen at ameritech dot net.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply