By Matt Weaver

Introduction

As libraries consider the impact/future of ebooks in libraries, so much of that energy is spent on the actions of vendors and publishers. Digitization of local content holds a lot of potential for all libraries. Vendor-driven solutions are expensive and can be overkill for many types of information that libraries might want to digitize and distribute.

I came across some local cookbooks on my library’s shelves that represented a wide historical range, from a 2011 book produced by the city for Westlake’s centennial to one produced by a local church’s Sunday school in 1906, with several others in between. I wondered how we could capture that content, strip the recipes from their container, and create a database of local recipes. When looking for open-source digitization tools and processing tools, I realized that I could not only extract the recipes from the cookbooks, but also produce ebook copies. The result is The Community Cookbook, a recipe website and collection of ebook versions of local cookbooks.

The project is entirely open-source based:

- Homer project, suite of open source tools for the production of searchable PDFs when building projects from tiffs.

- Sigil, an open-source ePub editor

- Calibre, an open-source, multipurpose ebook program used for converting ePub ebooks into the Kindle-compatible mobi format

- Drupal, an open-source content management system.

A project like this shows that libraries of any size or budget can use open-source software for meaningful content creation. Because Westlake Porter Public Library hosts its own websites and owned all of the hardware used in digitization, The Community Cookbook project has been accomplished without any direct costs. What follows is an explanation of how WPPL developed this resource, and of the decision-making processes with regards to hardware, software, copyright and site infrastructure. Let’s begin with the hardware.

Hardware Used in This Project

Low-end PC

Bleeding edge technology is not required. The PCs that I have used for processing digitized images into ebooks were machines with average processor speeds at the time of their manufacture, running Windows XP.

Hard drives

The digitization process involves creating a large number of images. More images are created as part of the production process; the net result is large project files requiring adequate hard drive space. My current project file space for local ebooks exceeds 100 gigabytes for about a dozen ebooks. Ebook data should also be appropriately backed up on an external hard drive. When a pipe burst in my office this winter, releasing the contents of the library’s sprinkler system, I was fortunate that my hard drives survived.

Scanner

Flatbed scanners can be painfully slow, and are inappropriate for traditionally-bound books. Many cookbooks are published in spiral bindings so they can lay open when used in the kitchen. This binding makes them ideal for flatbed scanning. Around the time I started this project, the library acquired multifunction copier/printer/scanners that scanned books rapidly. On such a machine I could scan even a large cookbook in about twenty minutes. The scanners supported the tiff format.

DSLR camera

While there are different paths to ebook freedom, the method I use requires images to be in tiff format (more about formats later). A camera that shoots in tiff format is ideal, but RAW format, which is more common, can easily be converted to tiffs using the open-source image-editing program Gimp, or other common commercial products.

Digitization rig

A digitization rig is needed for scanning with a camera. Rigs can be elaborate and expensive, or downright elegant in their simplicity. Figure 1 is a rig that I cobbled together using a couple of bookstands that are held together with rubber bands. It got the job done.

Figure 1. Test rig used at WPPL.

Deciding on a Copyright Strategy

In creating local ebook collections, copyright is a primary consideration. When dealing with works covered by copyright, the Society of American Archivists posits the following principles [1]:

- Multiple legal rationales may apply to a specific project or use;

- Holdings in archival collections should be used, not left unused because of obscure ownership status;

- Common sense should apply.

Copyright issues

Under Section 108 of Copyright law, libraries cannot distribute electronically digital copies made for preservation. Section 104 of Copyright law prohibits the creation of an ebook version of a physical book that is still under copyright without the rightsholder’s permission. I could use neither Section 108 protections nor a Fair Use strategy for this project. To proceed with digitization, either the work would have to be in the public domain, or the library would have to get permission from the rights holder.

Few of these types of cookbooks were registered with the U.S. Copyright office, and hardly any feature a copyright statement, which factors into an item’s copyright status. Complicating matters is the fact that often I could not locate the rightsholder. Some organizations that had produced cookbooks no longer existed, and it was difficult to determine who would have held the rights.

Copyright and recipes

According to the U.S. Copyright Office [2], recipes can be subject to copyright: ingredient lists are not copyrightable, but instructions may be, if they amount to expression [3]. Anecdotes about a recipe, accompanying images, and any other original content in cookbooks may be copyrightable. Therefore, for the purposes of The Community Cookbook, in order to provide ebook copies of actual books, the only legitimate approach to copyright was to digitize titles that are public domain, and to seek permissions from the organizations that produced the cookbooks.

When considering this collection, I was unclear about how copyright would apply to these recipes. Even Cookbook Publishers Inc., a popular producer of fundraising cookbooks, states in its documentation that “individual recipes cannot be copyrighted” [4]. However, some of the titles that we have had access to were published by Cookbook Publishers and always carry a copyright notice. I emailed the company to ask if the copyright notice applied to the recipe content. A member of the company’s customer service department responded that copyright only applied to the artwork and other content provided by the company [5].

Therefore, if I received permission from the producing organization to digitize a cookbook published by Cookbook Publishers Inc., I needed to make sure that no artwork, or other publisher-provided content would end up in the ebook versions of the cookbooks. I created a template for book cover art that I use for cookbooks from Cookbook Publishers, Inc.

Researching copyright status

In order to research the copyright status of books that are potential candidates for digitization, I turned to several online resources:

- The Copyright office’s online catalog, which contains copyright records from 1978 to the present.

- Stanford University’s Copyright Renewal database, which contains renewal records for books published between 1923 and 1963. As renewals became automatic by statute starting in 1964, this database is a valuable resource for assessing the copyright status of works. Those renewals were received between 1950 and 1992.

- The Copyright Genie, from the ALA Office for Information Technology Policy and Michael Brewer, which guides a user in determining whether an item is in the public domain, through a series of questions about the work, and makes an evaluation of its copyright status. The user can generate a PDF with information about the work to document efforts to ascertain its copyright status.

- The Copyright Slider, also from Michael Brewer and the ALA Office for Information Technology Policy, is an easy-to-use interface for quickly determining a work’s copyright status based on its publication date, whether it contains a copyright notice, and some other factors.

Documenting research

It is important to document all copyright research, and that research be as detailed as possible. If someone claims to be a rightsholder of a work that you have digitized, providing documentation about the process by which you decided to use the work can help prove the legality of your actions or at least show that you employed thoughtful, professional methods in your evaluation of the content contained in your project. According to the Society of American Archivists, “A documented history of the search for a copyright holder should help establish that a good-faith effort was made” [6].

Consent agreements

When I determined that a cookbook was still covered by copyright, I would seek out the current head of the organization and ask for permission to digitize it. Since none of the cookbooks that I have digitized that are still subject to copyright had a single author, I determined that permission from the current head of the organization that produced the cookbook would be an appropriate indicator of permission. The consent agreement contains language that the signer of the agreement has the authority to approve our use of the cookbook.

For each work published after 1923 that I determined to be in the public domain, I thoroughly documented the research process in an Excel file in case I might have to justify my use of the content, and to document a good faith effort in attempting to identify rights holders.

Because, through this project, the library acts as a publisher, there had to be special consideration of how to handle access to the ebook as a digital object. My process for determining how users could access the content respected the concerns of the organizations that created the cookbooks without applying technologies that would both make the project cost-prohibitive and inject technological obstacles to patron access.

Access Control

There are two components to Digital Rights Management (DRM) that need to be considered in a project like this. Technological protection measures (TPM) represent the end-user technological obstacles commonly referred to as DRM. There is a second component to DRM, however: copyright management information (CMI) [7].

There are no TPMs used in The Community Cookbook ebooks. The content in this system is in most cases out of print, so it wouldn’t make any sense. This is clearly spelled out in the content agreement that is signed by representatives of organizations that produced cookbooks that are included in the collection.

CMI, however, is an important part of the digitization process. Data that comprises this category must be included in the digitization process, or it represents a violation of Section 1202 of US Copyright Law [7] [8]. CMI for cookbooks is preserved both in the ebooks and in fields for both recipe and ebook content types in the Community Cookbook website.

At this stage in the project’s development, only cardholders can access the full site. One collection, A Text Book of Domestic Science, a common Home Economics textbook from the early 1900s, which is in the public domain, is provided to all users largely as an example of how the site works. In the future, we may consider moving more titles beyond user authentication, but this will largely be determined by relationships with contributors.

Ebook Formats

ePub has been established as a standard ebook format by the International Digital Publishing Forum. There are two versions of ePub. Most ebooks are currently ePub2 format; but the ePub3 format, the current version of the standard [9], is gaining in popularity. The most significant difference between versions is that ePub3 does not use the Navigation Center eXtended (NCX) file. This file, which is used for navigation within the ebook [10], can be left in an ePub ebook file system so older ereading devices can still access the book. EPub3 also offers improved support for MathML [11].

Mobi is a Kindle-compatible format. While most ebooks for Amazon’s Kindle device are in Amazon’s proprietary AZW3 format (which is mobi-based), mobi offers the broadest Kindle device and app support. [12].

The ubiquitous PDF (Portable Document Format) is a terrible ebook format for ereaders, smart phones and small tablets. Designed to capture the exact layout of printed documents, the lack of adjustable text forces users of small tablets, smart phones and ereaders to pan and zoom in order to read a document. For users reading on a computer or large tablet, the PDF can provide an acceptable reading experience.

The Community Cookbook

Workflow

The content from the digitized cookbooks is stored on the Community Cookbook website in two ways: a recipe database; and a collection of ebooks in ePub, mobi and PDF formats. At the core of the recipe database is the Drupal recipe module, which provides functionality comparable to commercial recipe websites. Users can browse recipes by ingredient or recipe name; and download recipes in three formats that can be uploaded into recipe management tools and websites: mastercook4, recipeml, and plain text.

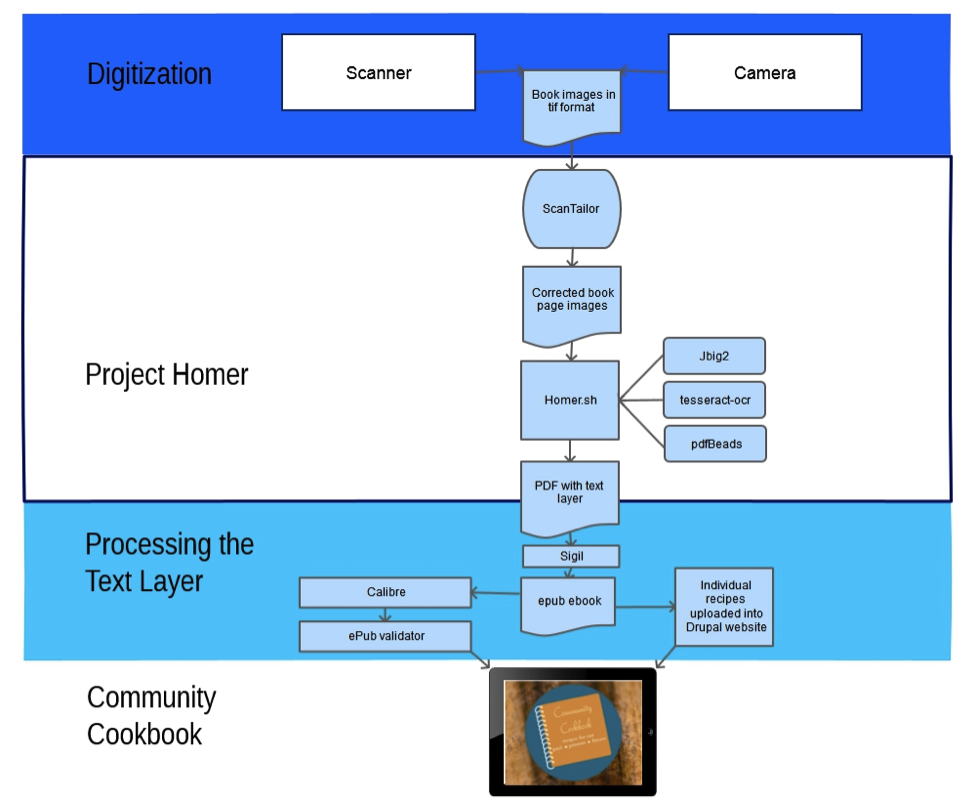

Figure 3. Digitization workflow.

There are three main stages in the workflow for The Community Cookbook project (figure 3). Stage one is digitization, using either a camera or flatbed scanner.

Optical character recognition is performed in stage two, beginning with tiff-format images from the digitization process and ending with production of a searchable PDF.

Stage three uses the text layer from the PDF, often after substantial editing, as the source of recipes which are uploaded into the recipe database, and to produce an ePub ebook which is later converted to a mobi ebook.

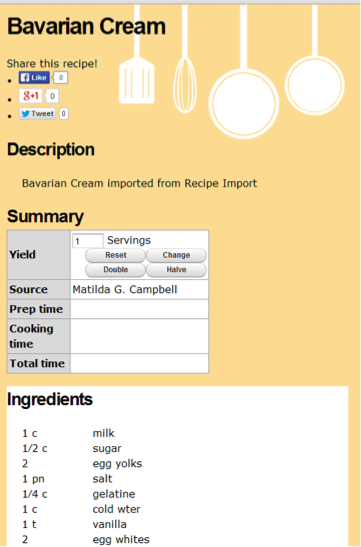

Figure 4. Sample recipe.

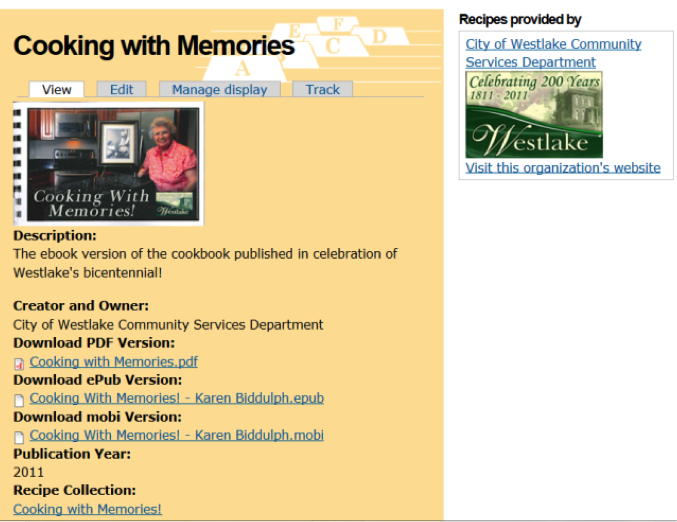

Key Drupal modules

Apart from ‘article’ and ‘page” content types that are part of Drupal out of the box, three others are at the core of the site’s functionality: recipes — produced by the Recipe module, ebooks, and organizations. The ebook content type has three file fields, one for each ebook format. The organization content type has fields for an organization’s logo, website address, and description. I felt it was important to give the organizations that produced the cookbooks a visual presence on the site. The organization information and logo appear alongside every recipe from their cookbooks (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Ebook connected to Organization content type.

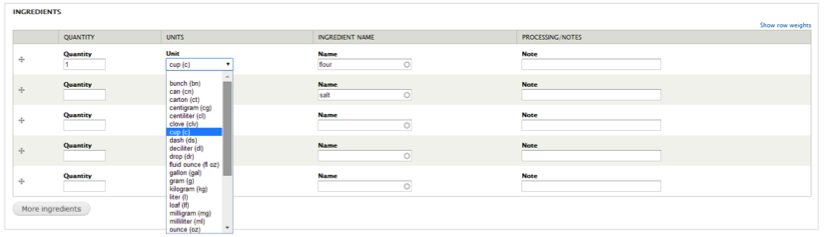

In terms of recipe metadata, the Recipe module [13] does a lot of the heavy lifting with its built-in management of ingredient and measurement data (figure 4).

Ingredients can be entered in a simple interface with dropdown selectors for measurements and autofill textfields for ingredients (figure 6).

Figure 6. Recipe ingredient interface.

One criticism of the module is that ingredients are not stored as a taxonomy, but rather as arrays in tables for the module, preventing their availability to the Views module.

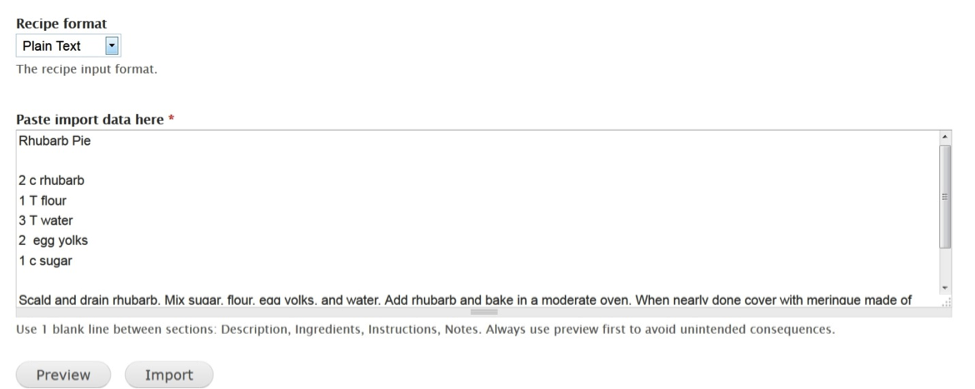

Recipes can be imported individually in either plain text, or mastercook4 format from a simple text box, allowing copying and pasting from other sources (Figure 7).

Figure 7. recipe import interface.

An essential module for maintaining the site is Views Bulk Operations (VBO) [14]. Through Views, VBO can be used to make changes to large numbers of content nodes in minutes. Because a cookbook can contain hundreds of recipes, I have set the default published status of all recipes to “unpublished”. When an entire cookbook has been entered into the site, I use VBO to publish all recipes for that cookbook en masse.

Content access

For the cookbooks and recipes that are restricted to library cardholders, the Taxonomy Access Control Lite (TACL) [15] module allows permissions to be set on content based on individual taxonomy terms. I created a “recipe collection” taxonomy, with terms — the titles of each cookbook — applied both to the ebook and recipe content types.

Out of the box, Drupal’s files are set as “public”. To control access to the ebook files, I changed the setting at “admin/configuration/media/file system” to “private files”. Unlike public files, which are accessed directly via the web server, private files are accessed via Drupal path requests [16], providing access control to those files, which the TACL module handles.

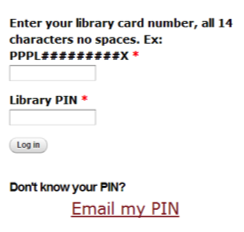

Because some of the organizations whose cookbooks I had arranged to digitize did not want their content shared with non-cardholders, I had to allow users to create accounts on the site, which Drupal handles out of the box. However, since the library already has a site that requires user accounts, I wanted to simplify account creation and site usage. The ILS authentication module [17] allows users to create an account simply by using a library card number and PIN. The module overrides the core user registration/login block (figure 8). There are costs associated with this, at least for libraries using SirsiDynix Symphony®. One has to subscribe to web services in order to be able to generate the client ID required to use the module. As my library had already subscribed to Sirsi web services, this module was easily added. Out of the box, Drupal provides user accounts. ILS authentication provides convenience for the end user.

Figure 8. ILS authentication module overrides Drupal user registration/login.

Usage

To capture usage data on recipes, I created a view that filters based on paths in the access log. All prints or downloads of recipes use a path that begins with “recipe/export”.

I use the Download Count module [18] to keep track of ebook download statistics. This module tracks downloads of private files, and gives the option of filtering out downloads by the site administrator.

Since late October 2013, the site has had more than 1,500 ebook downloads and more than 20,000 individual recipes have been downloaded or printed, content that cost the library literally nothing to acquire.

Future improvements

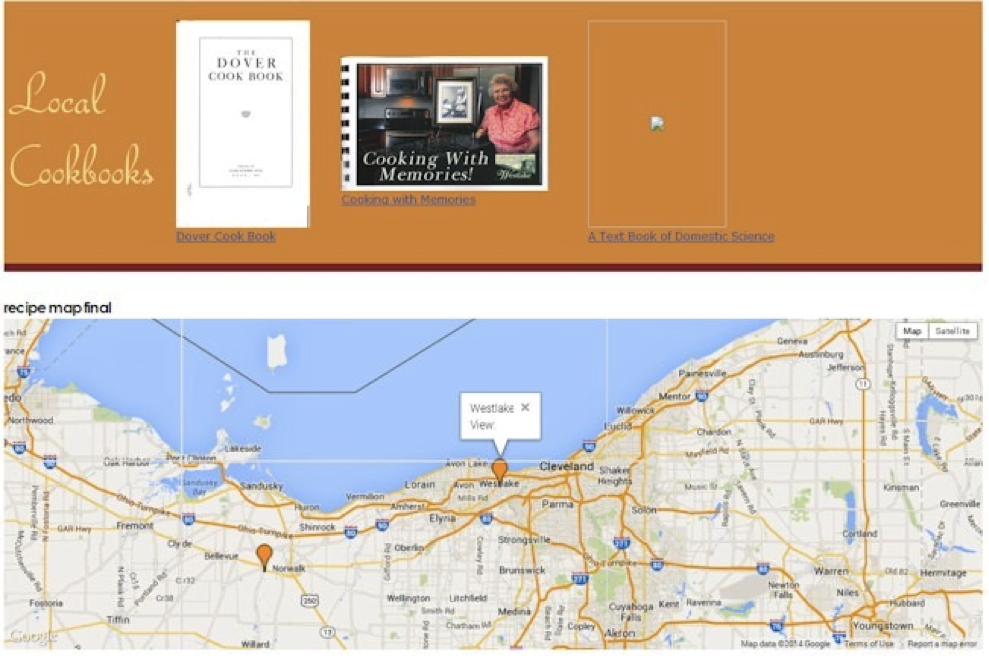

Mapping – I have received cookbooks that are outside the Westlake, Ohio, community, and are of regional interest. I have started looking at how to map cookbooks and recipes collections (figure 9). The website already uses location as a facet for recipe data, so adding a map is a natural interface

Figure 9. Testing mapping of collections.

Integration with local history content – Usually every recipe features the name of its source. I would like to combine recipes with images in our local history, and perhaps other sources to collocate as many historical items as possible. Adding recipes to images of people and families expands our understanding of their experience because we can see what people ate, beyond traditional historical information.

Developing a local publishing model – Based on the skills that I have developed and via the website that I have established, I would like to grow this project into a publishing service. As small organizations have a need to produce books for fundraising, the library could work with organizations to help produce ebook copies. In such a model, starting with content in electronic format eliminates the digitization and OCR parts of the workflow, reducing editing time. To help patrons produce books that can be printed, the open-source desktop publishing program Scribus [19] could be used. This program can produce PDFs, but also layouts that a printer would need to produce a physical book. The library would be able to help with content creation in every stage except printing. As organizations sell out of their print run, the library could attempt to negotiate the rights to those works.

The Value of the Experiment

Developing the skills to digitize, reshape and distribute content has the power to change our thinking with regard to electronic content, leading toward greater independence among libraries. By building projects/communities, we develop expertise in our communities that vendors cannot possess. Libraries of any type possess intimate knowledge of their communities.

The system developed in this project has low technological and cost barriers, and represents the first step in the development of an open source publishing model for libraries. A logical next step would be to provide publishing assistance for organizations, families, churches, etc., that want to publish cookbooks for fundraising purposes and facilitate design and layout.

Appendix

Open Source Tools Used

The Homer Project [20](lupocos, 2011) was begun as a way of developing low-cost, open digitization tools for museums, libraries, or anyone who wants to digitize books. It combines a number of free and open-source tools to make book digitization easy and affordable. Any of these components can be downloaded individually. If any of the following are already installed, they must be uninstalled before installing the homer software.

- ImageMagick (for manipulation images)

- Jpegtran (loseless jpeg transformation)

- JBIG2 encoder (compression tool for bi-level images)

- Tesseract-OCR – optical character recognition engine

- RubyInstaller (installs the Ruby programming language)

- Hpricot (HTML parser)

- RMagick (interface between the Ruby programming language and ImageMagick)

- PDFBeads (to create searchable PDF)

- Cmdow.exe (command-line utility used in Homer)

- ScanTailor (book page-processing tool)

- Homer.sh (bash script: command-line interface for producing a searchable PDF)

The Homer bash script can be used to rename and rotate the scanned images. Renaming can be an important step as, to a PC, page111.jpg will appear right after page11.jpg.

Many of these tools operate without any direct user interaction. The Homer bash script uses tesseract-ocr and PDFBeads to create a searchable PDF. The searchable text layer created by tesseract-ocr/PDFBeads is what allows the recipes to be stripped from the cookbook and uploaded individually into the Community Cookbook site. That text layer also can be copied into an ebook editor to create other ebook formats.

Some caveats

Installation: When launching the Windows installation executable, a number of open source tools are installed automatically. As part of the installation process, the usual installation displays will emerge and will proceed with the installation script taking complete control over the process. Each installation process for the components that Homer installs is controlled by the script, and progresses rapidly. Even if there is a pause, with a window that appears to prompt you for approval to proceed, no user action is needed.

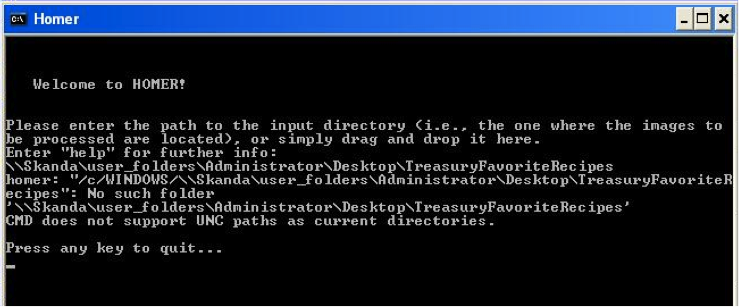

Figure 2. Homer warning.

Network profiles – Because the “CMD does not support UNC paths as current directories” (Figure 2) the Homer Project cannot be installed on a PC on a network’s domain controller, using a network profile. Homer cannot write the final PDF to the desktop.

cmdow – Antivirus software might quarantine cmdow as a hacking tool “because it can hide windows.” The cmdow project site recommends checking the checksum if you have any concerns about the file’s authenticity.

Troubleshooting the installation – I have installed homer on several PCs. Usually, all of the components are installed without a problem. If there are problems with the installation, the project can be uninstalled by running homer-uninstall.exe. Even then, some components might not have been removed. The above list of tools installed by homer can be used with the Windows software uninstaller in the control panel to see if any remain. Most of the components installed as part of homer require no human interaction. For instance, JBIG2 allows the creation of bi-level images so the text layer created by tesseract-ocr can be combined with the scanned image by PDFBeads to create the final searchable pdf. Below I discuss in greater detail the components that the user interacts with, and some other tools in addition to homer that are part of the workflow.

Tesseract-ocr [21] is a powerful optical character recognition engine that is installed as part of the Homer package. Packages have been developed for a large number of languages, from Afrikaans to Vietnamese.

ScanTailor [22], which is installed as part of the Homer package, processes scanned images of book pages. If images of book pages were scanned in double, they can be split. The software also deskews and despeckles text. ScanTailor supports right-to-left writing systems. The software produces an output directory (named “out”) that contains images, and an html file that contains the text. This output directory is dragged and dropped directly onto the Homer command-line interface. OCR is then applied via tesseract-ocr, and then PDFBeads produces the final searchable pdf.

Sigil [23] is an ePub editor that allows users with little or no XHTML experience to produce epub2-compatible ebooks. Sigil is not installed as part of Homer and must be downloaded separately.

Calibre [24] is the Swiss Army Knife for ebooks: one can use it to manage ebook collections, as a reader, and as a powerful tool to convert ebook books into a range of formats. For The Community Cookbook project, I have only used Calibre for dealing with books in ePub, PDF and mobi formats.

Kindlegen [25] is a program provided by Amazon for converting documents in various formats to mobi. This program is not open source, but it is free. There are restrictions on its use [26]. I haven’t used this tool as part of the Community Cookbook project; but having experienced some problems with mobi-format ebooks that had been converted with Calibre, I am looking into it.

EPub Validator [27] is a website powered by the open-source epubcheck system [28] to validate epub ebooks. The site is for non-commercial use only.

References

[1] Society of American Archivists (January 12, 2009). Orphan Works: Statement of Best Practices. Retrieved on May 5, 2014 from http://www.archivists.org/standards/OWBP-V4.pdf p. 2 (Back)

[2] U.S. Copyright Office. (Feb. 6, 2012). FL-122: Recipes. Retrieved on May 5, 2014 from http://www.copyright.gov/fls/fl122.html. (Back)

[3] Butler, Joy. (Jan. 29, 2008). Are Recipes Copyrightable? – Rights Clearance Observations about Julie & Julia, Deceptively Delicious, and The Sneaky Chef. Guide through the Legal Jungle. Accessed on May 11, 2014 from http://www.guidethroughthelegaljungleblog.com/2008/01/are-recipes-cop.html. (Back)

[4] Cookbook Publishers, Inc. Recipe Management. Retrieved on 4/22/2014 from http://www.cookbookpublishers.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/RecipeManagementTips3.pdf. (Back)

[5] Crosby, Debbie. (October 2, 2013). Email. (Back)

[6] Society of American Archivists (January 12, 2009). Orphan Works: Statement of Best Practices. Retrieved on May 5, 2014 from http://www.archivists.org/standards/OWBP-V4.pdf p. 11. (Back)

[7] Lipinski, Tomas. (May 8, 2014). Using Copyright and Licenses to Your Advantage in the Public Library Setting [workshop]. Ohio Library Council, Columbus Ohio. (Back)

[8] U.S. Copyright Office. (n.d.) Copyright Law of the United States of America, Chapter 12 section 1202. Retrieved on May 11, 2014 from http://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap12.html#1202. (Back)

[9] International Digital Publishing Forum (2012). Epub Validator. Accessed on May 5th, 2014 from http://validator.idpf.org/. (Back)

[10] Buse, Jarret W. (2014). EPUB from the Ground Up: A Hands-On Guide to EPUB 2 and EPUB 3. McGraw-Hill Education, New York, NY. p. 130 (Back)

[11] Buse, Jarret W. (2014). EPUB from the Ground Up: A Hands-On Guide to EPUB 2 and EPUB 3. McGraw-Hill Education, New York, NY. p. 170 (Back)

[12] Buse, Jarret W. (2014). EPUB from the Ground Up: A Hands-On Guide to EPUB 2 and EPUB 3. McGraw-Hill Education, New York, NY. p. 149, Table 6-3. (Back)

[13] tzoscott. (Sept. 28, 2003). Recipe module. Retrieved on May 5, 2014 from http://drupal.org/project/recipe. (Back)22

[14] https://www.drupal.org/project/views_bulk_operations. (Back)23

[15] Dave Cohen [sic]. (March 13, 2006). Taxonomy Access Control Lite module. Retrieved on May 5, 2014 from https://drupal.org/project/tac_lite. (Back)24

[16] arianek (2009, Dec. 1). Working with Files in Drupal 7. Drupal.org. Acquired on May 11, 2014 from https://drupal.org/documentation/modules/file. (Back)25

[17] jsherman. (January 26, 2012). ILS Authentication module. Retrieved on May 5th, 2014 from https://drupal.org/project/ilsauthen. (Back)26

[18] WordFallz. (Feb. 12, 2007). Download Count module. Retrieved on May 5, 2014 from https://drupal.org/project/download_count. (Back)27

[19] http://www.scribus.net/canvas/Scribus. (Back)28

[20] lupocos. (September 15, 2011). Home Page: Homer Book Scanner. Retrieved on May 5, 2014 from http://bookscanner.pbworks.com/w/page/40965440/FrontPage. (Back)13

[21] Tesseract-ocr. (n.d.). project page. Retrieved on May 4, 2014 from https://code.google.com/p/tesseract-ocr/. (Back)14

[22] Scantailor. (n.d.). Project page. Retrieved on May 5, 2014 from http://scantailor.org/. (Back)15

[23] https://code.google.com/p/sigil/. (Back)16

[24] Calibre. (n.d.) Project page. Retrieved on May 5, 2014 from http://calibre-ebook.com/. (Back)17

[25] Amazon.com. (n.d.) KindleGen. Retrieved on May 11, 2014 from http://www.amazon.com/gp/feature.html?docId=1000765211. (Back)18

[26] http://www.amazon.com/gp/feature.html?docId=1000599251. (Back)19

[27] http://validator.idpf.org/. (Back)20

[28] https://github.com/IDPF/epubcheck. (Back)21

About the Author

Matt Weaver is the IT Manager at Westlake Porter Public Library (Westlake, OH). His email address is mattrweaver1@gmail.com. You can connect with him at facebook.com/mattrweaver and twitter.com/mattrweaver, and see slides about this project at slideshare.net/mattrweaver.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply