by Christopher M. Jimenez and Barbara M. Sorondo

Introduction

Coinciding with the 20th anniversary of the publication of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s/Sorcerer’s Stone, we created a Happee Birthdae Harry display featuring a collection of resources on the boy wizard, magic, and recommended readalikes to promote our library’s resources at Florida International University (FIU). As a novel twist, we incorporated our @FIULibraries: Tap, Scan, Read project so the display contained both physical books and Near Field Communication (NFC)-enabled cards linking to ebooks and streaming media. These 6×8” cards were suspended above the physical books with string to produce a magical floating effect.

The @FIULibraries: Tap, Scan, Read project was conceived as an effort to leverage NFC technology to facilitate the discovery and use of digital resources, services, and wayfinding through posters, cards, and binders. As part of this first phase, we introduced NFC-enabled posters and cards to the students through the display in an engaging manner to familiarize them with the technology. With the wave of a “magic” NFC-equipped device, students could begin reading an ebook or watching a video in seconds! For those students chosen by a “wand” that lacks NFC support, both a Quick Response (QR) code and short URL were provided, no need to stop by Ollivanders or an electronics store for a new device.

The Happee Birthdae Harry Display was placed in a well-trafficked area by our library’s Circulation Desk, near an NFC-enabled poster promoting the library’s audiobook collection and a permanent “New Books” display. Within a month of the unveiling, it was evident the Harry Potter display was a spellbinding success. The physical books were checked out by the dozen while the e-books were accessed via the NFC-enabled cards nearly 100 times within the display’s first month. Moreover, within a month, use of the featured streaming videos exceeded the collective use of those videos for the previous five months. Furthermore, thanks to its proximity to the Harry Potter display, usage of the nearby NFC-enabled poster promoting audiobooks nearly doubled in the month since the display was introduced compared to the previous month.

Rationale

With Apple opening their NFC Controller to more application development over summer 2017, the iPhone/iPad ecosystem has now been brought into the scope of general NFC usage. Now these devices are no longer restricted to Apple Pay or other mobile payment solutions. This means that devices equipped with the ability to wirelessly transfer data will be in millions of current and future pockets.

The announcement was made in early June 2017 but the first downloads of iOS 11 were made public later that year, on September 19. Our Harry Potter display ran from June until the first few weeks of October, hence Android users were our predominant target audience during the display’s initial months, although we may have seen some iPhone NFC or native QR Camera interaction with our displays at the tail end of the display’s lifetime.

It is clear that the more people have access to and use NFC technology, the more demand we can expect to see for this type of functionality. Our results indicate there is interest among library users in consuming digital resources and interacting with library materials in innovative ways. In this paper, we describe our implementation of an NFC display that may serve as a practical, applicable example on how to use this technology in libraries.

Background

NFC is a short-range, wireless communication technology that establishes a temporary peer-to-peer network between two chips while they remain within four inches of one another as they complete a small data transfer. NFC tags, like the ones used in our displays, require no dedicated power source as they are activated by the smartphone or tablet that comes into contact with it. The required close proximity addresses security and privacy concerns as only a deliberate tap will initiate the transaction. The public may regularly use this technology without realizing it when they pay for goods using either their smartdevice or a credit card with an embedded chip.

While NFC is not a new concept, it is still sometimes viewed as a novelty. As early as 2012, anticipation and excitement for the budding potential carried by NFC technology was evident, such as Guevara’s (2012) belief that NFC had the potential to alter the way information is delivered. Early articles (e.g., Hoy 2013) described basic NFC operations soon afterwards, uniting several concrete applications under the banner of self-service operations (checkout, supplemental information, access control) that allow patrons to receive immediate assistance wherever they are and whenever they need it.

In a 2015 paper describing the first functioning and tested Android and NFC-based library transaction system, Yusof et al. (2015) reported high satisfaction with their application in user acceptance tests. They concluded the implementation of NFC technology has a number of technical advantages over other implementation methods such as QR codes, radio-frequency identification (RFID), and barcode scanning, which are often hampered by issues ranging from poor lighting impeding camera use to the use of proprietary applications and specialized equipment. Consequently, if NFC becomes an ubiquitous standard in smartphones, it carries tantalizing potential. It is this potential that has driven recent researchers (e.g., Abram 2017) to embrace NFC technology and claim this technology provides the newfound ability to transfer library resources conveniently into every pocket from physical locations.

Recently, Apple announced their intentions to open access to the NFC Controller on their developer’s platform during their Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC) in June 2017 (Introducing Core NFC… [updated 2017]). This means that developers can create applications which will make use of the NFC chip on the iPhone. For the first time, iPhone users will be exposed to the NFC apps that have existed for Android users since the early 2010s. This announcement has the potential to exponentially increase engagement, acceptance, and use of NFC technology.

The Project

Our project began as a student-funded technology proposal, approved in 2016 to enable librarians to marry digital objects to physical manifestations in order to allow students and other library patrons to quickly access digital objects and information with little hassle. The original proposal left plenty of space for innovation, and the project is now conceived as a multifaceted implementation that includes smart posters, e-resource cards, and a course reserves binder. The Harry Potter display is part of the second phase of this project, which is outlined in more detail on our @FIULibraries: Tap, Scan, Read LibGuide (https://libguides.fiu.edu/nfc).

Hence, a few smart posters had already been designed and placed around our library by the time we decided to use our rotating display space for the Harry Potter display. We created the display to capitalize on an increased interest in the boy wizard coinciding with the 20th anniversary of the publication of the first book in the series, then sprang into action to create our NFC e-resource cards to add to the magic.

Step 1: Selecting Materials

The Harry Potter display was a collaboration between the Web Services Librarian, bringing his expertise on NFC technology to the project, and one of the television and film subject librarians, bringing her expertise on Harry Potter and related media to the project in order to serve as the content curator. She selected the Harry Potter books and movies for the display as well as recommended fictional readalikes and various nonfiction works on witchcraft and wizardry, the sociocultural impact of the series, and fandom studies. Collaboration with a curator ensured relevant and appealing materials would be selected for the display, while freeing the Web Services Librarian to focus on the technological aspects of the project. The curator selected the materials to be included in the project, designed the physical display, and processed the print resources, while the Web Services Librarian designed the digital component of the display and created the NFC e-resource cards.

Step 2: Design a Template

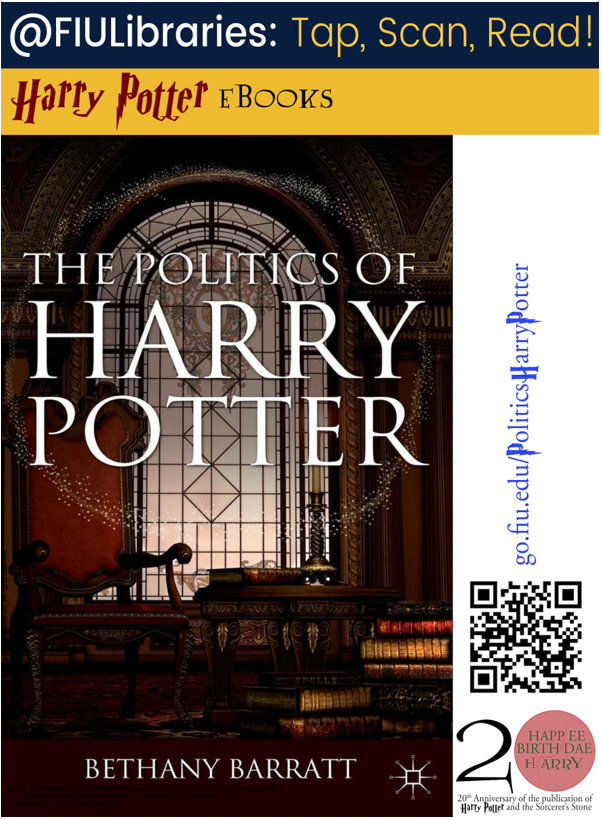

We used our existing @FIULibraries: Tap, Scan, Read template for the e-resource cards, as maintaining the same visual style across displays helps with brand recognition. In this template, a dark blue header with bold white text announces the project’s name while right below it a yellow background highlights the subcollection to which the poster belongs, for this display either “Harry Potter eBooks” or “Swank: Digital Campus Movies.” By using the cards in just one display, students therefore learn to recognize and use NFC technology throughout the library.

Figure 1. Header with project title and subcollection

Every NFC poster and e-resource card includes a brief set of instructions that mirror the wording “Tap, Scan, Read” to emphasize users should be able to obtain their resource in just a few simple steps. We purposefully crafted brief sentences for quick reading and easy implementation.

Figure 2. Back of e-resource card with instructions

For e-resource cards, a large portion of the real estate is devoted to the cover of the resource in order to help users recognize and identify the material presented. The NFC Tag is affixed behind the QR Code. Further, the NFC Tag, QR Code, and short URL are located together in the white space beside the cover to present all actionable triggers in the same place.

Figure 3. Body section of an e-resource card

Step 3: Secure the Permalink

It is important to use a trustworthy link that will not fail users after they have gone through the trouble of using an innovative delivery method. It is also critical that this link be their final stop, so the permalink should direct the user to the resource immediately, since users want to use the resource, not fiddle with record metadata. In the case of ebooks, the permalink should open to the cover page of that book. In the case of streaming video, the permalink should launch the video app and begin playing the movie.

Step 4: Create a Short URL

Short URLs allow the creators to present a memorable link to the more complex permalink, branding opportunities and usage statistics. FIU’s Division of External Relations offers a branded shortener to the university community, so we opted to use their services for this project. However, even an unbranded Goo.gl, Bit.ly or Tinyurl serves as a vast upgrade over daunting ILS generated URLs.

Step 5: Generate QR Code

Most URL shortening services also allow one to generate and download QR Codes from the new short URL. Our solution does not, so we used goo.gl to shorten the permalink and generate a QR Code for our cards. Statistics can be kept separate or added to the overall numbers depending on what we want to analyze.

Step 6: Program the NFC Tag

In order to program NFC Tags, you will need a mobile device with an NFC chip and an NFC Writer App. If you have access to the former, then the latter should be no problem. For the project, we have a dedicated Google Nexus 7 with an app called NFC Tools installed. For the tags, we have been using NTAG213 Stickers (25mm circle).

Once you have gathered the equipment, there are three simple steps to programming NFC tags: (1) Format, (2) Write, and (3) Secure.

First, format the tag to ensure that you are working on a clean slate. Our tags are reusable, so we have the option to reformat and reprogram tags from old displays and repurpose them. Formatting does not take long and can be viewed as a best practice first step.

Second, write to the tag. We choose to program the short URL onto the NFC tag, but there are several options that may be useful. For instance, a subject librarian may choose to program a virtual contact card, or the tag may launch a specific app, or WiFi configuration can be programmed right into the smart poster.

Third, secure the tag to discourage tampering. Without a deterrent, the mischief our students might play on our e-resource cards might rival that of the Weasley twins. NFC Tools allows you to either lock the tag or set a password. However, a locked tag cannot be unlocked, so we have decided to set passwords to have the option to repurpose tags later.

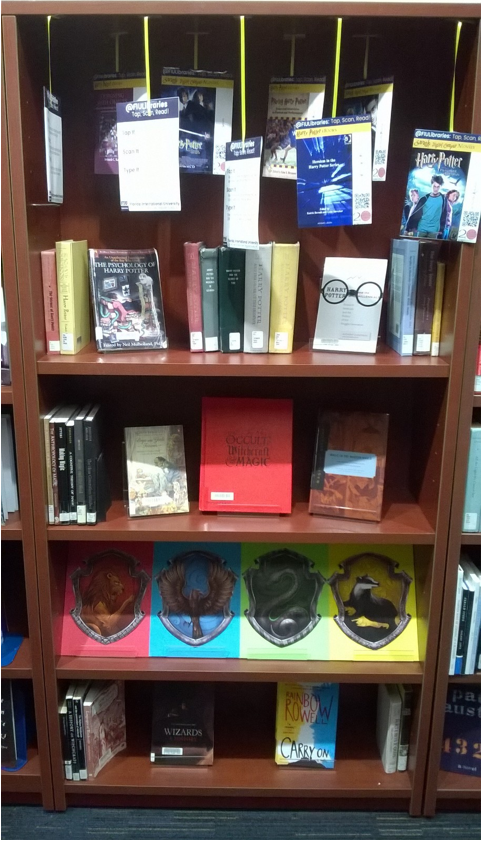

Step 7: Put It All Together

And now you are ready to press print, affix the NFC tag to the poster, and set your display out for both magical and muggle enjoyment. We chose to hang our e-resource cards from curled golden balloon strings so they hovered over the other curated materials like the floating candles over the Hogwarts Great Hall. In addition to creating visual intrigue, the cards could easily be pulled down this way for scanning, bouncing back up automatically to their original locations after use.

Figure 4. Front of a completed e-resource card

Conclusion

The Harry Potter display was active from June 2017 until the beginning of October 2017. It proved as popular as a Gryffindor vs. Slytherin Quidditch match from day one. Crowds of students often gathered around it and exclamations of delight were frequently heard from both the nearby Circulation and Reference Desks. The numbers backed up what our eyes beheld.

Figure 5. Picture of the completed Harry Potter display

The Impact

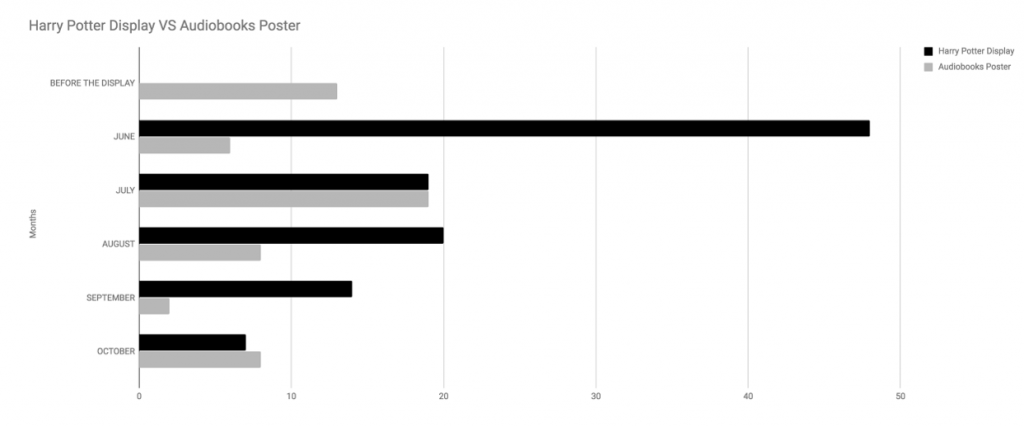

Over the display’s lifetime, it recorded 108 technological hits. The 48 hits in June constituted the bulk of interest in the e-resource cards and may be attributed to the display’s novelty. However, during the next three months, interest held steady at an average of 18 hits per month. October was on pace to match September, but the display was replaced with a new theme as scheduled.

During this same period, the nearby audiobooks poster garnered 43 hits, bringing the total @FIULibraries: Tap, Scan Read activity to 151 hits over the 5 month convergent lifespan of these displays. The audiobooks poster enjoyed a healthy average of 9 hits per month while the Harry Potter display was exhibited, an increase from the approximate 7 hits per month the audiobooks poster received in the two months it was available before the installation of the Harry Potter display. In the month of July, hits for the audiobooks poster (19) eclipsed the poster’s combined two month totals (13). While the Harry Potter display’s trajectory trended downward as the display aged, the audiobooks poster’s usage chart showed peaks and valleys during the same period.

Figure 6. Chart detailing the performance of the Harry Potter display versus the audiobooks poster.

Contributions to these numbers from the QR Codes was shockingly low for such a familiar medium. Hits contributed by the Harry Potter display QR Codes for the duration of the display accounted for just 7.4% of the total hit count. There were no reported hits from the QR Code on the audiobooks poster from the months of June to October.

The print materials in the display were highly used as well, with over a ten-fold increase in their circulation (collectively) compared to the same period in both 2015 and 2016. Books kept flying off the shelves as if charmed by Wingardium Leviosa, and continually had to be replaced with related items in order to keep the display populated. Seeing the display’s popularity, other librarians were encouraged to contribute to the display with their own related reading recommendations, increasing the variety of both the content and formats promoted over time.

Based on both the NFC and circulation statistics, it appears there was a novelty period for the display that lasted approximately three months, after which point the display seemed to start to lose its appeal. Throughout this period, however, the display not only brought attention to the materials included in this particular display, but also to the unrelated displays in proximity, such as the audiobooks poster. Thus, we believe one novel display in the area can stimulate interest in surrounding permanent displays. Fortuitously, this three-month period coincides with a semester for academic libraries and with a season for all libraries, so rotating just one display each semester or season may increase usage of all materials promoted in the area continuously without requiring constant labor.

Challenges

The high usage of the materials included in the display had a downside we were happy to experience: every time we returned to the display, there was less of it there than there was before. As discussed above, the frequent circulation of the books required continuous replacement. In addition, in their enthusiasm some students detached the NFC cards from their magical floating arrangement in order to handle them more easily, but this issue was easily resolved with the use of generous amounts of Spellotape. The cards were sturdy and, though a bit crumpled by the end of the three-month display period, of sufficient durability to withstand continual use.

The technology itself introduced a greater challenge initially. At the outset of the @FIULibraries: Tap, Scan, Read project, most devices in the market were incompatible with NFC technology. This presented an equity and fairness issue, and we did not wish to invest resources for a service that would only be accessible by a few. Consequently, in order to increase accessibility, we decided to relieve the problem by incorporating both QR Codes and a Short URL in the e-resource cards, as discussed above, so users on mobile devices or laptops without NFC could use the resources as well. All current and future iterations of this project will include these elements for inclusivity purposes, until improvements in technology make this workaround unnecessary.

In addition, since each vendor can modify access protocols for the resource, we had issues with a particular vendor’s “login to view” requirement. This requirement goes against the idea of instant access to the resource. Happily, this issue was negated once a merger took place and the challenging platform conformed their processes to a different standard that allows either IP or proxy authenticated users to read the resource instantly.

At the conclusion of the Happee Birthdae Harry display, we assumed there would be some correlation between the URL hit counts and usage statistics. Unfortunately, since we selected titles from various vendors and ebook platforms, we were unable to obtain consistent usage data for these materials. Further, while our overall streaming video statistics show that interest in the Harry Potter movies trended up during the display’s lifetime, we noticed some inconsistencies with the hit count depending on how the data was obtained. Thus, though hits can be a useful indicator of the popularity of displays, one cannot definitively depend on the accuracy of the numbers due to vendor, platform, and reporting inconsistencies, but it is possible to obtain a good idea of general trends.

Future Directions

The Harry Potter display served as a magical introduction to NFC technology for many of our students. The aforementioned Apple announcement of improved integration with both NFC technology and QR Codes in several models of the iPhone — all new iPhone models (8, 8 Plus and X) are fully equipped out of the box, and the 7 and 7s will be able to use advanced NFC functionality after their upgrade to iOS 11 — may lead to more widespread adoption as the technology enters mainstream use. According to our analytics data from July to October, students initiated more than 3 times as many sessions with devices running iOS than those running Android. However, our observations show that the QR Code was not heavily used. This may be due to the fact that until the recent Apple announcement QR Codes required a dedicated QR Code reader on iPhones, but this is no longer the case. Given tighter integration with the native camera on all iPhones that can be upgraded to iOS 11 and the high proportion of iOS users among our students, QR Codes may see a bump in usage in the future.

This display’s success, particularly the hit count numbers, shows there is interest in using this technology among students. It is important to note that the presence of the Harry Potter display drew attention to the nearby audiobooks poster, which benefited greatly from increased usage as a result of its proximity. This leads us to conclude the Harry Potter display may have acted as a Platform 9 3/4 to NFC-delivered content for our students. As we expand the service and continue producing Tap, Scan, Read products, we anticipate growing user familiarity to encourage extended use of this technology, helping us transfer library resources instantly from physical locations into our students’ hands.

References

Abram S. 2007. What’s in the pipeline? Part 2. What I watch. Internet@Schools [Internet]. [cited 2017 November 21]; 24(3):8. Available from http://www.internetatschools.com/Articles/Column/The-Pipeline/THE-PIPELINE-Whats-in-the-Pipeline-Part-2.-What-I-Watch-117993.aspx

Guevara S. 2012. A beginner’s guide to near field communication. Information Outlook [Internet]. [cited 2017 November 21];16(6):24-25.

Hoy MB. 2013. Near field communication: Getting in touch with mobile users. Medical Reference Services Quarterly [Internet]. [cited 2017 November 21];32(3):351-357. Available from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/citedby/10.1080/02763869.2013.807083?scroll=top&needAccess=true

Introducing Core NFC [Internet]. [updated 2017 Jun]. San Jose (CA): Apple, Inc., developer.apple.com/wwdc; [cited 2017 November 21]. Available from: https://developer.apple.com/videos/play/wwdc2017/718/

Yusof MK, Abel A, Saman MY, Rahman MNA. 2015. Adoption of near field communication in S-library application for information science. New Library World [Internet]. [cited 2017 November 21];116(11/12):728-747. Available from http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/full/10.1108/NLW-02-2015-0014

About the Authors

Christopher M. Jimenez (Hufflepuff) is the Web Services Librarian at the Green Library’s Department of Information and Research Services at Florida International University. He manages and promotes the @FIULibraries: Tap, Scan, Read project. ORCID: 0000-0001-9397-2850

Barbara M. Sorondo (Ravenclaw) is the Health Sciences Librarian at the Green Library’s Department of Information and Research Services at Florida International University, and serves as one of the department’s television and film subject librarians. She was an early adopter of NFC technology for library marketing and has curated several library displays on both health sciences and popular media topics. ORCID: 0000-0002-9930-6936

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply