By Joe Ryan and Josh Boyer

Introduction

GroupFinder is a system designed to help users working in groups let each other know where they are, what they are working on, and when they started. There are several ways to post to the GroupFinder system. Users can view GroupFinder posts inside of D.H. Hill Library (the main campus library at North Carolina State University) on large electronic displays (hereafter referred to as “eboards”), library kiosk workstations, the library web site, and the mobile web. GroupFinder is inspired by bulletin boards, a way many libraries have traditionally facilitated informal student meet-ups. It was designed and developed by NCSU Libraries staff from the Digital Library Initiatives and Research & Information Services departments.

Today, GroupFinder is a heavily used, highly visible system in an unusually busy and connected library. Tour guides often talk about GroupFinder as they showcase the library, and some students use it every week to set up meetings. A few years ago, however, GroupFinder was just an idea brought about by a set of observations: that the library is really busy, and that students in the library were heavy Facebook users.

Project History and Motivation

GroupFinder grew out of the creative burst of energy that accompanied the opening of the Learning Commons in March 2007. Like the myriad academic libraries that have opened Learning Commons (or Information Commons) in the last decade, we hoped to provide a more technology-rich and student-friendly environment. The Learning Commons in the D.H. Hill Library features over 100 desktop computers (PCs and Macs); printers; scanners; a poster plotter; laptop lending; other devices available for check-out such as cameras, GPS units, and Kindles; reference books; comfortable seating; group study rooms; a presentation practice room; rolling whiteboards; video games; and a service desk staffed by reference staff and student employees.

Library staff have worked hard to devise ways to help patrons find all these new tools and services. An early success in this effort was a set of Computer Availability maps. These maps display the up-to-the-minute availability of 103 computers in the Learning Commons on the 1st floor and another 108 computers on floors 2 – 9 (see http://www.lib.ncsu.edu/compavailability/web.php). With the Computer Availability maps displaying continuously on eboards throughout the library, students who need a desktop computer can quickly find one.

What else might students need help finding? Library patrons need help finding books, study rooms, specialty rooms like our Digital Media Lab, restrooms, vending machines — you name it, someone is lost in a library looking for it.

In the early days of the Learning Commons, Josh Boyer, Associate Head of Research and Information Services, and Tito Sierra, Associate Head for Digital Library Development, pondered another problem. In addition to considering what students were looking for in the library, they wondered who they were looking for. Patrons come to the library not just for the collections, equipment, and services, but to find each other. D.H. Hill Library is one of the most heavily used buildings on the NCSU campus. Hundreds and sometimes as many as 1,000 students are scattered throughout the library at any given time. Our 9 reservable group study rooms are nearly always full. We had observed students standing near the entrance, waiting for each other, trying to find each other using their mobile phones. Could we help them find each other? If we found a way to help our patrons connect, we could further the library’s role as academic heart of the campus.

The first effort was simple and cheap. We put a bulletin board on the Learning Commons website. We put it out there to see how students would use it and hoped it would be useful. We wondered if students would use it to find each other and arrange meetings. They did not. The bulletin board gathered useful feedback for a few months (mostly debates pro and con about the noise level in the boisterous and social Learning Commons), and then grew repetitive and argumentative. We abandoned the bulletin board idea.

We were trying to create an online social tool to help students find each other in the library. Online… social… college students — Facebook! It seemed so obvious — we needed to build a Facebook application. “The D.H. Hill Activity Wall,” as Sierra dubbed it, would be a brilliant custom Facebook app. We would plug in to the dominant social network of our time. Success would surely follow.

Sierra brought Joe Ryan, Digital Projects Librarian, into the conversation. By late 2008, Sierra and Ryan had a prototype Facebook app up and running. In early 2009, Ryan and Kim Duckett, Principal Librarian for Digital Technologies and Learning, took the app to a group of students in a Communications class. Their feedback was unanimous and clear — good idea, but don’t build it in Facebook.

When Boyer heard this, he was stunned and disappointed. What could possibly be wrong with the simple equation: online + social + college students = Facebook? Boyer and Duckett held a focus group of students to further test the idea of the D.H. Hill Activity Wall idea. Same result. Good idea, but don’t build it in Facebook.

The students told us we had correctly identified a need, but our solution was wrong. Yes, they told us, finding friends and classmates in the library was difficult, and yes, the library could certainly provide some kind of tool to help, but they could not imagine going to Facebook to find out where their group was meeting. “I don’t know,” one student said. “It doesn’t sound practical. It would be an extra step, an extra process.” Facebook is a social space for friends and peers. It’s not about studying, the students told us, and interacting with the library on Facebook feels uncomfortable and strange.

We gave up on the Facebook app. Going back to the drawing board, we held a series of one-on-one interviews with students in order to explore why they come to the library and how they find friends and study partners once they are here. The students described many contexts for meeting at the library — groups of friends relaxing, students meeting tutors, club meetings, etc. — but the activity they talked about most was group study for a class. Students described how they arrange, before or after class, or via email, a time to meet at the library. These study groups often include friends and also acquaintances from class whose phone numbers they do not have. So they meet at the appointed time near the entrance to the library, and there and then the problems begin. The group’s schedule is hostage to its most tardy member. Even groups of friends who all have each others’ cell phone numbers wait for each other at the entrance because the cell phone coverage of the D.H. Hill Library gets worse as you move beyond the entrance. Once all members of a study group have assembled, they search the library for a suitable place to study. In our crowded library, this often involves looking one place, then another, and maybe a third spot before settling down to study. This process is why would-be group members have to meet at the entrance in the first place — if they decide on a specific location ahead of time, it will likely turn out to be unavailable.

During these interviews, we mostly stuck to listening to students describe how they did group study. We did not spend time pitching our various ideas for the nascent, non-Facebook D.H. Hill Activity Wall. When we did hint, however, that any potential tool would probably post information to library’s eboards, students embraced the idea. One student, reflecting on the wandering that groups have to do to find a good place to study, said “Yes, you could post ‘We’ve moved to the 4th floor.'”

There is an important exception to students’ inability to plan a time and place to meet within D.H. Hill Library — 9 group study rooms. These rooms are reservable online. The popularity of these rooms is difficult to overstate. During desirable meeting times, the PM hours, they are booked nearly non-stop.

We imagined that the D.H. Hill Activity Wall would serve the study groups with unsettled plans — the “we’ve moved to the 4th floor” groups — more than those with reserved study rooms. As you will see below, we were in for a surprise.

Ryan got to work building a prototype of the new tool. After several design iterations informed by individual and group interactions with students, a prototype was ready for testing in October 2009. Ryan put the D.H. Hill Activity Wall on a computer kiosk in the main lobby of the library for in situ usability testing. Ryan, Boyer, and a usability consultant, Abe Crystal of MoreBetterLabs, Inc., offered students coffee and asked them to test drive the application. As always, students responded positively to the purpose of the tool, agreeing that it met a real need. “This definitely would be useful,” one said. “It’s pretty cool,” said another. Ryan’s prototype was more than halfway there. It worked. It was usable. The tests identified several minor user interface issues but validated the product’s functionality. While Ryan was making his last few tweaks, we rethought the name. D.H. Hill Activity Wall no longer captured what we were building. The tool was about a specific kind of activity, group study. Its job was to help people find their group. We decided not to over-think it: GroupFinder.

With final tweaks complete, GroupFinder launched on October 26, 2009. Would anyone use it? We put a large poster in the lobby next to the new kiosk workstation, and hoped. Hours passed. Would anyone use it? What if no one did? What if only a few people did?

Busy with these thoughts and philosophical musings about what “success” might be, we were too busy to notice that just after 1:00 PM, (in fact, at 1:08:37 EST), we had our first post. And it wasn’t even a staff member taking the new system for a test drive! It was, however, a student employee. He used GroupFinder for its intended purpose and told his group to check the eboards to find out where to go.

The next day saw its first official use by a non-library employee. In the days to follow, use trickled in. A post or less per day was the norm. What was happening? Boyer ended up in a conversation with a library student employee who made what turned out to be a revolutionary suggestion: what if you could post to GroupFinder directly from the online room reservation system? After all, the employee reasoned, when someone reserves a room, they already have to tell us who they are, when they will be here, and where they are–almost the same information GroupFinder displays.

Several weeks later, on November 30, 2009, integration work with the study room reservation system was complete. Now, when a patron reserved a room, a single check box labeled “Post to GroupFinder?” allowed easy access to the system. That same day, seven different students posted activities to GroupFinder.

Use increased steadily for the remaining few weeks of the semester. During that time, Ryan developed a mobile web version of GroupFinder that allowed both posting and viewing of activities. Early the next semester, Ryan refined the visual design of the various interfaces so that they shared a common branding and color treatment.

Since early 2010, the system has been in use in this state. Read on to find out how it works.

How it Works

Assuming that people are often reluctant to adopt new ways of accomplishing basic tasks like setting up group meetings, the GroupFinder team set a goal of having the system be extremely easy to use, both for the organizer of a study group and for the members of the study group who need to know the topic, time, and location of the group.

Creating a GroupFinder Post

The GroupFinder system supports activity creation via three venues: the main GroupFinder interface on the Libraries’ web site (http://www.lib.ncsu.edu/groupfinder), the online study room reservation system, and the Libraries’ mobile web site.

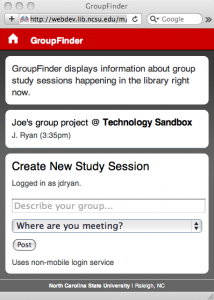

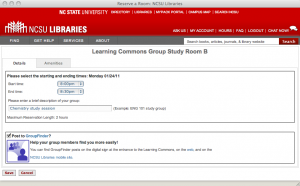

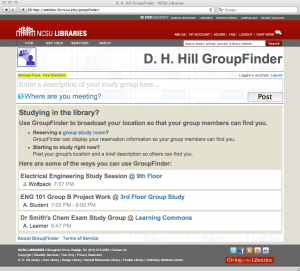

Creating a GroupFinder post on the main interface (Figure 1) takes just three steps. First, the user enters a short description of their study group in the large input box. Then, the user clicks, “Where are you meeting?”, which displays a list of locations in the building, sorted by floor. Figure 2 shows the dialog box and its use of small photographs to help users identify locations whose names may not be familiar. After describing the activity and its location, the user can then click the “Post” button. Once the user has successfully authenticated to the campus authentication system, the activity is displayed on all GroupFinder interfaces.

Posting on the mobile web interface (Figure 3) is similar to the main interface, except that the locations are represented in dropdown form instead of a dialog box. Again, after filling out the form completely, the user must authenticate, and the activity is displayed on all GroupFinder interfaces.

The most popular method of creating GroupFinder posts to date, however, has been via its tight integration with the NCSU Libraries study room reservation system. The NCSU Libraries uses phpScheduleIt, an open source reservation system, for scheduling of group study rooms in the D.H. Hill Library. The GroupFinder team modified the source code of phpScheduleIt to show an option on the reservation form to allow users to have their reservation information display in GroupFinder at the appropriate time (Figure 4). Users are required to provide a brief description of their activity and can only reserve a room if they can authenticate to the campus authentication system.

Posting to GroupFinder via the study room reservation system, the idea of the student employee mentioned above, has accounted for nearly 94% of posts. This surprised us, because we imagined there would be a great deal more use of GroupFinder to announce meetings in ad hoc contexts. Because of GroupFinder, we have a greater appreciation of students’ need to reserve group study rooms.

Viewing GroupFinder Posts

GroupFinder posts are visible in three places: the main GroupFinder web site (Figure 5) , the mobile web site (Figure 3), and on eboards. Each interface displays activities in reverse chronological order, with the newest activities at the top of the screen, and the oldest activities at the bottom of the screen . GroupFinder displays activities for a set length of time depending on where they were created. For activities posted from the main or mobile web interfaces, the activity displays for two hours, although users can end their own activities early if desired. GroupFinder displays activities that were created via the Room Reservation System starting fifteen minutes before the start of the reservation through the end of the reservation window.

Moderating GroupFinder Posts

During the project planning process, we were worried that, once undergraduates learned that they could post messages to eboards, abusive or offensive posts might be a problem. To that end, GroupFinder has an administrative interface where individual posts can be disabled by an administrator. To aid community moderation, any authenticated user can also report an offensive activity for review by the GroupFinder team. Once a user reports an activity, the activity is emailed to the team for review.

Fortunately, there have only been a small number of cases where the team has found it necessary to disable a post. Typically, Boyer checks the queue of activities that will display in the morning. Night staff at the Circulation Desk also have the ability to disable a post. In the past year, we have disabled fewer than ten activities, most of which were disabled because of expletives in the activity description.

Under the Hood

GroupFinder is a PHP application that uses MySQL for data storage. Visual effects in the user interface are supported by jQuery UI. The NCSU Libraries has released an open source (MIT license) version of GroupFinder that includes a web interface and an eboard display template. Because the study room reservation system code and the mobile web code depend heavily on other custom code in use at NCSU, they are not included in the open source release. The source code is available on Google Code at http://code.google.com/p/groupfinder/.

Usage

Since its launch on October 26, 2009, GroupFinder has displayed information on more than 3,400 group study sessions created by over 1,100 unique users. Because library usage patterns closely mirror the semester schedule, we will present numerical use data from the Spring 2010 and Fall 2010 semesters, and will conclude with an examination of the ways patrons are using GroupFinder. For purposes of this analysis, “semester” is defined as starting on the first day of classes and ending on the last day of final examinations.

Spring 2010 Semester Usage

Spring 2010 (January 18 – May 13) was the first semester where GroupFinder was available in its present form for the entire semester. GroupFinder displayed 1,316 posts by 495 unique users, an average of 2.7 posts per user. On the busiest day, April 20, 2010, GroupFinder displayed 30 posts. On that day, GroupFinder displayed at least one activity continuously from 10:45 AM until 12 midnight on April 21.

Fall 2010 Semester Usage

The Fall 2010 semester (August 18 – December 16) saw the heaviest use of GroupFinder to date. There were 1,611 posts by 639 unique users, an average of 2.5 posts per user. This semester’s usage reflects a 29% increase in the number of unique users and a 22% increase in the number of posts. On the busiest day, November 2, 2010, GroupFinder displayed 28 posts. On that day, GroupFinder displayed at least one activity continuously from 10:00 AM until 12 midnight on November 3.

Types of Usage

GroupFinder was originally envisioned to be a system for students to notify each other about planned and ad hoc study sessions within the library space. And, indeed, this is its most popular use. Since its launch, however, GroupFinder users have made the system their own by adapting it for a number of alternative uses. Below are some rough categories of usage, each with example posts from the system. For privacy, the names of the posters are not reproduced here.

Class-oriented study groups

* ENG 261 (October 25, 2010, 6:30 PM – 7:30 PM)

* CSC302 Numerical Methods is really frustrating :( (March 9, 2010, 12:30 AM – 2:30 AM)

Person-oriented study groups

* Eric’s Tutoring (October 26, 2010, 2:30 PM – 3:30 PM)

* alonso’s study room (May 3, 2010, 12:00 PM – 12:30 PM)

Campus organization meetings

* Campus Farmers Market at NCSU (September 27, 2010, 7:00 PM – 9:00 PM)

* HOSA Executive Board Meeting (April 4, 2010, 8:00 – 8:30 PM)

Organizationally oriented study groups

* Interested Gentlemen of Lambda Theta Phi (November 5, 2010, 1:30 PM – 3:00 PM)

* Theta tau study hall (February 2, 2010, 9:00 PM – 11:00 PM)

Religious use

* Christians on Campus Bible Study (September 16, 2010, 5:30 PM – 7:30 PM)

* Tajweed (January 28, 2010, 5:00 PM – 7:00 PM)

Wildcard use

* KITTYKAT’s getting PHYSICal (October 27, 2010, 6:00 PM – 8:00 PM)

* Blink 182 Fan Club! (September 8, 2010, 8:30 PM – 10:30 PM)

* Egg Fryin’ on a Rock (April 5, 2010, 2:00 PM – 4:00 PM)

* Star Warriors (January 30, 2010, 3:00 PM – 5:00 PM)

What Users Are Saying

On November 29, 2010, we sent out a link to a web-based survey to every single person who had posted to GroupFinder since the start of the Fall 2010 semester. 77 of the 591 users completed our survey, a response rate of 13%.

Our motivation for surveying our users was simple: we designed GroupFinder to make it easier for library patrons to meet up at the library in order to get group work done. We asked questions about what role in the group the respondent typically plays (organizer or member), their perception of GroupFinder’s utility, whether GroupFinder prevents them from having to wait in the lobby for latecomers, questions related to mobile phones’ utility to their meet ups, ways they typically organize meetings, and, finally, how we could make GroupFinder more useful to them.

Do our users find GroupFinder useful? 46% of respondents rated GroupFinder “very useful” in their efforts to set up group meetings. An equal share of respondents rated GroupFinder “somewhat useful,” and 9% of respondents rated GroupFinder as “not very useful.”

Did we achieve our goal of reducing the amount of time people have to wait in the lobby for group members who are running late? 73% of respondents said that we did.

So far, so good! But of course most of our use comes from posts made via the Room Reservation System. We asked if respondents had thought about using the standard posting interface? 80% of them said that they hadn’t even thought about it. One respondent commented, “I didn’t know you could use it outside of the reservation system” while another said, “I tried to do this once, but could not figure it out.”

The question that yielded the most interesting responses was a free-form question, where we invited respondents to suggest ways to make GroupFinder more useful. We received many interesting suggestions, ranging from adding the ability for users to add their own start times on the web interface, to email and/or text message reminders that a meeting was about to start.

Overall, the survey data suggest a need to promote GroupFinder generally to increase awareness and usage. Also, as confirmed by use data, there is a need to promote the ability to use GroupFinder outside of the study room reservation system. Some survey respondents did not seem to be aware that GroupFinder was a separate system from the Room Reservation System, which presents an interesting question: should we work to merge the two systems further and market them jointly as “GroupFinder,” or should we work to differentiate the two systems further?

Conclusion

Although GroupFinder started out as a few casual observations about a busy library, lots of group activity, and the popularity of Facebook, it has grown into a multi-faceted and heavily used tool that is helping to change how patrons use library spaces. We consider it our own take on location-based social networking. Compared to the location-based services of Twitter, Facebook, Foursquare, Gowalla, and others, GroupFinder is hyper-local, limited to one building!

The success of GroupFinder owes a lot to our willingness to listen to our users and to take risks. If you are interested in pursuing a similar project at your library, we urge you to begin with the users and their needs instead of a desired tool or technology. By following this process with GroupFinder, we believe that we have built a useful system.

About the Authors

Joe Ryan (josephdryan@gmail.com) is the Humanities Research Associate at UNC Chapel Hill Research Computing. He was the Digital Projects Librarian at North Carolina State University until February 2011.

Josh Boyer (josh_boyer@ncsu.edu) is the Associate Head of Research & Information Services at North Carolina State University.

The Limits of Facebook « Fail!lab, 2011-04-12

[…] I saw some evidence from the good folks at NCSU to back up my gut […]

CBS Bibliotek Blog – Innovation & Ny Viden » Blog Archive » Nyt nummer af The Code4Lib Journal, 2011-04-14

[…] GroupFinder: A Hyper-Local Group Study Coordination System […]