Background

Colorado College’s Tutt Library is a small, urban, academic library serving the needs of over 2,000 students along with faculty and staff in Colorado Springs, Colorado. As a member of the Colorado Alliance of Research Libraries, a consortium of academic and public libraries in Colorado and Wyoming, we participate in a union catalog comprising the collections of our member institutions. Our Islandora Institutional Repository is also hosted through the Colorado Alliance’s repository service. We operate our own instance of III’s Millennium ILS, however. Like most academic libraries, our material budgets have shifted from physical to electronic resources and, as a consequence, we are doing more batch loading of MARC records for these electronic resources and less original or copy-cataloging of print material.

With the quality of vendor-supplied MARC records varying considerably, the old workflows to manipulate and load records into our legacy ILS were often long and laborious processes. By scripting the manipulation of these MARC records with Python and the pymarc Python module [1], and with a web front-end built in Django, we brought considerable time savings to our cataloging staff. This led to a second Django project that enabled senior students to self-submit their thesis or final essay, along with any supporting datasets, to our digital repository.

A parallel effort was started as we looked at various commercial and open source options for a new discovery layer. Given monetary and resource constraints, along with the worry of maintaining multiple codebases in different programming languages and environments, the library decided to fork Kochief, a Django-based discovery project. This decision led to the release of Aristotle, the Tutt Library discovery-layer project available on Github under the Apache 2 open source license [2].

In 2011, we started to explore using Redis, a popular NoSQL technology, to represent bibliographic and operational information. This research led to the FRBR-Redis datastore project that was the topic of a 2012 Code4Lib presentation [3]. Using the Library of Congress Bibliographic Framework Initiative’s “A Bibliographic Framework for a Digital Age” [4] as starting, high-level requirements for the FRBR-Redis datastore, we tested the suitability of using Redis with over 850 unit tests representing MARC21, MODS, and VRA metadata structured as FRBR Work-Expression-Manifestation-Item entities with a variety of Redis data primitives.

One of the trends highlighted at the 2012 Code4Lib conference was the growing importance of mobile devices, both in usage by library patrons, and in the limitations and opportunities presented by developing applications. This caused us to rethink how we offered access and management to bibliographic information from a desktop/rich web “discover” model to a simplified mobile app user interface used in mobile and tablet native applications such as Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android operating system. We started experimenting with Twitter’s Bootstrap support for responsive web design to build simplified HTML5 apps that were much closer to the design aesthetic of a mobile and tablet application. The first app we released was a call number app that provides an embedded widget for our discovery layer as well as a standalone app targeted for mobile and tablet devices but fully usable by modern desktop web browsers. This app was the beginning of the Aristotle Library Apps project [5] and can viewed online at http://discovery.coloradocollege.edu/apps/call_number/.

Since 2011, we continued to monitor the modeling work done by the Bibliographic Framework Transition Initiative. As we became more experienced with Redis, the initial implementation of a Redis FRBR datastore, with a single Redis instance using multiple databases, wasn’t as flexible as having each each of the first group of FRBR entities (Work, Expression, Manifestation, and Items) run as separate Redis instances on different ports on the same server. In September 2012, Sally McCallum, in an IGeLU presentation [6], offered the first glimpse of a new bibliographic model she referred to as MARCR, for MARC Resource. This new model supports RDA and FRBR but the core entities have been whittled down to four: Work, Instance, Annotation, and Authority. Because of Redis’s flexibility, we were quickly able to modify our existing FRBR Redis datastore key structure to follow this new model using RDA. A primer on this new model was published in November of 2012 [7], with the name changed to BIBFRAME and minor changes made to McCallum’s introduction from September. Namely, the Work entity became Creative Work and the namespace for the model was formally set as BIBFRAME. The BIBFRAME Redis datastore is now a separate open source project licensed under the GNU General Public License 2 and includes documentation, Redis server configuration files for each of the BIBFRAME entities, and LUA server-sides scripts [8].

More about Redis

Redis, a key-value datastore, is one of the many new NoSQL data technologies that offer alternative models for data representation and use. Redis supports data persistence in two ways: an RDB mode that saves the dataset at periodic intervals, and an AOF mode that saves the dataset with every write operation. While there are advantages and disadvantages to each approach [9], most libraries could employ a combination of RDB mode for bibliographic records and AOF mode for library transactional data like circulation statistics.

Redis is fundamentally different from the flat-file structure of a MARC record and the relational databases of more traditional library systems. The flexibility of Redis allows for the rapid development of multiple apps by supporting different information schemes and structures within a single datastore. The manner in which a Redis key is constructed allows for the embedding of semantic or heuristic information about the data structure in its naming structure. Redis assumes that related data use a key naming pattern, and even provides a global function to increment the key ID.

Another important design consideration when using Redis is the type of data primitive to associate with a key. The simplest value is an atomic string. The Redis list is a collection primitive which stores unordered and duplicate string values. The Redis set stores unique string values, while the sorted set assigns a sort weight to each value. If a weight of 0 is used in a sorted set, Redis does a lexical sort based on the string values in the set. The last Redis data primitive is a hash. A Redis hash associates multiple sub-keys with a single Redis key and with the HGET command returns the value associated with that sub-key.

Redis is not a relational database and it would be suboptimal to attempt to replicate an RDBMS. In Redis, the key is the fundamental structure, not a table-row as in an RDBMS. Redis keys can also serve as a string value for other keys in the datastore, providing a sort of crude SQL JOIN, but offering more flexibility in representing relationships between keys in a manner that would be difficult or impossible to replicate in an RDBMS. The downside is that referential integrity between different tables is not built into Redis. Eventual consistency can be achieved either through application logic or through strategies involving a combination of Redis server commands.

The Redis string, set, sorted set, list and hash data primitives all offer different ways to represent library information in the Redis server. Redis also provides a number of server and primitive-specific commands that ease application development, including EXIST and TYPE. For the EXIST command, a string is passed in as a parameter and a boolean is returned confirming whether the string is a key in the datastore. The TYPE command, when passed in a key string, returns the type of Redis data structure that is represented by the key or a null value if it doesn’t exist.

For large datasets that may not fit into RAM, the lead developer on the Redis project, Salvatore Sanfilippo, recommends presharding [10] to break up the datastore among different Redis instances. The naming schema used by the Aristotle Library Apps and BIBFRAME Datastore project can easily support presharding for use in large collections, though for the time being, a single Virtual Machine with 4G of RAM is more than sufficient to run all of Colorado College’s BIBFRAME Datastore Redis instances. The following graphic shows our Colorado College BIBFRAME Datastore set-up.

Figure 1. Colorado College’s BIBFRAME Datastore Setup

Figure 1. Colorado College’s BIBFRAME Datastore Setup

The Evolution of a Native Bibliographic Redis Datastore

The first iteration of a Redis bibliographic datastore used a naming schema based on FRBR and RDA, using a notation similar to XML namespaces to create a collection of keys to represent values and relationships with other entities in the datastore.

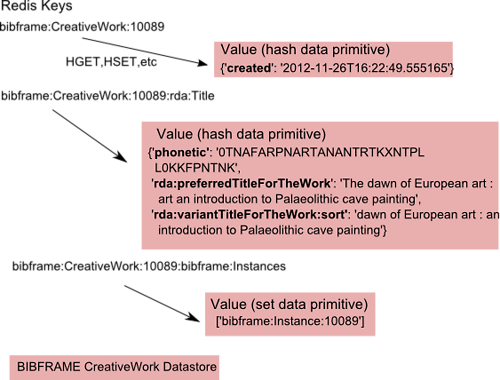

For example, in the Aristotle Library Apps project, RDA Core FRBR entities and attributes are extracted from MARC records following the MARC-to-RDA mappings provided in the ALA’s RDA Toolkit [11] that are then organized into Redis key collections following a pattern that maps to BIBFRAME linkable information resources like Creative Work, Instance, Authority, and Annotation. The figure below shows one such BIBFRAME Redis key collection for a CreativeWork’s RDA:Title with supporting Redis keys for that entity. The phonetic, rda:variantTitleForTheWork:sort subkeys and subvalues in the bibframe:CreativeWork’s rda:Title support Title searches by various apps and Colorado College’s Discovery Layer.

Figure 2. Example of Bibliographic Redis Keys and Data Primitive Values for a BIBFRAME Creative Work’s Title

Figure 2. Example of Bibliographic Redis Keys and Data Primitive Values for a BIBFRAME Creative Work’s Title

The BIBFRAME Datastore can support other metadata formats and values as well. Continuing the previous example, if we wanted to use MODS or Dublin Core instead of RDA, the BIBFRAME Datastore key could look like bibframe:CreativeWork:10089:mods:titleInfo with each of the MODS titleInfo sub-elements as hash key-value pairs for an individual CreativeWork. Likewise, a Redis key like bibframe:CreativeWork:10089:dc:title could be either a simple static string or a HASH like the current rda:Title key used in the current iteration of the BIBFRAME Datastore project. We could even have all three (or as many different keys as desired) exist in the same Redis datastore instance. The design of the Redis key’s structure is through convention and convenience with an effort to be explicitly descriptive of the data that is returned by Redis without being too verbose.

Meanwhile, financial information, such as material orders and invoice information stored in our ILS, is extracted and added to the Redis datastore for reporting and budget forecasts. We even store the library hours as a Redis string for use in a standalone app and as a JSON data feed for our discovery layer.

Redis datastore interactions are abstracted via Python classes, which are built with the redis-py module [6]. If the app developer needs custom data storage or extended Redis functionality, Python custom classes can extend existing classes through direct manipulation of the datastore.

HTML5, Responsive Web Design, and Twitter Bootstrap

While native apps generally run faster and more closely follow the recommended user interface guidelines for their respective platforms, the Tutt Library does not have the resources to maintain multiple app development environments. Thankfully, with evolving web standards and protocols, coupled with the development of CSS and JavaScript libraries, fast and easy-to-use HTML5 apps can be created that are more universal and can run on multiple mobile and tablet platforms as well as on personal computers running more modern web browsers that support HTML5. This is the goal of responsive web design, as expressed in the original article on A List Apart:

Rather than tailoring disconnected designs to each of an ever-increasing number of web devices, we can treat them as facets of the same experience. We can design for an optimal viewing experience, but embed standards-based technologies into our designs to make them not only more flexible, but more adaptive to the media that renders them. In short, we need to practice responsive web design. [7]

The Aristotle Library App project uses the popular web framework Bootstrap as the basis for the user interfaces that respond and adjust for different client devices and displays. It is prohibitively expensive and impossible for a small library with limited staff and resources to test out apps on all of the different platforms, web browsers, and devices used by our users. By focusing on the most popular and available devices in the library (Windows 7, Macintosh, iOS, and some Android phones and tablets), the Tutt Library targets specific functionality needed by its patrons and staff. The design intention of this HTML5-based app development environment is that creating a new app should be roughly equivalent in difficulty to building a simple website leveraging librarian and staff’s pre-existing competencies with such tools as Dreamweaver and content management systems. While there is training involved in educating staff about Bootstrap and HTML5, the training burden and requirements for app development is considerably less than if the library tried to develop native apps for the iOS and Android environments.

Access and Discovery Apps

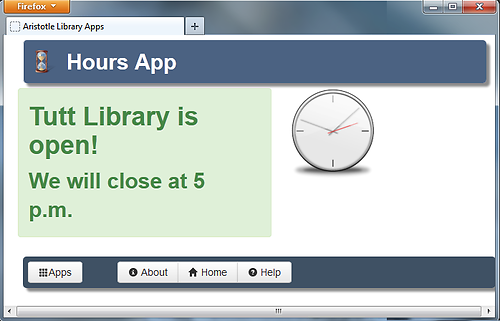

The majority of apps in the initial Aristotle Library App project are categorized as Access and Discovery Apps, which allow users to find and access the library resources and more general information about the library. Access and Discovery Apps broadly address the generic tasks by users to find, identify, select, and obtain resources as expressed in the FRBR specification [14]. Also included in this category, the Tutt Library’s Hours App informs a patron if the library is open or closed. While not bibliographic in nature, the Hours App addresses one of the top questions the Tutt Library receives from patrons.

The Call Number App

Figure 3. Screenshot of the Call Number App

Figure 3. Screenshot of the Call Number App

The Call Number App was the first app released, and served as the catalyst for the entire Aristotle project. As we worked on the discovery layer, another librarian was inspired by a feature in Stanford University’s Searchworks (built with Blacklight and Hydra) that allowed a patron to see which call numbers were near each other in the library’s stacks. While investigating Stanford’s implementation based on Solr, we realized a simplified data model could be used with Redis. To create the type of sorted indexes needed for this app, normalized Library of Congress, SuDoc, and local call numbers were added as weights to Redis sorted sets. Once we had embedded the Call Number App into the discovery layer, we explored the further development of dedicated, simplified apps for common searches. These independent apps could be used in larger systems, like the discovery layer or the library’s website, through the use of JSON APIs and raw HTML.

Library Hours App

Figure 4. Screenshot of Library Hours App

Figure 4. Screenshot of Library Hours App

When the college adopted a CMS incapable of building a dynamic feed of the library’s hours of operations for the library’s homepage, we felt that a dedicated app with a JSON feed and hours data stored in Redis would work instead. The Library Hours App stores dates and hours in a string using Redis bit operations commands. Each day has a unique key with the following pattern: “library-hours:YYYY-MM-DD”, with the value being a 96-bit string with each bit representing a quarter hour with bit offset 1 representing 00:00 to 00:14, bit offset 2, 00:15-00:29, etc. for each quarter hour of a twenty-four hour day. Bits set to zero (the default) means the library is closed, the bit set to 1 means the library is open for that quarter hour.

To see if the library is open, the Hours App queries the library’s operational Redis datastore by using a Redis GETBIT command as demonstrated in this code snippet from the Hours App’s redis_helpers.py [15]:

def is_library_open(question_date=datetime.datetime.today(),

redis_ds=redis_ds):

"""

Function checks datastore for open and closing times, returns

True if library is open.

<br/>

:param question_date: Datetime object to check datastore, default

is the current datetime stamp.

:param redis_ds: Redis datastore, defaults to module redis_ds

:rtype: Boolean True or False

"""

offset = calculate_offset(question_date)

status_key = question_date.strftime(library_key_format)

return bool(int(redis_ds.getbit(status_key,offset)))

The patron user interface for the Hours App displays a simple message with the library’s current hours. If the library is closed, the app displays the next available date and time when the library is open. With 365 keys per year, one for each day, this Redis structure easily supports the requirements of the Hours App administrative user interface, allowing authenticated library staff to add or modify the posted hours.

Productivity Apps

The second category of apps is for productivity, developed to either manage or report on resources in the collections. These apps require the user to first authenticate, then, depending on the app and the user’s authorizations, allow for the manipulation or reporting of library information, which includes the native BIBFRAME entities in the datastore. In the Orders App, order records were imported from Tutt Library’s legacy ILS into the FRBR Redis datastore. By doing so, we freed this information from the proprietary ILS vendor that tightly binds order information to the MARC bibliographic record (even going so far as to create custom 9xx fields for order information). By separating the order information into Redis sets with each invoice and order as distinct Redis keys, visualizations and budget reporting became much simpler. Before we had this tool we would have to export this data from the ILS and extract the data from the MARC21 record, then clean it up before importing it into Microsoft Excel for analysis of this critical aspect of library operational information.

We have also developed a productivity app for a collection of Fedora Commons utilities used by library staff to move objects around in the digital repository, ingest batches of objects, and apply a metadata batch update to one or more Fedora objects. While this app does not directly use the BIBFRAME entities, it has streamlined the workflow of staff in the library who work with the digital repository. The Aristotle Library Apps project is flexible enough to accommodate workflows with other library systems, like our Fedora Commons digital repository.

Roadmap for the Aristotle Library App Project

The Tutt Library uses its Call Number, Hours, and Discovery apps to augment the library’s website and discovery layer. These are publicly available, along with the Article and Book Search Apps, at http://discovery.coloradocollege.edu/apps/. The same JSON interface that the Call Number App uses to populate a shelf-browser is also used in the record view in the discovery layer. The Hours App provides an embedded HTML snippet for inclusion in various locations in the library’s website.

The next wave of app development will focus both on improving local workflows for such library services as material check-out, course reserves, and collection inventories, as well as improved discoverability of resources from other institutions through shared BIBFRAME Redis datastores. In keeping with an agile software development philosophy, each app should be simple enough to design, implement, and start testing within a three-to-four week sprint, which nicely coincides with the current academic block calendar at Colorado College.

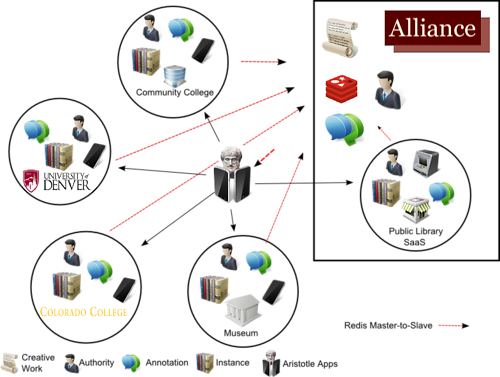

Peer-to-Peer and Consortium Union Catalogs

Concern over interoperability was brought up as a challenge to any radical technology change as the Tutt Library moved to an app model. The regional Colorado Alliance of Research Library’s Prospector union catalog, in which Colorado College is both an active lender and borrower, supports the college’s block plan, where students take intense, 3 1/2 week courses for college credit. With students needing research material promptly, Tutt Library strives to deliver to students, faculty, and staff as promptly as possible, preferably under 72 hours. The Prospector-based ILL service is critical to meet this tight deadline for materials. Any replacement or legacy ILS cannot diminish that service. Our plan to tackle these challenges involves an incremental approach, starting off with BIBFRAME datastores shared by just two institutions before increasing the scale to a consortium or regional scale.

Figure 5. Multiple Institutions Peer-to-Peer BIBFRAME Datastores

Figure 5. Multiple Institutions Peer-to-Peer BIBFRAME Datastores

We are currently in the early stages of prototyping a peer-to-peer BIBFRAME Datastore with the University of Denver’s Penrose Library. As the above diagram illustrates, in this early exploratory work Colorado College and the University of Denver each have their own Redis master running in their respective, local virtual machine environments. Each institution also has local Redis slaves of the other’s Creative Work, Authority, and Annotations that sync up with their corresponding master. Our intention is to test the usability of a shared BIBFRAME Redis-based union catalog with two institutions to prepare for scaling up to a consortium-level service.

Figure 6. Design of a Consortium BIBFRAME Datastores

Figure 6. Design of a Consortium BIBFRAME Datastores

Maintaining record-level interoperability should be relatively easy in the Library App Portfolio as long as the MARC utilities and productivity apps are in active development. The challenge is in integrating material requests and real-time circulation status into the proprietary system the Alliance currently uses for the Prospector. A strength of Redis is its ability to store and serve large volumes of data, as it has done for sites such as Github, Engine Yard, Craigslist, Disqus, and Stack Overflow [16]. The library is in early discussions with the Alliance about expanding the Aristotle Library Apps project to scale for millions of records.

Some interesting network topologies for bibliographic information may be possible when using Redis as the underlying datastore and FRBR/RDA as the organizing principle. For example, the Alliance may host the shared Work and Expression datastores, then subscribe to Manifestation and Item datastores managed and hosted locally at each institution, at the Alliance, or at a commercial cloud provider. Each institution could also use the Alliance’s hosted Work and Expression datastores in their own Access and Discovery Apps.

To support the increased scale of a consortium or regional BIBFRAME Redis ecosystem, we are closely following Redis Cluster, a sub-project of the Redis open source project. Redis Cluster offers a distributed and fault tolerant [17] environment for very large and distributed data nodes that matches well with our peer-to-peer and consortium-level BIBFRAME datastores. Redis Custer is under active development, with the developers planning a stable beta release in 2013. The library and the Alliance are also exploring grant opportunities to fund the development and support for a new bibliographic datastore that will scale to hundreds of millions of FRBR entities.

Notes

[1] pymarc. Available from: https://github.com/edsu/pymarc

[2] Aristotle Discovery Layer Project. Available from: https://github.com/jermnelson/Discover-Aristotle

[3] Nelson J. NoSQL Bibliographic Records: Implementing a Native FRBR Datastore with Redis. Code4lib 2012, Seattle, Washington. Available from: http://discovery.coloradocollege.edu/code4lib

[4] A Bibliographic Framework for the Digital Age. October 31, 2011. Available from: http://www.loc.gov/marc/transition/news/framework-103111.html

[5] Aristotle Library Apps Project. Available from: https://github.com/jermnelson/aristotle-library-apps

[6] McCallum, S. Bibliographic Framework Initiative Approach for MARC Data as Linked Data, September 13, 2012. IGeLU Conference Presentation. Powerpoint available at: http://igelu.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/IGeLU-sally-McCallum.pptx

[7] Miller, E., Ogbuji, U. and K. MacDougall Bibliographic Framework as a Web of Data: Linked Data Model and Supporting Services. November 11, 2012. Available from: http://www.loc.gov/marc/transition/pdf/marcld-report-11-21-2012.pdf

[8] BIBFRAME-Datastore project. Available at: https://github.com/jermnelson/BIBFRAME-Datastore

[9] Redis persistence. Available from: http://redis.io/topics/persistence

[10] Redis Presharding. Available from http://antirez.com/post/redis-presharding.html

[11] ALA’s RDA Toolkit Mappings. Available with subscription at: http://access.rdatoolkit.org/document.php?id=jscmap1]

[12] redis-py. Available from: https://github.com/andymccurdy/redis-py/

[13] Marcotte E. Responsive Web Design. A List Apart. May 25, 2010. Available from: http://www.alistapart.com/articles/responsive-web-design/

[14] Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records. International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. December 26, 2007. Available from: http://archive.ifla.org/VII/s13/frbr/frbr_current2.htm

[15] From the Aristotle Library Apps’s Project https://github.com/jermnelson/aristotle-library-apps/blob/master/hours/redis_helpers.py

[16] Who’s using Redis? Available from: http://redis.io/topics/whos-using-redis

[17] Redis cluster Specification (work in progress). Available from http://redis.io/topics/clster-spec

About the Author

Jeremy Nelson (Jeremy.Nelson@ColoradoCollege.edu) is the Metadata/Systems Librarian at Colorado College. He is responsible for ensuring that the Tutt Library technology that students, staff, and faculty at Colorado College depend on is available when they need it both on and off campus. He is also responsible for the cataloging department, ensuring that electronic and physical material acquired by the library is cataloged correctly and is positioned for future further use.

New Issue Alert: The Code4Lib Journal (Issue 19) is Now Online | LJ INFOdocket, 2013-01-15

[…] Building a Library App Portfolio with Redis and Django […]

Jurnal Media Syariah – Building a Library App Portfolio with Redis and Django, 2013-03-09

[…] By scripting the manipulation of these MARC records with Python and the pymarc Python module [1], and with a web front-end built in Django, we brought considerable time savings to our cataloging […]