by MJ Suhonos

History

Scholarly practice has, for decades, used a set of discipline-centric bibliographic styles (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) to codify the metadata elements in reference lists, through specific typographic and punctuation conventions. One of the most time-consuming and repetitious aspects of scholarly publishing is the validation and correction of this information. Generally, copyeditors must manually inspect each element of a citation and compare it visually to a record retrieved through an online indexing service.

With the advent of word-processing software and the Internet, a number of reference-management applications have appeared. Historically, this software has been proprietary and expensive, averaging from $100-300 for each copy installed [1]. More recently, inexpensive alternatives have arisen, such as the open-source, browser-based Zotero [2] and low-cost, web-based RefWorks [3]. Although these applications have given authors the ability to store and edit citations, they typically have very limited ability to search online citation indexes or export citations in a standardised, structured XML format.

As a result, there are a number of challenges for authors trying to manage their personal bibliographies and ensure an accurate and well-formatted reference list. Copyeditors, in turn, are constrained by their ability to read the reference format supplied and by their access to online databases for validating citation data.

Why Lemon8-XML?

In 2000 PubMed Central (PMC) was launched as a “free digital archive of biomedical and life sciences journal literature” [4]. The growth of PMC and similar archives led to a need for fully-structured documents containing not only indexing metadata, but marked-up content of the entire article, including bibliographic citations.

Although NLM maintains a rigorous review process for inclusion in PMC, there is also a substantial technical challenge involved in generating fully marked-up XML for complete journal articles. Commercial products and services are available for this purpose, but they tend to be very expensive, as with Inera’s $10,000 eXtyles software [5], or involve a pricey consulting contract for typesetting services. In addition, this work is often done manually or by outsourcing to workshops in developing nations, causing the quality to vary from vendor to vendor. In 2003, CrossRef, a collaborative reference linking service for scholarly articles using the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) system, added a fee of $0.22 per article, per year, for publishers who did not (or could not) provide fully-structured reference lists with each article they deposited in their system [6].

Open-access journals and small publishers in this situation find themselves in a difficult spot: they can’t afford the expensive services to get into the most prevalent indexes and archives, yet inclusion in those services would undoubtedly increase their exposure, academic impact, and for commercial journals, revenue. There is clearly a need for a low-cost, easy-to-use, software application that would lower the technical and financial barriers for journals seeking inclusion in these services.

The Public Knowledge Project (PKP) created Lemon8-XML (L8X) as a companion to its successful journal management software, Open Journal Systems [7]. The goal of L8X is to provide a freely-available, web-based article editor that gives users the ability to generate fully NLM-compliant XML with minimal effort, and provide assistance with correcting article and citation metadata. L8X is built upon common LAMP technology, and is currently being used by at least one journal in production [8].

Citation Parsing and Online Indexes

A number of research projects, including Paracite [9], Freecite [10], and Parscit [11], have attempted to create software which, based on established citation styles, can extract the requisite metadata elements in a way that is tolerant to aberrations and errors. At the same time, there has also been a rapid rise in the number of freely-available online indexes, such as OAIster [12], CiteSeer [13], and ISBNdb [14], that provide web-based search APIs and well-structured indexing metadata in XML response format.

The intent of L8X has been to, wherever possible, integrate the results of these efforts in an extensible manner. By building on the work of others, we can focus on making their systems and data more accessible to authors and copyeditors as efficiently and user-friendly as possible. In this way, we are helping to disseminate the citation parsing algorithms, increase visibility of the online indexes, and provide a pragmatic combination to automate the work that is already being done manually.

System Design

L8X is broadly designed as an application to assist in creating structured markup for an entire scholarly article, not just reference lists. The scope of the software also includes semi-automatic detection of article sections, figures, tables and metadata. Among the library and publishing communities, however, it has been the citation parsing and editing features which have garnered the most attention. The general approach involves the following steps:

- identify a portion of text that represents a formatted citation

- parse this text into discrete metadata elements

- identify the genre of the citation (journal article, book, etc.)

- search available databases for a full record of the citation

- provide a measure of estimated accuracy in parsing and searching

- provide an intuitive user interface to manually inspect the results at each step

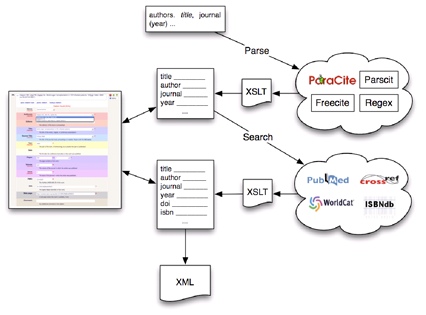

As can be seen in Figure 1, this is essentially a two-stage process: parsing and searching (“lookup”). The user interface is provided to allow editors to apply their knowledge and interject their corrections during the process if they choose, or it can be used to enter and edit a citation entirely manually – the parsing and lookup functions are assistive and optional. Likewise, by setting a threshold for “scoring” the accuracy of the parsing and lookup stages, an editor can choose to automatically process an entire reference list without using the user interface whatsoever.

Parsing and searching functionality is provided to L8X by way of “components” — essentially, plugins for accessing a particular parsing algorithm or online citation index. Each plugin is tailored to the API of the specific system it is contacting, including providing any authentication keys or schema mappings required to get data between L8X and the corresponding service accurately. By using this approach, new services can be added to the system by developing a new plugin and installing it. Similarly, journals or organizations can develop or maintain their own plugins as appropriate, and choose whether or not to release them, and under what terms if they choose so.

Figure 1. System design and data flow. [View full-size image]

The guiding design principle behind this approach has been to minimise the amount of work required by the editor, not eliminate it altogether; to allow the computer to do as much as possible, but also allow users to focus their effort on those citations which are problematic or otherwise require human judgement. As the overall quality of the software improves, including additional citation indexes and improved parsers, the amount of human work required will decrease accordingly.

A Common Metadata Format

In order to aggregate the results of each citation parser, we had to choose a metadata schema for representing the elements of a citation. This schema had to contain all of the elements in a citation of the genres supported by L8X: journal article, conference proceeding, book, and cited website. In addition, the schema had to be extensible enough to include possible item identifiers, such as ISBN, DOI, or PubMed ID (PMID). The simplest schema to meet these requirements was a metadata format based on the OpenURL 1.0 scholarly formats (journal, book, dissertation) [15] in KEV (Key/Encoded-Value) encoding [16].

The choice to use OpenURL 1.0 was reinforced by the fact that two of the citation-parsing methods initially chosen for L8X were based on the OpenURL metadata elements. As a result, it was simplest to write a crosswalk from the parsers that returned non-OpenURL elements, and allow OpenURL-compliant parsers to pass data through directly. Table 1 shows a list of the parsing systems incorporated into L8X, and the metadata schemas used by each.

| Parser | Language/Procotol | Schema |

|---|---|---|

| Freecite | POST XML | custom |

| Lemon8-XML | PHP / regular expression | OpenURL 1.0 |

| Paracite | Perl | OpenURL 0.1 |

| Parscit | POST XML | OpenURL 1.0 |

Table 1. Citation parsing services/algorithms.

One of the main considerations for representing citations in the OpenURL schema and developing crosswalks was choosing elements for each genre of citation. This played an important part in the development of the citation editor UI, as well as the way in which scoring and comparison are done by L8X. The OpenURL 0.1 standard identifies journal, book, and conference proceeding citations as individual genres using the same metadata profile. However, the OpenURL 1.0 standard considers book and journal citations as different genres with corresponding metadata profiles, and conference proceedings as a variant of a journal article citation [17]. The mapped metadata profiles used in L8X can be seen in Table 2.

| Element | Journal Article | Book | Conference Proceedings | Web Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| authors | required | required | optional | required |

| atitle | required | optional | optional | required |

| title | required | required | required | optional |

| year | optional | |||

| volume | required | optional | ||

| issue | required | optional | ||

| edition | optional | |||

| editor | optional | optional | required | |

| chapter | optional | |||

| publoc | required | required | ||

| date | required | required | required | |

| sponsor | optional | optional | optional | |

| artnum | optional | optional | ||

| publisher | required | required | ||

| spage | optional | optional | optional | |

| epage | optional | optional | optional | |

| isbn | optional | |||

| pmid | optional | |||

| doi | optional | optional | optional | |

| targetURL | optional | required | ||

| access-date | required | |||

| comment | optional | optional | optional | optional |

Table 2. Citation metadata schema (elements in italics are mapped to OpenURL 1.0).

The original citation string is passed to each parser in turn: the results are serialised to XML, passed through an XSLT stylesheet mapping them to the L8X OpenURL schema (where superfluous elements are discarded), an accuracy score calculated, and added to an array of results. Rudimentary de-duplication and data cleaning is then performed. For example, ensuring the “year” only consists of a four-digit value, and the results are presented in the UI as an editable drop-down list. Very often, some parser plugins will produce highly inaccurate results, and although these are easily ignored by a human editor, additional data cleaning/checking could reduce this issue.

Overall, however, each parser will extract most of the citation correctly, and the combined results usually average toward an accurately-parsed citation, reflected in an overall parse score. The editor can then make any corrections they see fit – often, simply selecting the correct value for elements with multiple parsed results – and save the values to the database.

Aggregating Web Service Results

As in the parsing stage, results from online index databases are serialised to XML, passed through an XSLT stylesheet mapping them to the L8X OpenURL schema, and returned with an accuracy score as an array of results. However, obtaining structured citation information from online databases is more complex than parsing for a number of reasons.

To begin, each database has its own licensing restrictions, even “free” ones, and some require registration to obtain an API key for access to their data. At present, many large databases with a web service API provide some level of free access. For example, WorldCat provides access to registered (and thus, paying) OCLC members who request an API key for limited use. OCLC does, however, provide a limited set of free services with its xISBN offering. Generally, users must agree to terms of service which mandate non-commercial use of the data and limit the number of requests made on a daily or monthly basis [18].

In addition, obtaining citation information is itself a two-stage process: querying the database, and retrieving a structured record. Each database uses its own search interface and syntax, and the accuracy of the search is directly affected by the accuracy of the parsed citation, as well as the manner in which the search query is constructed. Moreover, the challenge in developing a search query lies in attempting to match a single record, not a list of possible results. When necessary, the L8X lookup plugins order results by relevance, and take the first (i.e., most relevant) in the list.

The request mechanism and result schema for searching and retrieving records differ for each online database. Most index APIs use a RESTful URI query syntax, but some require OAI HTTP POST or JSON. Similarly, most return results in a standardised XML schema (e.g., MARCXML, OAI-DC), but some use a custom schema or non-XML syntax like JSON. This means that each lookup plugin must contain the necessary metadata crosswalk to map results into the L8X OpenURL schema. Table 3 provides a list of the online databases currently supported by L8X, as well as a list of proposed plugins for development in the near future.

| Service | Scheme | License | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| CrossRef | OpenURL | free | journal articles |

| ISBNdb | URL | free registration | books |

| PubMed (MEDLINE) | URL | free | journal articles, conference proceedings |

| WorldCat API | URL | OCLC members only | books, journal articles |

| WorldCat xISBN | URL | free | books |

| CiteSeer | OAI | free | journal articles, conference proceedings |

| OAIster | OpenURL | free | journal articles, misc |

| LibraryThing | URL, JSON | free registration | books |

| OpenLibrary | JSON | free | books |

| Google Books | URL | free | books |

| Amazon | URL | free registration | books, misc |

Table 3. Web-based metadata index API services (items in italics are in development).

When a result is obtained from an online database, it is compared to the stored (parsed) citation by individual element and overall content, and a similarity score assigned. This score is intended to identify whether the record retrieved actually matches the citation, and whether any additional information (e.g., a URL, DOI, or full list of author forenames) was returned as well. Like the parser results, rudimentary data cleaning is performed, and the results displayed in the UI as an editable drop-down list. This allows the user to use the same interface for both parsing and searching.

An additional consideration with obtaining citation metadata lies in correctly identifying the genre of the citation at the parser stage. Since database content is generally genre-specific, the genre must be correctly identified in order to query the appropriate databases. As well, because content coverage depends on the parser plugins available, results will be improved over time as more online services are made available and plugins are developed.

Threshold-based Scoring System

Both citation parsing and lookup functions generate an accuracy score for each plugin —- methods differs between parsing and lookup, but both have been developed to return a percentage value between 0 and 100—which generally falls between 50 and 90 for relatively well-formed citations. The intent is not to present an absolute measure of the quality of the citation, but rather a relative indication of how well the parser or lookup service was able to generate a useful result.

Parser scores are calculated based on the number of metadata elements successfully extracted from a citation compared to the number of expected elements (e.g., 6 of 8 for a book citation would score 75). Lookup scores are calculated based on the percentage difference in content between the parsed citation and the result from the online index (e.g., a citation containing 100 characters that returns a result with 120 characters would score 20). This score is added to the aggregate parse score to indicate whether it is improved or not (e.g., 75 + 20 = 95, indicating that the lookup improved the citation’s data).

Scores are aggregated across all plugins and an aggregate score is calculated based on the value between the mean and maximum scores (i.e., maximum-weighted mean score). This reflects the fact that only one “good” result is required to be useful, while multiple partial results are more likely to improve the overall result than not. Empirically, scores from 50-70 tend to be good, 70-90 tend to be very good, and above 90 are excellent, essentially “perfect”.

This general ranking allows L8X to introduce the concept of thresholds into the parsing process to improve automation. By setting a minimum value for parse and lookup scores, the user can set a threshold for what they consider to be acceptable automatic parsing and correction: for example, deciding all parsed citations with a score above 60 to not require human editing and deciding all citations with a returned lookup score above 80 to have been correctly identified in the online databases. Using this threshold system means that L8X can automatically process the majority of the citations, and flag those that do not meet the thresholds for the editor to inspect manually via the UI.

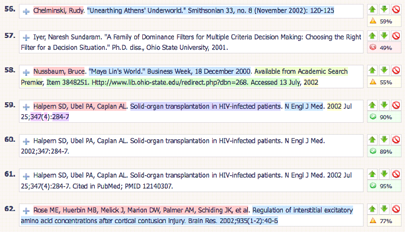

Citation Editing Interface

Another way in which L8X provides feedback to the editor about the accuracy of its parsing and lookup functions is to visually mark the elements of the citation that it was able to extract into individual metadata elements. Figure 2 shows an example of a citation (#59) that was successfully parsed into 7 elements (identified by coloured highlighting), with a score of 90 (in this case, the 90 comes from a successful lookup as well). By presenting information this way, and using simple iconography (i.e., a check-mark or red X icon), editors can see at a glance which citations require their attention, and where the problems most likely are.

Figure 2. Citation editor showing reference list and colour-marked parsed citation. [View full-size image]

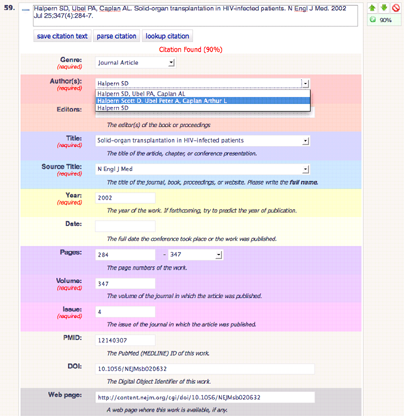

When the editor does decide to edit a citation, he clicks on an icon next to the marked contents, and the interface expands to display a list of the metadata elements and their values, as well as buttons for re-parsing or re-searching the citation metadata. When results are returned, they are displayed in this same interface; the combo boxes next to each element are populated with the results of the parse or lookup. A flashing asterisk appears next to any values that have been modified to visually draw the editor’s attention (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Citation editor showing expanded elements and combo boxes with online lookup results. [View full-size image]

Several other visual elements are also used to assist the editor: the background colours of each element match those in the marked citation and are grouped chromatically, editable combo boxes are used to allow the editor to simply select from a drop-down or make textual corrections (or both), and, the aggregate score is immediately displayed to let the editor determine the quality of the result.

The current user interface is the result of rapid user feedback during the development process, and contributes significantly to the effectiveness of the citation editing component of L8X. At the same time, there are still known deficiencies that are yet to be addressed. As a work-in-progress, it presents both an example of a successful user-driven interface as well as an opportunity for great refinement.

Future Directions

As Lemon8-XML is intended to be much more than a citation editor, there are several other areas of active development beyond those mentioned here. The goal of L8X remains to provide a tool for developing structure in scholarly articles, and many of the principles learned so far have application in other areas. For example, validating quotations against their canonical records in online databases, verifying author or cited speaker names against online name authority indexes, or even degrees of plagiarism detection and warning.

For citation editing, however, the main focus continues to be the addition of more online index services, particularly multilingual and non-English databases to improve the international applicability of L8X. In particular, there is great potential for a generic OAI or OpenURL-based lookup plugin, to allow institutions and publishers to access metadata in their own knowledge bases and union catalogues. Adding more support for additional citation styles—again, that are often non-English or specific to smaller disciplines, is another area for development. Finally, as part of the plan for developing integration between L8X and OJS, it may be desirable to provide the citation editing framework as a stand-alone service that can be installed or otherwise used independently.

The most obvious area for improvement remains the user interface for the citation editor. More visual indicators of the software’s progress and function are desirable, as is the ability for the user to configure the parser and lookup plugins’ function more specifically. For example, different thresholds for each plugin; re-ordering or disabling plugins on a per-article, per-citation, or dynamic basis; and dynamic feedback on each plugin’s results and score.

One area that holds particular promise is the ability to cite a resource by identifier alone; for example, using a PMID, ISBN, or DOI to uniquely identify a citation. Since L8X can resolve these to a full set of citation metadata, it is not inconceivable to imagine an entire reference list composed entirely of identifiers provided by the author. This itself raises another possibility: integration of embedded citation formats such as those provided by the Zotero OpenOffice plugin [19] to obviate the need for parsing altogether.

Conclusion

During the time Lemon8-XML has been developed, a number of reference management applications, including eXtyles and BibSonomy, have begun to incorporate limited parsing and lookup methods [20,21]. However, these tend to be limited to some combination of PubMed or CrossRef, far short of the roster intended by L8X. It is clear that this approach has great potential, and will only gain wider appeal as parsing algorithms improve and more databases become accessible. Improvements to the threshold scoring system will bring the software incrementally closer to fully automated citation correction, although it is probably naïve to think that it will ever remove the need for a human review.

As open source software, Lemon8-XML is freely available to download for anyone wishing to use it, as well as to those interested in collaborating on its development. The Public Knowledge Project maintains documentation and support for L8X [22], as well as a publicly-accessible demonstration instance at: http://www.lemon8.org. We would be happy to receive feedback from anyone interested in testing or developing L8X, either for their own purposes, or in collaboration with PKP.

Resources

[1] Thomson Researchsoft: EndNote, ProCite, Reference Manager, RefViz. http://scientific.thomsonreuters.com/info/rs_purchase_direct/

[2] Zotero browser toolbar. http://www.zotero.org/

[3] RefWorks. http://www.refworks.com/

[4] PubMed Central Overview. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/about/intro.html

[5] Inera aids Production Editors With eXtyles. http://www.inera.com/Seybold.pdf

[6] CrossRef Publisher Fees. http://www.crossref.org/02publishers/20pub_fees.html

[7] Open Journal Systems. http://pkp.sfu.ca/ojs

[8] No budget, no worries: Free and open source publishing software in biomedical publishing. http://www.openmedicine.ca/article/viewArticle/276

[9] ParaCite ParaTools. http://paracite.eprints.org/developers/

[10] FreeCite citation parser. http://freecite.library.brown.edu/

[11] ParsCit: An open-source CRF Reference String Parsing Package. http://wing.comp.nus.edu.sg/parsCit/

[12] OAIsterunion catalog of digital resources. http://www.oaister.org/

[13] CiteSeer.IST Scientific Literature Digital Library. http://citeseer.ist.psu.edu/

[14] ISBNdb.com. free ISBN database. http://isbndb.com/

[15] Registry for the OpenURL framework. http://alcme.oclc.org/openurl/servlet/OAIHandler?verb=ListRecords&metadataPrefix=oai_dc&set=Core:Metadata+Formats

[16] The Key/Encoded Value (KEV) Format Implementation Guidelines. http://library.caltech.edu/openurl/StandardDocuments/KEV_Guidelines-20041209.pdf

[17] OpenURL Syntax Description. http://www.exlibrisgroup.com/?catid={2F09A3E3-A22B-4CB1-8434-930CDB7264A7}

[18] xISBN Web Service http://www.worldcat.org/affiliate/webservices/xisbn/app.jsp

[19] Zotero OpenOffice Integration. http://www.zotero.org/support/openoffice_integration

[20] What’s New in eXtyles? Automatic Reference Correction. http://www.inera.com/refcorrection.shtml

[21] BibSonomy Scraperinfo. http://www.bibsonomy.org/scraperinfo

[22] Lemon8-XML. http://pkp.sfu.ca/lemon8

About the Author

MJ Suhonos is a system developer and librarian with the Public Knowledge Project at Simon Fraser University. He has served as technical editor for a number of Open Access journals, helping them to improve their efficiency and sustainability. More recently, he leads development of PKP’s Lemon8-XML software, as part of their efforts to decrease the cost and effort of electronic publishing, while improving the quality and reach of scholarly communication.

zayed, 2011-11-12

sir please tell me the parser setting required for lemon8 xml

openoffice is an essential for proper visuallisation of document