By Ryan Litsey & Scott Luker

Introduction

Interlibrary loan, or resource sharing, has emerged in the past decade to become one of the premier academic library processes. There are numerous articles discussing the potential for resource sharing to supplement the activities of the research library. However, along with the increase in usage, comes the increase in cost. This is illustrated by the literature surrounding resource sharing. While these articles are helpful for those looking to improve their resource sharing services, very few of them examine one of the core functions of a resource sharing unit, that being the shipping of books from the home library to the borrowing library. The reason this is not addressed in detail is twofold. First, much of the cost analysis consists of factors that are directly controlled and analyzed by the researcher. These costs are usually staff, equipment or resource related. Second, most of the interlibrary loan systems that libraries use to process and manage requests do not track or analyze the library shipping. Libraries have compensated for this by using vendor provided solutions like UPS World Ship. The challenge with these options is that they only provide data concerning shipping with that particular vendor. The OBILLSK Shipment Tracking system allows a consolidated picture of all ILL shipping across any platform. It also provides the library with new functionality that helps them to understand the whole picture for shipping. Resource sharing is all about collaboration and cooperation; through the OBILLSK Shipment Tracking system, libraries can experience a new level of integration that has not been seen before. Before getting into the discussion of how and what the system does, it is important to look at some of the arguments that other practitioners have made concerning cost and shipping.

Background

The shipping costs for interlibrary loan and the cost for the operations of the unit in general cannot be separated. Even if the percentage of total physical items shipped is going down, shipping costs will remain one of the biggest expenses any library engaging in interlibrary loan. Tolppanen and Derr found that up to 38% of all borrowing requests at their library were considered loans or items that required shipping. [1] Such a large amount of shipping means libraries could benefit from investing more in monitoring shipments. The large numbers of shipping and the costs associated with shipping items, can serve as a potential barrier for libraries sharing items through ILL. This is for two reasons. First, libraries may not be willing to share items, especially costly ones, if they fear it will get lost in the mail. Second, libraries may also want to know more about a potential lost book before paying the invoice. Since lost books represent additional costs, libraries grow more and more hesitant to lend if the books get lost. Both examples are intrinsically linked to the issue of the cost of interlibrary loan operations. This hidden sunk cost is very rarely recognized in the literature. It is a sunk cost because libraries pay these shipping costs and lost book fees with very little analysis of the logistics of what is happening with shipping and lost books. Naylor, in the article “The Cost of Interlibrary Loan Services in a Medium-Sized Academic Library,” develops a very effective formula for determining cost of interlibrary loan operations. [2] However, since their formula does not account for shipping costs it is incomplete. Leon and Kress also undertake a cost assessment of interlibrary loan activities. [3] Their research showed that up to 19% of the cost of interlibrary loan is for shipping physical items. The article concludes with a call for a more granular accounting of borrowing costs. However, without the ability to perform sophisticated shipping analysis for libraries, the authors are hard pressed to conduct such an analysis.

As libraries invest more money into in-depth physical collections of audio and visual materials, being able to track these materials will become a cost saving imperative. This is especially true for academic libraries and collections like the Criterion Collection. Being able to track these costs is another advantage that a robust shipment tracking system provides. Tracking items will give libraries added assurance and increase the lending of audiovisual items. Beaubien et al. in their article indicate an increase over a three-year period in requests for audio and visual items.[4] The article concludes with a call for increased lending of these items which will place a greater emphasis on being able to track these often expensive and unique resources.

Aside from the cost-savings accurate tracking can provide, there are additional points of interest for a comprehensive tracking system. The packaging of items by both the requesting library and the lending library is not always the most effective containment, meaning packages break open and items get lost in transit. This represents another liability for the library. If items are lost and there is no clear way of identifying the package or the contents, then recouping those costs can be difficult. This notion is echoed by Baich et. al in their article discussing the most recent revisions to the American Library Association Interlibrary Loan Code of the United States.[5] As part of a discussion about the revisions, they identify some trends that came from a survey conducted during the code’s revision process. They write, “Several themes emerged around the proper handling and processing of materials. First, there were a variety of comments suggesting a stronger emphasis on proper and secure packaging of materials to prevent loss or damage.” [5] Additionally, given the lack of information concerning the shipping process it is difficult to identify bottlenecks or look for areas of improvement. Sanchez, in a book about interlibrary loan benchmarks, gave a physical loan benchmark turnaround time of 7.67 days. [6] Regardless of whether or not a particular library thinks that is fast or slow, without more detailed information about couriers and supply times, it is difficult to analyze that data in greater detail. OBILLSK Shipment Tracking offers libraries data points they have never had before.

How it Works

The architecture of the shipment tracking web software consists of a variety of server-side and client-side technologies. The core source code is written in C#.NET, in conjunction with a SQL Server database. Client-side frameworks include Bootstrap and jQuery for responsive design and data validation, Shield UI for data visualizations, and jVectorMap for geographical representation of shipments. Python programming and JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) text file formatting are used to facilitate the efficient creation and delivery of maps. Visual Studio, an integrated development environment (IDE), is the primary tool used to create and maintain the web software. The main components of the software are the scanning and tracking web forms. The simple design facilitates ease of use by all personnel.

Scanning

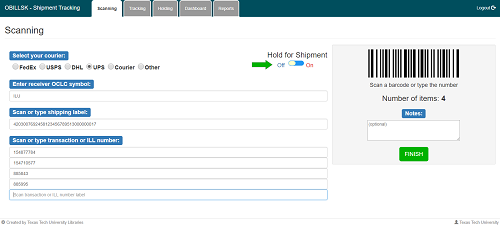

The scanning form consists of a series of text box inputs controlled with jQuery JavaScript libraries. Users may scan labels with a barcode scanner or type the information into the web form. To assist with multiple scans for a single package, timing delays and field auto-focus techniques are enforced. In other words, users are able scan a shipping label and all contents without having to use the mouse. The form is validated for field character lengths and warns the user when a shipping label was previously scanned. To give an example, a student worker accesses the main scanning form, and from there they are presented a radial button to select the courier type. Once that option has been selected, a new field appears where they select the OCLC symbol of the library where the item is going. This allows for geographical mapping, which will be discussed later. The next field that appears after the OCLC symbol field is the scan shipment label field. This represents one of the core functions of the system. The inputting of the label, in conjunction with the already selected courier, forms the backbone of the tracking system. After scanning of the shipping label, the student worker scans the ILL number for each item that is part of that shipment into the following fields (see Figure 1). There is no limit to the amount of ILL numbers that can be scanned. The most that have been scanned so far is 90. From there, the user is given the option to add notes if they wish. Finally, the user clicks “finish” and that moves the data to the shipping tables on the server. Below is a screenshot of a completed scanning form.

Tracking

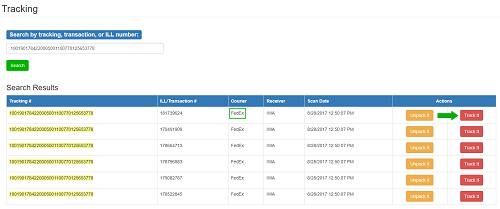

The tracking form provides a search box and displays all items associated with a specific shipping label. Users may enter an ILL transaction, item, or tracking number, which initiates a query of the database. The system performs an exact search and displays the results as seen below. We chose to not code for a wildcard search because the searchable items are primarily numeric and to increase search speed.

Extensive research with each major courier’s application programming interface (API) was required to accomplish the desired objectives of the software. The research assisted in the assessment and scope of industry standard tracking numbers and practices. The first development strategy was to integrate the courier APIs into the tracking software; however, many of the APIs developed required legacy versions of the .NET framework. For this reason, the development team chose to link to the respective courier’s tracking webpage, passing a tracking number in the URL query string, instead of integrating the courier APIs with the software.

The search results display in an HTML table and include pertinent information such as courier, receiver, scan time, unpack and track. “Unpack It” is a clickable button that triggers a dialogue box (Bootstrap modal) which contains all items that were scanned and contained in the package. This information is also exportable as a text file to the user’s local device. “Track It” is a second clickable button that opens a new browser tab and links to the courier’s tracking web page specific to the tracking number. Again, linking to the courier’s website was deemed the most logical long-term practice. The form, which can be seen below, was designed to be as simple and easy to use as possible. The user is provided with a single box for data input and is offered a series of choices stemming from the data that is used. The reasoning behind keeping the box simple was the belief that the page will be used when searching for lost items. Searching for lost items often begins with one of two pieces of information: the ILL number or the shipping label. Thus, those are the only search options currently on the form.

Data Visualization

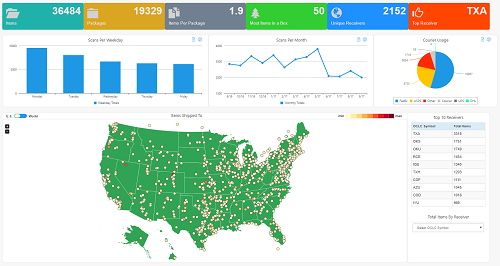

Another main objective of the software is to incorporate modern data visualization design and provide a snapshot, or dashboard, of scanned item metrics and geolocations. The software uses a licensed third-party JavaScript/HTML5 framework called ShieldUI to generate interactive graphs and charts. This framework offers ASP.NET server-side wrappers for a variety of JavaScript controls. The data is dynamic, meaning that the queries are executed each time the page loads providing real-time statistical information. Using ShieldUI enabled the programmers to spend more time focused on data structures, analysis and query development.

The most challenging and rewarding aspect of the software was dealing with the visual representation of geolocations specific to shipments for each institution. The final solution consists of multiple components – a database table containing longitude and latitude coordinates, a script to generate text files, and a client framework to render maps on a webpage. This model lessens the workload on the web application by reading from a precompiled text file containing necessary data for the map to read, as opposed to executing queries and compiling the data for the map to read on every page load. A Python script, external to the web application, is periodically executed and queries each institution, loops through each shipment receiver, obtains coordinates and writes a JSON text file for each institution.

Example text file:

{ "all": {

"names":

["Location 1 Name", "Location 2 Name"],

"coords":

[[40.7294385, -73.9994011], [40.7286908, -73.9978484]],

"item_count":

[1360, 6],

"oclc_map":

["Location 1 OCLC Symbol", "Location 2 OCLC Symbol"]

}

}

Each text file contains names, coordinates, counts and OCLC symbols for each shipment destination. The United States and world maps, based on jVectorMap, are rendered by reading the associated text file.

The final challenge of the web software deals with time zone differences. All timestamps on webpages and exportable reports should coincide with the scanning location. The initial strategy was to write custom code to determine UTC offsets for each user. This plan was deemed unmanageable early in the project due to daylight savings time, international locations, and manual upkeep. The solution was to use TimeZoneInfo, a built-in C# class. This class can convert time to another time zone based on the time zone of the web server and accounts for daylight savings time. The database contains a table populated with all time zone names and UTC offsets. Users have the option of selecting a default time zone for their account. The web application queries the user’s time zone selection and applies the TimeZoneInfo class described above and all timestamps are reflected appropriately.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The OBILLSK Shipment Tracking system is one of a kind. It is able to solve many of the more traditional issues with shipping and interlibrary loan, but is also holds near limitless potential for integration and interaction between libraries that was previously not possible given existing shipment tracking systems. As we have seen above, the OBILLSK system provides libraries with consolidated shipment information. Data that can be provided by the system ranges from real time tracking information to geo-located shipment patterns and custom date range reporting to shipment notification emails. All of these processes work to help interlibrary loan units accurately assess and track their shipments; giving libraries a more complete data picture for the shipment processes that happen potentially thousands of times a year. With access to new data comes new opportunities.

Some of the future opportunities for this system are practical while others offer a glimpse at resource sharing of the future. In the next year or so, we are looking into adding a receiving element to the process. Adding receiving will give libraries the opportunity to identify items lost in transit at the moment of receipt, in the hopes of identifying potential problems early in the process when a solution may be more readily found. Also, with adding in receiving the system will, for the first time in resource sharing, be able to identify library by library shipment times. When the patrons ask, “Where is my book?” the library will no longer have to give an estimate for when the book will arrive. They will now know down to the minute the amount of time it takes to get an item from university “a” to point “b”. From this, we can envision a new type of resource sharing. If the system is tracking all of the physical loans that move from library to library, then it is possible to analyze the data more completely. It will make it possible to see whether certain subjects or topics are being utilized at “x” university or being supplied by “y” university. While there are existing internal ILL systems track this type of data on an individual request level. There was no way to see this behavior between libraries until OBILLSK. This creates a situation where collections within a consortium could potentially move between groups of libraries to meet the evolving needs of patrons. This is just a snippet of the potential for the OBILLSK Shipment Tracking system and the data that it collects to not only solve current problems, but open opportunities for the evolution of resource sharing to meet the needs of the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable help of the members of our shipment tracking Advisory Council; Baylor University, Lehigh University, New York University, Michigan State University, University of Houston, University of Kentucky, University of South Carolina, West Virginia University, John Berger from ASERL, Bea Rodriguez from AMIGOS, Cathy Wilt and Jill Morris from PALCI.

About the Authors

Ryan Litsey (Ryan.Litsey@ttu.edu) is the Associate Librarian and head of Document Delivery at Texas Tech University. A graduate of Florida State University with a degree in Library and Information Sciences, he has spent a majority of his academic career developing ground breaking technologies that have endeavored to transform Resource Sharing. Both Occams Reader and the shipment tracking system OBILLSK have changed the way ILL librarians are able to share the resources of their respective institutions. Ryan was recognized by the Library Journal as a 2016 Mover and Shaker in library technology. His first book Resources Anytime, Anywhere; How Interlibrary Loan Becomes Resource Sharing address how libraries can rethink the traditional notions of interlibrary loan and come to understand resource sharing. He is also active in several ALA – RUSA/STARS committees, he is a consulting editor for the Journal of Access Services, the Journal of Academic Librarianship and the associate editor for the Journal of Interlibrary Loan Document Delivery and Electronic Reserve. His academic research is in resource sharing, machine learning, predictive analytics and anticipatory commerce.

Scott Luker (Scott.Luker@ttu.edu) is a Programmer/Analyst at Texas Tech University Libraries. He has developed software and web applications for document delivery, circulation, and digital collections. In addition to programming, he has professional experience in server and database administration, learning management systems, and media production. Scott is proficient in PHP, ASP.NET, C#, Python, SQL Server and MySQL. His current interests include augmented reality, “big data” projects, and media-based solutions. Scott earned a Bachelor of Arts from Texas Tech University.

References

[1] Tolppanen, B. P., & Derr, J. (2010). Interlibrary loan patron use patterns: an examination of borrowing requests at a midsized academic library. Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery & Electronic Reserve, 20(5), 303-317.

[2] Naylor, T. E. (1997). The cost of interlibrary loan services in a medium-sized academic library. Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery & Information Supply, 8(2), 51-61.

[3] Leon, L., & Kress, N. (2012). Looking at resource sharing costs. Interlending & Document Supply, 40(2), 81-87.

[4] Beaubien, A. K., Kuehn, J., Smolow, B., & Ward, S. M. (2006). Challenges facing high-volume interlibrary loan operations: Baseline data and trends in the CIC Consortium. College & Research Libraries, 67(1), 63-84.

[5] Baich, T., Dethloff, N., & Miller, B. (2015). Unlocking the Interlibrary Loan Code for the United States. Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery & Electronic Reserve, 25(3-5), 75-88.

[6] Sanchez, E. (2009). Higher education interlibrary loan management benchmarks. Primary Research Group Inc.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply