By Rebecca Townsend and Camille Mathieu

Introduction

For any organization with significant digital content, the ability to search across this content has become an operational necessity. Despite this, unified enterprise search and retrieval of digital content remains an elusive goal for many organizations (Miles, 2014). The large amount of time that knowledge workers spend trying to find relevant information when they need it, in addition to the time they spend re-creating information when it cannot be found, represents a significant cost to any knowledge-producing organization (Feldman and Sherman, 2001).

In the two decades since this “high cost of information” was uncovered, many commercial enterprise content management solutions and consulting agencies have cropped up which strive to diminish this cost. One approach in solving findability issues is to rely on technology investment and the implementation of artificial intelligence, machine learning, natural language processing, and similar cutting-edge tools (Findwise, 2016; Miles, 2014). Additional and very different solutions crop up when the focus shifts to enterprise content itself. Rather than focusing efforts and investments on new technologies, it is possible and potentially more valuable to address issues of findability and aggregability at the source, from the moment knowledge is captured in an enterprise information ecosystem.

One such enterprise information ecosystem underlies the daily operations of the NASA/Caltech Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, CA. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) – a world leader in robotic deep space planetary missions, Earth monitoring systems, and associated science and technology – has an intranet with digital content housed in over 100 different repositories, applications, and other storage locations. The storage locations contain documents and other items in a variety of formats, created by thousands of different knowledge workers (employees whose daily work products rely on interactions with enterprise information) over the course of the ecosystem’s life. While some of this information is structured, the majority is unstructured. Because of this proliferation of repositories, as well as the inconsistent description of content within them, critical information is frequently siloed and difficult to access. As a result, it has been challenging for JPL to implement findability tools which can effectively search across siloes or manage content in a unified way.

While JPL has invested in a number of technology solutions designed to allow for better content findability, the software approach has not been the only approach taken by the institution in addressing this challenge. JPL is a matrix organization; one of the results of this structure is that, historically, formal knowledge management has been mandated for some work (i.e. flight projects), while significantly less knowledge management has been mandated for information produced as a result of daily business operations. This paper will review some of the work JPL has recently engaged in to fill this gap and better maintain the knowledge it produces. Specifically, it will review a recent “knowledge curator” pilot role, and the projects and outcomes of this role pilot. This paper will argue that, regardless of the specific content management system (CMS) used by an organization, effective enterprise content findability requires some manual review and editing in order to produce results that meet users’ expectations. Additionally, it will make the case for an expansion of traditional library and information science (LIS) roles to include tasks associated with “knowledge curation,” specifically for enterprise intranets and other finite information ecosystems.

Findability and the Enterprise

Studies conducted since the establishment of the high cost of information in 2001 have consistently found that information findability remains a central issue for many knowledge workers and their employers. An industry study from 2013 found, for example, that “60% of information workers say it is difficult to find the right information,” and that, by spending “an average of 8.8 hours every week searching for information,” workers were costing their organizations “$14,000 per employee each year” in lost productivity (Leher, 2013). Another study, conducted three years later, found that “around 45% of respondents” said that “they are dissatisfied with the enterprise search applications,” while a third of respondents say it is difficult to find information in their organization in general (Findwise, 2016). This continuing dissatisfaction has many root causes, one of the biggest drivers of this ongoing issue is the fact that user expectations are increasing rapidly. Search and information retrieval tools outside of the enterprise are growing ever more sophisticated, while internally, the same tools seem cumbersome and inefficient. One of the biggest drivers of dissatisfaction with enterprise content findability is the consistently excellent experience of findability that users experience outside of the enterprise.

While significant cost associated with poor content findability has been well-established, there are also large costs incurred in implementing solutions to this content findability issue. One paper addressing this issue notes that, despite the “substantial” benefits associated with descriptive business metadata, such individual solutions can also have “an inherent saliency problem” such that “the cost associated with the time it takes to pre-categorize documents… is a major perceptual impediment to the implementation of a navigable document hierarchy” (Schmyik et al., 2015). Though it may be hard to prove a return on investment given the “soft costs” (Athey, 2009) of knowledge worker time and reuse benefit, there is certainly a financial incentive over time for organizations that address findability issues at the root of the problem, rather than via technology applications later down the line (Wu et al., 2009).

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory has likewise been considering the question of more effective knowledge management since the early 2000s. One document written during that time addresses some possible strategies for encouraging knowledge capture within the organization, such as “Recognize and reward people for sharing knowledge,” “Encourage and support communities of practice,” and “Strike a balance between long-term corporate needs (capturing knowledge) with short-term local needs (completing a task quickly)” (Holm, 2001). All of these strategies implicitly assume the support of the institution for knowledge management practices, and the significant benefits that result from strategically intervening in employee knowledge capture processes. A later revival of these efforts lead to the determination of similar best practices which currently inform JPL knowledge curation, namely: “historical technical records of JPL work should be available to all relevant employees who meet ITAR requirements,” “metadata for search purposes can be easily added,” and “refining access groups and authorizing access are straightforward processes” (Devereuax et al, 2015).

In a 2018 interview, JPL Deputy Chief Knowledge Officer Charles White advocates that enterprises take up the mantle of “knowledge husbandry,” since he foresees that the “next frontier” of enterprise knowledge management will not just be getting people to share their information with repositories, but getting repositories to share information with other repositories. “We haven’t been good at networking information systems,” says White, “and moving forward, we need to talk about a system of systems” (White, 2018). The future of findability in the enterprise relies on the ability to break down silos and provide a unified view of enterprise content.

The ‘Knowledge Curator’ Role

The pilot of a “knowledge curator” role emerged as the result of a collaborative partnership between two organizations at JPL: the Mechanical Systems Engineering, Fabrication, and Test Division (35x) and the JPL Beacon Library Group (319x). The JPL Library had long supported efforts by the 35x engineering division to capture and effectively store information, specifically using the institutional wiki. However, in order to scale up knowledge capture and organization efforts, a new, more formal role was required. Since it was clear to both parties that a library and information science (LIS) skill set would be ideal for implementing knowledge capture solutions, an MLIS student intern was hired within the 35x engineering division to do embedded LIS work for that division. This student intern was hired to work part-time for just over 6 months, from February 2018 to August 2018. The work performed by this student intern can be broken down into thematic projects as follows:

- Guided document creation, i.e. the development of wiki portals and standard editing processes for consistent knowledge capture

- Search curation, i.e. manual and organic enterprise search relevancy improvements

- Index as intervention, i.e. metadata mapping and information modeling to improve access to content for both local and enterprise-wide applications

These project tasks, as performed by the student intern, began to form the basis for a new role at JPL: the role of the “knowledge curator.” This new emergent role is characterized by an ability to perform tasks which are both manual in that they allow for rapid changes to increase content findability, and organic in that they allow for more long-term, systemic changes to that same end. Additionally, this role encourages proactive curation activities using implicit user feedback in search logs and other metrics, as well as the ability to be reactive to evolving user needs, expectations, and explicit feedback. The role of the knowledge curator is to intervene strategically at each stage in the knowledge management process, from creation and storage to search and retrieval for reuse. In action, this translates to facilitation of content creation and knowledge capture, improving the user experience of information storage and retrieval, and designing architectures that both make users’ jobs easier and align with institutional goals. Finally, this role uses traditional LIS skills in an innovative new challenge: understanding the dual function of the enterprise knowledge worker as both content consumer, and content creator. To develop this understanding, the knowledge curator role seeks to improve organizational information literacy and to foster a shared culture of knowledge capture.

Strategic Interventions

In order to support better knowledge management at JPL, the knowledge curator makes small, calculated adjustments to existing employee workflows and/or existing findability tools. These adjustments are designed to be as non-invasive as possible while at the same time having a discernible effect on the findability and usability of enterprise content. The current success of the solutions employed by knowledge curators is in part a result of the high-impact, low-cost design. The following three interventions were initiated by the knowledge curator intern during her half-year tenure.

1. Guided Document Creation

Figure 1. JPL Wired Logo and landing page.

The primary project for the knowledge curator was guided document creation within the context of JPL’s internal wikipedia, JPL Wired. Enterprise wikis are valuable knowledge management tools in use within many organizations (Seibert, 2010). JPL’s Wired wiki is built on the collaboration platform Confluence, and is open to everyone in the JPL community, with the notable exception of foreign nationals (JPL employees who are not US citizens, who make up less than 5% of the workforce.) JPL Wired began in 2009 as a way to help newly-employed engineers find content that was critical to their work. Over time, the Wired “intrapedia” spread beyond its initial audience and user group, as the wiki filled a niche knowledge management need by allowing any JPL employee to directly contribute to JPL’s collective knowledge (Rober and Cooper, 2011). In 2016, after several years of undirected growth, the Wired wiki got a boost when the Wired Steering Committee was initiated. The committee began to design tools for wiki content creators and users, such as indicators of page validity (Wiki Confidence Level indicators) and Wired portals (structured areas to support collaborative content creation from subject matter experts). The Wired Steering Committee then brought on the knowledge curation intern in early 2018 to further the adoption of Wired portals among various subject matter expert groups (or “communities of practice”) at JPL.

Wired portals are modeled on Wikipedia Portals and Wiki Projects, which are the landing pages for communities of editors. Each community of editors is focused on a specific topic or domain within Wikipedia. Wikipedia’s Portals and Projects help to create structure and consistency within the wiki site. Portals and Projects also help the communities of editors to assure that articles within their domain are systematically monitored for accuracy. In the same way, Portals in JPL’s Wired wiki were developed with the intention of establishing a functional information architecture and a community dedicated to the upkeep of content around a given area of expertise. This need to efficiently facilitate knowledge sharing within a community of practice arose because, due to the matrix structure of JPL as an institution, individual employees working on different projects previously did not have an easy mechanism for sharing knowledge, even when the nature of their work is similar. Wired Portals, created around JPL communities of practice, provide a centralized location for knowledge capture and sharing of lessons learned that circumvents the matrix structure and crosses project lines.

Figure 2. The landing page of the Wired wiki Portal for the Extraterrestrial Sampling community of practice at JPL.

The role of the knowledge curator in establishing Wired Portals was to assist these communities of practice by helping to identify categories of articles within that community’s scope. These “categories of articles” have typically followed two veins: 1) article type, and 2) article topic. That is, when allowed the opportunity to self-organize, subject matter experts tend to tangibly organize their tacit knowledge first by document type (i.e., “Training Resource,” “Reference Material,” or “Sample Product”) and then by subject (i.e., “Entry Stage,” “Parachute Descent,” “Landing Stage”). By sorting existing Wired content into categories such as these, communities are given an opportunity to identify gaps in content and suggest standard information required for new articles within a given category. After two or three meetings with a few key stakeholders within a community of practice, a larger group comes together for an “edit-a-thon” to begin labelling, editing, and creating new content. Wired edit-a-thon participants will typically add labels to content, and paste into each article “navigation boxes” and other standard information that provide links to related content and to the portal homepage. This inclusion of set labels and standardized information makes existing content more findable by providing multiple points of entry to articles.

In addition to providing technical support and information architecture set up for the Wired wiki portals, knowledge curators facilitate strategic thinking within the communities of practice by asking members to consider how future users of their articles might best find their content. Questions like “if you were new to JPL, what would you want to know about this topic?” and “what would you as a new hire expect to find in this type of article?” lead to additional structure recommendations for individual articles and the wiki portal as a whole, making the community’s content more findable and usable over the long term. This additional structure is not only valuable to the communities of practice experts as they fulfill their roles as content creators, but also helps to align their content with institutional priorities for content usability. The structure added to Wired portals and portal articles helps to inform enterprise-wide taxonomy and facilitates better integration with JPL’s internal intranet search.

2. Search Curation

“Successful enterprise search,” according to information architect Marianne Sweeny, “is not achieved through spontaneous assembly of features and programming” but rather through “a clear understanding of search behavior inside the fire wall so that the right search features will be mapped to specific needs and behaviors” (Sweeny, 2012). The aspect of “mapping” search to meet enterprise user needs is one of the functions of the knowledge curator role. The JPL Library, in conjunction with the knowledge curator intern, engages in targeted enterprise search improvement called “search curation.” JPL’s intranet has an internal unified search, known as JSearch, which is built on the open-source search engine Elasticsearch (as of this writing, Elasticsearch version 2.3.5 is in use). Up until 2014, JPL used a Google search appliance to run its unified search. However, the black box nature of the Google appliance, combined with higher expenses that made scaling the search impractical, drove the Lab’s Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO) and the JPL Search Team to evaluate alternatives. Elasticsearch was selected and has been in use since that time. JSearch currently indexes hundreds of internal intranet pages, and documents from cloud-based document stores. Though this is only a fraction of the repositories currently in use on Lab, the scope of the search index is constantly expanding.

Users of JSearch consistently rate the Elasticsearch systems as better than the Google appliance; however, the majority of searchers still experience poor results relevancy, especially for uncommon search queries. A lack of linkages between internal web pages, minimal metadata attached to sites, and varying levels of access for different employees all contribute to the challenges of effective organic enterprise search. While more automated solutions are developed behind the scenes, a manual fix is in place. Since 2014, the JPL Library and the OCIO have collaborated on the search curation project, using a software tool built in-house to perform targeted, manual adjustments to JSearch.

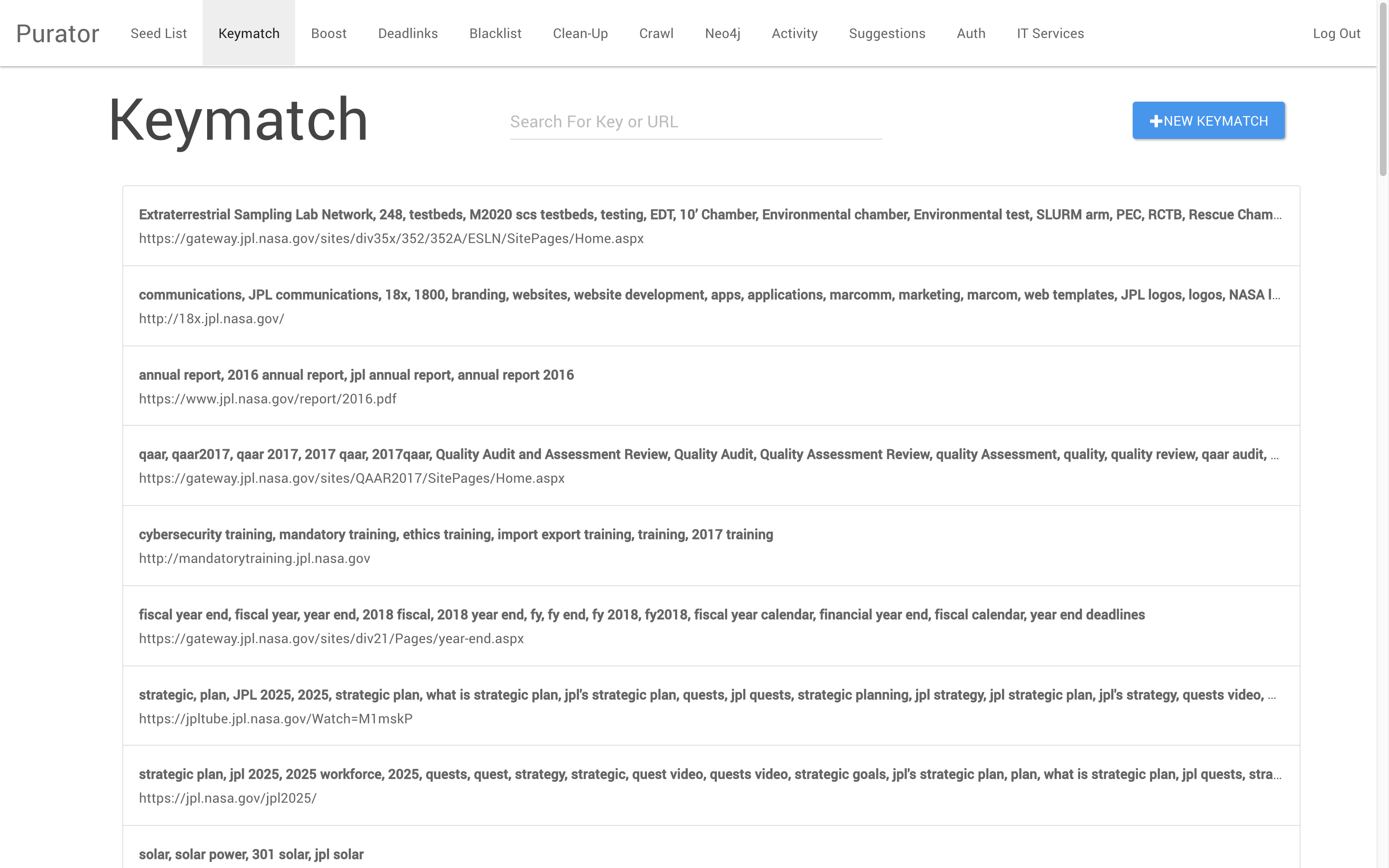

The Purator tool is an internally-developed tool which can be used to create search cards, map results to keyword queries, boost or downgrade organic search results, and index sites. The tool was developed by the JPL Search Team. Information managers use the Purator tool to make edits directly to the search index after edits are either 1) requested by knowledge workers who report that they cannot find what they are looking for, or 2) sourced from search logs and metrics. The Purator tool’s code repository is located in JPL’s Github Enterprise instance. While the code is considered proprietary and not cleared for inclusion in this paper, interested parties should contact the authors (library@jpl.caltech.edu) for more information and specifics on the Purator tool code. For search logs and metrics, Matomo (previously Piwik) is used. Matomo is an open-source web analytics application used to determine what JPL knowledge workers are searching for so that the appropriate results can be mapped to user needs. While there are a variety of functions enabled by the Purator tool, the most commonly used for search curation are Keymatch, Boost, Seed List, Manual Crawl, Clean-Up, Deadlinks, Blacklist, and Knowledge Cards.

Keymatch

The most often utilized tool of the Purator suite is Keymatch. This function allows curators to boost certain links whenever a series of associated keywords are queried in the search system. For example, the terms “calendar” or “fiscal year” may both retrieve as the top result a link to information about the fiscal year end if that information has been keymatched to those terms. This function is designed to be similar to what in search is sometimes called ‘best bets,’ or to sponsored search results in Google, which are featured at the top of search results and more prominently for certain keywords. A single keymatch record may have many different query terms associated with it, but each record may only point to a single resource. Typically, curators use the keymatch tool to boost certain known-items to the top of search results pages. These known items are frequently guidance, how-to, or reference documents and web pages, while boosted links to applications are typically developed using the knowledge card tool.

Figure 3. The Keymatch landing page, showing keymatch records.

Knowledge Card

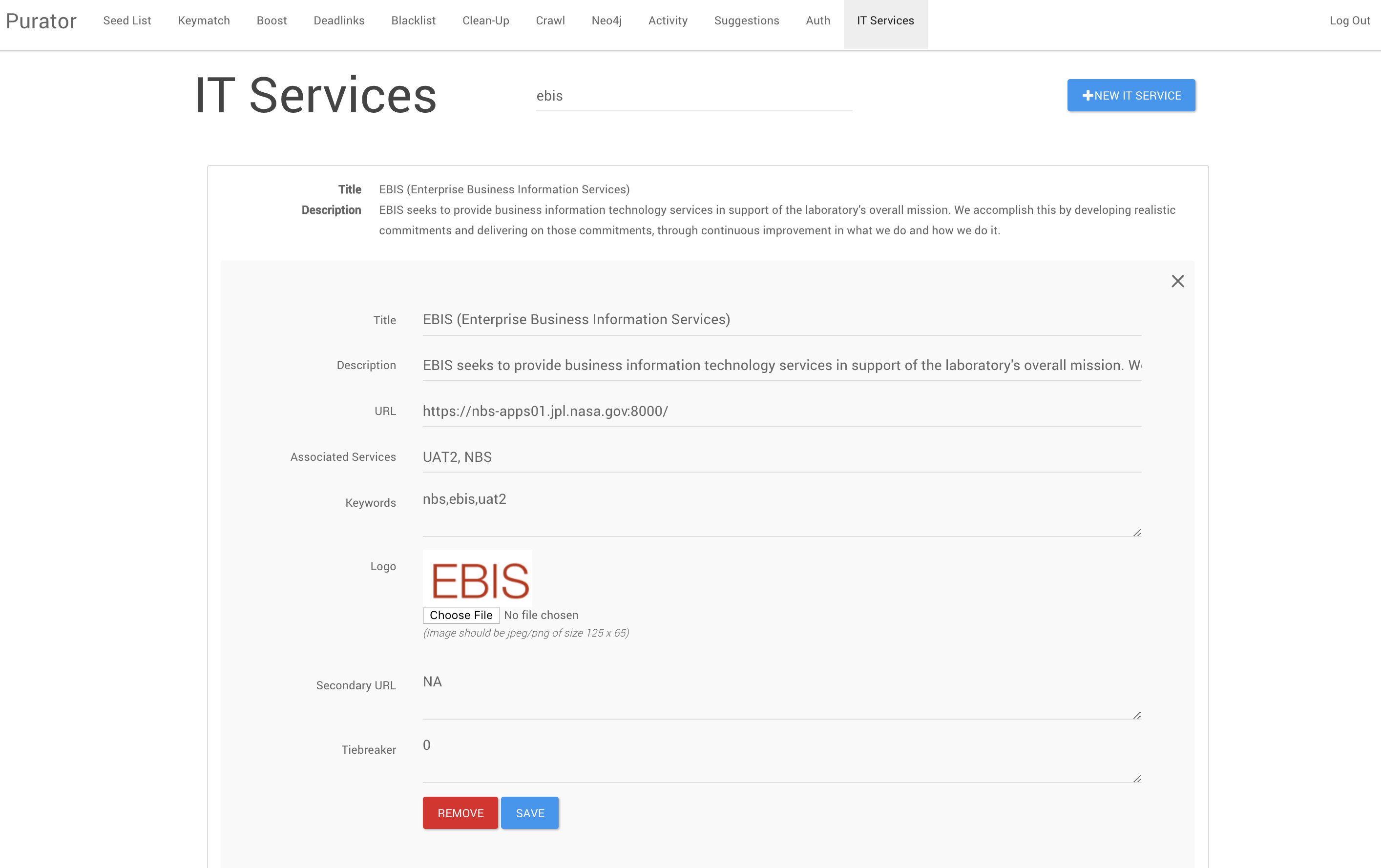

The Knowledge Card tool is the most unique in the Purator’s suite of tools. This tool was added in after all the others, in an update about two years after the Purator was first being used. It retains its original name, IT Services, as it was originally intended to be a card catalog of IT tools only. However, the usefulness of this tool impressed curators and patrons alike, and the IT Services tool quickly turned into a general Knowledge Card tool, used to describe any entities at JPL, not just IT tools and services. Future updates to the Purator tool will reflect this more general usage of the Knowledge Card function.

Knowledge cards are created manually by curators, and automatically appear at the top of search results pages for given queries. As alluded to, Knowledge Cards tend to be created for JPL “entities,” such as specific online resources, cafeterias and other service centers, missions and projects, or other named items on Lab. This focus on creating cards for entities comes from an attempt to mimic Google search results, which often include knowledge cards for entity searches. In addition to fields where the curator may specify the title, URL, and associated keywords for a knowledge card, curators also include logos for each of the cards, either sourcing one (via screenshot/download) from the resource being described or generating a logo as needed.

Figure 4. The Knowledge Card record for JPL’s EBIS tool, shown in edit mode.

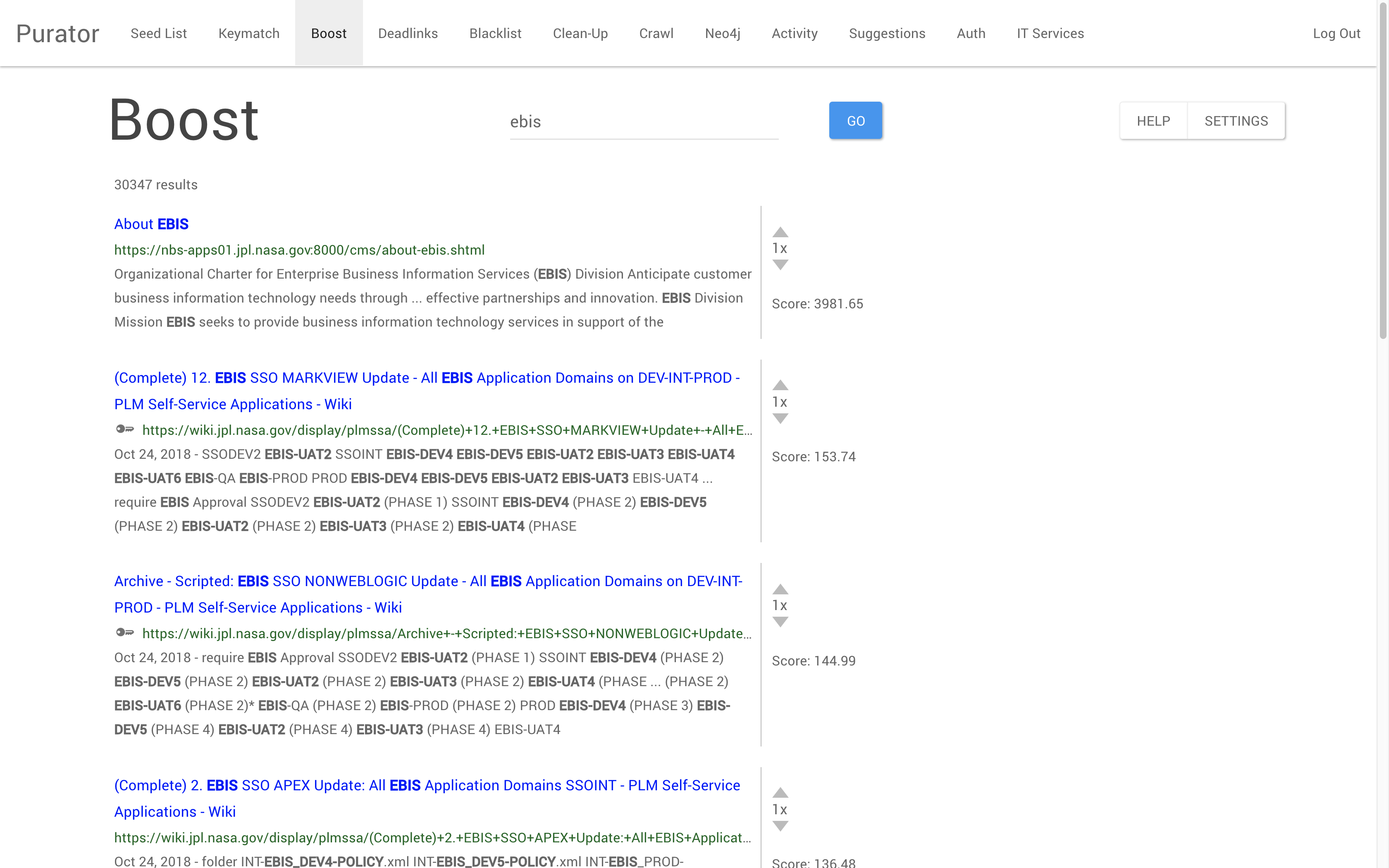

Boost

Similar to the Keymatch and Knowledge Card functions, the Boost function allows for the improvement of search results on a query by query basis. However, unlike these other tools, boosting can be considered a more organic form of search curation. Both Keymatch and Knowledge Card functions involved creating a distinct record, which is then inserted into the search results. Boosting, however, allows curators to directly increase or decrease the weight of a certain result in the search index. Weights are calculated for each search result retrieved by the system for a given query; the Boost function allows curators to tip the scales and artificially reorder the index weighting for certain query term searches.

Figure 5. The Boost function for query ‘ebis,’ showing a boosted result (‘About EBIS’) that has been heavily weighted in the search index.

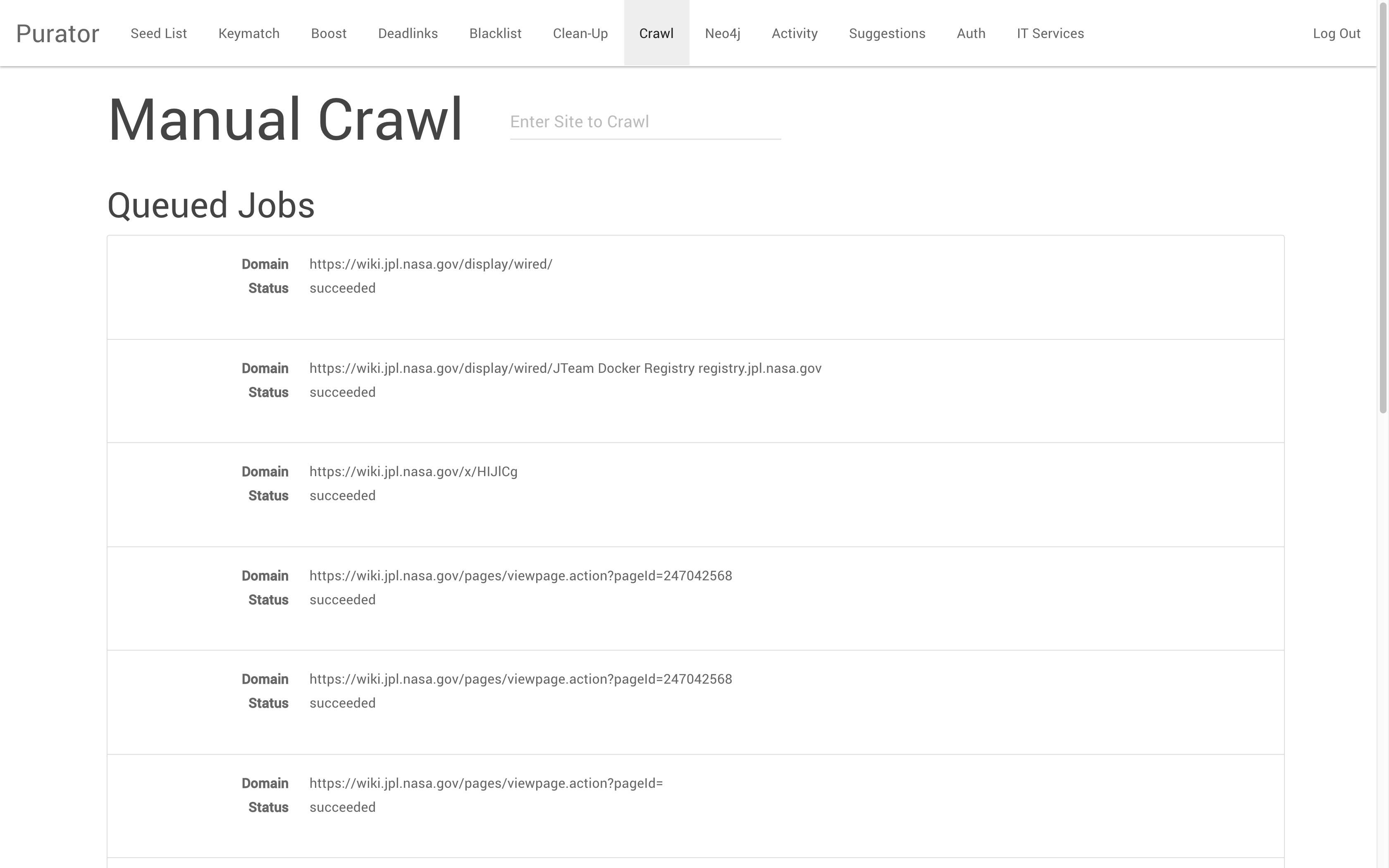

Manual Crawl and Seed List

JSearch’s search crawlers index contents from JPL’s intranet according to a seed list of sites to crawl. The Purator tool allows curators to edit the Seed List by adding or removing URLs which should or should not be indexed by search. This function is especially helpful when sites are commissioned or decommissioned. Typically, this function is used when a JPL employee creates a new internal web site, and want to ensure it is made available via the enterprise search system. Similar to the Seed List is the Manual Crawl function. This tool allows curators to push a one-time, “manual” crawl of a site for instantaneous inclusion in the search index. Because JSearch reindexing occurs at variable frequencies depending on the resource (certain resources may be recrawled daily, while others are recrawled weekly or monthly), this tool is an effective way to provide an immediately improved user experience of search by instantly including sites in the search index. After a site is crawled manually, it is then added to the Seed List so it will be recrawled again at the scheduled time.

Figure 6. Manual Crawl dashboard showing several successful crawl jobs.

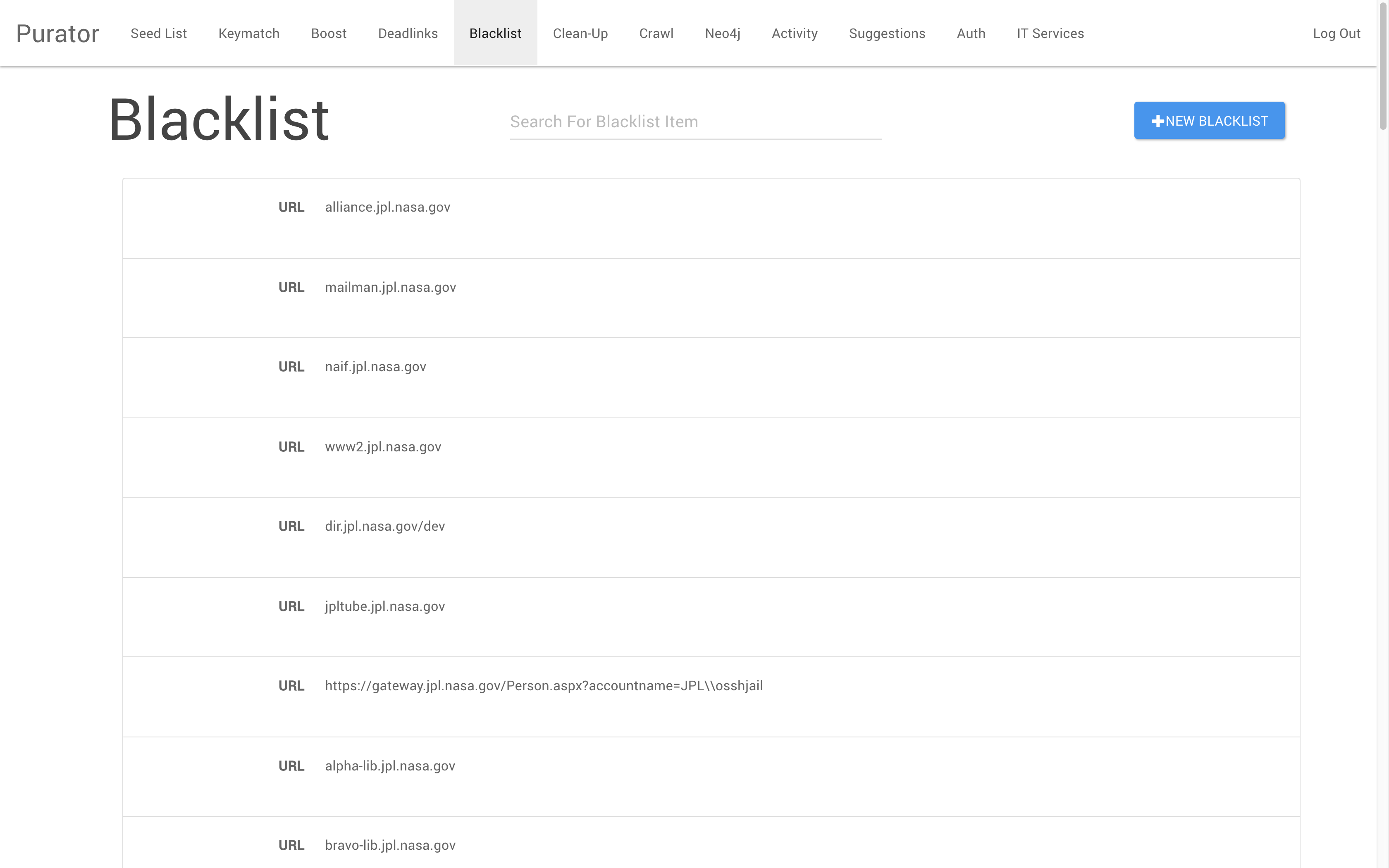

Clean-Up, Deadlinks, and Blacklist

The Clean-Up, Deadlinks, and Blacklist trifecta of tools is used by the knowledge curator to remove bad results from the search index. The Blacklist function is effectively the opposite of the Seed List; URLs added to the Blacklist are excluded from the regular recrawling and reindexing of JPL intranet content. While the Lab recommends the use of a robots.txt file on sites that do not wish to be crawled by the index, this practice is not completely adapted, and so the curator takes on the task of manually excluding sites which should not be indexed. The Deadlinks and Clean-Up functions are similar, but use differing methods to identify and remove bad links from the search index. The Deadlinks tool attempts to access sites, and then lists those which return a 404 code so that these ‘dead links’ can be reviewed and either ignored or deleted by curators. This human mediation of the dead links is intended to ensure that all deleted links are truly degraded, not just temporarily inaccessible. Finally, the Clean-Up function allows curators to remove links at the individual URL level. The tool searches the index for a single URL specified by the curator. If the URL links to a single page, then only that single result is made available for deletion. If the URL is more general, pointing to a site rather than to a single page, then all of the child pages under that URL are available for deletion. This allows for the instant removal of JSearch results which are not necessarily ‘dead links’ but which may, for various reasons, need to be removed from the search index. Accidental indexing of sensitive materials is one of those reasons.

Figure 7. The Blacklist tool.

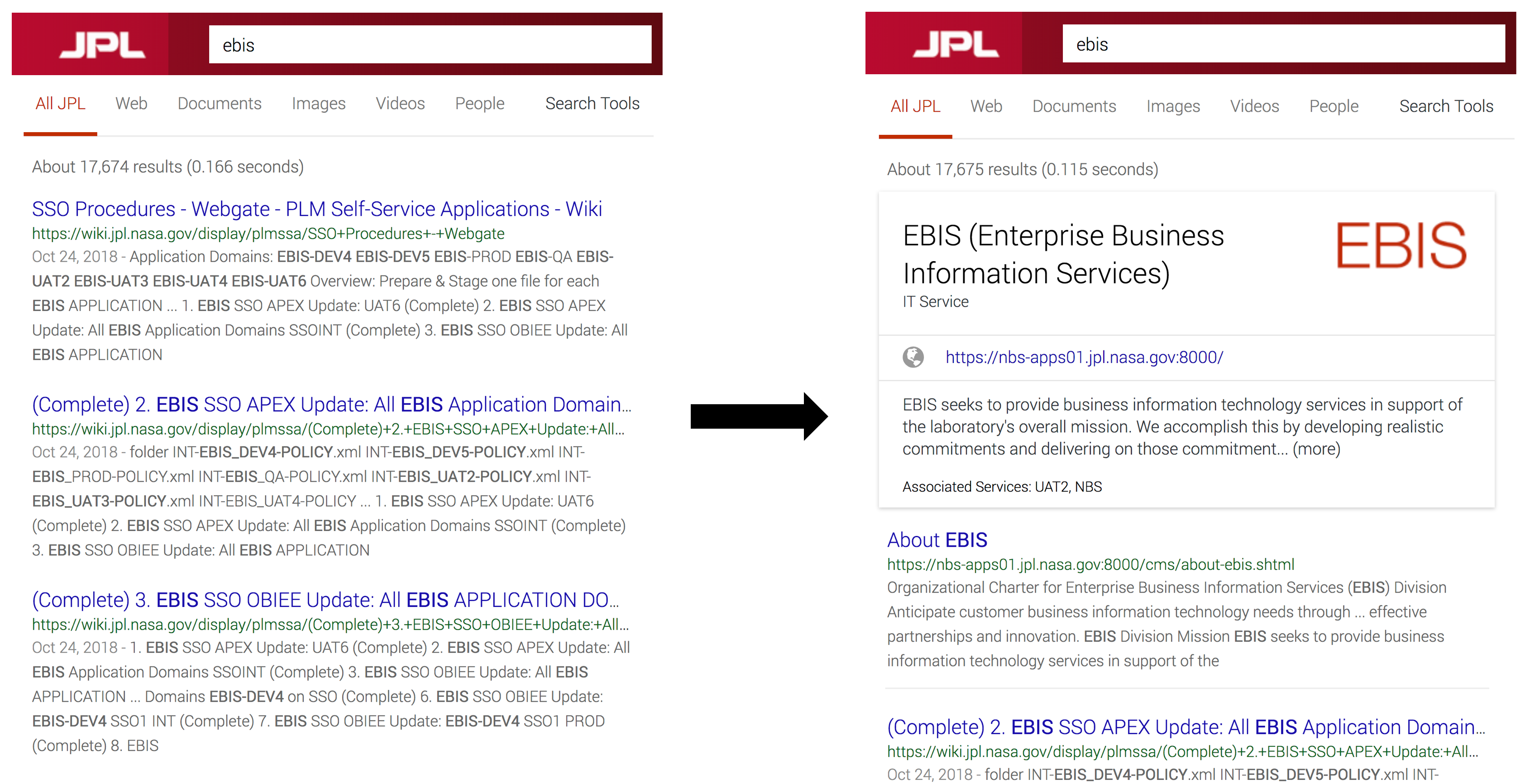

Over the course of the knowledge curator pilot, the student intern completed a “Top 100 Search Terms” project which involved manually improving results for the top 100 search queries according to search log data. Most of these top search terms could be considered “known-item” queries, since workers typically seemed to be searching for a tool or service that they know exists. Often, these searches are related to Lab technology (software, repositories, and other digital objects) or human resources and similar institutional policy. To improve results for these searches, the intern went through a multi-step process for each search concept. First, a knowledge card was created with a title, description, logo, and direct link to the resource. Then, one or two more results were keymatched; selected results were mapped to the keywords associated with a search concept. Typically, these keymatched results were mapped to pages about the known-item resource, providing contextual or how-to information “about” a given known-item. This method is meant to imitate the typical Google search results where the primary result is a card (which Google calls a “knowledge panel”) and the secondary result is a Wikipedia entry. An understanding of page metadata and knowledge worker search habits was a key asset for completing this task.

Figure 8. Image on the left is of organic search results retrieved by JSearch prior to any curation. Image on the right shows the same search results after curation, where the top two results are 1) a knowledge card, and 2) a link to a page “about” the known item.

Just as creating Portal categories in Wired identifies gaps in Wired content, looking to identify “about” pages for known-items within JPL’s intranet frequently reveals that no such page exists, or that information is scattered among many sites, some of which may be outdated. In this case, it is sometimes the search curator’s turn to become a content creator, by creating a Wired page to relate contextual and how-to information about a given resource. Having already gone through the work of locating relevant resources, search curators are well-poised to summarize and point to this information from a single resource. Furthermore, Wired integrates smoothly with the organic search, reducing the need for future manual keymatches. While most search curation tasks are manual, an understanding of the information ecosystem also provides mechanisms for interventions that will contribute to organic improvements. For example, adding more structured data to Wired pages will further enhance integration with JPL’s current and future search systems, improving both short-term and long-term findability.

3. Index as Intervention

Another responsibility explored under the knowledge curator role pilot, and the final part of the knowledge curator internship, is content management. While Wired serves as one platform for knowledge capture at JPL, it does not stand alone. There is a wide range of documentation produced by knowledge workers in the process of building flight hardware, which includes everything from test data to software code to drawings to review presentations. These information products are stored in a variety of in-house repositories, document stores, desktops, and shared drives. Much of this documentation is formally captured at the project level in an internal document library called DocuShare, a document store product from the Xerox corporation. However, this means that these documents are typically only available to individuals currently working on a particular project. An individual may even lose access to documentation he or she produced when transferred to a new project. As a result, it is not always easy for a team designing flight hardware for the Mars 2020 rover to view design documentation or test data for the same piece of hardware for the Curiosity Rover, even though it is likely that reviewing such documentation would provide valuable insights. This access rights issue impinges on JPL’s ability to effectively re-use enterprise content, even when it can be discovered via search and other means.

Access restriction is not the only barrier to effective re-use. Documentation in the earliest stages of project development, as well as in most stages of development for smaller projects, is less regulated by the institution. Interviews with knowledge workers reveal that teams and individuals may devise shared drive file structures, use other institutional tools such as Microsoft SharePoint, or simply store files on individual desktops and share by email. This ad hoc file management only serves to create further data silos in the long term, and limits the ability of search applications to utilize this content in a unified manner. Furthermore, this content is frequently lacking metadata and any other document-level contextualization. For example, though all mechanical parts at JPL are given a part identification number, many documents about that part do not include the part’s number, but rather include the descriptive name of the part. While knowledge workers may find a part name more user-friendly than an arbitrary number in the short term, but the name will very likely may have many variations, which can cause difficulty in searching across multiple platforms to find documentation related to a single part.

This area represents the final strategic intervention in which knowledge curators may engage to increase enterprise content findability. Information modeling serves as a starting point for identifying inconsistencies in metadata and storage practices. Facilitating the addition of a minimal standard metadata to documents as they are produced, as well as recommending where to store different types of files, for example, would greatly improve the eventual discovery and retrieval of these documents. Though the work done in this area over the course of the internship pilot was preliminary, knowledge curators at JPL have successfully created several proof-of-concept indexes which map siloed data to a single schema for easier, more unified content search and retrieval. This targeted content indexing, combined with the development and mapping of minimal standard metadata, is one way in which knowledge curators can help to break down silos as they occur in the enterprise.

User as Creator, Librarian as Curator

Information management at JPL has always put employees at the center of knowledge capture. As a 1999 JPL Knowledge Management Study Team document states,

While technology is an important ingredient to effective knowledge management, humans are the essential ingredient, both for knowledge production and for knowledge use. Any effective knowledge management process or system must add value that, in the minds of its users, exceeds the cost of its use. (Doane et al, 1999)

Viewed from the perspective of the user, knowledge management tasks must provide some tangible benefit in order to be adapted into workflows. As discussed above, there is a distinct role in “knowledge curation” that ought to be supported institutionally. However, that role does not stop at a single dedicated employee or even with a dedicated team – rather, every JPL employee that creates or uses digital content has some role to play related to institutional knowledge management.

When asked about this role that all JPL employees play in regards to content and knowledge management, JPL Deputy Chief Knowledge Officer Charles White noted that “everyone is a knowledge worker, they just don’t know it.” While knowledge management is valuable in any enterprise, the unique and pioneering nature of JPL’s work makes information capture and knowledge transfer essential to JPL’s continued success. As alluded to in previous sections, JPL employees frequently find themselves in the position of both information creator and information seeker, sometimes with regard to the same information object. However, without an adequate culture of knowledge capture, the content creation aspect is neglected and further complicates findability issues later down the line. Indeed, in order to perform knowledge management effectively, the institution ought to provide “practical guidelines to support all editors that create content to be published and found on the Intranet” (Findwise, 2016).

The siloization of content in a large enterprise is fairly inevitable, especially when an enterprise supports many different functions.The skillset of LIS professionals is uniquely poised to help break down those siloes by cultivating a culture of knowledge sharing and conveying information literacy principles to enterprise workers. Significant benefits are incurred when a workforce is instructed in best practices for interacting with an organization’s digital information ecosystem (Lucic and Blake, 2016). With an understanding of information-seeking behavior, metadata best practices, information architecture, and information literacy, LIS professionals can identify strategic interventions at every stage of the information lifecycle, and especially at the moment of content creation, that facilitate knowledge capture.

Conclusion

As organizations and their workers become increasingly reliant on shared digital resources to complete work tasks, librarians and other information professionals must decide what our roles will be in facilitating information capture and findability in an enterprise information ecosystem. While technology solutions must be part of any findability improvement plan, there is significant value that can be added at the content level, with interventions into existing workflows. These interventions ought to be strategic; that is, they must strive to align knowledge worker practices with organizational goals while minimizing impact on daily workflows. The strategy behind these interventions is part of what helps to ensure that any attempts to improve content findability will work not only in the short term, but in the long term as well.

JPL information managers have found that intervening strategically in the areas of document creation, enterprise search relevancy ranking, and document indexing are effective ways to improve enterprise content findability while simultaneously increasing knowledge workers’ understanding of their dual role as both content consumers and content producers. Indeed, part of the long-term solution for content findability issues comes from the knowledge workers’ improved understanding of their own role in the content lifecycle. This ownership of content creation, description, and storage is an important paradigm shift for knowledge workers whose daily work includes producing increasingly more valuable content for their organization’s digital ecosystem.

Librarians and other information specialists have a growing role in knowledge management, especially in the special library setting. This role is partially one of education; that is, information specialists within the enterprise have an expanding mandate to help create a culture of knowledge capture, and to demonstrate to knowledge workers that standardization and other principles of information management have a direct impact on the later findability and reusability of enterprise content. As the LIS field broadens and evolves, information specialists should continue to evaluate and expand upon the emergent role we have in improving institutional digital asset management, content findability, and knowledge management for the organization.

Bibliography

Athey, Jake. Getting to a Digital Asset Management ROI. Widen. 2009.

Bryan, L. Making a market in knowledge. McKinsey Quarterly. 2004.

https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/making-a-market-in-knowledge

Devereaux, A., Goldstein, B., Hanna, R., Martinez, E., Matthews, V., Powers, R., Seixas, B. Tompson, S. Strategic Outbrief: Functional Enterprise Documentation Working Group. 2014. 16 p.

Doane, J., Hess, S., Cooper, L., Holm, J., Fuhrman, D., U’Ren, J. A Knowledge management architecture for JPL. D-16577. 1999. 210 p.

Feldman, S, Sherman, C. The High Cost of Not Finding Information: An IDC White Paper. International Data Corporation. 2001. 10 p.

Findwise. Enterprise Search and Findability Survey 2016. 2016.

Seibert, M. 111 reasons why you need an enterprise wiki. 2010. https://www.atlassian.com/blog/archives/111_reasons_why_enterprise_wiki

Holm, Jeanne. Architecting an Approach to Knowledge Management. 2001. 25 p.

Leher, Mark. The Value of Descriptive Metadata to Improve Enterprise Search. A WAND, Inc. White Paper. 2013.

Lucic, A., Blake, C. Preparing a workforce to effectively reuse data. In Proceedings of the 79th ASIS&T Annual Meeting: Creating Knowledge, Enhancing Lives through Information & Technology (ASIST ’16). American Society for Information Science, Silver Springs, MD, USA, Article 75. 2016. 10 p.

Lustigman, A. Your Intranet Needs YOU: How Information Professionals Can Add Value to Intranets and Portals. Legal Information Management. 2015 Mar 19;15(1):57-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1472669615000171

Miles, D. AIIM Industry Watch Search and Discovery – Exploiting Knowledge, Minimizing Risk. Silver Spring (MD): AIIM; 2014. 34 p.

Schymik, Gregory, Karen Corral, David Schuff, and Robert St. Louis. “The Benefits and Costs of Using Metadata to Improve Enterprise Document Search.” Decision Sciences 46, no. 6: 1049-75. 2015.

Sweeny, Marianne. Delivering Successful Search within the Enterprise. Informer. 2012.

White, C. Personal Interview. 2018.

Wikipedia:Portal guidelines. Retrieved 09-21-2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Portal_guidelines

Wikipedia:WikiProject Council/Guide. Retrieved 09-21-2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:WikiProject_Council/Guide#What_is_a_WikiProject?

Wu, Mingfang, James A. Thom, Andrew Turpin, and Ross Wilkinson. “Cost and Benefit Analysis of Mediated Enterprise Search.” In Proceedings of the 9th ACM/IEEE-CS joint conference on Digital libraries, 267-76. Austin, TX, USA: ACM. 2009.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. An additional special thanks to Deputy Chief Knowledge Officer Charles White, OCIO software engineer Jeff Liu, and the JPL Search Team for their support in this work.

About the Authors

Rebecca Townsend (rebecca.m.townsend@jpl.caltech.edu) is an Information Management Engineer who began her career at JPL as the “knowledge curator” intern. She received her MLIS from UCLA in 2018, and has a background in Romance languages and anthropology. Her primary research interests include wiki maintenance and information literacy.

Camille Mathieu (camille.e.mathieu@jpl.caltech.edu) is in Information Science Specialist with the JPL Beacon Library. She received her MLIS from UCLA in 2015, and has a background in English literature. Her primary research interests include enterprise search improvement and metadata for content management.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply