by Kyle R. Rimkus, Alex Dolski, Brynlee Emery, Rachael Johns, Patricia Lampron, William Schlaack, Angela Waarala

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic made itself felt across the University of Illinois system on March 11, 2020 with the official announcement that its three campuses in Chicago, Springfield, and Urbana-Champaign would immediately migrate to online teaching and prohibit all work-related travel. [1] Nine days later, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker issued a statewide stay-at-home order. [2] In response, the Libraries at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign closed their doors to patrons with the expectation of reopening on April 7, 2020. [3] However, as we write this article in May of 2021, all Library buildings remain, with some restricted exceptions, shuttered to the public. The university has shifted the predominance of its operations to online teaching, learning, and remote work where possible (with the hope and expectation of easing these restrictions during Summer 2021).

In response to the university’s shift to distance learning, the library took a series of measures designed to extend services to remote patrons who sought access to collections materials. In early April, 2020, the university announced the summer semester would be fully remote [4], and the Library announced its participation in the HathiTrust Emergency Temporary Access System, or ETAS [5] (more details on ETAS implementation to follow).

In June, a fully remote Summer semester and an anticipated remote or hybrid Fall semester looming, the library began devising a plan to meet the collection “fulfillment” needs of students. On June 2, the university allowed certain campus units to return to on-site work in a restricted capacity [6], with provisions for employee COVID-19 testing [7]. While the library remained for the most part closed to the public, the university allowed staff members who maintained their testing protocol to work on-site in socially distanced conditions.

On August 11, 2020, the Library formally announced its policy for an “electronic-first” fulfillment strategy. [8] This policy prioritized the purchase of e-books over print when available, and specified that books available in the HathiTrust ETAS would not circulate to patrons. It also meant that the library would digitize items unavailable through e-book vendors or ETAS and make the digital surrogates available to patrons in a restricted manner. For this reason, the library set to work beginning in June 2020 to introduce a new mode of providing patrons virtual access to books. Our “emergency access” approach went live on July 20, 2020, and persists to the present (May, 2021). However, an end may be in sight. The university has suggested a return to a residential teaching and learning model for Fall, 2021, and the Library intends to follow suit by turning off the HathiTrust ETAS and transitioning away from full-fledged emergency access policies and procedures in early summer, while keeping some on-demand digitization services in place for remote students and faculty.

Brief Literature Review

The subject of this paper, one library’s approach to providing access to materials during a pandemic, is timely given that little has been published to date on the subject. A paper has been published on the topic in this journal [9], and we expect to see similar reports and analyses in the months and years to come as more librarians reflect on the services they altered or introduced in 2020. The subject of controlled digital lending, while not quite the same as what we in this article are calling Emergency Access Digitization, did loom large in our minds as we planned for and implemented our solution. While we did not conduct a deep literature review on this subject, one white paper in particular served as an important reference for our understanding of laws related to providing restricted online access to works protected by copyright [10].

The Emergency Access Workflow

The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) Library’s approach to providing patrons with access to circulating print materials during the pandemic consisted, from a bird’s eye view, of the following:

- In the library’s online catalog (powered by Alma/Primo after a recent migration from Voyager [11]), we enabled the HathiTrust ETAS. If an item was available there, the print item would not circulate and patrons were obliged to “check it out” virtually to gain restricted online access.

- For items not available in the HathiTrust ETAS, patrons would request access to books in the library’s online catalog and specify in their request form whether they preferred print or digital format.

- For print requests, the library placed items in lockers on site in the library for patrons to pick up in person.

- For digital requests, the library digitized items and made them available for online viewing in a restricted manner, prior to depositing them into the HathiTrust Digital Library.

As simple as this approach may sound, its execution required detailed planning and constant refinement. As this article focuses on digitization, we will outline our entire process while placing an emphasis on what went into initiating an on-demand Emergency Access Digitization service. Our process is best understood in two workflow diagrams that demonstrate what happened when patrons requested a book from our catalog. The first diagram (Figure 1) breaks down the steps leading up to what will be the focus of this paper and is the subject of the second diagram (Figure 2); that is, the workflow for items after they had been identified for digitization.

Figure 1. First steps of the Library’s digital-first fulfillment strategy (adapted from a diagram created by Mary Laskowski).

As Figure 1 shows, the fulfillment process always began with a patron catalog request, and with staff from the item’s owning library verifying whether the item was already available in electronic format. If it was not, they pulled the item and routed it in a shipping bin to Preservation Services in the Main Library, where staff either routed items to lockers for in-person pickup or digitized them for online access. To the greatest extent possible, Preservation staff sought to honor patrons’ access format preferences for print or digital, which was indicated in the patron’s request form in the “Is digital or print access preferred? Other info?” field. However, certain physical considerations made digitization impractical (e.g., books with very tight spines or an abundance of foldouts), and these items were routed directly to lockers. For more detail on this process, Figure 2 below breaks down all of the steps taken in Preservation Services once we received a book:

Figure 2. Triage, digitization, and access workflow.

HathiTrust ETAS Access

Our goal was to deposit digitized books into the HathiTrust Digital Library, where, if they were protected by copyright, patrons could gain limited and restricted access to them. According to its website (https://www.hathitrust.org/ETAS-Description), the ETAS

“permits special access for HathiTrust member libraries that suffer an unexpected or involuntary, temporary disruption to normal operations, such as closure for a public health emergency, requiring the library to be closed to its patrons, or otherwise restrict print collection access services.

The service makes it possible for member library patrons to obtain lawful access to specific digital materials in HathiTrust that correspond to physical books held by their own library. The Emergency Temporary Access Service will enable many HathiTrust member libraries to continue supporting the teaching, learning, and research mission of their institutions during said disruption in service.”

In the UIUC Library’s announcement of adopting a “digital-first” approach to library item fulfillment, we clarified that “Students, faculty, and staff may log in to HathiTrust and view all volumes that HathiTrust has verified as being held in our print collection, even if in copyright. Users can read and search the book online, but they will not be able to download the book in full,” and assured patrons that, “Through the ETAS, our faculty, staff, and students now have reading access to 46.65% of our print collection (based on overlap data generated by HathiTrust staff from the most recent catalog update we supplied to them).”

In practice, this meant that when patrons discovered the catalog record for an in-copyright book that was available in the HathiTrust ETAS, they were unable to check it out in print format, but could click on a “Full Text Available in HathiTrust” link in order to gain restricted access to a digital surrogate of the item (Figure 3). We made HathiTrust links available in the catalog using a Primo ad-on that matched the record’s OCLC numbers with OCLC numbers for items in the HathiTrust Digital Library [12].

Figure 3. Links to non-circulating items available in HathiTrust ETAS in the Library catalog.

On clicking the HathiTrust link, the catalog routed users to the HathiTrust ETAS, where they were prompted to “check out” the work for one hour at a time.

Figure 4. HathiTrust ETAS item checkout prompt.

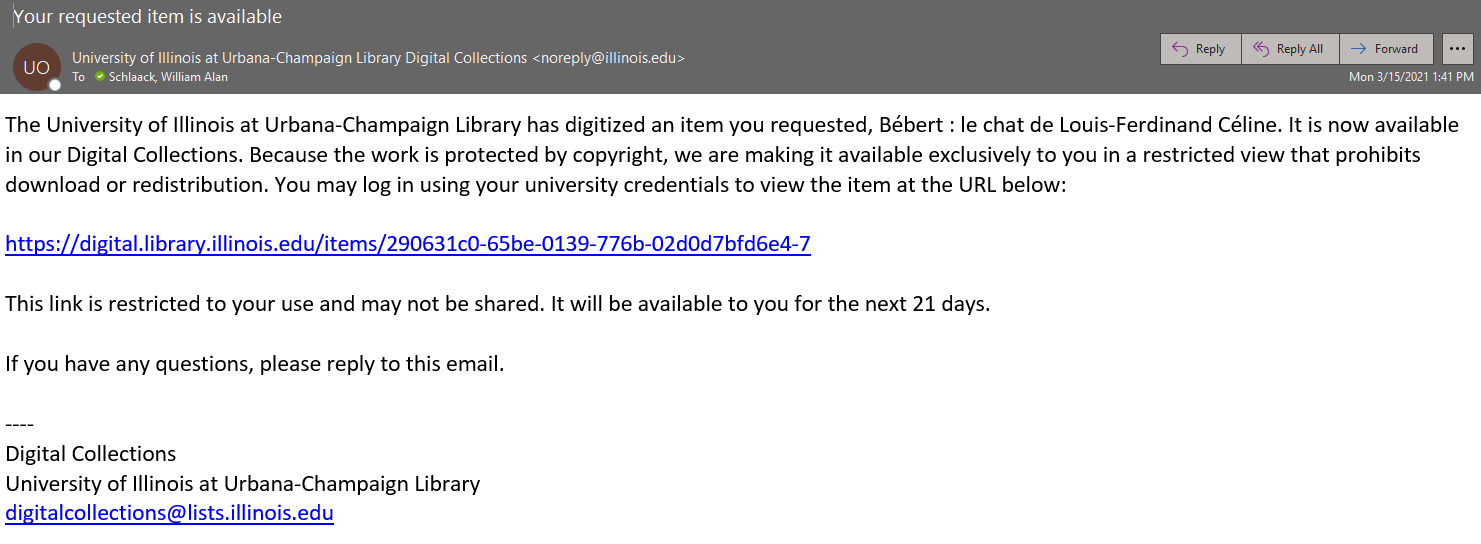

Once accessing the item in HathiTrust, the patron could turn pages to view and read using the system’s native item viewer (Figure 5). Due to copyright restrictions, the ETAS viewer did not allow advanced features such as downloading page images.

Figure 5. The HathiTrust ETAS item viewer.

The End User Experience

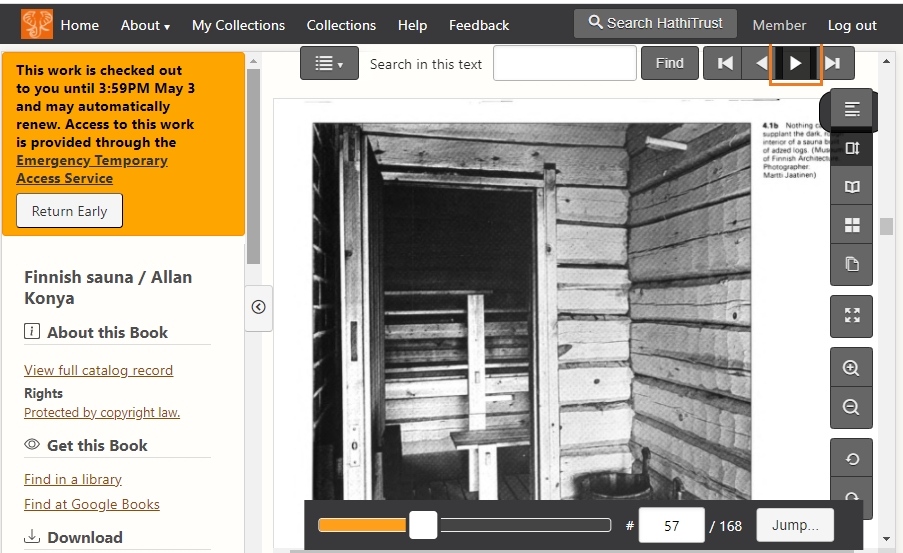

The Library’s goal was to fulfill all patron requests within 14 days. Once an item arrived in Preservation Services, it generally took one day to route to a locker. Digital requests required one to five days to digitize and one additional day to ingest into our access system and make it available to the patron. From there, it took one to three days to deposit into HathiTrust and two additional days for HathiTrust to ingest the item and for us to update our catalog with a link to the item for broader patron access. While the HathiTrust ETAS was the end point for all digitized items, patrons were provided interim access to the digitized content in our local Digital Collections platform in order to meet their needs as swiftly as possible. As mentioned above, the process began with a request from the catalog (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Library catalog request form.

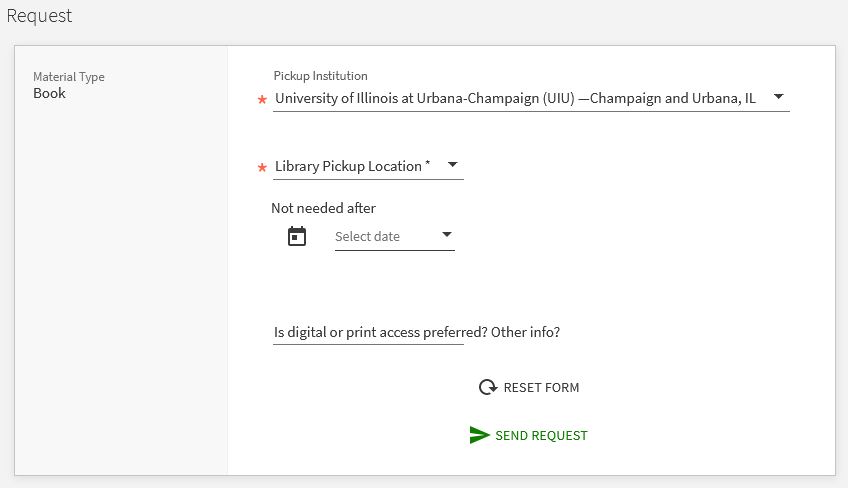

After specifying a preference for digital format and clicking “Request,” staff sent a courtesy email stating that the item had been accepted into the local digitization queue (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Email confirming item has been placed in digitization queue.

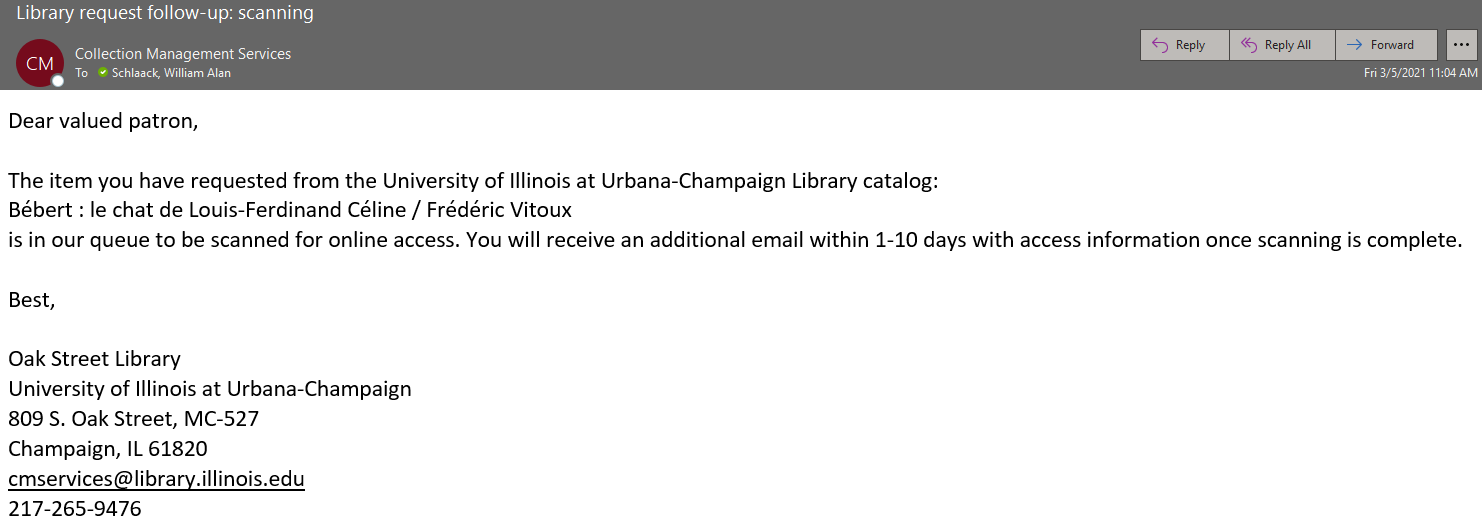

Upon digitization, patrons received another automated email, this one from our Digital Collections platform, notifying them of the availability of their requested item (Figure 8). (To note: we will detail the technology we used to digitize and make items available in the Digital Collections platform in the section “Digitization” below).

Figure 8. Automated email confirming availability of digitized item.

Once authorized, the patron encountered a digital object page similar to others in the Library’s Digital Collections platform [13], but stripped of page elements we provide for open access items such as a download feature and citation links (See Figure 9 and, for implementation details, the section entitled Digitization below). We granted patrons exclusive access to their requested items on this platform for 21 days, after which all items became broadly accessible to the requesting patron and others in the HathiTrust ETAS.

Figure 9. Patron access in the UIUC Digital Collections platform.

Communication and Work Tracking

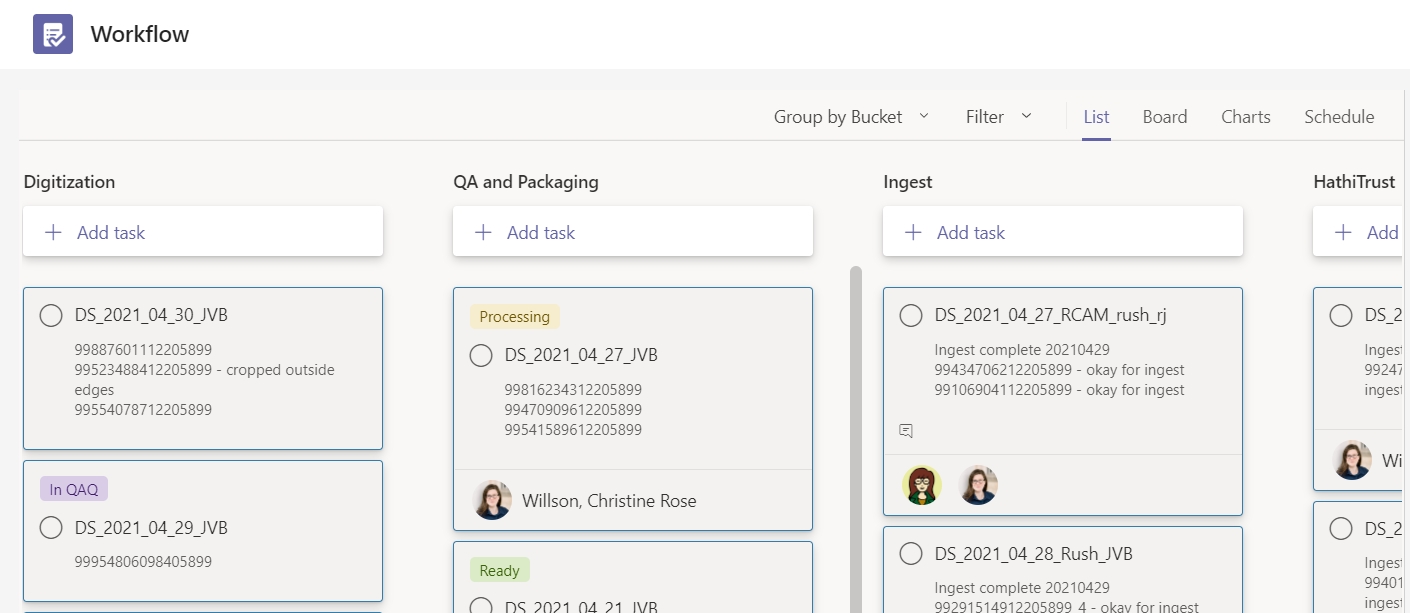

For local communication, we established an Emergency Access Digitization space using an instance of Microsoft Teams (Figure 10). Here, we managed project communication, housed a manual that defined our policies and procedures, and tracked workflows. We also established a shared email list to simplify library-wide communication on the topic of Emergency Access Digitization.

Figure 10. Workflow tracking in Microsoft Teams.

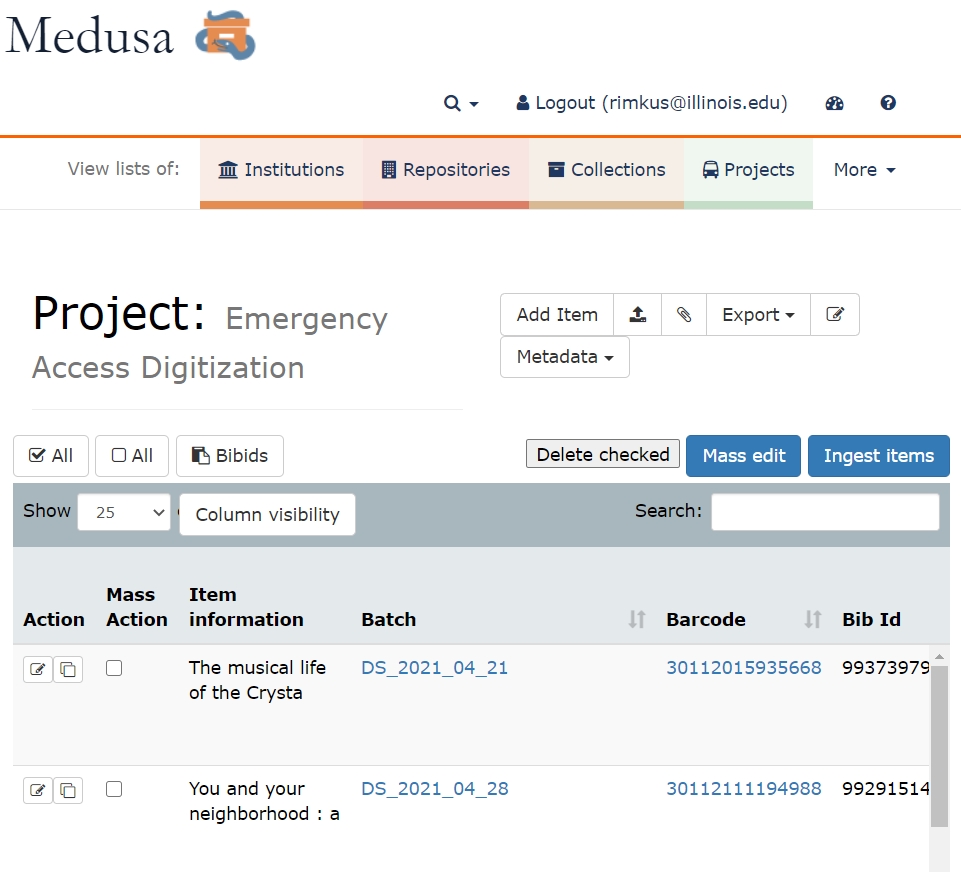

All items that came through Preservation Services were tracked using the “Project” feature of our Medusa Digital Preservation platform (Figure 11). We developed this feature for queuing up items for preservation digitization prior to the pandemic, but were able to adapt many of its features to serve this project such as scanning item barcodes and importing catalog metadata.

Figure 11. Tracking items queued for digitization using the “Project” feature of the Medusa digital preservation repository.

Digitization

The UIUC Library’s Internet Archive scanning center played a modest role in this project, digitizing 39 out-of-copyright items. The University Library has hosted its Internet Archive scanning center on site since 2007. The number of scanning stations in the center fluctuates based on need, but currently the Internet Archive operates three scanning stations supported by three full-time staff. During fiscal year 2019, the scanning center digitized 1,179,650 pages and 4,841 items total.

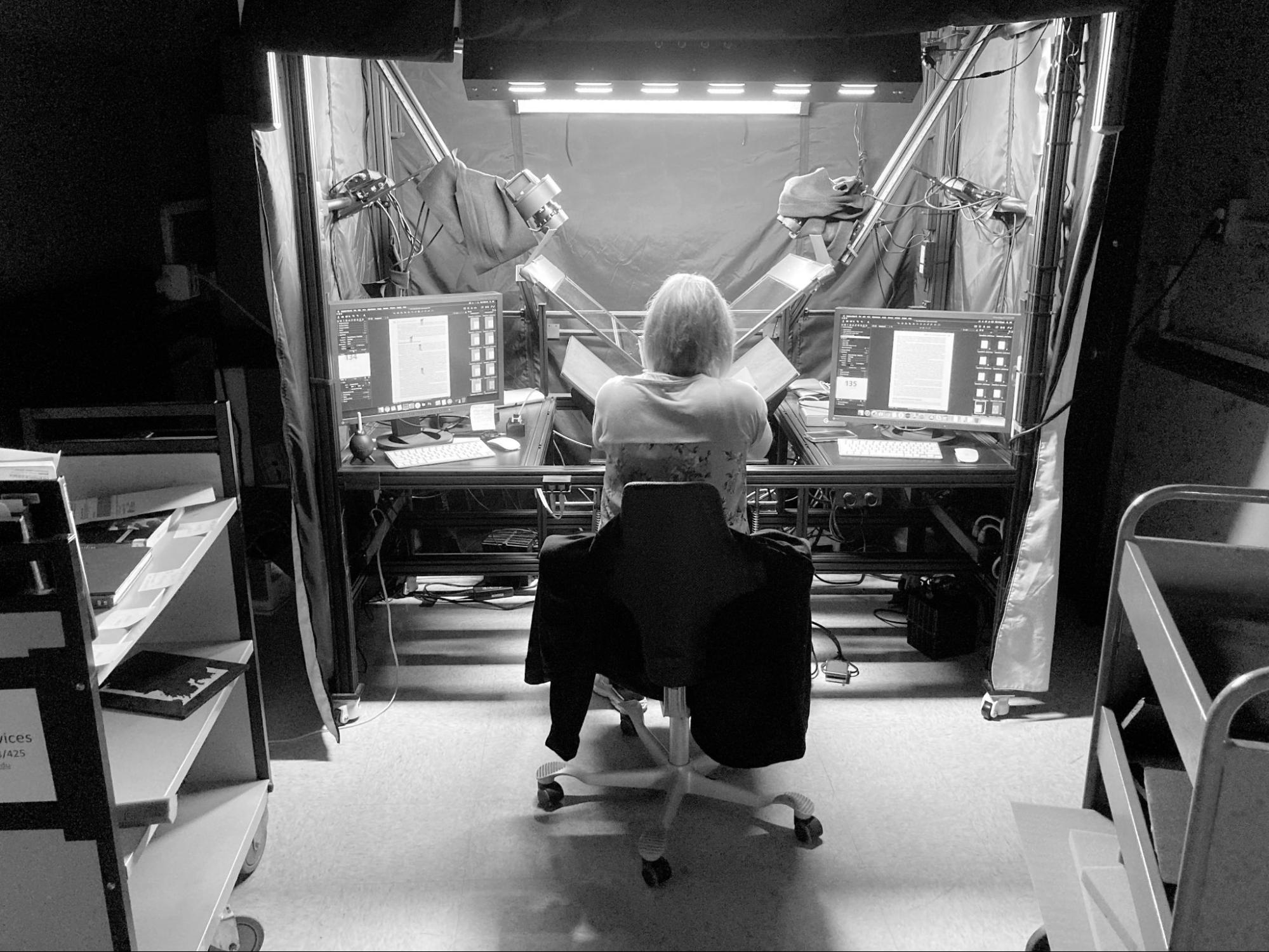

We digitized the majority of items for this project (764) in our own Digitization Services group, which is housed in the Library’s Preservation Services unit. Operationally, Digitization Services staff reformat visual materials, primarily in print and paper-based formats, for preservation and access. Prior to the pandemic, the group was managed by one Academic Professional, with one full-time Civil Service Digital Imaging Specialist, one half-time graduate assistant, and occasional hourly workers. Over the course of the pandemic, the group was able to complete the long-planned hiring of a second Digital Imaging Specialist. To meet demand for Emergency Access Digitization, the group took on two temporary transfers of Civil Service library staff to serve as interim Digital Imaging Specialists, and hired an Extra Help worker to provide imaging and workflow support.

For Emergency Access Digitization, Digitization Services staff relied on a variety of imaging equipment to complete their work. Their work horse was an imaging station called the BC100, which had previously been used primarily for special collections materials like bound rare books, pamphlets, and historical theses and dissertations (see Figure 12). The BC100 [14] is a dual-camera system with Phase One P65 camera backs, Northlight LED lighting, Schneider APO-Digitar 90mm f/4.5 lenses, Eizo color-calibrated monitors, and Mac Mini workstations. BC100 digitization operators use a pneumatic book cradle and foot pedals for platen control and remote triggers to make exposures. Digitization Specialists used Capture One CH photo editing software to capture raw image files with digital cameras tethered to Mac Mini computers via Firewire. They controlled camera settings remotely through a secondary application called DTDCH Shutter Integration Solution. Autocrop functions and custom Apple scripts in this software helped increase productivity and efficiency via automation of repetitive processes [15].

Figure 12. The BC100 imaging station in action.

The BC100 was not the only equipment we used for Emergency Access Digitization. In the first months of the project, we borrowed a piece of equipment known as the Knowledge Imaging Center Bookeye (Figure 13) from a public services unit in the library closed due to the pandemic. Built as a walk-up digitization kiosk for library patrons unskilled in advanced digitization, we found the Bookeye poorly suited to the sort of high-volume, high-quality production work we sought to do, primarily because its interface provided many barriers to control by an advanced operator, leading to cumbersome file processing, not to mention that the Bookey’s page images were on the lower end of acceptable quality for our required specifications. We ceased using this machine as soon as we were able to procure additional imaging stations better suited to our needs. While we expect that the Bookeye system will serve a valuable need as a walk-up digitization kiosk for library patrons, we cannot recommend it for use in a digitization lab environment.

Figure 13. The Bookeye scanning kiosk, which we used briefly but concluded was unsuited for our needs.

To meet the rising demand for digitized Emergency Access materials, we began planning in October, 2020 to procure a “do-it-yourself” imaging station built from equipment and materials available on the consumer market, and an additional station built from a combination of consumer-market and speciality-market components. While we hoped to have these two stations ready by December, 2020, it wasn’t until early 2021 that we had all of the equipment in place. This was due primarily to purchasing and shipping delays related to the pandemic, as well as the challenge of fitting new imaging stations into a room formerly used as office space. Library Facilities, IT, and Shipping were integral to adding new equipment, keeping staff safe, and solving logistical puzzles.

After much rearranging of our office and lab spaces, we were able to install the two new imaging stations housed in box-shaped black canopy tents for control of lighting. The “DIY” station (Figure 14) features a Kaiser Book Copy Easel cradle on a Beseler copy stand Canon 5DSR, a 24-70 2.8 Canon lens, and Rotolight Anova Pro LED Lights set on continuous mode at 100% and 5500 Kelvin color temperature. We found these lights adequate for general collection image quality needs, but not powerful enough for higher-quality special collections workflows. In order to offset their low power output, they require a higher ISO than is optimal for the camera.

Figure 14. The “DIY” imaging station, built primarily of consumer-market components.

The second additional station (Figure 15) uses a Digital Transitions Atom [16] copy stand equipped, based on image quality needs, with a Canon 5DSR or a P40 PhaseOne Medium format digital back we had on hand with a Schneider lens. This station utilizes Digital Transitions Photon LED continuous lights tethered into Capture One for Phase One software [17].

Figure 15. Imaging station built of consumer-market and speciality-market photography equipment using a Digital Transitions Atom copy stand.

In order to simplify training for new staff, we decided to adapt local digitization and file packaging processes already in use in our special collections workflows for Emergency Access Digitization. As ingest into the HathiTrust Digital Library was our goal and we had no interest in taking up more server space with temporary files than was needed, we decided to photograph all page images to meet HathiTrust specifications rather than our own higher standards for special collections preservation digitization. This meant producing files at 8-bit bit-depth and 400 dpi, as opposed to 16-bit images shot at 600 dpi or higher for special collections materials. Furthermore, since long term preservation was not a priority for emergency access items, our staff streamlined unit quality control procedures to prioritize user accessibility over perfectionism. In practice, this meant occasionally compromising on technical standards such as exposure or white balance for the sake of providing a complete, readable copy of the material for users to access as quickly as possible. While we compromised on the in-house standards we use for imaging special collections materials, we made sure to meet HathiTrust’s lower but still sufficient quality standards for digitized general collections.

For the past three years, staff in Preservation Services have worked with Digital Library Technical Coordinator Henry Borchers to develop Speedwagon [18], a GUI-based software tool that pulls together a variety of file processing scripts used to generate properly packaged items for deposit into repository platforms (Figure 16). Our HathiTrust packaging workflow included generating Optical Character Recognition transcript text files for each page image, validating IPTC and EXIF metadata to ensure these met HathiTrust specifications, creating a YAML file to indicate the title page for each item, pulling MARC records from the library catalog in MARC XML format, and generating a checksum hash for each object. With Speedwagon, we were able to efficiently generate these file packages. Speedwagon was built using Python 3, PyQt for generating its graphical user interface, Google Tesseract for generating OCR, Exiv2 for examining embedded image metadata, and Kakadu for creating JPEG2000 images.

Figure 16. User interface for Speedwagon, a tool for processing packages of images post-digitization.

After performing necessary quality control and post-processing on our digitized book file packages, we deposited our digitized files in our in-house-developed Medusa preservation repository, where they received globally unique identifiers, regular backups, and integrity checks. From there, we ingested them into our companion Digital Collections platform, which incorporated them into structured digital objects. The Digital Collections platform leverages the open-source UniversalViewer [19] to provide convenient pagination through multi-page digital-objects and deep-zooming of individual pages.

Early conceptions of a delivery system for limited and restricted access to digital objects imagined a custom, purpose-built standalone application alongside our existing Digital Collections [20]. Ultimately, we decided to build on the extensive infrastructure already in place in our Digital Collections platform related to the features mentioned previously. This minimized redundant development work and enabled staff to leverage their familiarity with our existing infrastructure. The first step in this direction was to modify the digital object entity in our Digital Library to add a Boolean “restricted” flag. Such objects are suppressed from browse, search, and harvesting results, and unavailable to unauthorized users in all other respects. Next, we added an access control list of patron IDs corresponding to access-expiration dates.

After a book is ingested into the Digital Collections, it is set as restricted and the requesting patron is added to the allow list with an access-expiration date of 21 days in the future. When a patron ID is added to an access list, the Digital Collections system sends an email to the corresponding email address containing the URL of the item to which access has been authorized. Attempting to dereference this URL requires authentication via the campus single sign-on (SSO) provider, which sends a patron ID back to the Digital Collections platform and conditionally grants access depending on the access-expiration date.

Analysis

We began gathering usage statistics on the Emergency Access Service’s start date of July 20, 2021. We anticipate shutting down our emergency access protocols at some point in the summer of 2021, but for the purpose of bringing our paper to publication in a timely manner we present our data with a cutoff date of April 20. Taken in all, during this nine month period we received 3,083 patron-requested items in Preservation Services. Of these, based most importantly on whether the patron expressed a preference for print or digital:

- We sent 2,100 items to lockers for in-person pickup in the Library (68% of all requests).

- We digitized 803 items for online access (26% of all requests).

- 39 items were in the public domain; these were digitized in our in-house Internet Archive scanning center and made freely available in the Internet Archive and then deposited in HathiTrust.

- 764 items were still protected by copyright; these were digitized in-house by Digitization Services and made available to requesting patrons in our own local Digital Collections platform, with eventual limited access in HathiTrust Emergency Temporary Access System (ETAS). These items total 191,372 pages digitized on-site.

- We withdrew 180 items from the digitization queue due to their prior availability in electronic format or removed them due to other errors in workflow routing (6% of all requests).

Figure 17. Pie chart showing outcomes from nine months of Emergency Access Services.

Table 1. Emergency Access production statistics by the month.

| Month (“July” represents July 20-August 20) | Total books routed to Preservation | Books sent to lockers | Books removed from digitization queue (already available in electronic format elsewhere) | Books digitized by Internet Archive (out of copyright) | Books digitized in-house (in copyright) | Total books digitized |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July | 34 | 23 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| August | 598 | 519 | 14 | 5 | 60 | 65 |

| September | 520 | 405 | 21 | 4 | 90 | 94 |

| October | 417 | 300 | 22 | 4 | 91 | 95 |

| November | 308 | 176 | 25 | 3 | 104 | 107 |

| December | 131 | 51 | 15 | 2 | 63 | 65 |

| January | 424 | 277 | 26 | 8 | 112 | 120 |

| February | 351 | 204 | 27 | 4 | 116 | 120 |

| March | 300 | 145 | 29 | 4 | 122 | 126 |

| Total | 3,083 | 2,100 | 180 | 39 | 764 | 803 |

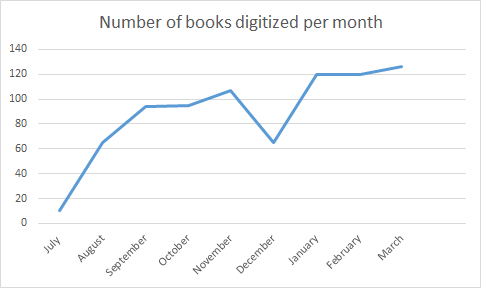

It is interesting to note that in the first three months (July-September) we found ourselves digitizing about 15% of all requested items. As we transitioned to the second half of the 2020 Fall semester we expected to see a rising demand for digital access in response to the university administration’s request that students leave campus November 20 and not return for the remainder of the Fall semester [21]. For this reason, we added new digitization staff and equipment to the project. Indeed, from October to December we digitized 31% of all items to keep up with patron demand for remote access in digital format (of note all requesting features were shut off completely for a two week period in December for winter break, which explains the dip in production volume during that time). From January to March, we digitized 34% of all requested items to meet demand.

Figure 19. Number of books digitized per month.

Over the entire nine-month period, the numbers average out to 26% of all requests evincing a preference for digital access, 68% specifying a preference for physical access in lockers, and 6% of items being located as ebooks already available elsewhere. There’s a bit of ambiguity in these numbers since not all patrons made it known which format they prefer, and in these cases we may have digitized items or sent them for locker pick-up based on our scanning capacity. However, since our process focuses on making sure to digitize at least everything people request for online access, to the best of our knowledge these numbers seem to reflect patron demand.

Figure 20. Patron preference for locker pickup vs online access.

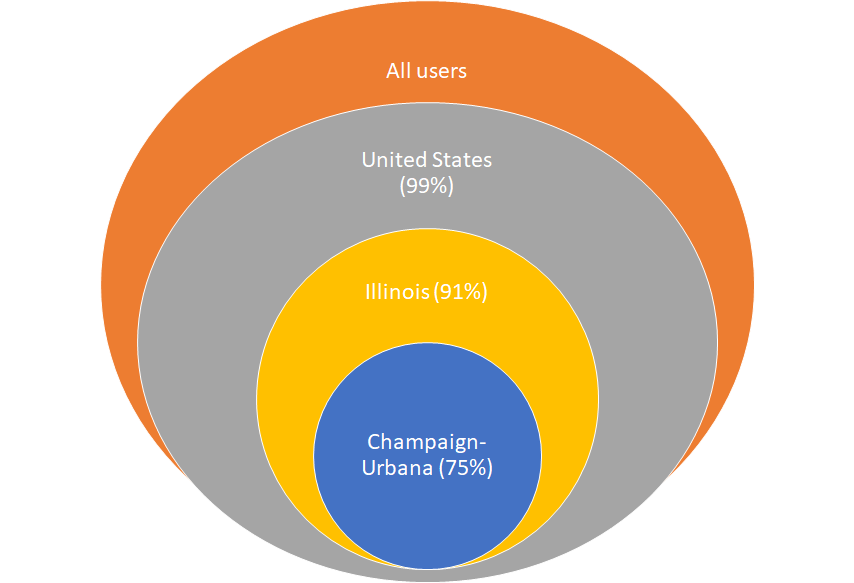

Given the circumstances of our largely remote teaching and learning environment, we were also curious to know if those taking advantage of the Emergency Access Digitization service were doing so from far-flung locations. As we have Google Analytics running on our Digital Collections platform, we were able to take a list of all URLs sent to library users of Emergency Access Digitization and use the Google Analytics API to return a dereferenced list of their geographic locations. This data set is ambiguous due to the fact that some users may have been using campus-provided VPN technology in order to appear “on campus” and thus better able to access all university online services, and others may have been using VPN simply to obscure their location. Also, Google Analytics may not track users who have an anti-tracking browser plugin installed. With these caveats in mind, the web analytics data seems to suggest that the majority of users who utilized this service were local to Illinois (91%, with 75% in Champaign-Urbana), but that a meaningful (9%) portion of them from out of state, not to mention 1% out of the country, benefitted from remote access during the pandemic.

Figure 21. Online access by patron IP Address location.

Challenges, Lessons Learned, and Next Steps

We were able to implement a robust Emergency Access Digitization service within a month’s time due to several factors. Most importantly:

- We have asserted control over our information technology infrastructure for many years. As a library, we have resisted the trend prevalent in many peer institutions of outsourcing information technology infrastructure to external vendors or to campus-level IT units. (This is not to say we have not embraced technical change; we have become campus leaders, for instance, in implementing cloud services in favor of local server administration). In the case of implementing Emergency Access Digitization, this allowed us to get to work straightaway on a needed solution without having to labor through the red tape and inflexibility of external partners.

- We have deliberately built flexible tools and services for managing digital content and production workflows. Over the years, we have designed our repository architecture and workflow tools with adaptability in mind, so that with minor changes they can accommodate new needs as they arise. From a design perspective, this has meant giving simplicity right of way over complexity whenever possible for the sake of future adaptability to multiple uses. In many cases, this has meant eschewing popular open source repository platforms over the years after finding their design intractably complicated and instead choosing to build our own.

- We were willing to take on modified roles and challenging circumstances during the pandemic. Throughout the library, multiple people took on modified work roles in order to implement this new service. This included two temporary library staff transfers to the Preservation Services unit to serve as Digital Imaging Specialists. Notably, this project pushed many people who had worked in a back-of-the-house technical services role into closer front-line contact with patrons than ever before, and required close collaboration with Facilities and IT to adapt work processes both on premise and remote. Flexibility and cooperation were key in building a new team to implement the workflow, both for training new staff with little photography experience and adapting quickly.

Implementing Emergency Access Digitization was certainly not without challenges. Principally among these, we would note:

- Disentangling individual digitization requests from needs related to course reserves and reading lists. Certain instructors sought to use this process for course reserves. Requests for digitization of portions of print materials were routed through the Interlibrary Loan and Document Delivery webpage [22]. The digitization of entire works for the purpose of course reserves was not recommended due to copyright restrictions; however, in Preservation Services, we were generally able to digitize full in-copyright works for limited access in HathiTrust ETAS if we had enough advance notice. Since these items would be accessed by multiple people, our goal was to get them all into the HathiTrust ETAS in a timely fashion.

- Communicating with patrons displeased with the library’s “digital first” approach. Some patrons preferred physical copies of books. While many patrons expressed their appreciation for gaining online access to library materials, there were others who vehemently complained about the library’s pandemic policy that gave preference to digital.

- Informal user feedback gathering. A method to aggregate feedback from our users would have been helpful from the start. In retrospect, it would have been wise to build a user feedback option into our interfaces in order to better understand how library users experienced our “digital-first” strategy during the pandemic. As it stands, we have received a variety of positive and negative feedback, but this has occurred in too scattershot and adhoc a manner to be useful.

- The pandemic made everything slower and more complicated than usual. While we were able to implement this service in short order, we had to work through significant slowdowns when ordering and shipping new equipment and furniture or fixing broken equipment. We also had to reorganize space to comply with safety precautions due to COVID-19 and fit in two new equipment stations to support this work.

Taken in all, this paper gives an overview of Emergency Access Digitization services as they existed from July 20, 2020 to April 20, 2021. Looking ahead, we intend to turn off the HathiTrust ETAS on June 13, 2021 and transition to some form of controlled digital lending for those still unable to come to campus and access items in print format.

Acknowledgments

This was an all-hands-on-deck operation involving multiple people at the UIUC Library. Colleagues in our many departmental libraries adapted to Alma and routing materials to Preservation following this new procedure. William Schlaack, with Shelby Strommer advising on collections care, came into the library while many people were working remotely and took the lead on triaging materials once they arrived in Preservation Services.

Rachael Johns led digitization efforts in Digitization Services, aided from December on by Tabby Garbutt and Christine Willson. Rachael’s work included overseeing daily operations and training two staff members from different areas of the library who worked temporarily in the Preservation Services unit: Johna Von Behrens and Diane Griswell. They mastered digitization work using complicated equipment and processes, and did excellent work as digitization technicians.

Julie Bumpus and Preston Wright of Collection Management Services took on doing an additional review of whether items were available in digital format prior to digitization. Tricia Lampron in Acquisitions and Cataloging Services (ACS) ingested digitized books and metadata into our local access platform. Digitization Services Graduate Assistant Brynlee Emery performed quality review of materials and deposit with HathiTrust. Brian Clark and later Greta Heng from ACS updated our catalog with links to items once they become available in the HathiTrust ETAS.

From the Scholarly Communication and Repository Services group, Alex Dolski worked to modify our local Digital Collections platform so we could deliver items to one patron at a time in the restrictive fashion this project required. Colleen Fallaw fixed problems as they arose with our back-end Medusa system, and Seth Robbins coordinated these efforts. In Preservation Services, Henry Borchers wrote scripts to allow us to retrieve MARC metadata in XML format from Alma for the proper packaging of our HathiTrust submissions. In IT, Jon Gorman helped Henry understand the technical workings of Alma to make this happen, while Eric Mosher, Jason Strutz, Anthony Stewart, Rhonda Jurinak, Jim Dohle, and Lee Galaway all helped make sure everything was properly in place with the many complex hardware, software, network, and storage components in play.

Staff in Circulation have been in constant communication with staff in Preservation to make sure patron needs are fully met, and Janelle Sanders helped those of us not familiar with Alma to understand its intricacies. Norris Purdy, Dillon Brown, and Brian Agnoletti in Shipping and Receiving helped coordinate the routing of materials and followed up on special requests. Timothy Newman and Lesli Lundquist from Facilities aided in coordinating new furniture and room arrangements. Mary Laskowski, Cherie Weible, Chris Prom, and Jennifer Teper did a fair amount of wrangling behind the scenes to put our high-level approach into place. Taken in all, this project was a massive effort that involved committed collaboration from all areas of the library, and we salute everyone involved.

About the Authors

Kyle R. Rimkus

Kyle Rimkus is Preservation Librarian with rank of Associate Professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library, where he leads efforts to establish policies, technologies, and practices to ensure that digital collections will persist into the future.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9142-6677

Alex Dolski

Alex Dolski is a Research Programmer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library, where he serves as lead developer on the Digital Collections platform and related software services.

Brynlee Emery

Brynlee Emery is the former Graduate Assistant for Digitization Services at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where she managed quality control and ingest workflows for digitized items. She now works in corporate digital asset management in Salt Lake City.

Rachael Johns

Rachael Johns works as a Digital Imaging Specialist II at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, digitizing library materials and supporting the use and maintenance of digitization and photography tools.

Patricia Lampron

Patricia Lampron is a Metadata Services Specialist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, specializing in organizing metadata for digital collections and making these collections accessible through the Digital Collections platform.

William Schlaack

William Schlaack is the Digital Reformatting Coordinator at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library. In this role he oversees general collections and vendor-based reformatting efforts.

Angela Waarala

Angela Waarala is the Digital Collections Project Manager at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where she oversees the digitization of on-demand requests and special collections.

End Notes

[1] University of Illinois Office of the President. COVID-19 policies. University of Illinois Massmail. 2020 Mar 11 [accessed 2021 May 4]. https://massmail.illinois.edu/massmail/28768.html

[2] University of Illinois Office of the Chancellor. Illinois Massmail. 2020 Mar 20 [accessed 2021 May 4]. https://massmail.illinois.edu/massmail/1741338.html

[3] Wilkin JP. COVID-19: Libraries Closed to Users. 2020 Mar 21 [accessed 2021 May 4]. (Libnews email list). https://wordpress.library.illinois.edu/staff/wp-content/uploads/sites/24/2020/03/COVID-19_-libraries-closed-to-users-March-21.pdf

[4] University of Illinois Office of the Chancellor. Illinois Massmail. 2020 Apr 2 [accessed 2021 May 4]. https://massmail.illinois.edu/massmail/9999819.html

[5] Prom C. HathiTrust Emergency Temporary Access. 2020 Apr 1 [accessed 2021 May 4]. (Libnews email list). https://wordpress.library.illinois.edu/staff/wp-content/uploads/sites/24/2020/04/HathiTrust-Emergency-Temporary-Access.pdf

[6] University of Illinois Office of the Chancellor. Illinois Massmail. 2020 Jun 2 [accessed 2021 May 4]. https://massmail.illinois.edu/massmail/8421413.html

[7] See University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. COVID-19 Briefing Series: SHIELD – Target, Test, Tell – COVID-19. 2020 [accessed 2021 May 4]. https://covid19.illinois.edu/updates/covid-19-briefing-series-shield-target-test-tell/. To note, the university introduced a saliva-based COVID-19 testing protocol for the university community, and required regular testing (once or twice a week, depending on infection rates in the university community) for affiliates seeking entry into campus buildings.

[8] Murphy H. Back to On-Site Work Weekly Update. 2020 Aug 11 [accessed 2021 May 4]. (Libnews email list). https://wordpress.library.illinois.edu/staff/wp-content/uploads/sites/24/2020/08/Back-to-On-Site-Work_-Weekly-Update-4.pdf

[9] Hennessey CL. Customizing Alma and Primo for Home & Locker Delivery. The Code4Lib Journal. 2021 [accessed 2021 Mar 1];(50). https://journal.code4lib.org/articles/15521

[10] Hansen DR, Courtney KK. A White Paper on Controlled Digital Lending of Library Books. LawArXiv; 2018 [accessed 2021 Apr 30]. https://osf.io/7fdyr. doi:10.31228/osf.io/7fdyr

[11] For more information on the Library’s transition from Alma to Voyager, some resources are available here: Alma Training – Staff Website – U of I Library. [accessed 2021 May 5]. https://www.library.illinois.edu/staff/alma/

[12] Ex Libris. Add Link to HathiTrust. Ex Libris Developer Network. [accessed 2021 May 26]. https://developers.exlibrisgroup.com/appcenter/link-to-hathitrust/. Note: We modified the code for this add-on to include both public domain as well as in-copyright items.

[13] For an example, see https://digital.library.illinois.edu/collections/6ff64b00-072d-0130-c5bb-0019b9e633c5-2

[14] DT Heritage. DT BC100 High Resolution Book Scanning System. [accessed 2021 May 5]. https://heritage-digitaltransitions.com/dt-bc100/

[15] For more information on automating image capture using this software, view: Peterson D. DT CropControl. DT Photo. 2017 Oct 24 [accessed 2021 May 5]. https://www.photo-digitaltransitions.com/dt-cropcontrol/

[16] DT Heritage. DT Atom Entry Level Digitizer. [accessed 2021 May 5]. https://heritage-digitaltransitions.com/dt-atom-entry-level-digitizer/

[17] DT Heritage. Capture One CH Imaging Software for Cultural Heritage. [accessed 2021 May 5]. https://heritage-digitaltransitions.com/capture-one-ch/

[18] Documentation available here: Borchers H. Speedwagon Documentation. [accessed 2021 May 4]. https://www.library.illinois.edu/dccdocs/speedwagon/. Source code available here: UIUCLibrary/Speedwagon. UIUC Library; 2021 [accessed 2021 May 26]. https://github.com/UIUCLibrary/Speedwagon

[19] Universal Viewer. [accessed 2021 May 4]. https://universalviewer.io/

[20] Digital Collections at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library. [accessed 2021 May 4]. https://digital.library.illinois.edu/

[21] News Bureau. University outlines fall plans including remote instruction after fall break. [accessed 2021 May 5]. https://news.illinois.edu/view/6367/1156975278

[22] University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library. Interlibrary Loan and Document Delivery. [accessed 2021 May 5]. https://www.library.illinois.edu/interlibrary-loan/university-of-illinois-users/

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply