by Matthew E. Hunter, Devin Soper, and Sarah Stanley

Background & Need

Florida State University (FSU) Libraries’ Office of Digital Research and Scholarship (DRS) has been partnering with FSU faculty and students on the development of digital humanities projects since 2015. Through these partnerships, DRS librarians quickly identified web hosting for digital projects as an important gap in FSU’s academic computing services. For example, many of the researchers who participated in DRS’s first Project Enhancement Network and Incubator (PEN & Inc.) program in 2016 expressed web hosting needs that the Libraries were not able to meet with our IT infrastructure at the time, and that also did not meet the criteria for hosting through FSU Information Technology Services (ITS) Website Content Management System or WebDAV site hosting services. Similar needs were expressed by the faculty who participated in the Demos Project for Studies in the Data Humanities (est. 2018) and by faculty and students affiliated with the Program in Interdisciplinary Humanities’ Digital Humanities MA program. In each of these cases, faculty and students expressed a need for flexible web hosting that would enable them to easily install a variety of different content management systems, from hyper-accessible options like WordPress to more specialized options like Omeka and Scalar. They also expressed a need to have some level of control over the development and administration of these sites, including the ability to create accounts for student workers tasked with creating and publishing content on the domains as well as the ability to make updates to the content as needed. In thinking through these needs, the DRS team realized that the requested web hosting service could also help to round out existing campus infrastructure related to digital pedagogy, particularly for instructors wishing to produce web-based pedagogical materials or assignments outside of Canvas, the learning management system environment employed by FSU. Specifically, we recognized that a flexible web hosting service could provide FSU instructors and instructional support offices such as the Office of Distance Learning and the Center for the Advancement of Teaching with an additional tool to enable the exploration of innovative pedagogical frameworks (e.g., open pedagogy and public writing) and to continue to meet the needs of distance learners in new and innovative ways.

In evaluating options to meet these needs, there was no better candidate than Reclaim Hosting’s Domain of One’s Own (DoOO) service. Born out of collaborations between professors, instructional designers, and educational technologists, Reclaim Hosting is an LLC that provides flexible, scalable web hosting that is marketed primarily to the education sector. Reclaim Hosting supports one-click installation of over 100 popular content management systems, including WordPress, Drupal, Omeka, and Scalar. The DoOO service is designed specifically for academic institutions, and has been adopted by institutions across the US to meet a variety of use cases related to research and learning. Although most institutions use the DoOO service to support teaching and learning, there are also institutions that use it to support research specifically (e.g., University of Kentucky and University of South Carolina). Because the DRS team is focused predominantly on research support services, the use cases that we planned to accommodate with the service (and that we will address in this report) are mostly research-related; however, we recognize the utility of the service in meeting a variety of teaching and learning use cases, and we hope that we can eventually secure funding to better meet these needs in the coming years. DoOO implementations are typically branded to appeal to the users at an institution. At FSU Libraries, we chose the name CreateFSU to brand the service.

Figure 1. Screenshot of CreateFSU landing page.

Literature Review

Most case studies on Reclaim Hosting’s Domain of One’s Own service pertain to student-focused implementations that aim to support blended learning and advance students’ digital literacy skills (e.g., Kehoe & Goudzwaard, 2015; O’Byrne & Pytash, 2017; Taub-Pervizpour & Clarke, 2017; Haimes-Korn, Greene, & Rorabaugh, 2021). Winchester & Freeman (2021) discuss the use of DoOO to support digital scholarship, but they discuss it only in a cursory way as part of a broader suite of services. Hootman’s presentations at recent Coalition of Networked Information meetings (2020, 2022) provide the only in-depth case studies on the implementation of DoOO as a service in academic libraries. Given this relative paucity of published case studies, we believe that this case study about our implementation of DoOO at FSU Libraries fills a gap in the literature on the topic and could be especially helpful to readers of Code4Lib journal, particularly given the efficiencies that DoOO web-hosting can provide relative to the alternative of developing bespoke web-hosting services.

Scope and Use Cases

The DRS team proposed the CreateFSU service to the Libraries’ senior leadership team in November 2020 as a three-year pilot project. The service is supported primarily by two librarians from the DRS team and, as mentioned above, is intended to support a variety of use cases related to the research enterprise at FSU. CreateFSU is available to any FSU faculty members, graduate students, or undergraduate Honors students who want a web domain to host content related to their research. More specifically, we envisioned supporting the following use cases as types of projects that could fit within the CreateFSU portfolio:

- A faculty member interested in creating a digital supplement to a book that they authored, showcasing archival photos and other media that the publisher was not able to include in the print version.

- A graduate student interested in creating a digital appendix to their dissertation with datasets and exhibits that further support their argument which could not otherwise be included within the confines of the written manuscript.

- An interdisciplinary research team interested in crafting a website to showcase their team members’ expertise and collaborative projects in order to bolster their grant proposals to research funders.

- An instructor interested in expanding their pedagogical impact by creating a place for her students to build a digital exhibit where they find materials related to the course, share them with the class, and provide contextual information explaining how the materials relate to core curricular concepts.

- A faculty member interested in developing a website that stands as a digital-native research output in itself, such as an ongoing crowdsourced space to showcase pop culture references to her area of research.

- An instructor teaching a graduate course on digital rhetoric and first-year composition who would like to have a collaborative blog in which students can write and then comment on each other’s work.

- A Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (UROP) project director interested in creating a site for all of their research assistants to add to, which can survive beyond the yearly required poster, and which project alumni can reference as part of future portfolios.

- An undergraduate Honors in the Major student who would like to craft a digital project website to go along with their honors thesis project.

- A faculty member or graduate student is interested in showcasing notable publications, grants, and awards, as well as other salient information about their research agenda more generally while associating with the broader Florida State University web environment.

To keep support of the project in-scope and sustainable for the pilot period, our team originally planned to restrict the following use cases as out-of-scope:

- Departmental websites (including research centers and institutes)

- Student assignments [1]

- Websites that have any vendor/marketplace component

- Websites that have paywalls for access to content

In some cases, these limitations were implemented to clarify lines between the CreateFSU service and university ITS web hosting. In others, the restrictions were based on concerns about workload for librarians, university policy, and security. Lab websites for faculty were originally considered out-of-scope, but this restriction was relaxed after conversations with FSU’s central ITS. Members of the CreateFSU team and ITS determined that labs websites that fell into the category of official Research Centers and Institutes would be administered by ITS, but uncharted lab websites (i.e. a faculty member and their research team) would be eligible for the services offered by CreateFSU.

Implementation

After securing approval and funding for the three-year pilot from the Libraries’ senior leadership team, our first step toward implementation involved discussing the proposed pilot with FSU ITS leadership, particularly with respect to questions of IT governance and data security and privacy. ITS representatives recognized the needs that we intended to meet with the service were under-addressed. Therefore ITS was open to the Libraries undertaking the pilot project and gave their support. Data security and privacy were the principal concerns for ITS, with a close second being any institutional liability that might result from users’ mis-using the service to cause data security or breaches. However, these concerns were alleviated once we explained the nature of the use cases that we intended to support and offered to include language in the terms of service prohibiting the creation of websites that contain personally identifiable information (as defined by HIPAA and related privacy legislation). ITS also asked us to include language in the terms of service related to intellectual property, relevant university codes of conduct, and the right of the university to monitor content on the platform and remove it at its discretion. After the terms of service were approved by ITS, the next steps involved working with FSU Procurement to complete relevant software vendor checklists and review and draft an addendum to the DoOO contract to accommodate various requirements that are specific to our university.

Following this work with ITS and Procurement, the next steps involved configuring our instance of DoOO to reflect the new CreateFSU brand, the scope of the service and allowable use cases, and wider university branding guidelines. CreateFSU administrators at FSU were given administrative or root access to three main accounts: the CreateFSU WordPress, WebHost Manager (or WHM), and the client-management tool “WebHost Manager Complete Solution” – WHMCS. The CreateFSU WordPress gives administrators the ability to manage user accounts, create and modify request forms, and manage informational content on the CreateFSU website. WHM allows administrators to control storage quotas, modify available applications, and set default content for new application installations. WHMCS serves as the client management system, which allows administrators to email users, switch accounts between users, and terminate accounts when a user leaves the university. All of these systems work together seamlessly. For example, when an FSU user logs into the CreateFSU WordPress, an account is created for them in WHMCS. If they go on to create a domain, that domain is automatically available through WHM. The CreateFSU team also worked to further synchronize services by connecting support and new account request forms in the CreateFSU WordPress to our Request Tracker system for managing tickets.

We also created a handful of sandbox testing domains in order to teach ourselves how to use the various back-end, administrative systems that control the creation and configuration of domains. These testing environments also allowed our team to get better acquainted with the content management systems that we expected to be most popular with our target audiences. In the course of putting these aspects of the platform through their paces, we identified a number of technical issues that needed to be resolved before we could officially launch the service. For instance, we realized that automated emails sent from CreateFSU domains (e.g., for user account creation) were being blocked by spam protections put in place by our central ITS office, which required extensive troubleshooting with Reclaim and ITS stakeholders in order to find a resolution.

The conversations with ITS continued after the initial setup phase. There were several highly specific policies and compliance topics that were not identified during the initial implementation that needed to be resolved. For example, WordPress accounts accessible through fsu.edu domains would need to have their default login URL hidden for security purposes. The CreateFSU team needed to work with Reclaim Hosting to systematically hide these login locations. Additionally, the team needed to have conversations with ITS and University Communications about site branding and ensuring that each site was labeled as a CreateFSU site (as opposed to a University-sponsored site). These topics were not immediately apparent during the setup conversations and they necessitated ongoing communication with central university partners to create and implement solutions. Ultimately, both WordPress login configuration and CreateFSU labeling for sites were resolved through template installations, a feature provided through Reclaim Hosting’s services. We installed a WordPress instance in the CreateFSU environment and added and configured required security plugins. We also edited the footer of this WordPress instance to link out to CreateFSU. We were able to configure this WordPress instance to be the default content and configuration for all new WordPress installations through the service. This solution has satisfied the requirements of both ITS and University Communications.

Marketing

The CreateFSU service was, in large part, primarily a response to expressed need from faculty and students who had previously collaborated with DRS staff. Initial outreach for the service was therefore initially focused on notifying these individuals about the launch of the CreateFSU pilot. However, to move beyond this initial group and address the broader need for campus-wide web-hosting, it was necessary to develop a plan for targeted marketing and outreach. The first, easiest, and fastest way to advertise the new service was a series of blast-announcements in shared notification pathways such as those on the weekly internal libraries newsletters (to generally inform subject liaison librarians and others with potential contacts across the University) and in the campus-wide “important announcements” newsletter. Additionally, a press release was published and linked to on the Libraries’ homepage for several weeks. These pathways generated light but nontrivial engagement and resulted in several initial site provision requests.

Since the service is still a pilot and is also restricted in both user count and storage limit, there were no initial plans to send university-wide emails beyond the general newsletter and press releases. Beyond this, outreach needed to focus a bit more on those users who could reasonably be expected to have a pertinent use-case or would be interested in developing one based on their research or teaching area. Historically, DRS has had great success with word-of-mouth advertising of our services and programs, and we hoped to leverage that with a strategic focus on pitching the service to select departments, researchers, or communities we could rely on to advocate for the service in their own networks. With this in mind, our task in identifying who to initially reach out to was made easier by the initial scope of the CreateFSU use case prescriptions developed at the outset of the project.

Our primary audiences for an initial round of outreach were scholars with ties to DRS and the Digital Humanities research network on campus that we felt could utilize a website to showcase their work. These projects were often text-based or encoded textual scholarship that could utilize web technologies to publish and display their work. The first accounts created were for public-facing scholarship that engaged with legal and educational topics that were broadly pre-written and intended to be ported to the new service rather than written from scratch. Their quick completion also meant they would be great to have as initial examples we could then showcase to future potential users whose content was not already created (and administration who would be interested to see the impact of the new service).

After initial adoption by partners in the Colleges of Education and Law, we became interested in targeting our services to include more public-facing scholarship, and hence have focused our outreach into areas of research on campus that often engage with public writing and digital pedagogy centered on web-writing. To this end, we have focused our outreach efforts towards centralized locations on campus that specialize in instructional support, rather than bombarding individual users directly through additional mass emails. FSU’s Office of Distance Learning and our Center for the Advancement of Teaching were chief among these locations, as they are connected with faculty attempting to bring digital research tools and data literacy methods into the classroom. By partnering with these two units, we will be able to more easily reach faculty who are working on pedagogical projects that may benefit from the CreateFSU service concurrent with our efforts in fostering word-of-mouth advertising to research-focused use-cases.

By far, the most impactful form of marketing and outreach for the service was a digital project incubator program that provided several forms of dedicated hands-on support from CreateFSU staff. In its current iteration, the program is run by the Digital Scholarship and Digital Humanities librarians, who also serve as the primary administrators of the CreateFSU service. This incubator program, dubbed the “Project Enhancement Network and Incubator” (backronymed from the punny “PEN & Inc” abbreviation) provided participants dedicated consultation time, account provision in the CreateFSU service, and a moderate financial incentive. The incubator’s target audience was faculty and students interested in generating scholarship utilizing digital methods or work intended to be shared primarily through digital publication, with the understanding that they would be willing to serve as beta-testers for the hosting service as we worked out kinks. The PEN & Inc Program has been run twice with CreateFSU as its foundation. As a chief win, the incubator program allowed the Libraries to garner interest in the service broadly through departmental communications, two recognition events, and through the advertisement of participants’ sites. Beyond this, it provided an opportunity to refine policies and workflows and “load test” our own capacity for customized support with a group of invested and motivated researchers. The first cohort had eight applicants and eight participants. The program drastically increased in popularity for the second iteration, with 26 applicants and 15 participants. This spike in interest demonstrates the need for web hosting services and support on campus.

Partially in response to the visibility the incubator program brought to the service, our team was able to make inroads with new departments on campus that had not previously shown much interest in digital scholarship or library publishing work. One in particular was the undergraduate honors college, which is now exploring digital portfolio capabilities for undergraduates using the service.

Usage

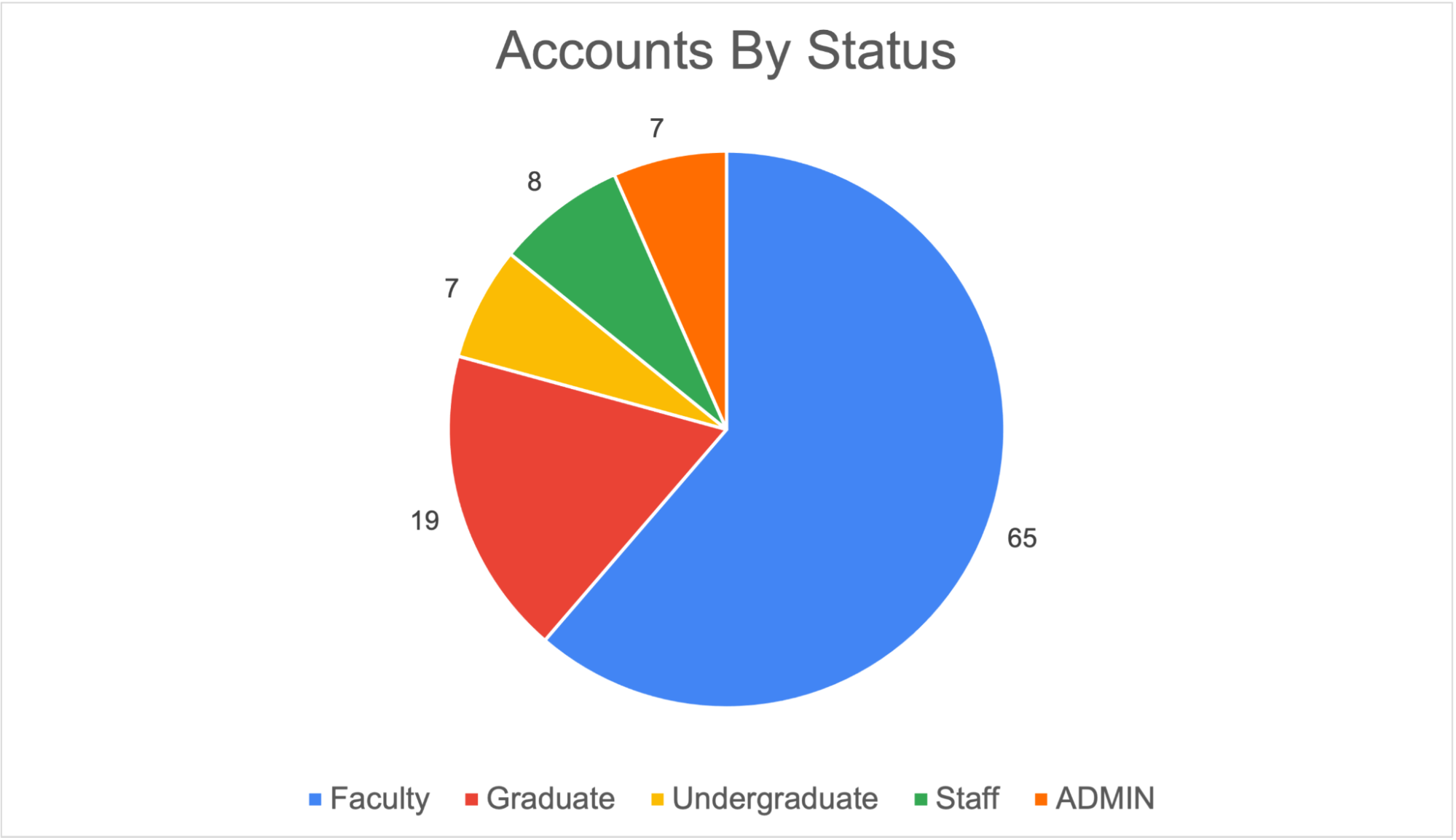

There are currently 106 total domains across 99 active users. “Active users” are defined here as users who have access to one or more domains. Of these users, a majority are faculty at the university. We also have several graduate students and undergraduate honors in the major students participating in the program. Our hope is to expand the number of users in the student category (especially those who may want a web presence for theses and dissertation projects). Accounts labeled “ADMIN” are CreateFSU accounts run by librarians to manage CreateFSU systems, test out functionality and features, and promote CreateFSU-related programming.

Figure 2. Count of users by role at FSU.

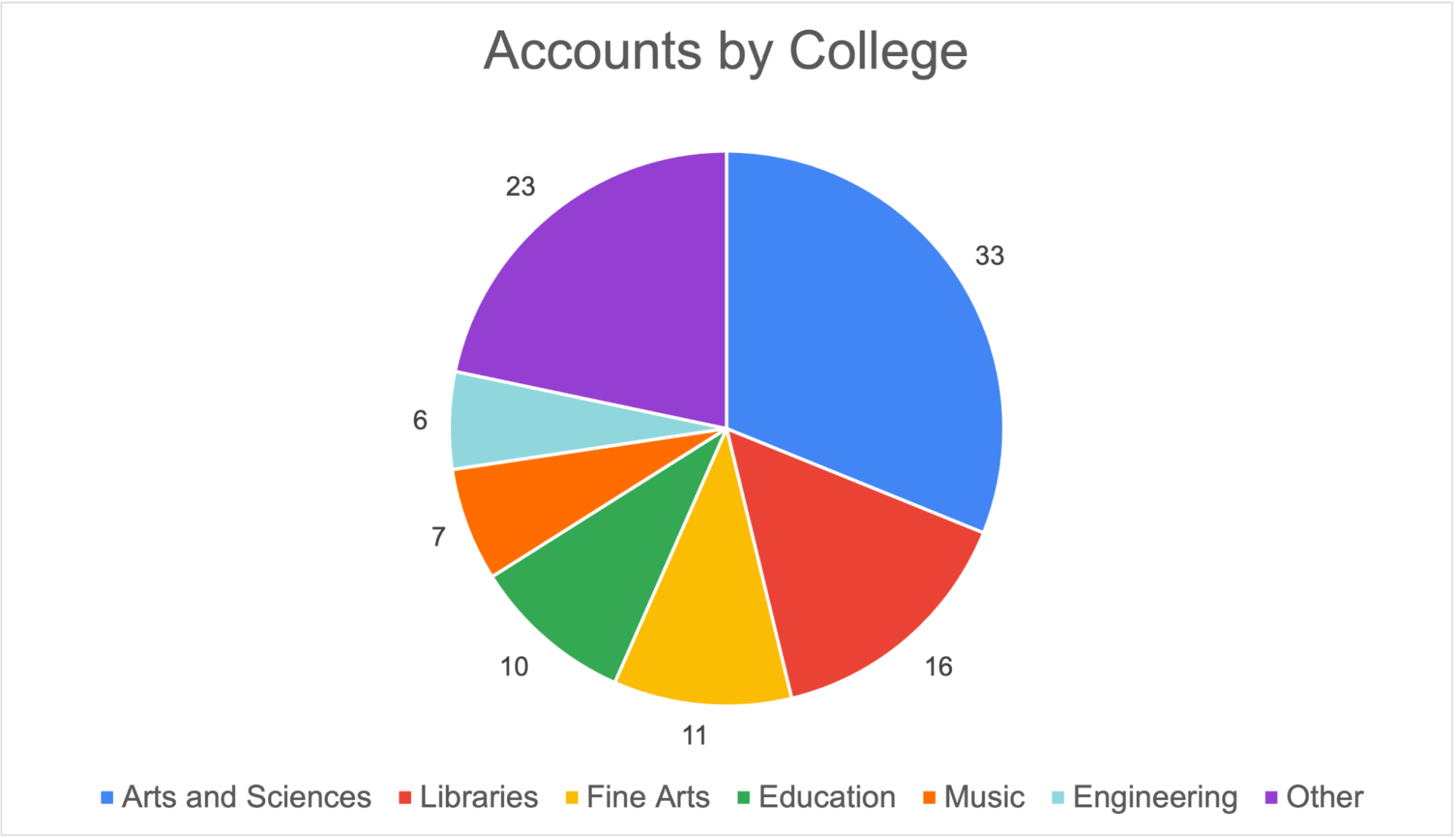

The breakdown of users by college shows a more even distribution compared to the users by role. A majority of users are from the College of Arts and Sciences (the largest college at FSU) and the University Libraries, but there is also representation from the College of Fine Arts, College of Music, and College of Education. The remaining users (listed as “other”) are from departments and colleges including the College of Human Sciences, College of Law, and other administrative units of the University.

Figure 3. Count of users by college.

The most popular content management system (CMS) used by the CreateFSU community is far and away WordPress, with 83 total installations. Omeka and Omeka S taken together comprise 13 total installations. Scalar has 6 installations across CreateFSU, and there are four other miscellaneous application installations.

During the pilot phase of this project, each account is provided an initial 1GB of storage, with the ability to increase this storage for select power-users upon request and at the discretion of our team. At present, accounts are averaging about 423MBs of disk usage, with ten accounts exceeding 1GB of space. About 22% of accounts (23 total) are utilizing under 100MBs of space. In cases where there is low space usage, it usually indicates that the user has not begun building the site beyond perhaps installing a content management system. We had a high number of new account requests (16 in total) at the beginning of our academic year’s fall semester (late August and early September) when these most recent statistics were pulled, so we anticipate that the frequency of low-usage accounts will decrease as these most recent users begin working on their sites in earnest throughout the year.

In addition to active users who are currently building sites, 381 members of the university community have logged on to the CreateFSU site to learn more about the service. As an account is generated by all signed-in FSU community users regardless of intent, we are uncertain if these users originally intended to apply for an account and were unsure of how to proceed or if they just logged in out of curiosity about the service. One of our strategies for increasing usage will be to reach out to these users and remind them about the service and how to use it.

Impact

At the start of this project, we identified several quantitative and qualitative measures to evaluate the impact of the service, with a primary interest being to understand how the service was successfully meeting the needs of our campus partners. One of the reasons for demonstrating researcher uptake was to demonstrate the value of continuing the service to administration. Many of the quantitative measures – the number of domains, number and breakdown of content management systems installed, number of pages created on each domain, number of user accounts, and usage statistics for completed websites, etc. provide a snapshot of awareness of the service across campus and have helped us to understand unmet needs across campus over the past few years. Data demonstrating these metrics track with previous anecdotal feedback from collaborators about needing easy-to-use web hosting that originally spurred the launch of the hosting service in the first place.

Since launching the program in 2021, we have found that the more effective measures in demonstrating need and success, however, have been not the quantitative counts of accounts or pages, but rather qualitative feedback received from users of the service which explain the benefit of the libraries’ provision of easy-to-use web-hosting for the benefit of their research endeavors more broadly. As there are no other humanities computing services on campus, and the only other web-hosting provided by central university IT services requires web editing software such as Dreamweaver (and the knowledge and time to manage file uploads within that service), many users have reported liking the ease of use of our service in communicating about their research to new users. This is particularly the case when dealing with users that want to provide a simple web presence for a much larger and more complex research project. As with many R1 institutions, FSU is interested in strategically expanding research accomplishment across the university, and our service seems to offer a new way of connecting with public audiences (helpful for “broader impacts” in many grant applications) and to grow the broad awareness of ongoing projects on campus.

Testimonials from many of the researchers who participated in our incubator program illustrate how the service has impacted their work and enabled them to accomplish goals that would have been difficult to attain without it. For instance, a participant in a CreateFSU-focused digital project incubator hosted by DRS remarked that the hosting service was “essential to the next phase” of a “longstanding digital project” which compiled social media and digital-native content. Their companion website, digital exhibit, and web-publication which CreateFSU served to host were paramount to the continued success of the decade-long project. In this case, the CreateFSU service filled a gap in the researcher’s scholarly support needs and allowed for centering FSU’s role in a well-respected cross-institutional digital project. Another researcher was able to extend the reach and scope of a physical exhibit that he created in collaboration with FSU’s Museum of Fine Arts by using the CreateFSU service to lay the groundwork for a companion digital exhibition page that has a national reach. This researcher also highlighted how CreateFSU’s support infrastructure and mechanisms for guidance (through tickets, built-in support documentation, and community) made the project possible for himself and a team of new undergraduate and graduate collaborators in a way that was otherwise not supported by other mechanisms at our institution. These support systems do not always exist when faculty create sites on their own, and providing them institutionally through CreateFSU helps ensure that projects are feasible for users new to web publishing.

Challenges & Opportunities

One of the first challenges that we encountered during this process was the issues of funding. Although the base cost of a DoOO contract ($6,000 at time of writing) is very reasonable compared to the cost of many of the e-resources packages that libraries routinely license, the idea of libraries paying a vendor to provide web hosting as a service was new to most of our colleagues and was originally met with some trepidation. Given that our Libraries – like most academic libraries – have been experiencing flat or declining budgets for decades, it was understandable that advocating for the diversion of limited resources away from existing priorities in order to try something new would not be immediately popular. However, we have thankfully been able to document a long history of expressed need on campus which made the case for funding stronger and ultimately successful. Even more than that, the rapid success of the program was such that, after the initial launch, positive user feedback and steady demand helped the team to successfully secure an additional 3-year renewal after the initial 3-year trial period.

Funding was just the first of many challenges, however. The next-largest challenge was related to staffing capacity. There is an immense amount of staff time required to implement and launch a service like this, including not just all of the work outlined above, but also the ongoing administration and maintenance. This entails responding to domain requests, onboard users into the system, ensuring that they have access to training and support documentation relevant to their chosen content management systems, and helping them troubleshoot issues that invariably come up and require outside assistance. In our case, we were fortunate to have three librarians who were able to devote a portion of their time to getting the service up and running – two of whom are responsible for ongoing management of the service and have been able to handle the demand to date. However, covering this new suite of service offerings meant pulling capacity from their other duties – something that had to be negotiated with a wide variety of stakeholders including academic departments and internal committees. We were also fortunate that the two librarians tasked with ongoing management of the service already possessed advanced technical skills that put them in a good position to learn about the intricacies of the platform and troubleshoot issues as they arose. That said, should the service become significantly more popular than it is currently – which is likely if we expand the allowable use cases – it may outstrip our current capacity.

The time commitment required of users to claim and populate their domains with content is another notable challenge. In the case of faculty, this challenge is well documented in the literature on labor in the digital humanities (Vinopal and McCormick 2013). Faculty across the disciplines are faced with a multitude of competing priorities that demand their time and attention, and, as a result, it is typically very difficult for these users to find additional time to take on work related to digital content creation. This problem is exacerbated by the nature of reward systems in higher education, and particularly guidelines and expectations around review, promotion, and tenure, which tend to value work that produces more traditional research outputs such as journal articles, books, and grant proposals. The incubator program discussed above is one example of a strategy that can help to mitigate this challenge by providing faculty with structured support and some measure of recognition for their efforts, but the challenge remains a redoubtable one for most faculty. Time commitment is also a challenge for students, particularly in cases where their work on a domain and related content is not integrated with curricular or academic program requirements. In such cases, students need to carve extra time out of their already busy schedules to devote to crafting additional content, and this can be exceedingly difficult for students who are already enrolled in a large number of courses and/or have significant competing demands on their time related to employment and familial duties. And though this set of challenges is real and significant, it most directly impacts our provision of this service through the fact that our success or failure can be seen in the number and quality of sites published using the service. When that metric is out of library control, and to an extent even beyond the personal control of our service partners (being as it is a structural and systemic issue), determining success based on content creation is a challenge.

One promising opportunity for growth that manages to address some of the challenges above is the provision of web-hosting for curricular student projects. There are several units on campus that either currently use or are exploring the use of eportfolios for undergraduate work. We believe that CreateFSU could be useful for some or all of these eportfolio use cases. Eportfolios are a particularly good fit for the service because they are relatively short-term projects based on a relatively small number of individual works comprising a thematically recognizable thematic project. The students are also extrinsically motivated to complete these projects, which helps drive completion. However, the current size of these programs and the large number of individual students that participate currently prohibit them from being included in CreateFSU based on our current level of support. One unit alone (such as the Editing, Writing, and Media program housed in the Department of English) could single handedly fill the 500 account limit within two years. In order to manage resources such as this account limit, we need to find ways of testing eportfolio use-cases at a smaller scale without excluding other students in the cohort. Testing like this is necessary for determining if CreateFSU would serve this need at scale, but remains a promising glimpse at what the future of the service could look like at expanded levels.

Conclusion and Looking Ahead

Although the first two years of the CreateFSU pilot was successful, there is much work that remains to be done. Specifically, our team would like to do more to promote the service to the FSU community and enlist the support of campus partners whose missions could benefit from broader use of the service. One ongoing goal that we have is to build more robust support resources for CreateFSU users. We are currently in the process of enhancing support documentation and resources to better answer users’ needs and questions without relying on one-on-one consultation time with our team. We are also exploring one-to-many support options such as workshops and group training sessions, templates for popular use cases, and short video tutorials that guide users through the process of installing applications on their domains and using their chosen applications to achieve their goals. Based on interest in and use of the service thus far, we would also like to more sustainably broaden the allowable use cases for the service to include lab websites, funded projects, and e-portfolios, to better meet needs across campus. We believe that allowing these use cases would significantly increase engagement with the service and, with a bit of conscientious planning, are confident that we have the capacity to support the additional projects. Our team is also seeking additional resources to support the service including funding from campus partners. This additional support will be extremely useful in the future if we wish to accommodate the new use cases mentioned above, providing not only some overhead for supporting the labor demands, but also financially allowing us to expand the service beyond the 500 accounts that are included in the initial rollout. Marketing is another ongoing priority for a service like this which we would like to expand. Like all universities, FSU welcomes well over a hundred new academic staff and thousands of new students each year, and the only way to inform these new members of our community about the service is through ongoing, targeted marketing and promotion. Finally, our team is developing a survey to gauge overall satisfaction with the service, the technical support that we provide, and the selection of applications available through the platform. We will also use this survey to assess how many outputs are finished vs. unfinished, active vs. inactive, and faculty-created vs. student-created, as well as the distribution of content management systems selected by users. Although we still have many goals to accomplish, we believe that the first two years of this project have been a success and have made a positive impact in the lives of many creators at our university.

References

Haimes-Korn K, Greene J, Rorabaugh P. 2022. Cultivating a Grassroots Approach to Digital Literacies via Domain of One’s Own. In: Multimodal Composition Faculty Development Programs and Institutional Change. [place unknown]: Routledge; p. 241–258.

Hootman J. 2020. CreateUK: Opportunities for Digital Pedagogy, Projects, and Collaborative Infrastructure [Internet]. In: [place unknown]; [accessed 2023 Sep 11]. https://works.bepress.com/jlhootman/27/

Hootman J. 2022. CreateUK: A Review and Recommendations for Growing and Enhancing Campus Collaborations [Internet]. In: [place unknown]; [accessed 2023 Sep 11]. https://works.bepress.com/jlhootman/34/

Kehoe A, Goudzwaard M. 2015. ePortfolios, Badges, and the Whole Digital Self: How Evidence-Based Learning Pedagogies and Technologies Can Support Integrative Learning and Identity Development. Theory Into Practice. 54(4):343–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2015.1077628

O’Byrne WI, Pytash KE. 2017. Becoming Literate Digitally in a Digitally Literate Environment of Their Own. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. 60(5):499–504. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.595

Taub-Pervizpour L, Clarke T. 2017. Cultivating Open Blended Learning with Domain of One’s Own [Internet]. [accessed 2023 Jun 14]. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/blended_learning/2017/2017/10

Vinopal J, McCormick M. 2013. Supporting Digital Scholarship in Research Libraries: Scalability and Sustainability. JOURNAL OF LIBRARY ADMINISTRATION. 53(1):27–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2013.756689

Winchester S, Freeman A, Boyd K. 2021. From the Ground Up: Building a Digital Scholarship Program at the University of South Carolina. South Carolina Libraries [Internet]. 5(1). https://doi.org/10.51221/suc.scl.2021.5.1.5

Notes

[1] Instructors may create one domain per course and enable their students to register for author accounts on that domain. This use case is suited to assignments for which students engage in public writing (e.g., course blog), collaborative curation projects (e.g., Omeka projects), or other digital pedagogy assignments.

About the Authors

Matthew E. Hunter (ORCID: 0000-0003-4858-6947) is the Digital Scholarship Librarian at Florida State University Libraries.

Devin Soper (ORCID: 0000-0002-2667-4594) is the Director of the Office of Digital Research & Scholarship at Florida State University Libraries.

Sarah Stanley (ORCID: 0000-0001-6089-3910) is the former Digital Humanities Librarian at Florida State University. She is currently pursuing an Master of Arts in Teaching at Moravian University.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply