by Tyler Mobley and Heather Gilbert

Background and Existing Infrastructure

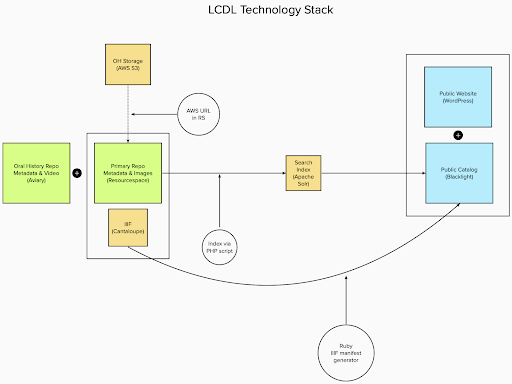

The Lowcountry Digital Library (LCDL) is a multi-institutional cooperative digital library that currently hosts several hundred collections consisting of almost 150,000 digitized images, objects, pages, and recordings of primary source materials and their associated metadata. LCDL is built around the open-source ResourceSpace digital asset management system that serves as our central repository for metadata records and presentation-quality digital files ranging from still images to audio files and PDFs. To bring these collections to the public, we created a custom plugin that indexes records in the repository to Apache Solr, a Java-based search platform. Indexed records are then available for search and discovery via Blacklight, LCDL’s primary catalog. Blacklight is a Ruby-based search and discovery platform that provides a graphical interface for interacting with data in the Solr index. It provides full-text and faceted searching of all our materials, and the College of Charleston Libraries has relied on it for nearly a decade across both LCDL and the South Carolina Digital Library (SCDL), a provider hub for the Digital Public Library of America.

Figure 1. Current LCDL technology infrastructure diagram.

LCDL currently hosts over 600 oral histories in audio and video formats. Our oral history collections have grown at a steady trickle over time, though we have noticed a substantial increase in interest in recent years from partners both within the college and local community thanks to the sudden ubiquity of smartphones and accessible audio visual options. As LCDL is focused on the collecting of historic cultural heritage materials related to the Lowcountry region of South Carolina, our hosted oral histories have naturally hewed to this subject area. However, we have increasingly been approached with oral histories covering topics and time periods that don’t necessarily fit the stated mission of LCDL.

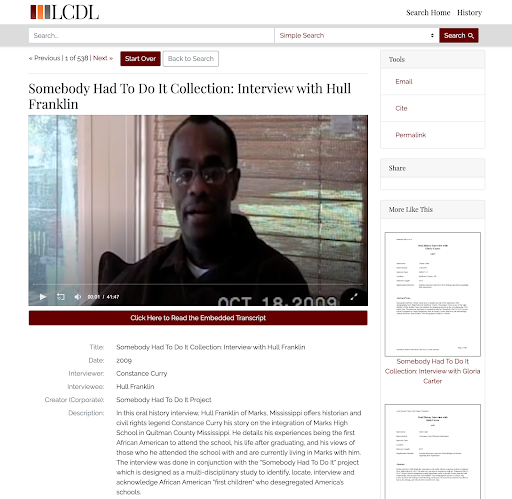

Historically, oral histories in LCDL have been loaded to ResourceSpace in bulk as metadata and digital files. However, rather than serving these large files directly from ResourceSpace, we host copies of oral history files in Amazon S3 storage and serve them for streaming with Amazon CloudFront, a content delivery network (CDN) better suited for flexible streaming to browsers. The metadata records loaded to ResourceSpace contain a field referencing the file’s address on CloudFront. When indexed, that metadata field is served to Blacklight to fill HTML embed code to embed the file on item pages for viewing. You can see an example of how that final item looks below. While this system allowed us to get oral histories online in a way that was adequately usable, it lacked in features and functionality.

Figure 2. Existing LCDL oral history user interface. Selecting the “Click Here to Read the Embedded Transcript.”

Assessing Our Options

We began evaluating our options for a better oral history public interface in 2021. We knew that we wanted to provide a more sophisticated experience for our patrons accessing oral histories. As mentioned above, LCDL employed an embedded PDF viewer for patrons to view transcripts while listening to an oral history, however we wanted the ability to offer value added features such as auto-scrolling of time-stamped transcripts and subject indexing. As we considered our options, deciding factors also included sustainability, personnel support requirements, and pricing. The College of Charleston Libraries has a history of working on a shoestring budget, but for sustainability purposes has been actively seeking out hosted solutions to specific digital projects with an effort to increase scalability and project longevity. We also knew from previous migrations that for sustainability purposes, any new platform had to have the ability to import AND export our content accurately and efficiently. Additionally, we knew that adding advanced features to our oral history platform couldn’t require the need to hire additional staff, we had to work within our existing personnel infrastructure. Finally, we knew the solution had to be cost effective. Requesting recurring funding wasn’t out of the question, but the cost to benefit ratio had to be well supported.

We assessed several different options including the University of Kentucky’s Oral History Metadata Synchronizer package known as OHMS (including incorporating OHMS into our existing digital library infrastructure), Alma Digital (College of Charleston Libraries migrated to Alma in 2020), DSpace (which at the time was the foundation for our existing albeit underused institutional repository), and Aviary, which is a collaboration between AVP and Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. OHMS offered the most options for developing a sophisticated oral history viewing interface. However, it would require self hosting, increasing our already hefty server footprint, advanced retraining of existing staff and, in all likelihood, the addition of personnel to support the extra work of file preparation, assuming we really wanted to take advantage of all OHMS had to offer. During our assessment, the barrier to sustainability was high enough that we didn’t need to assess this platform further using our other criteria. It was decided that this option was perhaps too sophisticated for both our needs and our capacity for support.

Alma Digital was an appealing option as we had just fully migrated to Alma the year prior (2020), however we found the Ex Libris-provided documentation on Alma Digital lacking in specificity as to what the repository could actually do and after significant testing on our part we encountered problems having Alma Digital support our advanced MODS metadata schema. While Alma Digital could support both audio and video file formats, we found the user interface to be too simplistic for our needs. Alma Digital support documents indicated some import and export options, but with the platform’s simplicity, it wasn’t worth pursuing during our assessment. Alma Digital just didn’t suit our needs. Similarly, we determined that DSpace was an unsuitable option. Like Alma Digital, DSpace has the ability to support audio and video file formats in their repository, but the interface was also lacking. Dspace has robust import and export tools, but, ultimately that wasn’t enough to make it a good match for our needs. We decided that both Alma Digital and DSpace didn’t provide any advantages over the existing LCDL display of oral histories.

Aviary was our last option to evaluate, and we were pleasantly surprised by what we found. Aviary offered the advanced user interface options we were looking for, including auto scrolling of time-stamped transcripts and the ability to add custom indexing, while also providing a user-friendly back-end experience. This made it easier for us to use existing staff who were more experienced with using a GUI as opposed to a terminal or code-based command structure. Aviary was a hosted solution, so we wouldn’t be adding yet another digital project to our server support portfolio, and considering the modest size of our collection, it was relatively affordable. Finally, Aviary offered us a lot of flexibility. We could batch load collections or single load items, we could use some advanced features or use none of them without losing the level of interface we already provided in LCDL, we found we could embed Aviary objects within our existing digital library for seamless discovery, and Aviary offered a variety of permission and access levels that could support a wide range of use-case scenarios for digital collection access. Furthermore, Aviary provides a flexible API for interacting with resources and media files in the system. While the user interface provides multiple means of importing and exporting loaded oral history materials, the availability of an API to programmatically handle import and export in batches eased concerns about the possibility of future platform migrations and accidentally trapping our data in a closed system.

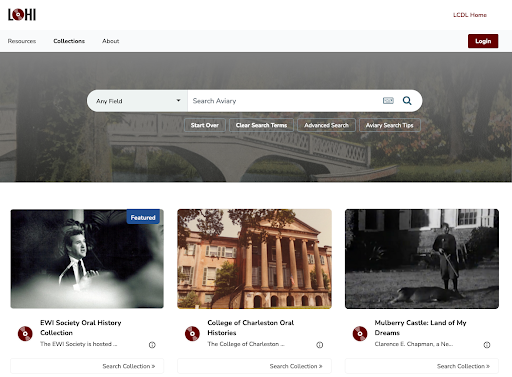

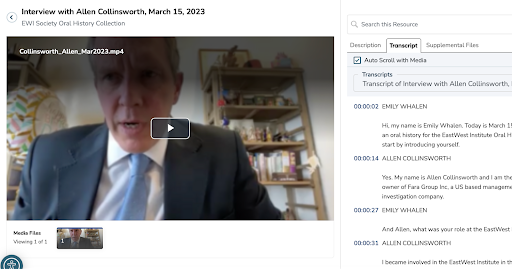

Aviary’s flexibility has helped us prepare to serve a growing need for campus supported oral history projects alongside our legacy cultural heritage material. With Aviary, new collections of oral histories not within the scope of LCDL can be loaded and presented through a styled search and discovery interface on Aviary’s own platform. Each institution’s collections are discoverable through a custom site to which a custom domain can be applied (in our case, https://lcdl.aviaryplatform.com), and the entire library of items hosted across all subscribers is also searchable as a federated catalog. Our mission with Aviary is to serve a new and growing audience in oral histories at our institution while also enriching the production and presentation of our existing collection of cultural heritage oral histories in LCDL.

Figure 3. The Aviary platform interface provides discovery for all of our a/v collections whether they are outside the scope of LCDL (EWI Society Oral History Collection) or within the scope of LCDL (College of Charleston Oral Histories).

Configuration and Batch Loading

Aviary, as stated, is its own hosted platform, providing search and discovery for users alongside collection browsing functionality. In adopting Aviary, we realized we would have to reconsider our workflows for oral histories at both a procedural and technical level. This was something of a quandary. Should we now only load items straight to Aviary instead of our backup-redundant repository? Should we remove oral histories from LCDL’s primary catalog and direct users to Aviary instead?

For the purposes of item loading and record creation, we decided on a two-fold approach. Metadata for LCDL collections would continue to be loaded to our ResourceSpace repository as before. These collections would not be indexed to the catalog from ResourceSpace, but they would remain together in a central location with other LCDL materials to ensure continuity in case of future platform migrations. These collections would then be additionally loaded to Aviary via the system’s import job functionality.

The batch-loading system employed by Aviary allows an administrator to load CSV files for metadata, media files, transcripts, and even indexes as a single job, and then Aviary ties those components together to create complete resources. In this process, an oral history collection might be loaded with any number of rows representing individual resources in a ‘resources.csv’ file including a column for a unique identifier. The companion ‘media.csv’ and ‘transcripts.csv,’ representing AV-related files and transcript files respectively, would hook on that primary key and create the relationships on the Aviary back-end.

In order to import just over 600 legacy oral histories into Aviary, we ran metadata exports of records per collection from our Apache Solr index to CSV format. This could have also been done via ResourceSpace’s metadata export process, but our Solr index more cleanly outputs extra data used for presentation like presentation filenames, transcript details, etc. This process provided us with a CSV file for each oral history collection containing descriptive metadata for all records in that collection, one record per row. Next, we pulled the CloudFront URL from this CSV into a separate ‘media’ CSV file, again formatted one item per row. This file also included columns for both the record’s primary identifier and a new unique identifier for the media file. Finally, in a third ‘transcripts’ CSV file, we broke out the file path to each transcript per record as one record per row. This file additionally included a column referencing the media file’s unique identifier to ensure that they were associated upon load. These three CSV files were then loaded in-browser to the Aviary platform alongside a zip file of the referenced transcript files. Once all necessary files were loaded, and the import job was assigned to a collection, the job ran in the background and records were added to Aviary.

While the details above might sound a little daunting, the process for our workflow ultimately involved taking one CSV file, splitting it into three, and adding some additional administrative fields before uploading them all at once. Since we usually only receive small batches of new oral histories at a time, our typical process going forward will most likely center around single item loading directly into Aviary via traditional form-based data entry. However, it’s worth keeping in mind that for platform migrations or unusually large loads of oral histories, Aviary’s import job functionality works effectively.

In the event of future batch loads, we have since taken advantage of ResourceSpace’s plugin functionality and written a plugin that produces an Aviary-compliant ‘resource’ CSV file for use with the import job process. This should reduce some data manipulation steps and allow our staff, at least at a metadata level, to only worry about the initial metadata creation and load process.

With Aviary’s import functionality, we were able to load our bulk of legacy oral histories to Aviary in about 12 total ‘jobs.’ Most of these records, though successfully loaded, were not immediately made public as we then had to work through metadata remediation on the legacy metadata and transcripts associated with these oral histories. Further, each collection in Aviary had to be configured for appropriate display of our preferred metadata fields.

Content Migration

Because of Aviary’s enhanced feature set, we wanted to not only batch load new collections, but migrate existing LCDL collections into the new platform. This would allow our legacy oral history collections to benefit from these features if project partners wanted to review these items and add augmented metadata such as time stamping and/or subject indices. However, as with most migrations, this required remediation efforts. While we were able to use batch loading to easily migrate all of our existing oral history collections into Aviary, the content was not adequately formatted for public display. We determined that, to get the most out of our Aviary instance, we would need to manually configure metadata mapping for each Aviary collection, reformat transcripts to meet Aviary’s transcript requirements, load PDF transcripts in Aviary’s “supplemental file” field for researchers to have downloadable access, and finally create subject indices (as time and budget allowed) for recordings that would best benefit from this feature.

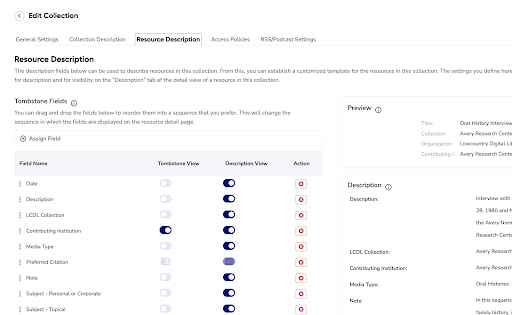

Aviary comes standard with a robust set of Dublin Core metadata elements but it also allows for broad metadata field creation and customization. LCDL collections are described using the MODS metadata schema, so batch importing the collections also imported our metadata elements as custom fields. This worked well for us as it meant that we didn’t have to do much metadata rectification pre or post migration. However, as the end goal for our LCDL Aviary destined collections was reintegration within the LCDL platform, it was important for us to mirror the display order of the metadata elements between LCDL and Aviary. Aviary allows for this level of customization at the collection level on the Resource Description menu but there is no way to customize metadata field order at the instance level (as far as we could determine at the time of this writing). This is unfortunate for a project of this nature, as our display order is uniform across collections. While the Resource Description page is easy to use with a drag and drop interface, it must be configured for each collection to adequately reflect the metadata display order we desire. While this isn’t overly time consuming, for as granular a product as Aviary is, it feels like an oversight to not have the ability to set display preferences at the instance level. However, Aviary is being very actively developed, with each update providing major improvements, so it’s quite possible that this may be available in the future.

Figure 4. Aviary allows for granular customization of metadata fields and display at the collection level.

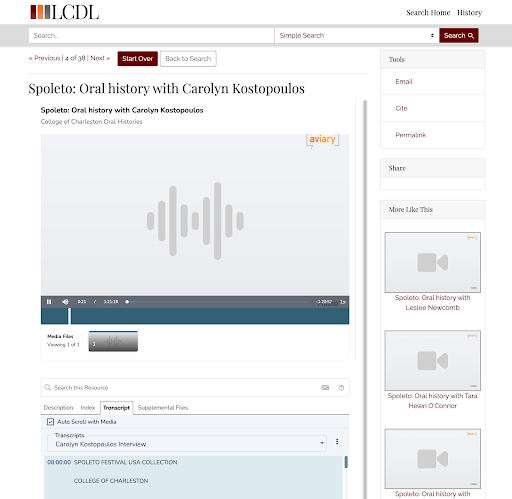

Unfortunately, transcript migration is proving to be the most challenging part of our rectification project. Our legacy oral history collections only required the submission of PDF transcripts. Aviary utilizes .doc, .docx, or .txt transcripts for their transcript display. This is requiring us to convert PDFs to Word documents and clean up formatting issues to conform with Aviary import preferences. As with all products, there are quirks. If a transcript contains any text that is in HH:MM:SS or HH:MM format, even if it is within a sentence, Aviary interprets this data as a timestamp and will link the sentence, inappropriately, to the time indicated. This is easy enough to correct within transcripts, however, we’ve also noticed that Aviary will treat any colon used within a sentence, even without numerical context, as a 00:00 timestamp and will wrongly link the sentence and/or paragraph. This is something that we are addressing with future projects in a transcription style guide, however it still is adding time to our rectification process of legacy materials. Some of our older oral history collections had their transcript text formatted into tables, therefore stripping out this formatting in the Word document is necessary but time consuming. Ultimately, we think the time involved will be worth it as we’ve developed robust find and replace practices that help with some of these formatting challenges. Additionally, we still get to make good use out of our original PDF transcripts. Aviary provides a “Supplemental File” field for every record. We’ve found that we can load the PDF transcript in that field and allow download access. This way our patrons get the best of both worlds – the recordings can be listened to/watched with auto-scrolling enabled (assuming time stamps are in place) and they can download a human-readable transcript for later research use.

Figure 5. The Aviary public user interface provides a tabbed viewing experience. The description tab displays item level metadata, the transcript tab allows for auto-scrolling of time stamped transcripts as well as multiple transcript selection support, and the supplemental files tab allows for downloadable PDF transcripts (in addition to other file formats).

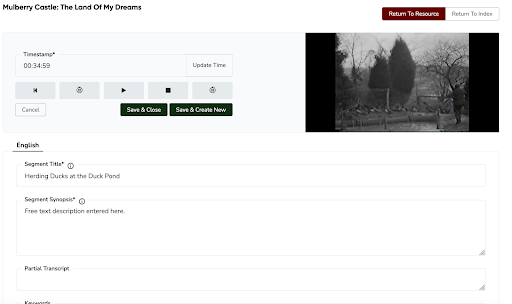

Subject indexing is one of the areas that excited us most about Aviary, but in the short term it is the feature we have used least. We plan on leveraging this more post-migration as an optional, value-added feature that can be used to augment existing metadata or possibly be leveraged as an experiential learning opportunity within faculty/student partnership projects. Aviary allows for batch importing of subject indices, but also provides a very easy to use back-end interface for one-off index creation. From the Aviary back-end, any recording can be reviewed, and a subject index added using a set of simple forms. The index can be as complex as including the relevant portion of a transcript or as simple as adding a title and very brief description. Indices can also include keywords and subject headings, which are searchable within both the resource and the overall platform, GPS data, and hyperlinks. Subject indexing is an area which we have just started to experiment with. We’ve created some recommendations for indexing for our partners both to ensure best practices are being followed and to moderate expectations and requirements of staff time. In the future, we hope that this feature may lend itself to faculty/student collaborations, where a faculty member might want to assign a recording to a student and that student can then review and suggest appropriate subject indexing. In early conversations, faculty have shown interest in this potential.

Figure 6. In addition to batch loading of subject indices, Aviary also provides a friendly user interface for recording review and index creation. We anticipate being able to leverage this to create more interactive experiential learning opportunities for students on future projects.

Integration with Existing Platform

In terms of presentation and discovery, we quickly decided that removing oral histories from the LCDL catalog would hinder search and discovery and undermine our promise to our partners that the items they had submitted to us would be in LCDL. We would need to find a solution that maintained a search and discovery experience that our partners and audience had come to expect while doing our best to integrate the benefits gained from leveraging Aviary. To that end, we began work on integrating Aviary items into our primary catalog by indexing Aviary data into Apache Solr with the Aviary API.

Aviary’s API was an attractive feature for us when we were reviewing the platform. It provides well-documented RESTful interaction methods for loaded resources and collections. This allowed us to leverage the API via a script in PHP. The script is fairly simple. It accepts a passed-in CSV file of resource identifiers that correspond to items in Aviary. The script then authenticates against the Aviary API, iterates over each resource, and builds and commits a Solr document for each resource to our Apache Solr index. In iterating over each resource in Aviary, we do some modifications to records. First, since Aviary’s API outputs metadata field names in their proper display format, the script crosswalks those field names to their Solr counterparts. For instance, ‘Date Digital’ translates to ‘datedigital’ or ‘Contributing Institution’ to ‘contribinst.’ Further, we inject new fields into the record for easier flagging and control in Blacklight. For example, we inject a custom placeholder image URL for a thumbnail for catalog display, and we also add an ‘is-aviary’ field as a simple flag to check when loading image viewers on oral history item pages. In our current transitory period of launch and migration, the flag allows the catalog pages to quickly slot in either legacy viewer code for CloudFront URLs or a new embed snippet from Aviary depending on the value. Through this script, we can serve the primary LCDL catalog with results mixed from both our central repository and Aviary in a single search.

While integrating two data sources into a single index was straightforward, we had philosophical discussions about how to handle the item display of these mixed results. Initially, we considered making Aviary items in the catalog open a new tab to show the Aviary resource page in full. Of course, that presented the issue where we would be jettisoning users from the site and their own search patterns without a clean way to get them back into the catalog. Ultimately, we opted to leverage Aviary’s embedding feature directly into our item display.

One of the big strengths of Aviary that drew us to the platform was the richness of its viewing experience. As discussed earlier, Aviary provides auto-scrolling transcript functionality, indexed timestamps, and other features that we do not have the time or capability to incorporate directly into LCDL ourselves. Instead, legacy oral histories simply provided an audio/video player and an embedded PDF of a transcript alongside each other, previously shown in an example image above.

To get the full benefit of our investment in Aviary, we decided to use Aviary’s embed functions on item show pages. The embed functionality provides a duplication of the full viewer as seen on Aviary, and allows users to follow along with transcripts live, navigate an oral history via timestamps, and more. This functionality does rely on an iframe currently, but thanks to the fact that all our Solr-indexed metadata is still included farther down the page as usual, we do not lose any helpful SEO or readability on the record. An example of an Aviary embed on the LCDL catalog can be seen below.

Figure 7. Aviary hosted oral history viewed within the LCDL platform. Note that transcript auto-scrolling is an option as are subject indices and supplemental files.

Workflows for New Oral History Projects

Oral history was identified as a growing need on the College of Charleston campus several years ago, however many potential oral history projects did not fit the criteria of the Lowcountry Digital Library. As discussed above, using Aviary has provided us with significantly more options for supporting campus oral history projects as we can now provide a platform and federated search for all oral histories while still only integrating oral histories into LCDL that meet that platform’s curation criteria.

We’ve had early success working with academic faculty outside the library, using simple strategies to manage workflows while still collecting the data needed to upload and make their recordings accessible. These strategies include early intervention regarding project development, copyright, and informed consent, campus sponsored digital file storage, and data collection using simple online forms.

Setting expectations early with faculty regarding project development and the level of informed consent needed in oral history projects was vital to our early success. Prior to this strategy, the library was being approached with completed “oral history” projects with the incorrect expectations that:

- We would accept any project into our Special Collections holdings and

- We would rapidly provide anything from online access to a custom website, digital catalog, and submission portal.

Unfortunately, none of the above is true. Our resources are limited and oftentimes these completed projects would not even include consent forms that adequately covered copyright and sharing permissions. Therefore, early intervention in the project development stage has been extraordinarily helpful. This way we reach faculty prior to project start to answer any questions they may have about designing a project appropriate for library collaboration and can provide sample consent forms that cover a wide variety of permission and copyright options. This early intervention also allows us to plan ahead for upcoming projects and minimize the number of “surprise” digital collections that can turn up on one’s desk.

For our digital library partners outside of campus, our expectation is that collections are delivered to us either via the cloud or an external drive. However, external partnership comes with metadata training and templates as well as some expectations and dedication on behalf of the partner organization’s staff. We’ve tried this approach with our faculty in the past with mixed results. Further, oral histories often have more moving parts than a straightforward digitized manuscript collection. Therefore, we’ve started setting up structured cloud drives for use in faculty oral history collections. Our campus uses Microsoft Teams and SharePoint for shared storage. Once we’ve discussed the upcoming project with the faculty partners, we set up a Teams drive for the project which includes all of the documentation and consent forms discussed in the initial meeting. Every recording gets its own folder which should be named after the interviewee. Each interviewee folder will eventually contain the recording file, the transcript, the signed consent forms, and any other information deemed necessary. This way there is no excuse for poor file management. We also upload simple READ ME instructions into the drive so faculty partners know what to do within the drive and can stay on top of the process. This READ ME file includes links to a “submission form” that is used to capture as much data about the interview from the faculty partner as possible. Metadata collection can be challenging from our faculty partners who have no metadata experience and no inclination to learn that skill. By using a simple online form (we use Google forms) we can collect the most salient points. Then, our Digital Projects Librarian can quickly export the entries into a spreadsheet and massage the results into usable descriptive and administrative metadata. While these are very simple, common-sense techniques and strategies, we’ve found them to be most effective at quickly and efficiently aiding in the development of successful oral history projects while both managing campus expectations and being mindful of staffing restrictions.

Lessons Learned

This process has provided several learning opportunities for us that are specific to both digital asset migration and oral history management. While integrating Aviary into the traditional LCDL user experience proved straightforward from a technical standpoint, it became clear that this integration would cause a significant change to our staff’s workflows for oral histories. By continuing to add items to ResourceSpace for backup purposes alongside their presence in Aviary, we were effectively doubling our commitment to the ingestion and management of oral histories for LCDL. Though oral history collections rarely arrive in large batches, we realized that this process could become cumbersome for staff over time if we didn’t focus on developing methods to ease this new workflow. This lesson led us to the creation of the previously mentioned custom plugin in ResourceSpace that generates Aviary-compliant CSV files for batch imports. Through this process, the initial work performed in loading items to ResourceSpace can also complete a portion of the work needed to load to Aviary. It has also led us to plan for future work to leverage the ResourceSpace and Aviary APIs to automate the process of loading items more fully from one system to the other.

Additionally, the close integration of Aviary items into a unified catalog introduced another layer of technical complexity to our infrastructure. The Apache Solr index feeding our catalog’s search results now houses the combined feeds of Aviary and ResourceSpace. Further, item display pages in the catalog now use hooks in those Solr documents to correctly display Aviary’s embed functionality. While it wasn’t difficult to make these changes to our infrastructure, they introduced new challenges for LCDL staff in how to approach troubleshooting. After all, even with years of training, we all occasionally make mistakes during the metadata creation and item loading process. Furthermore, the public is often quick to find and point out errors that make it into production. The integration of Aviary into this mix means we had to train and prepare staff for what to do when errors arise, and how and where to resolve them.

In addition to the above technical workflow changes, we also learned that migration of legacy oral history transcripts can be very time consuming, especially if the format of the original transcript is dated or heavily formatted. Having a small reserve of funds set aside to pay for online transcription services is incredibly helpful in this situation. While migrating a very early oral history, we discovered that the 50+ page transcript was available only as a PDF and was formatted as a multi-column table with inaccurate time-stamping. Manually removing this formatting and correcting the transcription errors would take at least a full day of work. However, for less than what we would pay our oral historian, we were able to send these problem files out for re-transcription using an online service, and were returned transcripts that only required a brief review. This was a cost effective solution that freed up the time of our oral historian so they could continue working on other projects. Not to mention the frustration that this saved our staff.

Finally, as with any migration project, it is important to document everything. The notes that were recorded while testing out migration techniques in Aviary certainly weren’t fit to be shared broadly, but they were vital for the documentation we produced later. While determining how to both add new content as well as migrate existing content into a platform of this nature, it is not uncommon to write ourselves little “cheat sheets” or notes. Don’t throw these away! Very often these things can quickly and easily be formatted and fleshed out into a manual or migration checklist that can be passed on to others to assist in completing the project.

Conclusion

We are in the early days of our migration of legacy oral history materials to Aviary. While we have largely thought through how we want to integrate new Aviary materials into both the staff workflows and the discovery and presentation of LCDL, we still have extensive remediation of legacy materials to perform before we can bring them live on Aviary and embed them into LCDL.

However, with Aviary we now have the flexibility and potential to not only support our existing oral histories in the manner that we prefer, but also the capacity to take on new oral history projects. We’ve developed manageable workflows to support faculty driven oral history projects and now have the capability to support a dedicated oral history platform. As such, we are working on branding and launching the Lowcountry Oral History Initiative (LoHI) which is essentially a third pillar of the overall ‘Lowcountry’ project alongside the Lowcountry Digital Library and the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative. Under the banner of LoHI we hope to cultivate relationships between the Lowcountry Digital Library and various archival and community organizations to record, preserve, and make available audio and video recordings that document the memories of historically marginalized communities. Through Aviary and the Lowcountry Digital Library, we can continue to service our partners and community. We look forward to steadily adding new and varied oral history collections to Aviary while we ensure that new and legacy cultural heritage oral histories in LCDL are presented with a robust new look and feel.

About the Authors

Tyler Mobley is the Digital Services Coordinator for the College of Charleston Libraries. He serves as co-Director of the Lowcountry Digital Library and Technical Director of the South Carolina Digital Library. He holds an MLIS from the University of South Carolina. His research interests include digital asset management and preservation, digital repository systems development, library information technology management, and digital scholarship.

Heather Gilbert is the Associate Dean of Collection and Content Services for the College of Charleston Libraries. She serves as Associate Director for the Coastal Region of the South Carolina Digital Library. She holds an MFA from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and an MLIS from the University of South Carolina. Her research interests include academic content acquisition and management strategies, digital asset management and preservation, digital scholarship, metadata aggregation, and archival/cultural heritage repository management.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply