by Kara Long and Erin Yunes

Introduction

Beginning in fall 2023, librarians in the Data Services unit at Virginia Tech University Libraries introduced Obsidian as a data visualization and metadata tool for working with relational datasets. Obsidian is a lightweight, versatile note-taking and personal knowledge management (PKM) software designed for creating and managing linked text files. [1] Obsidian is free to download and use, and while it is not an open-source product, its development team has committed to the use of open formats and made the tool extensible and highly customizable through the use of open plug-ins and themes.

In this article we describe the use of Obsidian on two different research project teams with very different methods and objectives in their respective fields: the Rematriation Project, and the Dangerous Harbors project. We will reflect on successes, lessons learned, and areas for further exploration.

Data Services at Virginia Tech University Libraries

The Virginia Tech University Libraries (VTUL) serves over 38,000 students from the main campus in Blacksburg, Virginia to satellite campuses and research centers across the state, in Washington D.C., and internationally. Established in 1872 as the Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College, the university has since grown in its land-grant mission to offer nearly 280 undergraduate and graduate majors.

The Data Services unit of VTUL facilitates access, management, and analysis of data for both internal library operations as well as faculty- and student-led research teams and initiatives. Data Services’ responsibilities include library catalog data, the data repository (VTechData), and instruction in data collection, analysis, and documentation. As a team of functional specialists, Data Services supports research projects across a range of disciplines with varied research data practices and needs. We also support training and supervising students engaged in gathering, extracting, or preparing research data. The training we offer ranges from one-time workshops to ongoing partnerships with researchers, supervising students, and providing leadership in data collection and processing throughout the research lifecycle.

Kara Long, Assistant Director for Metadata Services, and Dr. Erin Yunes, CLIR Community Data Postdoctoral Fellow, began experimenting with Obsidian in Fall 2023 while working on the Rematriation Project team. The Rematriation Project is a partnership between VTUL and the Aqqaluk Trust (AT), a community organization based in Kotzebue, Alaska. In the same semester, Kara introduced Obsidian to the Dangerous Harbors project research team. Inspired by feedback from both of these teams, we sought ways to make data entry, descriptive metadata work, and linked data concepts more engaging and accessible for the undergraduate and graduate students, as well as community members, working on these projects.

Obsidian

Obsidian is a light weight, free-to-download application that runs locally and does not require a network connection. It is often referred to as a note-taking application or a tool for “personal knowledge management” (PKM). Creators, Shida Li and Erica Xu, developed and first released Obsidian in March 2020. As of the writing of this article, the latest Obsidian release is version 1.8.10, released in April 2025. The Obsidian application can run on Windows, Linux, or Mac operating systems, and mobile versions are available for iOS and Android devices. The development team hosts a Discord server and forum available to users. [2]

While it is not a metadata management system in the traditional sense, the use of Markdown syntax, bi-directional linking, graph views, tags, and YAML front matter make it a powerful tool for building and organizing a customized, structured knowledge base. Obsidian stores all files, or “notes,” in markdown on the user’s device. A key feature of Obsidian is the creation and management of these notes, which can be interconnected with links. This has been a useful teaching and demonstration tool, visually illustrating the semantic relationships and networks, connections that are not always immediately obvious in linear note-taking systems or spreadsheets.

The tools typically supported by the Data Services unit can require training and a level of technical expertise that not all participants on the research teams possessed or needed. Especially when working with community partners, not all collaborators had the time to invest in learning highly technical systems. Despite this, it was important to find ways to engage all the project stakeholders in conversations about the data we were gathering. We were willing to investigate unconventional tools to do so, as long as those tools aligned with our team’s values and community-driven goals. We wanted to balance our desire to develop our teams’ skills and understanding with our need to create rich, accurate, and reusable datasets. Using Obsidian allowed us to scaffold discussions in a way that minimized the need for prior technical knowledge, while making participation more accessible.

Case Study 1: The Rematriation Project

The Rematriation project is co-led by Dr. Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq, Assistant Professor of Professional and Technical Writing at Virginia Tech, and leadership of the Aqqaluk Trust, an Inuit-led and Inuit-serving community organization, based in Kotzebue, Alaska. [3] The Rematriation project is an Indigenous-led initiative that aims to empower communities through digital archiving to create, preserve, protect, and return access of Iñupiat cultural, scientific, and community knowledges. This project emphasises Indigenous data sovereignty (IDsov) and aims to build local capacities for archiving and digital literacy. Throughout this project, the team regularly discussed how and why to implement and practice the tenets outlined in the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. [4] These principles have deeply informed how we approached our work and have been especially informative for those team members with a background in scholarship and research. The principles alone, however, do not fully meet the needs of community members in navigating decisions around data governance and building new or reimagined relationships with researchers. Complementary frameworks and tools, based in local knowledge and experience are needed to bridge the gap between high-level guidance and the day to day work of building more equitable networks and systems for information heritage.

The Rematriation Project is structured around four central goals:

- Digitize and catalog tribal materials such as papers, photographs, recordings, and notes.

- Develop tools and curriculum to build local capacity for digital archiving, including metadata literacy and use of accessible digital platforms.

- Create and test a prototype digital archive, designed for Inuit users, that links to and helps organize existing archives.

- Establish protocols for Indigenous data and research sovereignty to ensure communities retain authority over their knowledge.

The term “rematriation”—used by Unangax̂ scholar Dr. Eve Tuck—describes Indigenous-led processes of returning and restoring cultural knowledge. [5] This framing reflects a decolonial approach to stewardship, placing Indigenous priorities, technologies, and community decision-making at the center. At the heart of the Rematriation Project is a commitment to restoring community autonomy over cultural memory and knowledge production. This project reimagines the digital archive as a living, community-owned system that supports IDsov and culturally grounded stewardship.

To achieve these goals, the archive must first be usable and accessible, especially in contexts like the Arctic, where connectivity and infrastructure can be limited. Obsidian’s lightweight design and extensive customization options made it an ideal tool for developing an engaging, flexible, and offline-accessible tool to prototype our archival work.

Equally essential to the success of this archive is its ability to support reflexive and culturally appropriate metadata practices. In early community development meetings held in October 2022, Rematriation Project community partners emphasized the need for the archive to reflect and incorporate localized terms for any materials the system may hold. This was not only a design preference but a foundational requirement: the archive must reflect local knowledge systems and naming conventions, rather than overwrite them or impose westernized standards.

Metadata as Relational Practice

Metadata creation and linked annotation play a central role in the Rematriation Project’s goal to recontextualize and recover Inuit knowledge from settler archives. Obsidian’s markdown-based structure and customizable tagging made it possible to design an archival prototype that foregrounds Indigenous terminologies and relationships. The use of Obsidian allowed us to ensure that digital materials could be linked, interpreted and retrieved in ways that are meaningful to local users.

The archival prototype we built used a sample from the research of Caleb Pungowiyi, a Siberian Yupik leader whose materials, spanning from the 1980s to early 2000s, include photos, notes, policy documents, and scientific observations. His work on Arctic ecology and climate change brought Indigenous perspectives to national and international policy decision-making. [6] We digitized and described over 6,500 files with the support of the VTUL Digital Imaging Lab. The Pungowiyi family loaned the materials to the Rematriation Project and, following a post-custodial, community-first model of archiving, were returned to the family after the digitization process.

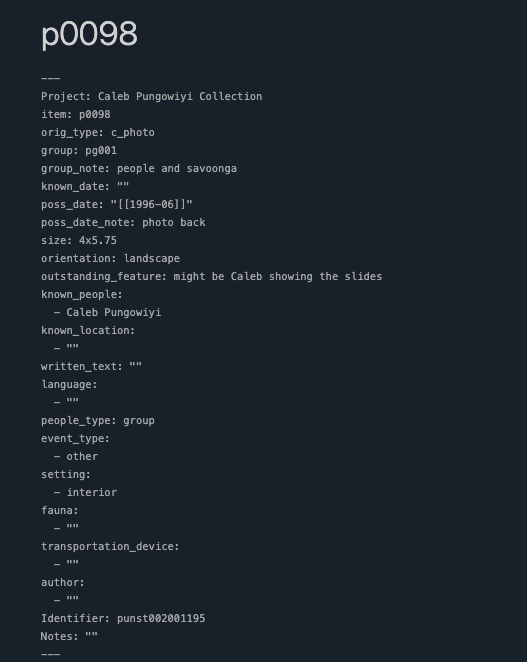

Focusing exclusively on a portion of the Pungowiyi’s photographs, we built the first version of the Obsidian prototype vault, where each photo became an individual markdown file or note. We used OpenRefine [7] to clean and format metadata generated by the digitization lab and the Obsidian plugin JSON/CSV Importer, [8] to batch create notes for 820 image files. This first vault incorporated YAML front matter to ensure consistent metadata inputs with tags and backlinks to reflect relationships and recurring themes. Using the Map View [9] plugin, we used geolocation metadata to generate an interactive map, which gave us a visual representation of the places documented in Pungowiyi’s research.

Figure 1. A screenshot of the YAML frontmatter at the head of a note describing photograph “p0098” of the Caleb Pungowiyi Papers

In the second phase of the prototype, Aqqaluk Trust staff member Dylan Paisaq Itchuaqiyaq joined in the development process, testing the system and contributing localized metadata, strengthening the archive’s community relevance. After an initial round of metadata enhancement, Paisaq identified several “quality of life” improvements—practical features that would make working in Obsidian more efficient and user-friendly. These included the need for synonym matching to connect different terms, streamlined bulk tagging, and image gallery metadata creation options. This phase was an important step to ensure that the archive could support consistency and flexibility as it scales for broader community use.

Bridging Technical and Cultural Needs

Obsidian was particularly effective in bridging technical and community needs. It supported ethical documentation of metadata terms chosen by Iñupiat collaborators and enabled non-technical contributors to work directly in a legible, non-proprietary format. Above all, it was essential to create a space for community members to define metadata categories and control the language they chose to use to describe the archival materials in the prototype vault. Because selected materials may be designated by community members as containing Traditional Knowledges (TK) or sensitive family stories, the knowledge that each vault was available only on a user’s machine (and not in a shared spreadsheet or drive), allowed users to capture their thoughts freely.

Case Study 2: Dangerous Harbors

The Dangerous Harbors Project aims to aggregate and make accessible narratives of escape from servitude and enslavement in Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina during the seventeenth century. Dr. Jessica Taylor, Associate Professor of Oral and Public History at Virginia Tech, leads the research team in this on-going project. With the support of an NEH planning grant for the 2023-2024 academic year, Dr. Taylor and a team of faculty, students, and librarians digitized, transcribed, and generated a dataset from court records collected from three Virginia counties related to escape attempts of enslaved and indentured persons.

While these are public records, seventeenth-century handwriting and rhetoric are challenging to read and comprehend. Additionally, these records are often stored at the county- or colony-level and siloed from records in neighboring jurisdictions documenting similar or related proceedings. Creating a dataset that crosses county-lines allows us to expand our understanding of unfree persons and the social and legal networks of the period. The team seeks to build on the work of projects such as Enslaved.org and Freedom on the Move, and we have aligned our data model with the Enslaved.org Ontology [10] to increase interoperability and reuse with similarly-aligned data gathering projects.

The Dangerous Harbors dataset consists of three record types: persons, events, and sources. Each person-record represents one individual, uniquely identified in the primary source documents. Each event-record represents a single event (such as a legal proceeding or hearing), described in the primary source documents. The primary sources are represented by source-records and citations. As a collection of court orders, the documents are already itemized by event: each entry in the order books describes one proceeding. The persons involved, however, may be recorded several times across multiple events; and, multiple individuals are typically recorded in association with each event. The roles of individuals vary across events. For example, an individual acting as a jury member in one proceeding may be providing legal counsel in another. As sources were transcribed, the team populated a shared spreadsheet to record persons and events. Each person and event were assigned a unique identifier, allowing us to associate individuals, events, and the documentary sources with each other.

Metadata Preparation

Despite using a flat spreadsheet to gather the data from the source material, our conceptual model was based on linked data principles, which we were able to demonstrate and share with students using Obsidian.

In the court records, people with the same or similar names were often recorded with very little to differentiate them. Names were also often recorded with variant spellings or as partial versions. We used contextual evidence from the sources to make these determinations, such as the point in time when the proceeding occurred, the locations mentioned, and the presence or absence of other persons previously associated with the person in question. We recorded notes about near-matches, confidence level, and any relevant evidence for ambiguous cases.

We used the Obsidian plug-in, JSON/CSV Importer to create a note for each person-record and each event-record from our shared spreadsheet into a new Obsidian vault. The JSON/CSV Importer plug-in uses a Handlebars template file, stored in the Obsidian vault, to configure imported data, including creating properties in the YAML frontmatter, and adding suffixes to create unique note filenames. [11] In Obsidian, all notes within the same folder must have a unique filename, so each note has a unique file path. Having assigned a unique identifier to each person-record and each event-record, we used these identifiers as the note filenames. We imported the person-records and event-records to Obsidian folders labeled “Persons” and “Events,” respectively. We used the aliases property to record each person’s name, when known. This allowed us to reference and retrieve notes for each person either by their name or by their unique identifier.

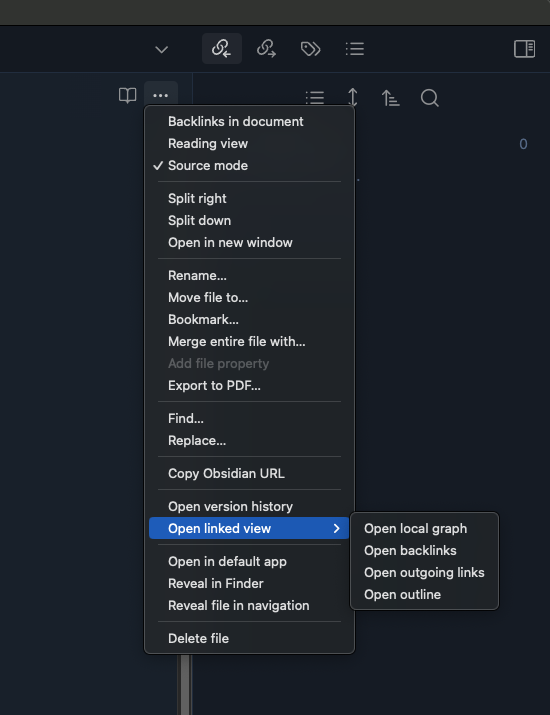

Using the double bracket syntax (see later), we linked persons, events, and sources. Obsidian can display these links through different view options. From an open note, a user can select “Open linked view” from the “More options” menu. From this menu, users can dynamically create the following displays: a local knowledge graph, showing the open note and all linked notes; a list of notes that link back to the open note (called backlinks); a list of all outgoing links; and an outline view, showing a more hierarchical arrangement of headings and links. In addition to these views, users can also access a knowledge graph of the entire vault from the main navigation menu, called “Open graph view.”

Figure 2. This screenshot shows the More Options menu, and the different views available to show how notes are linked together in Obsidian

Staging for Data Publication

Over the course of the project, we imported approximately one hundred notes describing persons and seventy notes describing events. We chose this subset of the data because it had been gathered early on in the life of the project, and team members were familiar with the idiosyncrasies of the records used to derive the data—which provided another opportunity to educate students and new team members about what they might encounter in working with seventeenth-century records. This is a small representation of the complete dataset, which now includes over 340 events and roughly 850 persons. The dataset will grow as work on the project continues. Using a subset of the data was suitable for demonstrating the utility of assigning unique identifiers to each event, person, and source, and defining the relationships between them. This proof-of-concept also prepared the team for conversations about modeling the Dangerous Harbors dataset for a linked open data (LOD) environment. While Wikidata and Wikibase are more user-friendly than creating and publishing RDF or serialized XML as linked data, there is still a significant learning curve for many researchers and students who are unfamiliar with linked data concepts in general. Obsidian was a vital visual aid and easy-to-use tool that could demonstrate in real time the advantages to modeling data this way.

The Dangerous Harbors project has several aims, including the development of lesson plans and educational resources for teachers and community groups, and the publication of the dataset and corresponding records in formats that are accessible and reusable. Working with Obsidian has provided a more inclusive environment to discuss linked data with stakeholders and team members who may be new to these methods of knowledge organization. And, it allowed us to explore different ways of representing the relationships in the data before transferring the data to a Wikibase.cloud instance. [12] The Wikibase software offers more in terms of data publication, querying, and integrating data from external sources; however, we plan to continue to use Obsidian as a staging area and jumping-off point to engage new and returning team members in data modeling discussions. At this stage, the team continues to use a shared spreadsheet to export data to Obsidian and Wikibase; however, viewing the data in Obsidian has revealed errors and inconsistencies that were difficult to detect when working in a spreadsheet alone.

Technical Infrastructure and Plugins

An Obsidian “vault” is the top-level folder containing all of the sub-folders and files (or notes), attachments, and configuration files that the user is able to access, edit, and link while using Obsidian. A user can create several vaults or switch between vaults, but links can only be created within a single vault. For both the Rematriation Project and Dangerous Harbors projects, research teams worked with a discrete dataset, which we worked with in separate vaults.

The double bracket syntax ([text]) in Obsidian, creates a link between one note and another. Inserting the hash character (#tag) before any text creates a tag. Tags allow users to sort notes into user-defined categories. From the navigation pane, a user can view all the tags they have created in Obsidian and navigate amongst notes containing only those tags. Tags can appear in the body of a note or in the front matter as a property of that note. Obsidian note properties are configured and stored as YAML frontmatter. [13] Properties in Obsidian can be added to templates that can then be used to create new notes. For example, if a user creates a new note about an entity in a dataset, they can generate that note from a template with the appropriate properties describing that entity ready for entry. From a template, a property can also be “pre-filled” with values (such as the dates or tags) appropriate for that particular note.

Users can create properties to use across all notes within a vault. When creating a new property, a user provides a unique name for that property and selects a data type. Obsidian supports the following property data types: text, list, number, checkbox, date, and date and time. Properties can only be populated with values of the selected data type. There are three default properties that have fixed data types in Obsidian: cssclasses, tags, and aliases. The cssclass property uses a list data type and allows you to apply css styling to a note or group of notes. The tags property data type is similar to list, but can only be populated with existing tags or newly created tags. The aliases property is also similar to the list data type but stores variations on the name of the note that allows the user to retrieve or reference that note by either its name or any of its aliases. Use of these properties is not required in any given note or project, but could be useful for filtering or searching for notes by tags and alternative text, or applying specific styling. We did not take advantage of these specific properties in our projects.

Users can extend the features and functionality of Obsidian with plugins. A library of core plugins and community-contributed plugins is accessible from the Obsidian options menu. It is necessary to have an active network connection to access an up-to-date list of all of the options available and download them. Throughout our experimentation with Obsidian, we found several community plug-ins that were essential to using the application for exploring research data, including: Dataview, JSON/CSV Importer, Image Gallery [14], and Mapview.

Through the use of templates, folder structures, plug-ins, and properties we created Obsidian vaults that, themselves, acted as templates and instruction manuals for data collection and sharing. [15] For both research teams, we used data initially gathered in spreadsheets to populate an Obsidian vault with notes, which were shared with project team members. Using copies of a shared vault, team members were able to experiment, enhance, and explore the dataset in their own Obsidian instance and provide feedback on the data that had already been gathered, make changes, and share those changes back with the team. Of course, there is a risk of conflicting data when multiple team members work on their own copies of the dataset, and in practice, the data may not always align perfectly. Obsidian allows team members to document their observations or proposed changes directly in the body of a note for later discussion. When conflicts or ambiguities arise, they are resolved collaboratively: for the Dangerous Harbors Project, decisions are made by the project leaders in consultation with subject specialists; for Rematriation Project, the community partners would determine the appropriate resolution.

Obsidian also supports a number of export options and community plug-ins that facilitate export in a variety of file formats, such as PDF. The Dataview [16] plugin and the Table to CSV Exporter [17] plugin supports the export of notes out of Obsidian as CSV. Extracting data and importing it to another system does require some knowledge and comfort with data transformation.

Reflections and Recommendations

Obsidian allows users to create and experiment with different and various arrangements of their own research data and observations, thus making visible the impacts of the different choices that confront anyone gathering and generating data. Without an understanding of how an information system will act on the given information (in this case, descriptive metadata), the system becomes, “capricious, untrustworthy, and unpredictable”. [18] For example, it makes visible the choice to model the data based on an event or a person, or when to create a new “note” (i.e. entity), or when to allow that entity to simply be represented by a string—and what affordances that does or does not allow within the data set. These are concepts that can be difficult to explain and difficult to grasp quickly for users or operators of a system but can become more meaningful to a participant and co-creator of that system.

In comparison to asking participants (either community partners or students and faculty) to “fill in” a spreadsheet with values that will later be passed on to a library specialist in data visualization or digital platform management—using Obsidian allows the participants to both plan an action (i.e. create a relationship or link between a person and a place) and execute that action. Even as an exercise, this can help build trust within research project teams, so the library and the way library systems operationalize data seem less like a “black box.” It also contributes to team members’ information literacy, setting a common environment to engage non-library specialists in discussions about how and when to use controlled vocabularies, when to form links between concepts, and how those relationships should be defined.

Decisions made by the research team and modeled in Obsidian can be translated into library systems, if appropriate for the project. We tested using a Python script [19] to generate a CSV file of all of the note filenames, properties, and text bodies in our Obsidian vaults as a way to “extract” the data added by team members. Because Obsidian vaults are essentially folders containing structured text files, the Python script relies on the consistent use of properties and tags to extract the file names and return the content of those files as structured data. We could then use the CSV export as part of an ETL pipeline to generate records in a digital collections platform or create entities in open knowledge bases, such as Wikidata or Wikibase.

Conclusion

Obsidian can be an effective bridge between narrative and structured data, between scholarly and community perspectives, and between material archives and digital tools. Obsidian proved to be a valuable tool for research teams seeking a way to create structured but flexible metadata, easy onboarding for contributors, transparent file storage in open formats, and ways to integrate narrative with metadata capture. As a prototyping tool, Obsidian allowed project team members with varying levels of proficiency with traditional data tools to experiment with high-level knowledge organization concepts.

There are many options and resources available for learning more about Obsidian. Obsidian users and developers offer lots of good ideas on the official message board. The community plugins pages that are created and maintained by users offer a wide range of documentation and examples. Obsidian users are also easy to find on Reddit, YouTube, and other parts of the internet. There is no one, canonical source of information or inspiration for using Obsidian – unlike an enterprise system or more scholarly-focused tool. [20] It is a constantly evolving landscape, which can be both exciting and challenging equally. We are looking forward to seeing how these tools continue to change and how and if PKM tools become more widely adopted in academic projects.

References

Bade, David. 2012. IT That Obscure Object of Desire: on French Anthropology, Museum Visitors, Airplane Cockpits, RDA, and the Next Generation Catalog. Cataloging and Classification Quarterly 50:316-334. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2012.657606

Carroll, S. R., Garba, I., Figueroa-Rodríguez, O. L., Holbrook, J., Lovett, R., Materechera, S., Parsons, M., Raseroka, K., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., Rowe, R., Sara, R., Walker, J. D., Anderson, J., & Hudson, M. 2020. The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Data Science Journal, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2020-043

Enslaved.org. Enslaved.org Ontology [Internet]. [cited May 21, 2025]. Available from: https://enslaved.org/ontology

Tuck, Eve. 2011. Rematriating Curriculum Studies. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy 8(1): 34–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15505170.2011.572521

Notes

[2] Join the Community [Internet]. [updated 2025]. Obsidian; [cited May 21, 2025]. Available from: https://obsidian.md/community

[3] The Rematriation Project [Internet]. [updated April 2025]. Blacksburg (VA): Virginia Tech University Libraries and the Aqqaluk Trust; cited [May 18, 2025]. Available from: https://rematriate.net

[4] Carroll, et al., “The Care Principles for Indigenous Data Governance,” 43.

[5] Tuck, “Rematriating Curriculum Studies,” 37.

[6] https://www.calebscholars.org/about-caleb/

[8] The JSON/CSV Importer plug-in was created by Obsidian user furling42 and is available on the Obsidian Community Plug-Ins page or on Github: https://github.com/farling42/obsidian-import-json

[9] The Map View plugin was created by Obsidian user esm and is available on the Obsidian Community Plug-Ins page or on Github: https://github.com/esm7/obsidian-map-view

[10] Enslaved.org Ontology: https://docs.enslaved.org/ontology/

[11] Handlebars templating language: https://handlebarsjs.com/guide/

[12] Wikibase.cloud instance: https://dangerousharbors.wikibase.cloud/wiki/Main_Page

[13] Properties [Internet]. [updated August 21, 2020]. Obsidian Help; [cited May 21, 2025]. Available from: https://help.obsidian.md/properties

[14] Image Gallery was created by Obsidian user, Luca Orio. It is available on the Obsidian Community Plug-Ins page or on Github: https://github.com/lucaorio/obsidian-image-gallery

[15] A copy of our Obsidian vault is available on the project team’s Github: https://github.com/rematriation/Obsidian-Vault-documentation. The media files and the majority of the item-level metadata have been redacted. The available vault does contain some build notes, properties, templates, and plug-ins used by the Rematriation project team.

[16] The Dataview plug-in was created by Obsidian user, Michael Brenan. It is available on the Obsidian Community Plug-ins page or on Github: https://github.com/blacksmithgu/obsidian-dataview. Dataview allows users to use query language for sorting, filtering, and extracting data from their notes using a JavaScript API.

[17] Table to CSV Exporter was created by Obsidian user Stefan Wolfrum. It is available on the Obsidian Community Plug-ins page or on Github: https://github.com/metawops/obsidian-table-to-csv-export

[18] Bade, “IT That Obscures,” 320.

[19] The authors welcome requests to share the Python script. Please get in touch over email.

[20] Obsidian user Nicole Van der Hoeven’s tutorials on YouTube and on her Obsidian site have been especially helpful in learning how to use the application and in showing use cases for different plugins. You can find her work here: https://notes.nicolevanderhoeven.com/Fork+My+Brain

About the authors

Kara Long is the Assistant Director for Metadata Services at the University Libraries at Virginia Tech. She provides metadata consultations, training, and development for library users and researchers. She brings a background in cataloging and digital collections to her work. Her current research is focused on collaborative, community-based approaches to knowledge preservation and information heritage.

Dr. Erin Yunes is a Professor and Departmental Coordinator in the School of Art at the American College of the Mediterranean (ACM-IAU) in France. A former CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow in Community Data, she specializes in data management, digital cultural heritage, and equitable information practices. Her research focuses on community-led strategies for strengthening access to digital cultural resources.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply