by Ethan Gruber, Chris Fitzpatrick, Bill Parod, and Scott Prater

I. Introduction

Libraries have become repositories for increasingly complex sets of information. Several decades ago, libraries typically only managed printed materials: books, periodicals, maps, etc. A single cataloging record described each object, and this record rarely had to change since later editions of the work were assigned new records. Today, libraries manage traditional materials in addition to vast sets of digital resources: databases, Geographical Information System datasets, images, audiovisual materials, and many others. Each intellectual object requires metadata for searchability, and the better the quality of this metadata is, the more likely library patrons will be able to access objects through public interfaces.[1] XML has become the standard for metadata encapsulation, lending itself easily to internet transmission and machine processing. Libraries throughout North America and Europe commonly use Dublin Core, MODS, TEI, EAD, and VRA Core[2] to describe various types of bibliographic, archival, or visual resources collections. These metadata records are often not static, but rather need to be modified over time, and therefore institutions have devoted resources to developing applications and workflows for editing them.

Structurally complicated XML (which describes all those listed above with the exception of Dublin Core) is difficult to author or edit in traditional HTML forms, which also have limited validation capabilities. A working group was formed to devise a new standard, XForms, to address the inadequacies of earlier form types. XForms 1.1 is a World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) XML specification, published October 2009[3], that defines the operation of a form with the model-view-controller (MVC) relationship. XML structure is encapsulated in the model while controllers manage interaction with web services, action handlers, background processing, and other features to present a form to the end user. The view enables repeatable elements and real-time validation. Essentially an XForms application can be used to create XML metadata to the fullest extent the schema allows and then saved to (or loaded from) a datastore that communicates via REST or SOAP.[4] The XForms submission enables your XForms model, e. g., a MODS record, to be processed against an XML Pipelining Language (XPL) call to transform that instance into a Solr document and post it to an index. XForms applications provide a powerful set of tools for data creation and manipulation, as demonstrated by some projects related to library workflows that are described in this paper.

II. Support

A. Required expertise

XForms is a complex standard that was designed to be powerful and flexible enough to fill the needs for complex, dynamically-created and modifiable forms. Like its close cousin, XSLT, it inhabits the grey zone between being a programmable toolkit and a data serialization standard. Simple forms can be created fairly rapidly, though they will be more verbose than their HTML counterparts. However, the benefits of XForms do not really begin to manifest themselves until you begin to design forms with complex structures, dependencies, and runtime behaviors. If all you want to do is create a simple, static address form, you would be better off sticking with HTML. However, if you want to create a metadata editor that fully encapsulates and enforces the constraints of a mature and rich standard, such as MODS or EAD, the time spent mastering XForms will pay off in the long run.

So what are the skills an XForms designer should have? First and foremost, they should be familiar with XML, and comfortable navigating complicated XML documents. XForms uses XPath syntax and functions to express relationships and behaviors, so the designer should have a good working knowledge of XPath. The designer should also understand the XML Schema standard, as it is used to express constraints and define validation rules.

The designer should also be familiar with the metadata standard(s) that the form will generate. In the context of libraries, this means a good working knowledge of Dublin Core, MODS, EAD, TEI, VRA core, and other more specialized XML metadata standards used in the library field. These standards will be used to create the model (explained below); data entered in the form will be serialized into the XML standard defined in the model.

Finally, but perhaps most importantly, the XForms designer should be a skillful, sensitive user interface designer. No matter how large or complex the form, or how rich the metadata that is generated from it, the form will be of no use whatsoever if the end users find it clunky, non-intuitive or difficult to use. In this regard, the power and flexibility of XForms can be seductive, especially to the technically proficient XML wrangler. The designer cannot lose sight of the fact the form will be used by people who are more interested in entering data quickly and accurately than they are in fancy interface tricks and ornate data structures.

If you’re fortunate to have on staff a developer with all these qualities embodied in one person, then you’re in a very enviable position. If the expertise in your library is more diffusely distributed, as is the case in most places, then the work of designing an XForms-based interface may fall to three people: a primary developer, who will create the XForms document, a metadata librarian, who will communicate the functional requirements of the form, and help guide validation rules and local encoding practices, and an interface designer, who will work with the XForms developer to map the metadata model onto the controls to produce a user-friendly form. Depending on the degree of overlapping expertise, the core job of developing the form may be shared to a lesser or greater extent; but no matter who does the work, about 35% of the time spent creating the first complex XForms interface will be consumed with defining the metadata model at one end (the output), and the user interface design at the other end (the input screen). The remaining 65% of the time will be used to actually create the XForms to bind the two together. As time goes by, the roles of the metadata librarian and interface designer will diminish, as a body of decisions and practices, embodied in a library of XForms snippets, takes shape.

B. Software

So you have the expertise in-house, ready to create an XForms-based metadata entry web application. Now what? Can you just write an XForms document, put it on your webserver, and see the form magically appear in your browser?

Unfortunately, that is not the case today. XForms was going to be the new standard for web forms back in the XHTML days, but as of 2009, XHTML (both version one and two) has been deprecated by the W3C in favor of the next-generation HTML standard, HTML 5. When the W3C dropped XHTML, it also abandoned plans to incorporate XForms into the next-generation HTML standard (opting instead to expand the current HTML forms tagset for HTML 5).[5] In real world terms, this means that browsers are unlikely to offer native XForms processing any time in the future.

But XForms itself is alive and well, it continues to be developed by the W3C XForms working group and there are a number of products available that implement the most recent XForms 1.1 standard. As XForms is its own XML specification with its own namespace, independent of any other markup standard, it can be encapsulated in an XML document of any type, not just XHTML. For example, OpenOffice 3.x+ implements the XForms 1.0 standard to create form documents. However, for the purposes of web development it makes the most sense to embed XForms markup in XHTML documents, and that’s where you’ll see 99% of the XForms out in the wild. There are a number of third-party browser plugins available, as well as server-side applications that can process an XForms document, translate it into AJAX controls with additional CSS and javascript, and send it to a browser for display without the need for any client-side software.[6]

III. Metadata Editors

All of the applications and examples discussed below were implemented using the Orbeon Forms application, a server-side web application that transforms XHTML+XForms documents into HTML documents with AJAX controls for display in the browser. Orbeon Forms is an open source product; the company offers a GNU Lesser General Public Licensed (LGPL) community edition for free download and a professional edition for purchase.[7] The authors have opted to use Orbeon due to its active and growing user community, the responsiveness of the software developers to questions, the rich set of examples and documentation created for the product and for XForms development in general, and the stability and maturity of the software itself. Moreover, Orbeon is a Java-based application that runs in Apache Tomcat, like numerous other applications that libraries use (Solr, Fedora, Cocoon, etc.).

While the Orbeon Forms source code is publicly available on GitHub, the core of the Orbeon Forms application is maintained by a small group of committers. This makes the core Java libraries of the application very stable. Application upgrades in most circumstances only require moving the XForms templates to the new application. The Orbeon developers have also included over 400 unit tests, which are automatically run by Orbeon at build time but can also be run by individual users on their own systems.

However, as with all software, there are some maintenance issues of which developers need to be aware. Initially at Stanford, some of the most time consuming issues were not related to maintaining the code, but rather to supporting all the various forms that had been released. This was the result of a deployment decision to not attempt to create a single MODS form for all users, but rather deploy multiple slightly modified MODS forms in order to address a collection’s particular needs. While this is very easy to do in the Orbeon application, it does create some support issues. Since each form is essentially a markup document that configures the MVC that is interpreted by the application, the vast majority of any desired behavioral changes must be done by editing these configuration settings, not by recoding the application. Since this can require changes to multiple configurations, this can make pushing requested global changes, such as structural changes to the metadata output, modifications to a third-party API, or a new feature desired for all collections, somewhat time consuming.

In attempting to address this issue, in August 2009 Stanford migrated to the Form Runner environment, which is a part of the Orbeon Forms CE core distribution. As stated on the Orbeon website, “Form Runner manages form types and form data, handles search, validation, and takes care of the plumbing necessary to capture, save, import and export form data.”[8] Primarily, the Form Runner code accomplishes this by making more of the MVC dynamically built, as well as adding a commonly used persistence layer for all forms running in the environment. Forms running under the Form Runner environment are rendered at runtime by common XSLT stylesheets that can dictate much of the structure of the form. Many desired global changes can therefore be made at the Form Runner level, rather than in the individual form. In addition, interactions between the forms and their datastore’s APIs can be configured in the Form Runner’s persistence layer settings. Therefore, a change to an API can be applied across the entire application rather than having to edit the REST calls defined in each of the form’s markup.

However, committing to the Form Runner environment also has its trade-offs. Most notably, the Orbeon Form Runner is currently in a beta release, meaning much of the code that drives the templating is still undergoing semi-frequent changes. While unit testing does greatly help limit unforeseen errors, there are cases where a change to a feature can unknowingly and detrimentally impact the application.

Developers investigating Orbeon are encouraged to take into consideration these maintenance factors in formulating an approach. Currently, using “traditional” XForms in Orbeon provides a very high level of application stability, but can increase the time required for administration if the number of actively deployed forms proliferate. Form Runner, while still an emerging technology with some of the pitfalls of beta software, has the upside of offloading much of the maintenance to common templates files.

A. Simple XForms document

Let’s start with a simple XForms document that outputs a snippet of MODS metadata.

<xforms:model id="hello_world">

<xforms:instance id="mods">

<mods:mods xmlns:mods="http://www.loc.gov/mods/v3">

<mods:title/>

</mods:mods>

</xforms:instance>

<xforms:bind id="my_title" ref="instance('mods')/mods:title" required="true" type="xs:string" />

<xforms:submission action="http://my.web.service/eat/mydata" method="put" id="send_it_off" />

</xforms:model>

<xforms:input bind="my_title" />

<xforms:submit submission="send_it_off">

<xforms:label>Send it off</xforms:label>

</xforms:submit>

At its most basic, an XForms application does nothing more than take the data input via controls, validate it, put it into the model, and send it off as a stream of XML.

Lines 1 – 8: The model defines the serialization of the data, its bindings and constraints, and what happens to it when it is ready to be sent off. What you put in the model is what will be sent to a web service somewhere when the user clicks “Submit”. The serialization format itself is set in the elements. Each includes a snippet of XML in the metadata format you want to output; in this case, we’ll output a MODS document. In more complex documents, you may have many models, and dozens of instances in each model. Not all models and instances need be part of the output, and you have complete control over which models and instances are used to build the final serialization.

The optional element on line 7 ties the model to a control, and defines certain constraints on this bit of the model. In this case, we declare that the /mods/title element in the model is required, and that it must be a valid string, as defined by the XML Schema standard.

The <xforms:submission> element on line 8 determines where the data will be sent once a submit event occurs. A model may have more than one submit event. XForms gives you a great deal of flexibility in chaining submissions together, sending different pieces of a model to different services simultaneously, or only submitting data upon the fulfillment of certain conditions (including, but not limited to, successfully completing and receiving a response from earlier submissions).

Lines 9-12: This is the “view/controller” part of the XForms, where the model gets embodied in traditional interface form controls. Every control in an XForm is bound to some instance in a model. The input to the control becomes the value of the bound element of the model. In line 9, the element displays a text input field on the web page. The data that was typed into the text input field becomes the value of the /mods/title element. The “bind” attribute refers to an element with the corresponding id in the model. The element, in turn, refers to an element in an instance in the model, as expressed using XPath.

Lines 10 -12 display a submit button on the web page, with the label “Send it off”. The “submission” attribute ties the button to the submit action with the id “send_it_off” in the model.

This XForms is a bare bones document. To be properly displayed in a browser, it should be combined with XHTML. Here’s the above form rendered in a HTML page:

<html

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml"

xmlns:xforms="http://www.w3.org/2002/xforms"

xmlns:xs="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns:mods="http://www.loc.gov/mods/v3">

<head>

<title>MODS Metadata Editor</title>

<xforms:model id="hello_world">

<xforms:instance id="mods">

<mods:mods xmlns:mods="http://www.loc.gov/mods/v3">

<mods:title/>

</mods:mods>

</xforms:instance>

<xforms:bind id="my_title"

ref="instance('mods')/mods:title" required="true"

type="xs:string" />

<xforms:submission action="http://my.web.service/eat/mydata"

method="put" id="send_it_off" />

</xforms:model>

</head>

<body>

<xforms:input bind="my_title" />

<br/>

<xforms:submit submission="send_it_off">

<xforms:label>Send it off</xforms:label>

</xforms:submit>

</body>

</html>

If you were to type “Codex Seriphinianus” in the input field, then click “Send it off”, your web service would receive the string “Codex Seriphinianus” in the body of a PUT request.

B. Use Case Examples

The following use cases from the University of Virginia, Northwestern, and Stanford demonstrate the kinds of problems encountered when creating metadata editors, and how XForms were used to address those problems. Some common themes emerge: mastering XForms is a continual process, and as expertise develops, forms can be more modular, with reusable form elements; that using XML to process XML is preferable to creating models of the data outside the data; and that the real power and flexibility of XForms manifests itself when it comes time to express arbitrarily complex, hierarchical and recursive relationships in a form.

Encoded Archival Description (EAD)

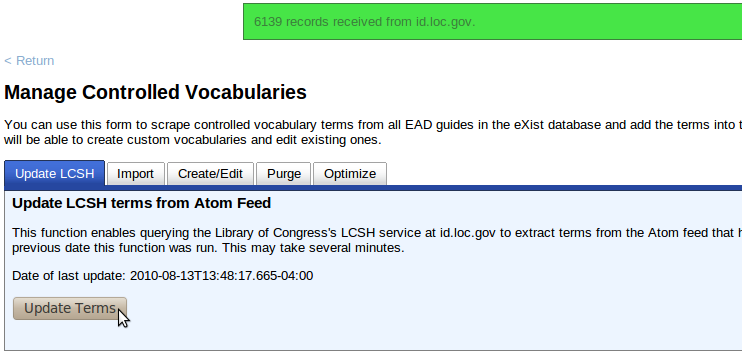

One of the major obstacles to streamlining electronic finding aid production in archives has been the technical barrier of subject specialists learning EAD XML in order to create valid documents that make use of elements in a semantically appropriate way. While as-you-type-validation in oXygen has improved quality control, many institutions are using text editors or Microsoft Word to author electronic finding aids. An XForms application that enables archivists to create complex, hierarchical finding aids without needing actual knowledge of the XML schema would be of great use to the community. The EADitor project was established nearly a year ago to tackle this challenge and has progressed significantly since its inception.[9] Much of the EAD 2002 schema is represented in the web form, but mixed content (a mix of plain text and stylistic elements, much like HTML or TEI paragraphs) is not yet supported. The application enables uploading EAD 2002-compliant guides from the “wild,” i.e., human-generated files. These EAD files cannot easily be imported into database-driven systems such as Archon or Archivists’ Toolkit since the source document is broken down into 20 or more tables, heightening the potential for data loss. EADitor includes as part of its suite of XForms applications a form for customizing the default EAD templates so that archivists can define their own data model for the core of the finding aid or subcomponents of the collection. For example, a repository may require a <unitdate> and access rights information for each item. The archivist can build this into the model so that individual elements do not have to be inserted for each new finding aid. Additionally, items can be “published” to a Solr index, which the public interface for searching, browsing, and displaying finding aids relies upon. In this sense, there is not just one web form for creating and editing EAD, but rather numerous XForms applications that the user encounters, depending on the task at hand. Some of these are as simple as a pop-up window that asks the user to choose to add or remove a Solr document or delete the XML file from the datastore. One of the most important features of EADitor is a controlled vocabulary management system.

In one of the first informal demonstrations of EADitor, it was pointed out that there should be strong authority control in several sections of the document. Subjects, along with personal, geographic, corporate, and family names should be restrained by localized University of Virginia or Virtual Library of Virginia consortium controlled vocabulary. Authorized Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) terms were also requested. TermsComponent in Solr 1.4 was used in conjunction with Orbeon’s Form Runner autocomplete widget to deliver this functionality. As a user enters text into an input bound to the widget, the value of the input is passed to a submission that queries Solr to return terms that begin with the letters that the user has typed. The Solr response is placed into an instance which populates a dynamic set of items that is suggested to the user. The controlled vocabulary manager of EADitor enables one to scrape all of the access terms from EAD files within the datastore (eXist, in this case) and post them en masse to Solr. New terms can be created and posted to Solr in addition to deleting terms. The Library of Congress provides an Atom feed for updates to the LCSH dataset, which is processed by an XSLT stylesheet called within the vocabulary manager to add or update to the Solr index all the terms that were modified after the previous time the process was executed. Although elements in EADitor do not query the service maintained by the Library of Congress directly, they do query a service running on local hardware that can always be kept up to date with id.loc.gov. Additionally, localized and LCSH terms can be suggested in parallel since they are contained in the same Solr index.

Figure X: LCSH linked data processing in EADitor

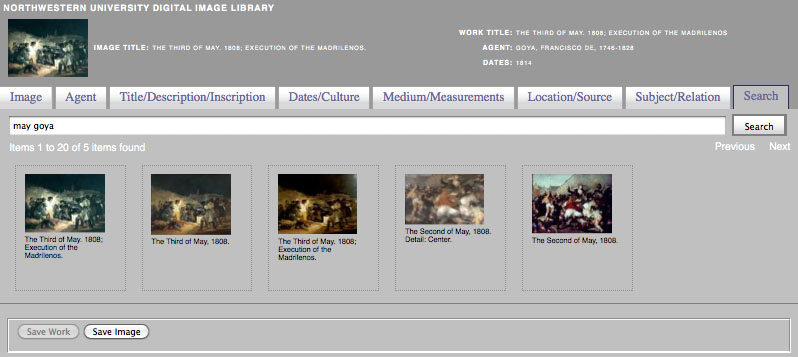

VRA Core

Northwestern University Library (NUL) is in the process of converting its Art History image collection from MARC maintained in its ILS (Integrated Library System) to VRA Core in Fedora/Solr. Moving away from the ILS leaves a functional gap in the availability of a suitable cataloging tool. The choice of VRA Core as the archival format has focused editor requirements on its descriptive model and prevalent cataloging practice in visual resource collections. This case study describes the motivations to adopt XForms and the use of XForms to create an editor for VRA Core.

Reusable Interface Widgets

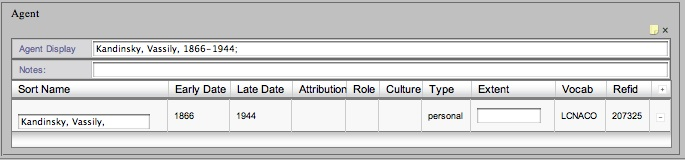

VRA Core organizes its larger descriptive model into sets, such as TitleSet, AgentSet, DescriptionSet. Each set contains repeatable groups of descriptive fields, an optional note field, and a free-form ‘display’ field that is used to combine the set’s description for public display purposes. While each set has different fields in its repeatable groups, the consistent overall structure of VRA sets means that a reasonably abstracted and repeatable ‘set widget’ can be used to support the entire schema. For example, here is the AgentSet in such a widget:

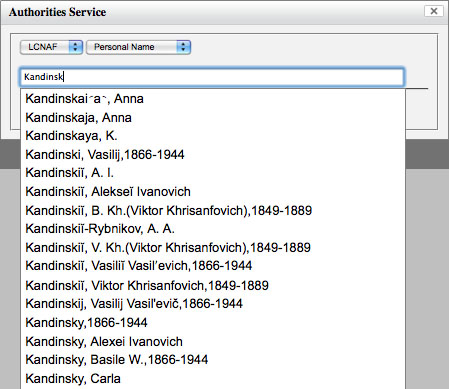

Controlled Vocabularies

Many fields in an item’s description are under authority control. At Northwestern, authorities management is done in the ILS (Ex Libris’ Voyager). To provide authorities access to this XForms editor and other collection management systems, authorities services are exposed through a locally developed web service. Since multiple authorities are available for name/term selection, a dialog panel allows the user to select authorized names and terms. The dialog includes drop-down lists to select the source authority (Library of Congress or Getty) and the type of authority record. Once the authority is selected, an autocomplete mechanism similar to the one in the EADeditor application iinteracts with the the authorities services. For example:

Custom XBL Components

Since controlled vocabularies are used for so many fields, there’s a strong incentive to make the authority files dialog easy to invoke throughout the editor. This can be accomplished by first encapsulating the dialog, its fields, authorities service interactions, and selection mechanisms in a distinct XForms component. There then needs to be a way to associate the encapsulated dialog with controlled fields, then invoke it. Orbeon supports the W3C XML Binding Language (XBL) for binding an XForms MVC component (the authorities dialog in this case) with a custom namespaced element. By using XBL to create a custom XML element for field input which invokes the dialog widget when entered, that element can easily be used for any field that should be under authority control. The interface, local data, and behavior is encapsulated, then made available in an editor form by using a simple custom XML element. Here is an example structure to declare a custom XBL widget and bind it to a custom XML element.

The authorities dialog is defined in a custom component XBL file that provides its models and views between <xbl:template/>:

<xbl:xbl xmlns:xbl="http://www.w3.org/ns/xbl" xmlns:nulAuthLkup="our_custom_namespace_uri"> <xbl:binding id="nulAuthLkup-authorities-lookup" element="nulAuthLkup|authorities-lookup"> <xbl:template> Dialog's view and model elements in here </xbl:template> </xbl:binding> </xbl:xbl>

The authorities dialog is included in the editor form:

<xi:include href="oxf:/xbl/nul/authorities-lookup/authorities-lookup.xbl" xxi:omit-xml-base="true"/>

The custom element and its reference to the VRA element it manages is declared for any field under authority control that should provide the dialog for entry. For example:

<nulAuthLkup:authorities-lookup authtype="subject" ref="vra:term"/>

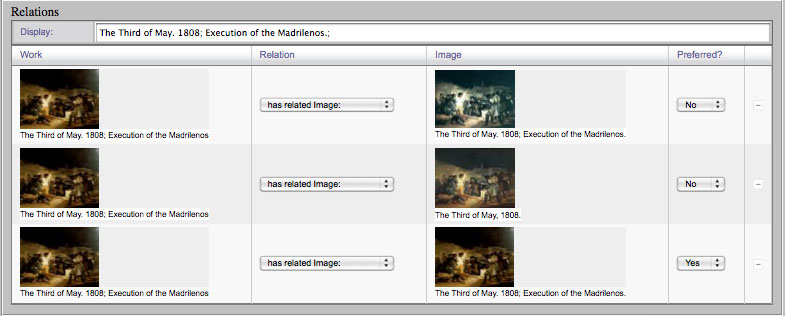

Search Integration

An important feature of VRA Core is its support for many-to-many Work / Image relationships. Having separate Work and Image records facilitates descriptive consistency and efficiency across images of the same work, while affording descriptive differentiation where needed for different views of the work. Catalogers must be able to efficiently assert relationships between Work and Image records. The editor supports editing separate Work and Image records simultaneously. Work records receive full VRA cataloging using all of the VRA ‘sets’ grouped in separate tabbed panels. A separate Image record can be loaded in the ‘Image’ tab, displaying its variable resolution zoomable image along with its VRA Title, Description, Subject, and Relations sets. These sets are the only ones currently provided in an Image record, but additional sets can be easily added if needed.

Both Works and Images can assert relationships to multiple Image and Work records respectively. To do this one needs to be able to search the collection, select appropriate items, and assert their appropriate relationships. Having a search feature in the editor with access to the entire collection in the context of editing a specific record makes this possible. It also facilitates other useful operations that draw on the larger collection. The editor supports the following actions on search results:

- Add this Image to the currently editing Work record

- Add this Image’s primary Work record to the currently editing Image

- Edit this Image record

- Edit this Image’s primary Work record

- Clone this Image’s primary Work record and edit it

- Display this Image’s public view in a separate window

The “public view” mentioned above is the “read only” HTML dissemination of the image with zooming apparatus, full metadata, and thumbnails of its related images.

Relationships are edited in the Work and Image records’ VRA RelationshipSet. There is a widget for these shown below. Work and Image records in this display can also be selected for editing, cloning, or full public display.

Workflow and Repository Integration

Cataloging takes place in the larger context of ingest workflow and publication. Cataloging is, of course, just one aspect of collection management. Cataloging is embedded into the workflow process in two ways. Image items in the workflow system, which manages scanning jobs and their processing towards publication or fulfillment, include a link to the editor with the workflow item identifier and repository identifier as parameters. Catalogers can inspect their workflow task queues and jump directly to items loaded into the editor. When a workflow item identifier is available to the editor, the editor displays an additional “cataloged” button which the cataloger can use to notify the workflow system when the item’s cataloging is complete. The workflow system can then advance the item if cataloging was the only process pending for its publication or fulfillment. This way a “save” action isn’t overloaded with both saving and indicating that the item is ready. Catalogers may catalog (and save) an item over multiple edit sessions before it is deemed ready for publication.

The repository identifier is used to retrieve and store the VRA record in a Fedora repository. When records are saved, using the “save” button, they are forwarded to a JMS (Java Message Service) queue for ingest processing. That process takes care of updating the item with the new VRA Core metadata in Fedora.

Thoughts on this XForms experience

This VRA Core editor is Northwestern’s first use of XForms in application development. Northwestern came to XForms fairly recently, after somewhat unsatisfying experiences in building web-based database applications on other platforms and encouragement from the work at Virginia, Stanford, and Wisconsin. While each platform has its strengths and weaknesses, using non-XML platforms to implement non-trivial XML data models inevitably requires just that: a non-trivial data model to implement. If you’re supporting a relatively simple descriptive model, it’s reasonable to develop a web-form application in whatever platform seems expedient and then crosswalk that simple model to a standards-based XML schema for archiving or transmission. However, when you start to use more and more of any expressive schema, the development and maintenance complexity of your model software can increase a lot. You typically wind up either over-simplifying the model for expediency, codifying the full schema in custom software, or writing a general purpose XML editor. In the end none of these approaches are very palatable. XForms’ direct support for the target XML schema as the application data model removes all of that, and is one of the principal attractions of XForms. It’s true that the flip side of that trade-off is that your view – the form itself – is tightly bound to the specific schema you’re supporting. However, the bulk of the work in XForms development is in developing and arranging interface widgets – combinations of primitive interface elements that combine to address a complex descriptive task. Designing such widgets for reuse should make their deployment in forms supporting other schemas a relatively low-cost activity. The combination of widgets like those for VRA Sets, an authorities dialog, and a search widget will likely form the core functionality of a variety of item level collection management applications at Northwestern.

Another benefit in XForms development worth pointing out is the quality and responsiveness of the mailing lists. Technology principals from Orbeon frequent the ops-users list and have been very helpful and timely in their replies to questions.

Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS) and Text Encoding Initiative (TEI)

Recently, several institutions have implemented XForms applications to edit MODS metadata. As mentioned above, Stanford has been using an Orbeon XForms to create MODS records for over two years. The original MODS editor was inspired by MODS Editor developed by Michael Park at Brown University.[10] The original application was a single form that exposed the most basic set of MODS elements to users for metadata creation. Early attempts focused on creating a single form that could render all the MODS elements in a way that was universal for all projects. However, after analyzing the needs of several project managers, it was realized that creating a single MODS form for all collections was much harder than simply creating several variant MODS forms. With the migration to the Form Runner environment, much of the form creation process has been greatly streamlined, and a similar approach has recently been applied to forms used to also generate TEI records.

The process of developing a new form usually entails modifying an existing form to have the structure outlined by the project manager’s requests. Default value lists, section labels, and field data types are all specified by the project manager. These specifications are then applied to a generalized MODS form and deployed on the server as its own form in the Orbeon application. Overall, the creation of individual forms for each collection goes very smoothly, since most collections’ MODS metadata are similar in overall structure. The differences tend to be found in the value constrained lists, default values, and editable/non-editable fields.

Very often, collections already have some metadata created, although this can be in a wide variety of forms and conditions. For example, some collections have MARC records already created in the university’s integrated library system, while other collections have records stored in FileMaker Pro databases. For these collections, often an export is converted to MODS and pre-populated into the eXist database. End-users are then able to go through the records in order to clean up or enrich the metadata. In this type of situation, XForms really shows some of its advantages since it stores XML in a server-side DOM object rather than in a client-side Javascript object. When metadata already exists for a collection, often it is for cataloged items sent to the Stanford scanning labs. In these situations, the bulk of the record does not need to be changed, since only a few elements (such as a URL or an updated copyright notice) are added. Exposing the entire record in a form can be overkill, especially if a large part of an item’s MODS is collection-level boilerplate. Using most standard web application languages, this can be problematic, since standard HTML forms do not have an MVC. In Orbeon, it’s possible to only show a small subset of the MODS and hide the rest of the XML. When the XML is edited and submitted to the datastore, the entire XML document is sent. Since all this is done by the core Orbeon application, developers do not have to resort to scripting AJAX functions to handle XML manipulation. Like the Northwestern’s VRA Core application, the Stanford Metadata Toolkit also uses XBL to bind a form’s MVC to third-party web services. One of the most helpful features the toolkit provides is the ability to import MODS records from the university’s ILMS. By keying on particular MODS identifiers, this service pulls a MARC record from an instance of SirsiDynix Symphony, converts it to MODS using the Library of Congress MARCXML to MODS stylesheet, then populates the form. The way Orbeon’s MVC operates is important for facilitating the desired behavior. Since a core part of the model is simply the MODS schema, the form does not have to declare all the possible elements that are present in the MODS record. When the form loads a new MODS record, defined elements will just populate the form as described in the view, but the rest of the XML structure will persist as loaded in the DOM object. This keeps developers from having to explicitly declare all the possible elements in a MODS document in order to ensure imported XML data does not break their MVC or is lost.

Overall, this ability to handle complicated XML structures is XForms’ biggest asset. In the past, attempts to develop similar applications required either breaking the XML into smaller chunks, a strong reliance on customized client-side AJAX, or both. In the Metadata Toolkit, the application is allowed to interact with the data with an XML-based approach. In XForms, the challenge usually comes in attempting to sort out the particulars of how the view represents your model, which can be difficult considering most schemas are not developed with data entry in mind. However, while the learning curve can be steep, it does free the developer up from having to jump through hoops to build a language-specific model that is replacing an XML schema.

IV. Enterprise Integration

Once your XForms are up and working, and your metadata librarians are happily creating metadata, what do you do with the metadata they create? Fortunately, handling XForms output is surprisingly simple, as all that is produced is a stream of XML that can be POSTed or PUT via HTTP requests (REST or SOAP) to any web service that is set up to process incoming streams. The XForms submission methods are considerably richer than standard HTML form submission elements; submissions can be chained together, the same XML stream can be sent off in parallel to different endpoints, submissions can happen behind the scenes as users type (as is the case with the autosuggest functions, mentioned above), and submission widgets (buttons, etc.) can be activated/deactivated depending on the validity of the data entered into the form, or other criteria.

Orbeon ships with an embedded eXist[11] XML database. In its samples and tutorials, data is PUT in the database via a RESTful request. Then metadata can be retrieved when the form loads, and the fields can be pre-populated, via a GET request to the database. In a production environment where manually creating or editing metadata is a piece of a larger workflow, endpoints will vary: data can be sent to a Fedora repository to update a datastream, sent to DSpace, become part of an ILS catalog record, and so on. With the introduction of Form Runner, the use of an application-wide persistence layer allows the forms to seamlessly interact with different datastores. By default, Orbeon CE Form Runner uses the embedded eXist database, although it also ships with a persistence layer that is configured for a MySQL database. Orbeon Professional Edition ships with both Oracle integration, as well as a persistence layer configured for the Alfresco content management system.

One approach currently being investigated is developing a persistence layer for a Fedora repository. Fedora offers some interesting possibilities, since it would be able to utilize the versioning, optimistic locking, and messaging for both the metadata and form markups. At Stanford, initial development integration has utilized a middleware application written in Sinatra that brokers communication between Orbeon and Fedora. This was done in order to more seamlessly integrate the Stanford unique identifier and workflow services. In this approach, a form’s markup is stored in the Fedora repository as its own object. A particular collection that utilizes this form is given relationships in Fedora’s REL-EXT that ties the form object to collection object. The collection objects also have relationships to their member items. This allows an application to automatically pull a particular collection item’s form from Fedora, as well as generate lists of items related to a particular form or collection. Since the application uses the Stanford workflow service, it is also possible to generate collection or form-based queues on workflow status.

The Fedora work also allows developers to take advantage of the efforts being made by the Fedora community to incorporate the Fedora Security Layer (FeSL).[12] The Orbeon application does offer a standard authentication mechanism provided by any J2EE application server, but this can be difficult to integrate into a large organizational authentication strategy. At Stanford, currently the web application is behind a web authentication layer that only allows access to whitelisted users. However, authentication has not yet been fully incorporated into the application. For example, from the datastore’s perspective all records are made by a single user that is held by the application. By using FeSL, access control would be able to be set at the Fedora object level, which would not only make for better security policy, but also allow separate applications to share common access control decisions.

Another promising avenue some of the authors have been exploring is integrating XForms into a workflow designed around an Enterprise Service Bus. In this case, XML streams are sent as “messages” to the bus, where they are then processed and kicked out for further processing and storage according to rules and paths defined in the bus. One important consideration that has become clear to the authors is the need to distinguish between data in an unfinished state, and data that is ready for further processing and storage. In that regard, eXist or some other XML database can be useful in a production environment as a temporary storage area, a buffer where metadata that is in the process of being created can be stored and updated, before it is marked as ready to move on. Using an intermediary buffer for editing metadata can offset some of the problems with updating “live” data, insofar as a working copy is made from live data, the working copy is modifiable offline, and when it is deemed ready to go live, it is copied back into the “live” location. Issues of locking and simultaneous edits must be addressed, however, as should questions of authorization.

V. Conclusion

Despite its power and flexibility, XForms has yet to become a mainstream standard. This is mostly due to its unfamiliarity, as it is a standard that has not received much attention in the web development community. Of those who have had an opportunity to explore the technology, some have raised objections to it. The objections to XForms can be boiled down to the following three points:

- It is a dying (or dead) standard, with little support.

- It is difficult and complex.

- The infrastructure necessary to process XForms adds extra support overhead to your workflow environment.

The first point has been addressed above: the standard itself is alive and well, and despite the lack of native support for it in browsers, there is a small but active and growing community of developers who have adopted the standard, and a variety of open source and vendor applications under active development that process XForms. Many large enterprises and public institutions across the world have adopted XForms for building forms, for example: The National Archives and Records Administration, Cisco, Pfizer, and the University of California Santa Barbara.[13]

Regarding the second objection, a perceived weaknesses of XForms which has lead to reluctance to adopt the standard and commit to building applications around it is that libraries lack personnel who are experienced with it. Certainly many libraries have committed to PHP, Perl, and Ruby on Rails development and, in some cases, have been developing applications based on those languages for more than a decade. However, many libraries already have potential XForms developers. As mentioned above, XSLT programmers with a concept of the Document Object Model and XPath would have little trouble adapting to XForms development. There are numerous resources for XForms development online, including the great support community surrounding Orbeon. With many institutions moving progressively toward open source releases of software applications, this will save time, money, and effort for many libraries that intend to create metadata records. The Brown University MODS editor, the Stanford MODS editor and the University of Virginia EAD editor are freely available, for example, and the Northwestern University VRA Core editor will be available in the future. Once the structures of the XForms documents are understood, designers can tweak the model and view, and begin to integrate the application into current workflows, rather than starting from scratch to build something completely new. XForms are certainly non-trivial to master, but its difficulty must be evaluated in the context of your entire application environment and support of the software that underlies it. There are many individuals and organizations throughout the Library, Archive, and Museum communities that are involved in cutting-edge tool development; the wheel certainly could be re-invented, and applications that fill the same purposes as XForms could be developed and implemented using the language du jour, be it Ruby, Java, Perl, Groovy, LISP, or what-have-you. However, one should be mindful of the long-term maintainability of such projects. A metadata editor built in a Ruby on Rails or PHP framework with a lot of javascript attached may be able to generate the same MODS data model as an XForms-based editor. The difference is that the XForms developer is mostly concerned with writing solely XForms XML. The server-side processor includes the javascript necessary to effectively render and validate the form in the browser. In XForms, the data model is seamlessly bound to the interface (inputs) and to the data serialization (output), removing layers of programmatic abstraction that require ongoing maintenance (serializations of data objects in the model to the desired format, updates to the objects and backend object storage whenever the model is changed, etc.) This means that the XForms application can be more easily migrated to new platforms or upgraded to newer versions of the processor, as it is primarily XML, with little or no storage and language dependencies, beyond the ones bound with the back-end processor. A Rails application with a great deal of highly customized javascript may not function as desired five or ten years from now, which requires developers to maintain it regularly in the long-term.

The third point of criticism listed above is the perception that XForms complicates the application stack and convolutes the cyber-infrastructure with yet another platform that systems administrators have to manage. As mentioned previously in this paper, Orbeon runs in Apache Tomcat. So does Chiba, another open source server-side XForms processor (which does not have the same market share or support base as Orbeon).[14] Fedora and Solr, two potential building blocks for contemporary institutional repositories, also function in a Tomcat production environment. In this case, using XForms with Orbeon as opposed to a Rails or PHP application for depositing digital materials into a repository actually simplifies the infrastructure, rather than complicating it.

One of the main benefits of XForms is the facility with which you can leverage the work others have done to implement forms that can then in turn be shared within a wider community of users outside the walls of your own library. In this respect, the potential disadvantage of introducing another application layer into your workflow environment can become an advantage, as it helps to keep your forms and metadata serializations loosely coupled with the other pieces of your environment. More importantly, it offers you the opportunity to participate in an active and growing community of XForms developers working to solve the same problems that confront you. In this sense, as the authors of this paper have discovered, the true power of XForms is in its community; working together, they have solved problems more efficiently and rapidly than any of them could have done on their own.

Given the sustainability of the standard and the ability to create and edit complex XML models, XForms has great potential for the library community. Not only can input forms and XML serializations be created with XForms, but applications can be woven into digitization and publication workflows, controlled vocabularies can be managed, and web services commonly used in libraries can be easily hooked to the forms. With numerous institutions exploring the standard, XForms holds promise for becoming a mainstream form of application development over the next several years.

References

[1] Bruce, Thomas and Dianne Hillman. “The Continuum of Metadata Quality: Defining, Expressing, Exploiting.” Metadata in Practice. ALA Editions, 2004.

(COinS)

[2] Dublin Core: http://dublincore.org/ Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS): http://www.loc.gov/standards/mods/ Text Encoding Initiative (TEI): http://www.tei-c.org/index.xml Encoded Archival Description (EAD): http://www.loc.gov/ead/ VRA Core: http://www.vraweb.org/projects/vracore4/

[3] http://www.w3.org/TR/xforms11/. IBM continues to play a large role in maintenance and support of the standard. Ubiquity XForms (http://code.google.com/p/ubiquity-xforms/) is a javascript library that plugs into existing javascript APIs for browser-based XForms rendering.

[4] For more information on Representational State Transfer (REST), see http://www.ics.uci.edu/~fielding/pubs/dissertation/top.htm; for information on Simple Object Access Protocol, see http://www.w3.org/TR/soap/.

[5] Recent history of XHTML and HTML5 and XForms: http://diveintohtml5.org/past.html

[6] XForms Software catalog: http://www.w3.org/MarkUp/Forms/wiki/XForms_Implementations

[7] Orbeon Download: http://orbeon.com/forms/download

[8] VOrbeon Form Runner: http://www.orbeon.com/forms/orbeon-form-runner

[9] See: http://code.google.com/p/eaditor/

[10] Brown MODS Editor: http://library.brown.edu/its/software/metadata/

[11] http://exist.sourceforge.net/

[12] Fedora Security Layer: https://wiki.duraspace.org/display/FCR30/Fedora+Security+Layer+%28FeSL%29

[13] http://www.orbeon.com/company/customers

[14] http://chiba.sourceforge.net/

About the Authors

Ethan Gruber: Ethan is a Web Application Developer in the Scholars’ Lab of the University of Virginia Library. He specializes in creation and delivery of cultural heritage digital content, including metadata modeling and information architecture. His website is http://people.virginia.edu/~ewg4x/

Chris Fitzpatrick: Chris is a developer at the Stanford University Digital Library Systems and Services group. He is a graduate of Portland State University, as well as San Jose State University’s MLIS program. He enjoys programming in both Ruby on Rails and XForms. His blog can be read at http://worldonawire.info/.

Bill Parod: Bill is a software developer at Northwestern University Library. He helps design and implement systems for managing and delivering digital collections. His previous work includes software development in text analysis, aerospace, and the coin-op game industry.

Scott Prater: Scott is a digital library applications developer and project manager at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. He currently specializes in designing and implementing software infrastructures for digital collections. He has worked as a gold miner and system administrator, among other professions, in past lives. His work website is: http://sdg.library.wisc.edu/.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply