By Kathleen Bauer, Michael Friscia, and Scott Matheson

Ubiquitous smart phone and mobile device use has raised a new opportunity for libraries. Current mobile options provide patrons with better access both physical and virtual library resources. The handheld, portable smart phone is a perfect technology to help patrons discover material online and then successfully navigate physical stacks locations. Libraries have begun to use this technology, offering views of their online catalogs optimized for mobile access, mobile tours of libraries and QR codes as ways to connect patrons to their physical libraries. Notable examples include the New York Public Library (www.nypl.org/mobile-help) and North Carolina State University (http://www.lib.ncsu.edu/dli/projects/librariesmobile/). Maps are an obvious match for mobile development because a person can easily use a map on a handheld device to guide them through streets, or for that matter the shelves in a library. At Yale University Library (YUL) it was apparent from recorded reference transactions that, after finding a book in the catalog, patrons had difficulty knowing how to use the call number to find the book on the shelf. Library staff realized that the logic of the call number lent itself to a computer algorithm to help locate sets of call numbers, and that linking call number maps of the library’s stacks from the online catalog would be an effective mobile service to offer patrons. Given any call number of a book in Sterling Memorial Library at YUL, a map will be displayed which highlights that call number’s general area on a floor in the stacks. YUL introduced the mapping application in Yufind, a catalog in place at Yale since 2008 which is based on the Vufind catalog developed at Villanova [1]. The maps are linked from each record in the Yufind catalog and the legacy Voyager catalog (called Orbis), and also from an iPad kiosk, where a patron can enter a call number and access the same maps. The mapping applications have helped reduce the number of questions about finding call numbers at the Sterling Memorial Library Information Desk by 20.6%. This article describes how maps were designed, the logic behind the application, use of YUL’s classification system, and how the algorithm was built using a web application that accepts RESTful URLs and an SQL database that stores relational data about the book locations, call numbers and maps.

Background

Mobile Technology

Mobile technology has become ubiquitous in the college-age population: according to some surveys, close to 100% of undergraduate students worldwide use at least one smart phone or other mobile device such as the iPad, with the highest use occurring in North America. [2] [3] Given the popularity and growth of mobile and smart phone technology, universities will increasingly make a priority to incorporate mobile computing into academic life(Educause Horizon Report 2011). Efforts to simply put web pages onto a mobile device do not work well, as text or image-heavy pages may not make sense on a mobile device, and some services are not well-suited to mobile access. Mapping applications do work well for mobile computing, as a handheld device and an online interactive map are a great way to find your way in unfamiliar surroundings. It is therefore not surprising that maps have been used widely on smart phones for years.

Setting: At YUL reference transactions revealed that patrons had a need for directional information in the library, especially to find books. In fall 2010, 7.3% of all questions at the Sterling Info Desk dealt with finding a particular call number. A number of factors contributed to the problem: signage was poor or nonexistent, some parts of the collection were tucked away in small reading rooms, and two call number systems (Library of Congress and Yale Classification) added to general confusion. A patron who found a record in the online catalog would know the library (Yale has eighteen) and the call number but no information that would help the patron decode the call number to find it on the shelf (there are 15 floors of stacks in the largest library). For the reasons discussed above, library staff knew that maps would be a good application to present both on the regular web and on mobile devices, and the library’s Yufind catalog seemed a perfect place to experiment with linked maps.

Library Classification: Books at Yale University Library (YUL) are mainly arranged on shelves according to the Library of Congress (LC) classification system. LC classification builds on the work of Melvyl Dewey, who created a system using base ten mathematics to cover all the world’s ideas. He first divided knowledge into ten general classes, and then each of those into ten more classes, giving one hundred total classes and so on, always subdividing by ten, as described in the 1876 work A Classification and Subject Index for Cataloguing and Arranging Books and Pamphlets of a Library [4]. Dewey extolled the simplicity of his system, and also claimed that it would allow books in a topic to be generally kept together in a library, aiding any patron wishing to discover material by simply browsing a section in the library. The Library of Congress created a different system using letters instead of numbers to signify broad topical areas [5]. For example in LC classification, B denotes material in Philosophy, Psychology, and Religion, while both E and F cover works in American History. LC is North American-centric (hence two categories for history of Americas, but one class D for all the rest of the world). All of Science is in one category Q, but Military and Naval Science each has its own class, U and V respectively. There is a well-developed literature on the strengths, weaknesses and cultural biases of various classification schemes [6] and a full discussion is outside the scope of this article.

In addition to LC classification, a YUL-developed Yale classification system was used until 1970. While no new books are given a call number using Yale classification, older materials remain in the collection with their original Yale class call numbers. In addition the large YUL system involves many buildings and special collection locations which must be evaluated along with call numbers to determine actual locations. Even taking into account the two classification schema and numerous YUL locations it is still fairly straightforward to follow a set of rules in sequential order to decode any call number for a book in the Yale Library system and determine its general physical location. Further these rules are easily translated into a computer algorithm. This ability was used in the project described here to help the patron move from a call number in the online catalog, to the correct map of that books floor location, and to the appropriate section of that floor, all through the use of its assigned call number (both LC and Yale).

Building the Application

A project was started with these goals:

- Produce physical and online maps for every stack floor in the Sterling Memorial Library (SML), 15 floors total.

- Provide links from every Yufind record to the correct map in SML or to a general map of separate library locations external to SML.

- Highlight the general area of a call number on each floor map.

- Build an iPad kiosk where a user could enter a call number and find the correct map.

- Develop the framework to accommodate, at least at a high-level, other classification and shelfmark schemes used in the Yale system, including SuDocs, Hicks and accession number-based collection items.

Maps and Supporting Tables

A graduate student in Art History was hired to create maps for every floor in the library. The implementation team worked from maps used by staff which indicated call number ranges in the stacks. Early in the project a decision needed to be made about how precise the maps should be in depicting call number ranges. A very precise approach would have tried to locate the specific shelf holding a book. A very imprecise but simple approach would have shown the floor for the book with no details about call number sections within the floor. A medium approach was chosen for this project, in which fairly large sections within a floor are shown with their call number ranges. The fifteen stack floors in Sterling were produced in Adobe Illustrator, with each stack range included, along with elevators, bathrooms, computers, and exits. Each level has a unique color associated with it, and that color is used on the print map and the directory for that floor. The same maps used online are posted on each floor in at least two areas near main elevators. This provides a consistent experience for the patron as they move from online to orienting themselves in the physical space.

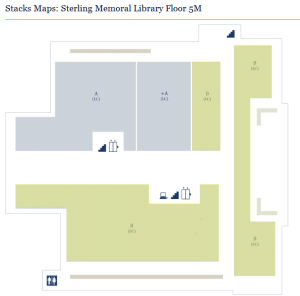

In practice only information found before the period or decimal point in call numbers were used in creating the maps and linking algorithm. In some cases only the first letter was used along with information about whether a book is oversize or not (indicated by a plus sign). In the case of the floor 5M (Figure 1), only the first letter is used because relatively small numbers of books are found in these ranges, so a single range may have material for BA, BC, BD and so on. When the letter part changed so frequently there seemed little point in trying to show these changes on a map, and the relative locations would frequently change due to changes in the collection. Thus not much information is used beyond that the floor is 5M and the location of “A” call numbers versus “B” call numbers.

Figure 1. Floor 5M in Sterling Memorial Library showing very large blocks of call number ranges. The plus sign (+) indicates oversize.

Maps for other floors contain more detailed information and use more than the first letter of call numbers. A more typical map is shown in Figure 2. This map provides more information within the P class, using the second letter following the first P. By using large chunks of areas the maps do no not need to be updated frequently when small shifts occur among the shelves (as material is added or moved). The “chunking” approach aims to get the patron close enough to use the call number guides found on the end of every range of shelves.

Figure 2. Map for Floor 1MB shows blocks for smaller call number ranges, with the range PS highlighted.

SQL tables contain information for each map necessary for the correct functioning of the online application. In the StackMap table every call number box is assigned an arbitrary identifying number and the file name and location for the corresponding floor map image. For example in the map in Figure 2, there are seven boxes, and the PT-PZ box might be internally labeled number 2. That box 2 is then linked to all the call number ranges in it, from the “smallest” call number to the largest thusly: PT0000 to PT99999, PU0000 to PU99999, PV0000 to PV0000, PW0000 to PW9999, PX0000 to PX9999, PY0000 to PY9999 and PZ0000 to PZ9999, even though there may not be any books currently in some of these ranges, every eventual possibility is covered. Numbers and letters after the decimal are ignored.

When a call number is within a box, the block should be highlighted. To do this each block is broken into rectangles, and the coordinates of the upper left and lower right part of each rectangle in the box are also recorded in a separate table, StackMap_coordinate. There are some blocks that require more than one rectangle to be drawn because the stacks for that call number range are L shaped or spread out in different areas of a floor. This is why the StackMap table does not store coordinates since there is a one-to-many relationship with the StackMap_coordinates table.

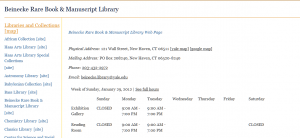

With this information any call number of a book in Sterling Memorial Library can be matched to the appropriate map and box, and that map will display highlighting the correct box. For books in other libraries, two other SQL tables are needed. One stores all the individual location codes used in the library catalog, e.g., “BEINECKE (Non-Circulating)” paired with the library that contains that location, e.g., “Beinecke”. The second table links libraries to URLs for those libraries. Generally these pages list the address of the library, hours of operation and contact information, as in the example in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The page linked for call numbers of items in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, a library without open stacks and no associated stack maps.

The Algorithm

The application that selects the correct map location given a call number consists of two parts: a web application that accepts RESTful URLs and an SQL database that stores some relational data. The web application was written in C# and consists of a single class containing the algorithm. The main file, default.aspx displays an image GIF file showing the map of the floor the item is on and CSS is used to place a DIV over the map which highlights (25% opacity) the matching call number box. The map image is still fully visible under the highlighting. The SQL database uses four relational tables (explained above in Maps and Supporting Tables) that store information about which GIF image to use, which areas to highlight and in cases where the location is not associated with a map, a URL to provide more information about the library location where the materials are held.

Two key arguments are needed in the web application: the location code of the item from the OPAC and the call number. The URL is received and the arguments are processed by the algorithm. There are just a few vital pieces of information needed to make the application work. First, it must determine whether the call number uses Yale or LC classification. There are some cases in which the Yale and LC classifications overlap making it impossible to tell them apart. Additionally many classifications are held in various libraries at Yale. Luckily this information is included in the location code; and therefore this code is examined first. If the location fails to identify the classification, then regular expressions are used to determine it. The algorithm checks for special cases such as oversized items and folios, which may be indicated by special characters or keywords in the call number. With the classification scheme, oversize information, and the first letters and numbers of the call number it is possible to determine which map the call number belongs to. At this point most of the work is sent to the SQL tables to figure out where the system thinks the item is located. Exceptions to be handled include temporary shelving of materials, e.g., course reserve items or other special circumstances, which can be determined by the location code.

The first query run will return a list of library locations, floors and the map sections for where the item is located. For example the following may be returned for an item: SML, 1MB, 1. Where SML is the building code for the library, 1MB is the floor and 1 is the boxed section of the map containing the call number. The first two set the name of the map file to be used. In this case the file is named sml_1mb.gif. The box number 1 indicates the area that will be highlighted on the map. The highlighted boxes are drawn using HTML DIV tags with absolute CSS placement. The StackMap_coordinate SQL table links a map section ID with the top, left, width and height of the DIV(s) to be drawn.

When the call number lookup fails to find an associated map to display or when a map exists but the call number range does not fall onto the map stored, the patron is redirected to a URL with additional information. In the worst case, where the location is not recognized, the patron will be redirected to the entire list of all Yale library locations.

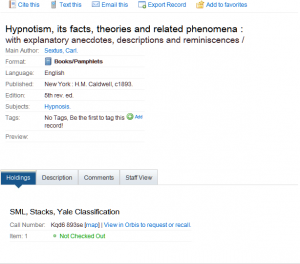

Putting Call Number Maps into Yufind and Orbis

The project team needed to decide where in the Yufind catalog links to maps would be displayed. At the title display level, maps could not be displayed because a single title may be held in several locations. The more logical place was to display the link to maps was from the item level, where only one location is possible. Once this was determined it was simply a matter of adding code to the Yufind bibliographic display template to build a call to the mapping web service. This meant building a URL that contained the location name and the call number, properly encoded. We experienced a small glitch due to the different ways that Solaris/PHP Yufind code encoded the URL and the way that the Windows/.NET web service decoded the URL on the receiving end. Once we identified this problem, we were able to code around it.

Once the implementation was done in Yufind and had been well tested, it was simple enough to add the same link to the library’s legacy Voyager online public access catalog (OPAC). Because there was no logic required on the OPAC side and the information needed by the web service was included in the bibliographic display, it was easy to replicate the simple link created in Yufind.

After initial testing, we decided to also pass the unique record number of the item to the mapping service so that we can display a link back to the catalog. This allows patrons to request staff paging of an item if they decide not to follow the map and retrieve the book themselves.

The web service call, including location, callnumber and bibID parameters, looks like this:

Note the simple URLencode of the existing human-readable location code and call number. Because the web service handles these parameters, deployment to different catalog systems is simplified.

We chose to have the map display in a new window for the basic rollout for both Yufind and Orbis, but as we move to a more mobile-optimized display, we will revisit the exact mechanics of the display.

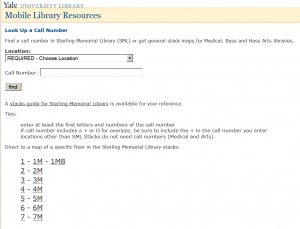

iPad Kiosk

Finally, to create the kiosk for patrons who had written down a location and call number and were in the Sterling Memorial Library but weren’t sure which floor to go to, we coded a simple web form. Since the web service depends on perfectly formatted location names for choosing between the Yale and LC class schemes, we created a drop-down that requires a patron to identify the scheme, based on the location they have written down. Patrons must enter “at least the first letters and numbers” of the call number in a text entry box, and this completes the form. The lookup is available at http://www.library.yale.edu/m/call.html

Results

In the fall semester 2010, 7.3% of all questions at the Information Desk at Sterling Memorial Library were questions relating to finding a specific call number. After the mapping project was fully implemented in fall 2011 the number of call number related questions was reduced to 5.8% of all questions at the same desk, a 20.6% reduction in patron inquiries on this topic. More publicity for the mapping functionality and the iPad kiosk should further help reduce the number of requests. Based solely on the reduction in requests for help finding call numbers in Sterling Memorial Library the improved mapping can be judged successful and worth replicating elsewhere in the Yale Library system.

Future directions

The first extension of this project will be to map all collection areas in the Yale Library and provide location links for all of them in the library’s catalog. Future development will include using the same lookup for other types of resources such as reading rooms, special collections and restrooms outside of the stacks areas. The call number maps will also be used to help students find work carrels near their subject areas, something students have told us they want. Finally, staff are interested in reversing this project, providing QR codes near call number ranges which will lead patrons to virtual shelf browsing in the catalog, another feature patrons have requested. This project has opened new possibilities in exploiting data which help to link the online world and the physical in new and interesting ways and we imagine that more ways to use this functionality will become apparent as we investigate mobile technologies.

Code

Notes

[1] Houser J. 2009. The VuFind implementation at Villanova University. Library Hi Tech 27(1):93-105.

[2] Cummings J, Merrill A, Borrelli S. 2010. The use of handheld mobile devices: Their impact and implications for library services. Library Hi Tech 28(1):22-40.

[3] GSM. 2011. Mobile phone usage report 2011: The things you do. http://www.gsmarena.com/mobile_phone_usage_survey-review-592.php

[4] Dewey M, Comaromi JP, Beall J, Matthews WE, New GR, Forest Press. 1989. Dewey decimal classification and relative index. Albany, N.Y.: Forest Press, a division of OCLC Online Computer Library Center.

[5] Taylor AG. 1999. The organization of information. Englewood, Colo.: Libraries Unlimited.

[6] Mai JE 2010. Classification in a social world: bias and trust. Journal of Documentation 66(5):627-642.

About the Authors

Kathleen Bauer is the Director of Usability and Assessment at Yale University Library, a department she created. She is currently a doctoral student at Simmons College, has an MS in Mathematics from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and a BA from Mount Holyoke College. For more information about Usability and Assessment at Yale see http://www.library.yale.edu/usability.

Michael Friscia is the Manager of Digital Library and Programming Services at Yale University Library. His department focuses on the library website, interfaces and digital asset management. Michael is the lead programmer for Ladybird, a new tool at Yale University Library that’s being developed to centralize digitization workflows, integrate with digital preservation systems and route digital objects to discovery interfaces. He can be contacted at Michael.Friscia@yale.edu.

Scott Matheson is Librarian for Digital Resources at Yale Law Library. He has experience in public services and in library IT where he was web manager at Yale University Library. He has a MLIS and a JD from the University of Washington. He can be contacted at scott.matheson@yale.edu.

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply