by Joann Ransom with Chris Cormack and Rosalie Blake

Introduction

Look at it from our point of view:

We were a very ordinary public library in New Zealand, we had hardly any money and a library management system that was going to stop working on 1st January 2000 . . . . What else could we have done? And how hard could it be anyway? The librarians would tell the programmers how a library works and they would make it so. And we weren’t going to make a big deal of this, ok; 3 months is loads of time.

And thus Koha was born . . . ok, not quite but pretty much. From time to time over the years, we have been asked how Koha got started, because it is pretty big now, so here is our story.

Context

Horowhenua District is a one hour drive north of Wellington, the capital city of New Zealand. It is medium in almost every way you can think of. It is of medium population–30,000. It is on the low side of medium in terms of socio-economic status. The district has one medium-sized town, three small towns and a collection of villages and beach settlements. There are libraries in three towns, as well as a tiny volunteer library. The libraries are heavily used and well loved by their community, functioning very much like community centres.

But medium does not mean ordinary. In 1996, the Horowhenua District Council established the Horowhenua Library Trust (HLT) and settled on the Trust all the assets of the libraries, except the buildings. From 1 January 1997, the Trust would run the libraries. A fixed budget meant the Trust could only seek additional funding from Council for exceptional circumstances. The move away from the local authority environment allowed a quite different culture to develop in Horowhenua libraries. We experienced freedom to explore alternate avenues, to innovate, to take risks in ways that would have been difficult under the direct control of a district council. Being medium is an asset here. We’re large enough to reach a critical mass, but not important enough for everyone to be watching every move we make.

Rosalie Blake was appointed Head of Libraries for the HLT in 1997. She developed a culture within the District Libraries of open communication and consensual decision making where everyone is encouraged to help solve problems, no matter what their status in the organisation. The Trustees [1] also influenced the organisational culture. In 1999 we had 5 individuals with strong community and business backgrounds who were willing to take calculated risks in order to maximise gains.

Our partner in this venture was Katipo Communications, a web development firm based in Wellington, New Zealand, with whom we already had a long and trusted relationship. Rachel Hamilton-Williams started the company in September 1996, and by January 1997 had hired her first programmer, Chris Cormack. Since then Katipo has continued to grow both in numbers and skills, servicing clients throughout New Zealand and the world. HLT still works very closely with Katipo, a business relationship spanning over 12 years.

The Situation

In 1998 the Trust undertook a complete review of all library activities. The report, Towards Superior Service [2], included in-depth focus group interviews of patrons. Our patrons made it clear that while they appreciated that computers were a necessary part of a modern library, they did not consider them the most important part. Our patrons did not want to see a deterioration of traditional library services (books to borrow, pleasant spaces to sit and browse) in favour of IT development, and they did not want new charges imposed to fund sophisticated computer gear. If it came to a contest between the library as a provider of information through technological development, and the library as a community centre which is safe, comfortable and "has the walls lined with books", the people preferred the latter. If we needed to fund new technology, this was a strong warning not to dip into the book budget.

In 1999 with a 12 year-old system running on a 386 server, HLT needed to think replacement. While our much-loved DOS system still performed very adequately, it looked old-fashioned and somewhat tired. The crunch, however, was that while the system would probably survive Y2K, we were sure our networking would not. We asked Council for an exceptional circumstances grant, and were successful in getting agreement for Council to fund 50% of the cost of a replacement library system.

With our management contract with Council, we were on a fixed income and responsible for our own finances, which made us very conscious of costs. We had negotiated a favourable deal for the telecommunications link between our branch libraries and the district library, and we were very reluctant to change that.

The Open Source World

Open Source Software (OSS) is software in which both source code and binaries are distributed or accessible for a given product, usually for free. While "shareware" and "freeware" have been available since the earliest days of computing, OSS had developed in the years leading up to 2000 on a different scale entirely. It was no longer confined to the realm of "hobby" programmes. OSS projects were starting to produce software that matched or exceeded the quality of commercial products at the time, and Linux was starting to challenge Windows in very large-scale projects.

Objectives

Our overall objective was to source a library system which:

- could be installed before Y2K complications immobilised us,

- was economical, in terms of both initial purchase and future license and maintenance support fees,

- ran effectively and fast by dial-up modem on an ordinary telephone line,

- used up-to-the minute technologies, looked good, and was easy for both staff and public to use,

- took advantage of new technology to permit members to access our catalogue and their own records from home, and

- let us link easily to other sources of information – other databases and the Internet.

If we could achieve all of these objectives, we’d be well on the way to an excellent service.

A Beginning

We started, traditionally enough, by sending a Request for a Proposal (RFP) to suppliers of library systems. Our initial RFP explored the possibility of a joint development in co-operation with our southern neighbours, Kapiti Coast District Libraries. This was an idea worth exploring, but the cost of communication links rendered the joint system prohibitively expensive, and we reluctantly went our separate ways.

Examination of the proposals revealed:

- there are systems available that over-deliver, at a cost considerably higher than we wanted to pay,

- the systems which we could afford met only some of our needs,

- all the available systems had much more expensive communications solutions than we had been using and most had higher maintenance charges.

There simply was no off-the-shelf package that met all our objectives.

In commenting on the proposals we received, Katipo staff observed that it was a pity none of the available systems used Internet technology, since that would take care of the communications speed and costs. Did such a system exist? We hunted, and found fragments, and work in progress, but no system that would fit us. "How hard can it be" Katipo staff wondered, "to write a library system that uses Internet technology?" Well, not very, as it turned out.

Could We Write Our Own?

There were barely 15 weeks until D-Day. The proposal would develop systems that used WWW protocols, which was pretty radical at the time, and for which development was significantly easier and faster than under Windows (which was the favoured platform for commercial library system providers). Could Katipo deliver in time? Although primarily web designers, Katipo had already done lots of database work and an OPAC for Wellington City Library. It looked do-able, but it would be tight.

Katipo had an excellent reputation for attractive, workable web pages for a variety of clients. The brief was that if you could use a web browser, you’d be able to use a library programme which used web technology. The issue of providing external access was no problem at all—that’s what the World Wide Web was all about.

The system would be released under the GNU General Public License (GPL) [3], ensuring that the library system we were commissioning would be free/open source software. This was suggested by Katipo as a way to ensure the project had longevity; they didn’t necessarily want to spend the rest of their days supporting a proprietary system. Koha would thus be available to anyone who wanted to try it and had the technical expertise to implement it. We would encourage other people to use it—because they would improve and enhance it, add to it, fix it and join it up with other good programmes. The GPL would ensure that subsequent modifications and additions by other organisations were open source as well.

Demonstrating the difference between the Trust environment and the local authority environment appealed to us. This project had the potential for establishing a reputation for the HLT as innovators, people who put library priorities in the right order, listened to their patrons and acted upon what they heard. Our patrons told us that spending large sums on computers was not their top priority. Libraries are IT organisations, but we don’t have to buy into high-cost solutions. No-frills efficiency and co-operative development may produce far more in the long run, not just for Horowhenua, but for other libraries as well. The undeniable fact that an open-source library system is a public good was not lost on us.

A significant part of the cost of commercial library systems is license fees for other commercial software used as components in that system—e.g. the cost of development tools used in the construction of the system, and ongoing license costs for other software not necessarily written by the library system provider (database systems, remote control systems, operating systems). Only a portion of the cost of a commercial library system is for code actually written by the library system company.

The new system we were thinking about would have two interfaces—a web browser for most purposes, but a simple, fast Telnet interface for issues and returns, especially at the branches. The software Katipo used to build the new library system was already well proven. It was FLOSS software so as well as the benefits of being fast and robust it came with all the freedoms that we were seeking: Debian/GNU Linux as the operating system, Perl as the programming language and MySQL as the relational database.

Regarding equipment purchases, Katipo had a reassuring "let’s-try-the-old-ones-and-see" attitude, before they sent us out to order new PCs for every staff member. There was a potential saving if we didn’t have to buy all new machinery.

The Trustees invited Katipo to prepare a quote, and it was acceptable.

The Name

We struggled with a name for our developing programme before deciding on Koha. Koha is a Maori word from the native people of New Zealand meaning gift or donation—or perhaps more like “giving your specialty to the collective event”. There is a sense of quid pro quo or reciprocation about the concept, too. In traditional Maori society (and still) you bring a koha (contribution) to an event like a funeral or wedding or big meeting, often food or the specialty of your region. When it’s your turn to hold an event all your guests will bring a koha, to ease the burden of catering for a lot of people. We chose Koha as the name, because it’s free and because it’s our gift to the world.

Figure 1: Koha Logos

The Development Process

The proposed method was prototyping, rather than designing. It started with a fast analysis of what the present system did, and of what we would like it to do. It was the responsibility of HLT staff to ensure the software writers did not miss any key points in their fundamental understanding of the way libraries work. A rudimentary first cut was written quickly and presented, tested, then fixed, rewritten and tested again. Librarians tested, explained, clarified their needs and tested again. There was a real onus on library staff to manage quality control. It had to be a partnership process. We saw a danger that HLT staff might get in over their heads—but we were fairly confident that we already had a high level of IT competence right through the staff, a high level of understanding of what our current system did and did not do.

The essence of this method is that it needs to be written in a short sharp burst of activity. Expectations won’t change over a short-duration project. Projects that take a long time get caught in expectation creep—end users change their expectations as they see the project develop and long projects get caught in technology creep—the writers just get it nearly finished when something new and different comes along and they have to start again. We saw the initial process as taking something like ten weeks.

We finished up with something very tightly tuned to Horowhenua’s, and the librarians’ needs. But our finishing point would be but a beginning in the amazing world which is Open Source software.

Progress

Looking once again at our objectives:

Objective 1: A product that could be installed before the Y2K.

We did not work on Christmas Day 1999. We allowed ourselves one day off. But every other day, whether a so-called "holiday" or not, found us hard at it. And on January 5, 2000, the first day back, we had Koha installed and ready to go. The minimum (issues, returns, renewals and memberships) was achieved in the nick of time, truly, and by lunchtime we were starting to breathe easy; nothing like a go-live on incompletely tested software to test your mettle! Further development continued at a more decorous pace, and by June acquisitions and cataloguing were sufficiently bug-free for us to feel confident about announcing it to the New Zealand library world.

Objective 2: A product that is economical, in terms of initial purchase, license fees and maintenance support fees.

This objective had been achieved on all counts. The programming we commissioned cost us about 40% of the purchase price of an average turn-key solution. There was no requirement to purchase a maintenance contract, and no annual licence fees. When the commissioning stage was completed, we hired Katipo on an "as needed" basis, fixing bugs and developing minor enhancements.

We were able to use many of our older PCs, even including some diskless 486s, by running lots of copies of Netscape and Telnet on one of our servers, and using these old machines as dumb terminals. Only four 7-year old machines had to be discarded and replaced; all other purchases were enhancements to our network and services.

Objective 3: A product that runs effectively and fast by dial-up modem on an ordinary telephone line.

Katipo pulled out all the stops on this one. Each branch library had a little local network of one issues/returns machine and one OPAC, and they both worked just fine sharing one ordinary (not ISDN, not ADSL, just ordinary copper wire analogue) phone line, with an ordinary dial-up modem. The branches worked at very acceptable speed. At Levin, we experienced problems during very busy times at the circulation counter. After applying every fix we could think of we achieved some improvement, but the Telnet interface still let us down occasionally. Finally, the programmers went back to the beginning and rewrote the Telnet interface using a different interface library.

Objective 4: A product that uses up-to-the minute technologies, looks good and is easy for both staff and public to use.

Up to the minute technology was designed in. Looking good is subjective, but we liked it. It was easy to use; any patron with previous experience of the Internet had no problems using the OPACs at Horowhenua Libraries, and staff were happy that their part of the system was sensible and intuitive. But remember the Internet was still quite new, and in Horowhenua we have a predominantly senior population with many of them flummoxed by a mouse and by screens that assumed an understanding of "if it’s underlined and coloured, you can click it for more information". We held training sessions for anyone interested, and taught more people than we care to admit how to play solitaire, for mouse practice.

Objective 5: A product that permits members to access our catalogue and their own records from home as easily as in the library.

The OPAC was initially accessed only over the intranet, but Stage 2 followed within a few months and allowed patrons to access our database from home to check their loans, renew items and place reserves.

Objective 6: A product that lets us link easily to other sources of information – other databases and the Internet.

Internet access is available at all three libraries, and Stage 2 development saw links to other databases, including the Past Perfect database of the holdings of Horowhenua historical societies.

Community

Koha was a world first, the first open source library management programme. Although our initial development was not yet completed, we announced Koha in New Zealand in the July 2000 issue of Library Life. Word of mouth in the open source community is very strong, and approval was swift. It was only a matter of hours before we were noticed around the world. We received emails from New Zealand, then Australia, and Fiji, followed by North America and Europe.

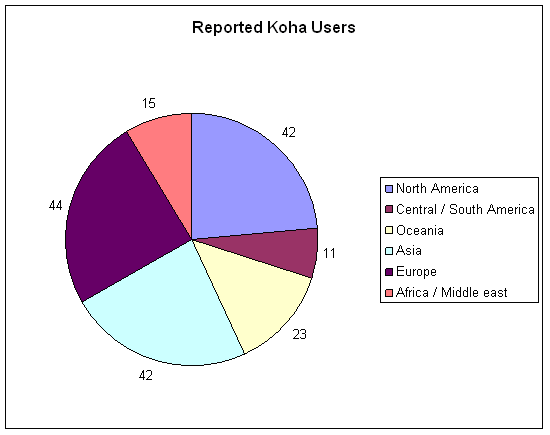

Figure 2: Koha Users as of 16 April 2009

An open source project is never finished. Someone will always see something else to improve and we were counting on this. We wanted to encourage a supportive community around Koha right from the start. Katipo set up web pages for inspection, a Listserv for discussion and the means for anyone interested to download the code. Within the first month, there were 368 downloads of Koha, the project webpage had 2,933 hits, and more than 50 people from around the world were on the mailing list. The first occasion when a technical question was asked, and it was answered by someone who was not working for Katipo or the HLT, was a real thrill. Very soon after the release of Koha 1.0 a newspaper library in New Zealand had the system fully installed for evaluation, libraries in Poland and Estonia had started to translate the front pages and students in America were suggesting additions that they might write as their contributions.

Since then Koha has gone on to win multiple awards including the 3M Award for Innovation in Libraries, the Interactive NZ Award in 2000, and the Trophées du Libre in 2003. Seven years after its release and a thriving project later, Chris Cormack won the Open Source Contributor award at the NZ Open Source Awards in 2007.

Open source projects only survive if a community builds up around the product to ensure its continual improvement. Koha is stronger than ever now, supported by active developers (programmers) and users (librarians) – and they actually talk to each other! A range of tools are employed to nurture the Koha community:

- Koha web site,

- Mailing lists: developers and general,

- Koha developers wiki,

- IRC real time chat,

- Koha documentation project,

- List of Koha libraries by geographical region,

- Koha extensions,

- Blog aggregator,

- Koha special interest groups (including Spanish, French, Italian),

- Conferences and workshops,

- Paid support vendors.

Support

There are a range of support options available for Koha, both free and paid, and this has contributed to the overall strength of the Koha project. Free support can be accessed from the website, and includes IRC, mailing lists, FAQs, and documentation. The site also lists vendors who provide paid support for those not confident enough with Linux to go it alone. These are drawn from around the globe, including not only New Zealand but also Australia, China, India, Pakistan, Africa, France, the UK and USA.

Support has never been limited to third party vendors. Steven Tonnenson worked on non-acquisitions based cataloguing, then moved on to write a web-based circulation module. His work formed the core of release 1.1.0 (January 2001). Pawel Skuza’s work on translations formed the core of release 1.1.1 and when 1.3.0 was released in September 2002 multiple flavours of MARC were also supported.

Many of the existing submitters have been involved since the beginning: BibLibre’s Paul Poulain and Henri-Damien Laurent; Stephen Hedges, Owen Leonard and Joshua Ferraro (Nelsonville Public Library); and MJ Ray from Turo Technology. They all joined the community in 2002.

Vendors like Anant, Biblibre, ByWater, Calyx, Catalyst, inLibro, IndServe, Katipo, KohaAloha, LibLime, LibSoul, NCHC, OSSLabs, PakLAG, PTFS, Sabinet, Strategic Data, Tamil and Turo Technology take the code and sell support around the product, develop add-ons and enhancements for their clients and then contribute these back to the project under the terms of the GPL license.

Assessment and Learning

Looking back from a distance of 10 years, there are a few things we should have done differently:

Participation

Firstly, we did not participate in the community. Once we had our own Koha up and running, and had made the code available for download, we basically abandoned it. We relied on Katipo to represent us in the Koha community when we should have taken responsibility for this ourselves. I guess we had scratched our own itch and simply moved on, but there was also an element of a medium-sized public library in New Zealand developing something simple and then going head to head with big American libraries who needed it to be more.

What we should have done was stayed active and joined in discussions, articulating and defending our approach and vision. Koha was designed in what is now described as a FRBR [5] arrangement, although of course it wasn’t called that 10 years ago, it was just a logical way for us to arrange the catalogue. A single bibliographic record essentially described the intellectual content, then a bunch of group records were attached, each one representing a specific imprint or publication. Attached to the group records were any number of items or individual copies, and items inherited all the attributes of the group they were attached to, and groups inherited all the attributes of the bibliographic record they were attached to. This made it very easy to reserve the first item which became available; really good when you didn’t care if you got the Collins 1999 copy of ‘A Title’ with 100 pages or the Random 2007 paperback edition of ‘A Title’ with 124 pages. We should have had the courage of our convictions and also the confidence to defend the decisions we made. To this day I don’t think anyone understands that structure, although remnants of it remain in the current 3.0 release. The current RDA [6] work is quite exciting for us and it feels like we will be coming full circle in due course.

Stay with the Main Trunk

We also made the mistake of not carrying out regular upgrades in order to stay in the main development trunk. We had such a perfectly working, highly customized and very stable library management system that we really didn’t see any need to upgrade to something which we didn’t need. For example, Koha was developed to handle multiple flavours of MARC quite early in its development, something we had completely ignored when designing the system. We could see no obvious benefit to be gained from cataloguing in MARC, preferring to continue cataloguing by filling out fields on a form. Implementing MARC into Koha ensured the widespread appeal of the programme but it did make our FRBR system work very awkwardly.

Basically Koha forked and we remained on a rock solid but isolated branch with a system we had to maintain ourselves, which meant that every single upgrade forever into the future would require extensive customisation. This effectively meant we did not receive any of the financial gains of OSS software development. We held out for 5 years before finally upgrading from v 1.x to v 2.2.4 in 2005. This was a massive upheaval and key modules which had worked perfectly for us for 5 years were irrevocably broken in our eyes; periodicals, simple acquisitions and catalogue maintenance were the ones we mourned for the longest! Koha was essentially a whole new programme by this point, and we had absolutely no one to blame but ourselves.

We are philosophical about it now; it’s the nature of open source. To control or shape development you have to participate: either contribute code yourself or fund development, but definitely join in the discussion. OSS development is much more consensual than you would think. Ideas and issues are tossed around until a clear path forward is agreed upon and decisions tend to be stronger for it.

Applying the Learning: Koha 3.0

The release of Koha 3.0 in late 2008 brought Koha completely into the web 2.0 age and all that entails. We are reconciled to taking a small step back for now, but the FRBR logic is around and RDA should see us back where want to be in a year or so – but with all the very exciting features and opportunities that Koha 3 has now.

This time we are determined to take control of our own system and not operate in isolation. While we weren’t quite up to downloading the code and getting it all working, we have taken responsibility for working through all the system preferences and settings, and working out the best arrangement of the collection within the database. There are so many ways to make Koha work, not just one right way, and while this is a great thing it has taken a bit to get used to.

We have invested many hours in trying to understand the new terminology, like what "Item Types" mean in Koha 3.0 as opposed to "Collection Codes". It is different from how we used them in 1.0 and in 2.0 also. It’s definitely better but it has taken us time to understand the logic behind changes made from 1.0 to 2.0 then on to 3.0. We are getting involved again, benefiting from the generosity of the community in sharing learning and experience. Every time we have asked for help, help has been at hand. In return we have made a conscious decision to participate fully on the lists, sharing the knowledge we have gained.

In the early days, the Koha list appeared to have been dominated by programmers but I have noticed a lot more librarians participating now. This is great as we do understand Koha from a different perspective, but we need to continue to develop Koha together.

Conclusion

The declining global economic situation means libraries must review how they invest their operating budgets to maximise return to the communities they serve. To quote the recently published Darien Statements [7], we need to: "Adopt technology that keeps data open and free, abandon[ing] technology that does not." The time is right for OSS. It fits the library philosophy of sharing and accessibility and cooperation.

Developing and releasing in open source has worked well for Horowhenua Library Trust. We started the ball rolling with a local solution but like a snowball it gained its real power through the momentum gained of a global community of brains and expertise. Our name for our project may have been a premonition, but we’re proud to have offered our koha to the library world.

E iti noa ana na te aroha

Small gift, given in love

(Mäori proverb)

References

[1] The Trustees of Horowhenua Library Trust in 2000 were: Alan Hercus (Chair), George Sue, Heather Birrell, Louise Robbie and Peter Hodge.

[2] Rosalie Blake, Towards Superior Service : a Review of the Operations of the Horowhenua Library Trust (June 1998). Available at: http://kete.library.org.nz/site/topics/show/16-towards-superior-service

[3] http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/gpl.html

[4] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_and_open_source_software

[5] FRBR : Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records. A conceptual entity-relationship model developed by IFLA that represents a more holistic approach to retrieval and access as the relationships between the entities provide links to navigate through the hierarchy of relationships. The model is significant because it is separate from specific cataloguing standards such as AACR2 or ISBD. For more information: http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/whatfrbr.html

[6] RDA: Resource description Architecture is the new cataloguing standard being developed to replace AACR2 rev. in 2009. It goes beyond earlier cataloguing codes in that it provides guidelines on cataloguing digital resources and a stronger emphasis on helping users find, identify, select, and obtain the information they want. RDA also supports clustering of bibliographic records to show relationships between works and their creators. This important new feature makes users more aware of a work’s different editions, translations, or physical formats. Underlying RDA are the conceptual models FRBR (Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records) and FRAD (Functional Requirements for Authority Data). For more information: http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/jsc/rdaprospectus.html

[7] The Darien Statements were written by John Blyberg, Kathryn Greenhill and Cindi Trainor in the days following the "In the Foothills: a Not-Quite Summit on the Future of Libraries" at which participants were instructed to "come prepared to help sketch out the role librarians should play in defining the future of libraries". This was held in Darien, USA, 2009. More information: http://www.blyberg.net/2009/04/03/the-darien-statements-on-the-library-and-librarians/

About the Authors

Joann Ransom is currently Deputy Head of Libraries at Horowhenua Library Trust, Levin, New Zealand. She has worked on two award winning open source projects: as one of the team who developed Koha back in 1999-2000, and more recently leading development of Kete, an open source project for building a community digital archive of articles, images, audio, video and documents. Joann is a professional librarian with qualifications in English literature and computer network administration. She regularly blogs and tweets jransom, and leads a quiet life in a small coastal village with her menagerie of children and pets.

Christopher Cormack has a BSc Computer Science and a BA Mathematics and Maori Studies. While working for Katipo Communications he was the lead developer of the original version of Koha, which went live at Horowhenua Library Trust January 5, 2000. Since then he has served various roles in the community, release manager, QA manager and currently Translation manager. Christopher believes in Free Software, and allowing users the freedom to innovate.

Rosalie Blake has worked at Horowhenua Libraries since 1981, in a variety of positions which she keeps reinventing. Currently Head of Libraries for the Horowhenua Library Trust, which came into being in January 1997. Loves computers, email, web pages . . . so it’s not surprising she was willing to take a punt with Koha, the world’s first open source library system. She has served several terms as Regional and National Councillor for LIANZA, being responsible for the Great New Zealand TV Turn-Off (a Library Week promotion), and the 1995 edition of the Public Library Standards for New Zealand Libraries. She has an absurdly large garden which she shares with a cat and a dog.

Joann Ransom, 2009-06-26

Correct link for Towards Superior Service report: http://kete.library.org.nz/site/topics/show/16-towards-superior-service

João, 2009-07-04

A good history about Koha ILS and open source for libraries. Thanks.

Verónica Lencinas, 2009-08-06

“FRBR arrangement”: it was one of the first things I liked when I saw the database structure of one of the first releases. I thought: wow, they implemented FRBR! But there was no Marc support and that was very bad for our team.

(Very happy Koha 2.2.9 and Koha 3 user from Argentina)

Topic 6 Task » OUA IMT Study Area, 2012-08-23

[…] Ransom, J., Cormack, C., & Blake, R. (2009). How Hard Can It Be? : Developing in Open Source. Code4Lib Journal, (7). Retrieved from http://journal.code4lib.org/articles/1638 […]

Topic 6 Task » TIS Assessment One, 2015-02-12

[…] Ransom, J., Cormack, C., & Blake, R. (2009). How Hard Can It Be? : Developing in Open Source. Code4Lib Journal, (7). Retrieved from http://journal.code4lib.org/articles/1638 […]

Topic 6 Task » Information Services Foundation Practicum, 2015-09-03

[…] Ransom, J., Cormack, C., & Blake, R. (2009). How Hard Can It Be? : Developing in Open Source. Code4Lib Journal, (7). Retrieved from http://journal.code4lib.org/articles/1638 […]

Topic 6 Task – blog recycle test, 2015-12-30

[…] Ransom, J., Cormack, C., & Blake, R. (2009). How Hard Can It Be? : Developing in Open Source. Code4Lib Journal, (7). Retrieved from http://journal.code4lib.org/articles/1638 […]