By Kelly Stewart & Stefana Breitwieser

Introduction

As archives increasingly have acquired born-digital material, traditional methods of collection access need to expand to include digital files. However, technical challenges can potentially frustrate archives’ best efforts at leveraging meaningful metadata for searching, as well as serving, these files to researchers. In response to these challenges, the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) is launching SCOPE, a browser-based access interface for digital material. SCOPE has been developed in partnership with Artefactual Systems, a company based in New Westminster, Canada, and the lead contributor to two other open-source applications: Archivematica and AtoM. As a free and open-source tool, we hope to offer the digital preservation community not only a potential solution for digital collections access, but also a case study for collaborative technical solutions.

Why SCOPE? SCOPE-ing out parameters for born-digital access

The CCA is an international research institution and museum focused on the study and practice of architecture; it produces exhibitions and publications informed by its extensive archives, library, photographs, and prints and drawings collections. Beginning in 2012, the CCA began investigating a new research question: “How did the introduction of digital technology affect architecture and architectural practice?” What followed was the Archaeology of the Digital project, culminating in two books, three museum exhibitions, and more than twenty-five e-publications. The acquisition of twenty-five archives with a significant digital component as a part of this project led to a different kind of research question for the CCA archives staff: “How do we process, preserve, and make accessible more than 5TB of complex born-digital archival material?”

Preservation of these born-digital files was our starting point. The digital archives staff of five began to work through the five terabytes of born-digital archival material dating from 1988-2012, comprised of roughly one million files. The goal was not only to preserve and make accessible the material from these archives, but to also layout a blueprint for what an Open Archival Information System (OAIS) compliant preservation system might look like at the CCA. OAIS is the ISO-standard for digital preservation, which requires institutions to accept materials from information producers, have control over the materials in such a way that ensures long-term preservation in a self-described or independently understandable way, follow approved policies and procedures, and finally make the materials available to the designated community of intended users (Lavoie, 2014; Schumann and Recker, 2012). OAIS also defines different types of information packages that can be maintained over time: submission information packages (SIPs), or the material as it was transferred from the donor and prior to ingest in a digital preservation system; archival information packages (AIPs), or the preservation copy; and dissemination information packages (DIPs), or the access copy (Lavoie, 2014).

Processing of the twenty-five Archaeology of the Digital archives followed the usual digital archival workflows: original digital storage media was disk-imaged using a BitCurator workstation. Files were carved from the disk images, and then were arranged and described. Tim Walsh, CCA’s former digital archivist, also developed a suite of open-source tools used for digital archival processing, including Brunnhilde to characterize groups of files and to flag potential preservation issues, and CCA Tools to package SIPs in a uniform way and automate description. Potential preservation issues and other archival processing considerations, like corrupted timestamps or duplicate files, were corrected or accounted for as much as possible through manual clean-up and minor bash scripting. Automated description was then supplemented by the digital processing archivists, following the General International Standard Archival Description (ISAD-G) and local standards. The metadata was then entered into CCA’s database of record, The Museum System (TMS).

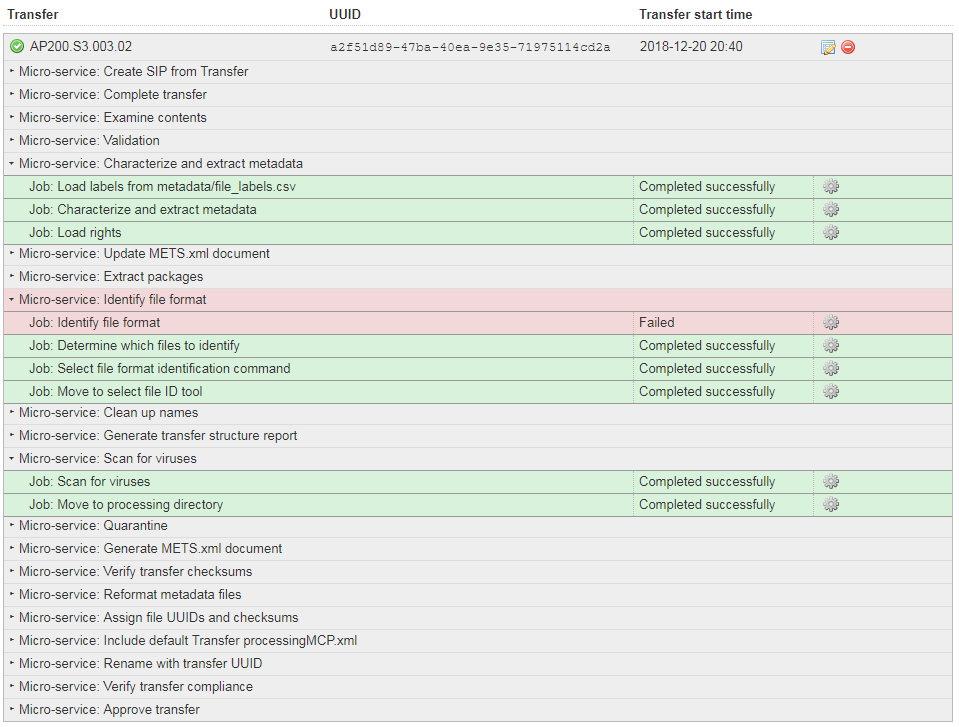

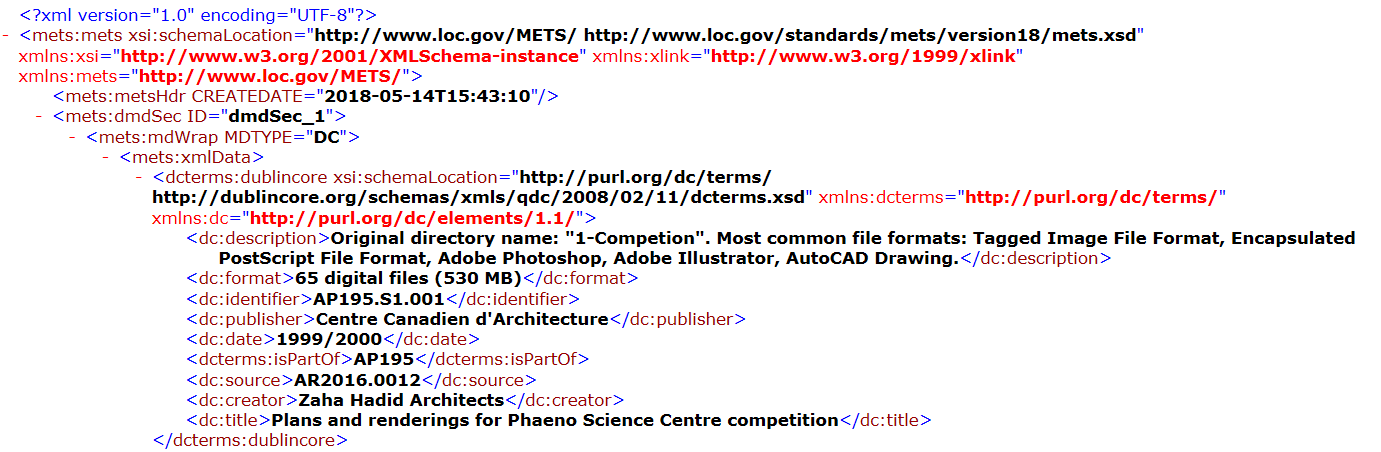

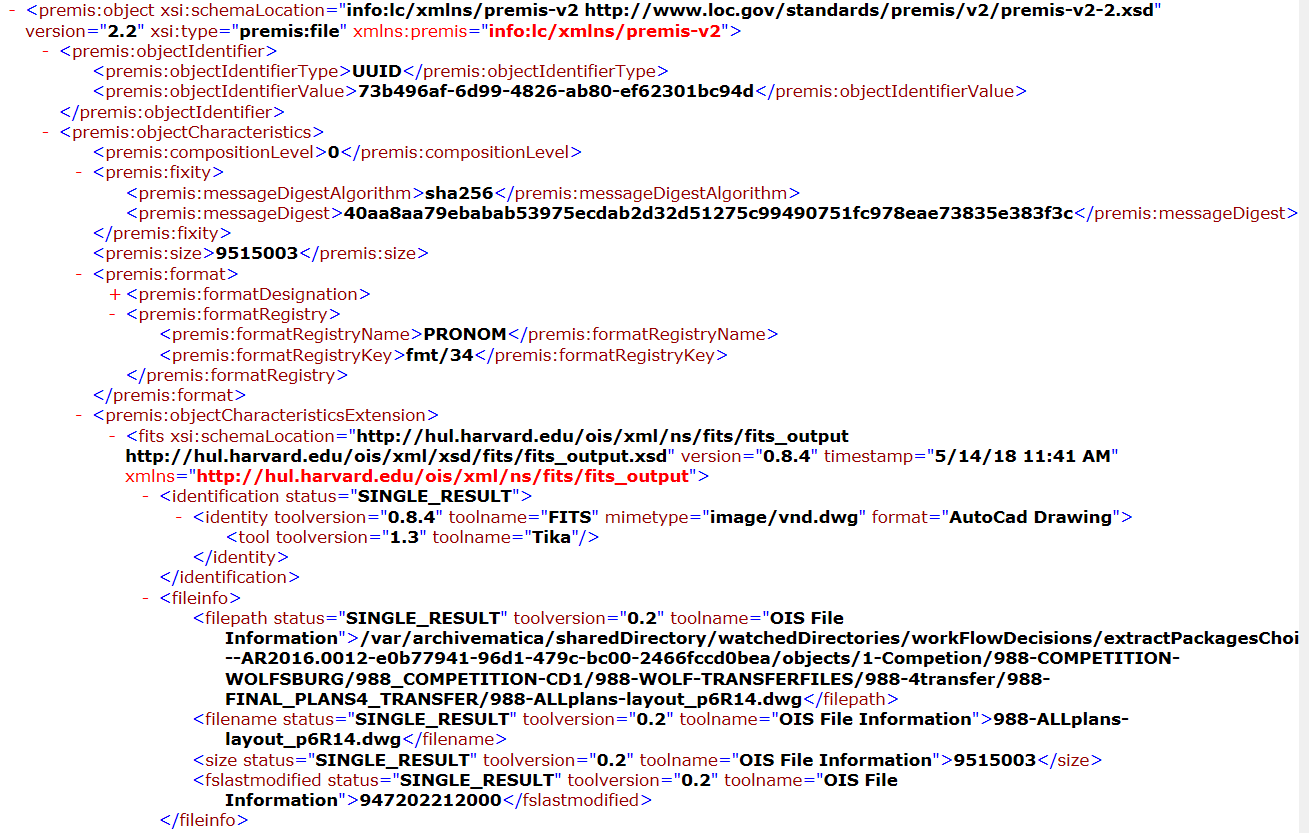

Following processing, the material was ingested into Archivematica, the digital preservation system built by Artefactual. Archivematica enacts a number of preservation micro-services (including identifying files and generating related metadata), describes each of these micro-services as a PREMIS event, and packages this information into a METS file stored with the AIP. Archivematica does fixity checking on stored AIPs to ensure the files remain the same over time, and generates DIPs for user access.

Figure 1. Screenshot of micro-services performed by Archivematica on a particular SIP. PREMIS metadata is generated for each of these services, and put into a METS file.

However, even though the CCA’s AIPs were well-preserved and granularly described, we found that providing meaningful researcher access to the files and their descriptions was difficult. We were confronted with two problems.

First, the existing workflow for serving the files to researchers was becoming unsustainable in that it was time-consuming, labor-intensive, and required input from many stakeholders. That workflow was as follows: A researcher made a request for the digital material and reference staff forwarded the request to the digital archives team. An archivist queried the Archivematica AIP storage server to generate a DIP on the local machine, moved the DIP to a shared folder with the researcher, and finally unzipped the files. The archivist then notified the researcher and reference, which often resulted in a consultation on how to use the files. In instances where dozens of DIPs were requested, this workflow could take hours.

Though born-digital archival material has only seen modest use as a percentage of CCA’s total researchers, use has still more than doubled in the two years we have made the material available with four external researchers in 2017 and ten in 2018. Internally, CCA’s interest in digital architectural materials has remained strong across its programming and publishing and as an institution has committed itself to increasing visibility and expanding scholarship around these materials. We saw this moment as an opportunity to improve access workflows for these materials in order to better accommodate research as it reaches its expected critical mass in the coming years.

Our second problem was that traditional archival research methods seem to apply less to digital materials. Historically, archival research has been conducted in the top-down method dictated by finding aids, starting at the collection-level description and moving downwards until the appropriate material is found. This method works well for traditional qualitative research questions: “What drawings do you have for Zaha Hadid’s Phaeno Science Center?” However, the digital humanities occasionally have shifted archival research to a more quantitative focus: “I’m trying to discover how 3D modeling software has evolved over time. Can I look at every Rhinoceros file made in 2002 from across all collections?” Being able to answer these types of questions would require both a deep individual knowledge of our digital holdings and endless time pouring through finding aids, an increasingly unscalable expectation due to the growing volume of available digital material. Aggregate description typically used in finding aids also provided a significant barrier to answering these extremely specific questions.

Looking at these two problems, we knew that we had to both streamline our workflow as well as take advantage of the granular file-level description created by Archivematica. After assessing existing solutions, however, we felt that building a custom application was the only way forward. AtoM, the archival management system also developed and maintained by Artefactual, was considered but ultimately decided against given that the CCA’s description is currently in TMS and it seemed unwise to manage description and files across two archival management systems. Other digital repository systems, like DSpace and Islandora, were too heavy and often displayed information in a way that did not necessarily reflect archival hierarchies in a meaningful way. Their interfaces were also often in English only, falling short of Quebec legal requirements. We also considered adapting the existing CCA website; however the millions of item-level descriptions for digital files would have appeared alongside library books and fonds-level description, creating a lot of unnecessary noise and cluttering search results.

Figure 2. Sample Dublin Core metadata, written by a processing archivist, as it appears in the Archivematica-generated METS file.

Figure 3. Sample PREMIS metadata, created by Archivematica to document micro-services, as it appears in the Archivematica-generated METS file.

With all this in mind, Tim Walsh designed and built a proof-of-concept for SCOPE in 2017, which has now evolved into a fully-functional browser-based access interface for DIPs developed by Artefactual.

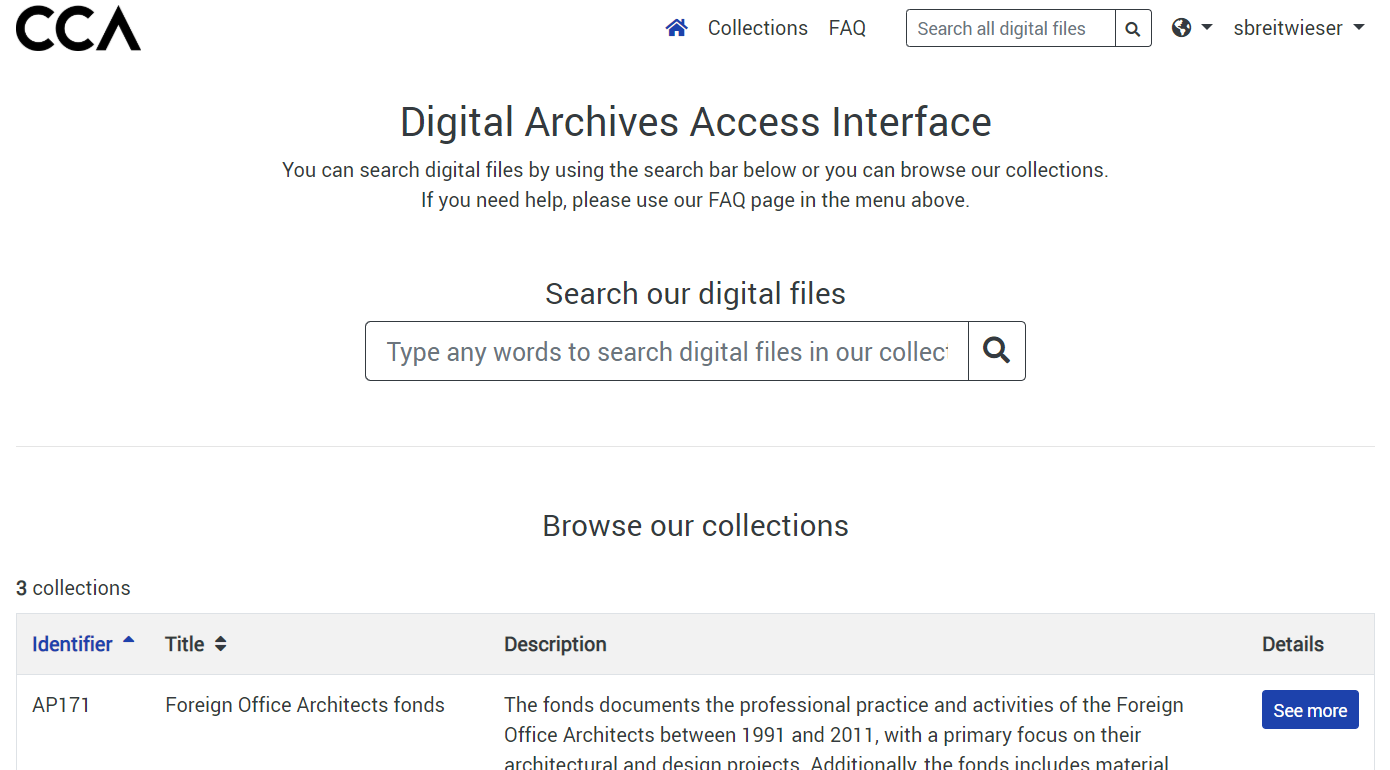

SCOPE allows archives staff to upload DIPs to the interface, which then uses the METS file in the DIP to display folder- and file-level metadata. Researchers receive a login, search this metadata to find individual files or entire DIPs, and download the DIPs directly to the locked-down workstations in the CCA study room via a link on the interface. Researcher access to SCOPE is only available on these workstations, where internet and USB access is blocked. Material cannot be moved off of the workstations or accessed elsewhere. (Note that DIPs can only be downloaded as a whole, not as individual files. This is for several reasons, particularly to maintain archival context and to not break files with external references, common with architectural formats.)

Figure 4. Screenshot of the SCOPE home page.

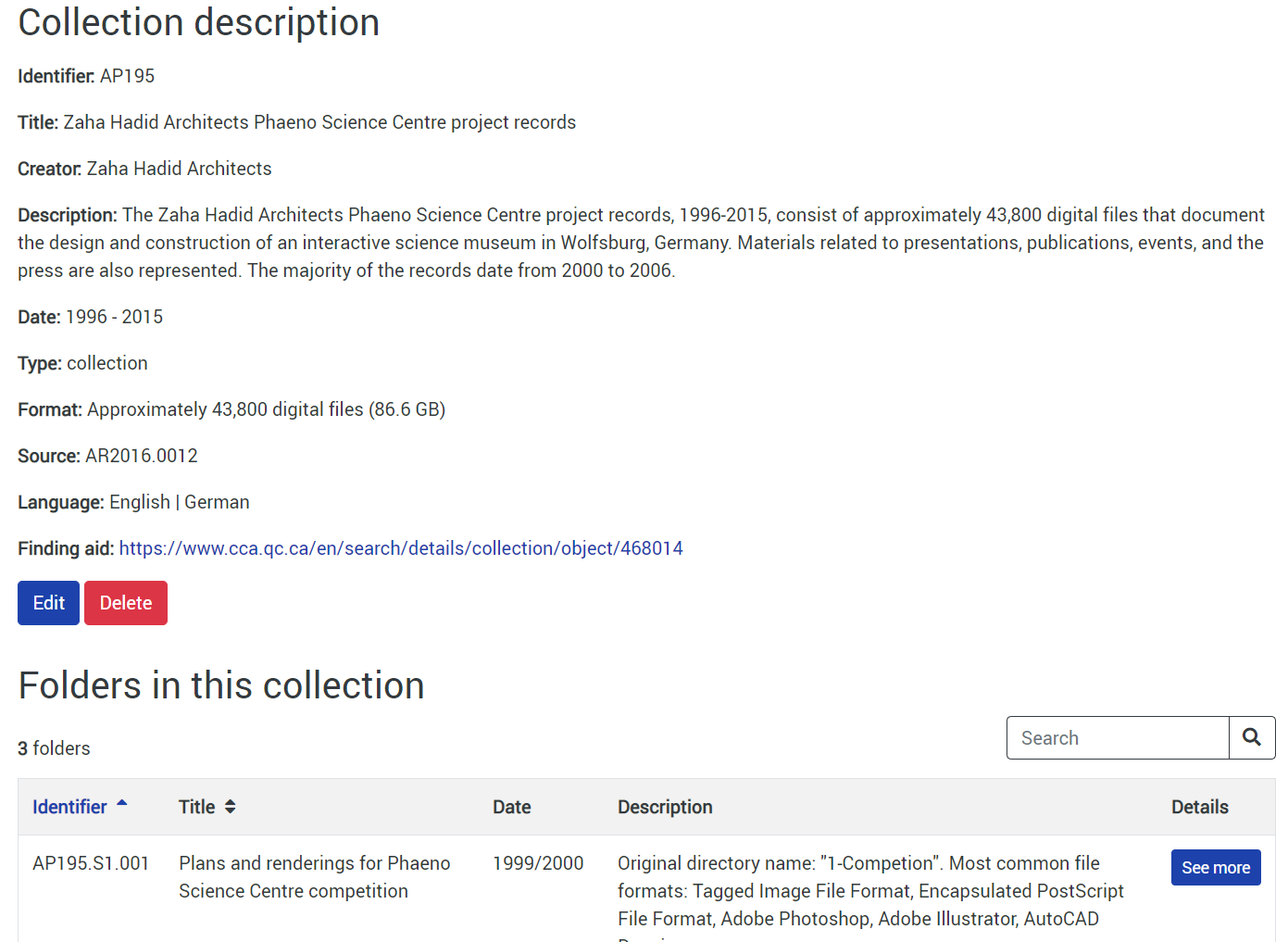

Figure 5. Screenshot of a Collection-level page in SCOPE.

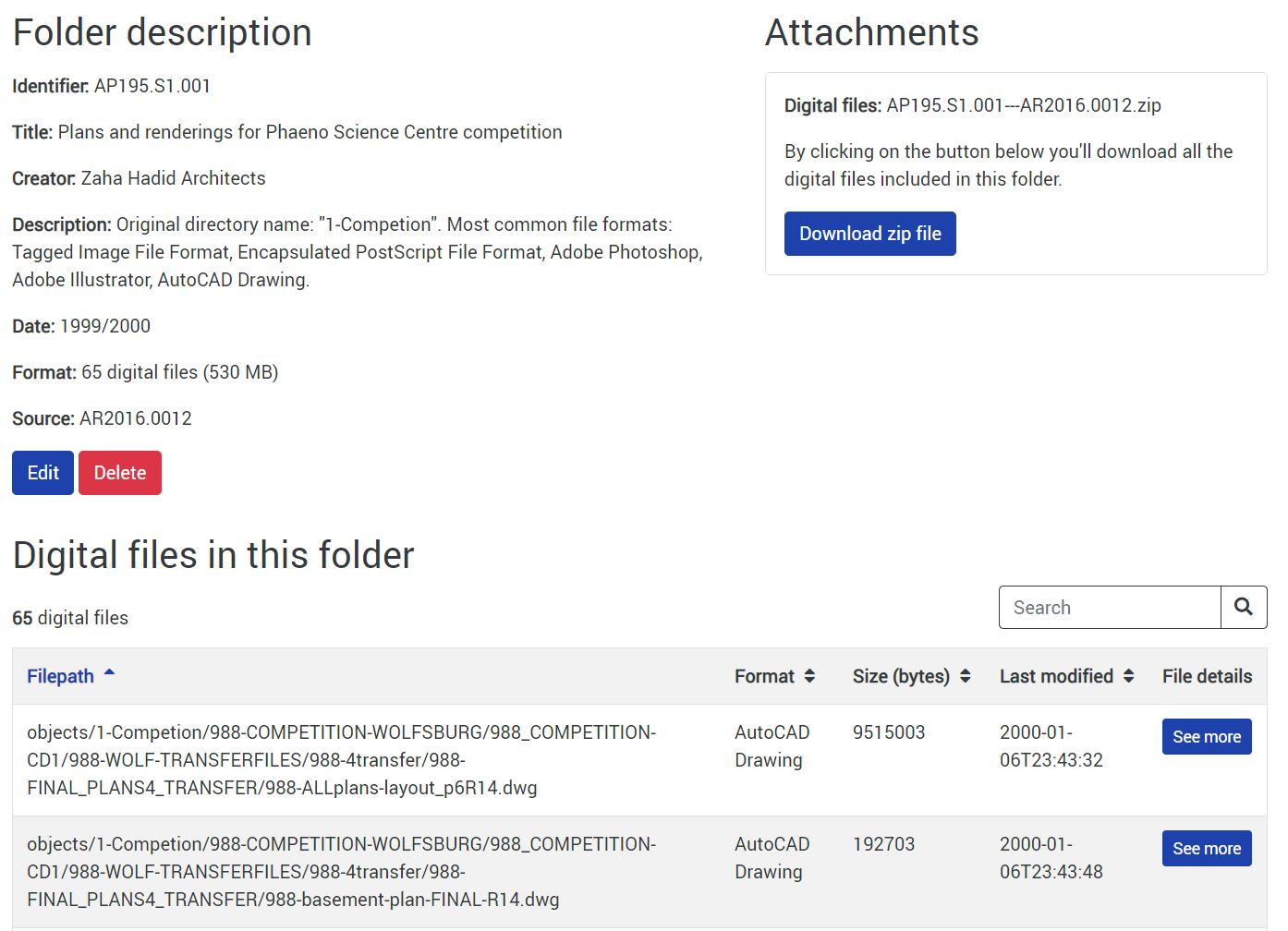

Figure 6. Screenshot of a Folder-level page in SCOPE. Note the “Download zip file” button.

Reference staff and archivists no longer need to mediate the request, meaning the turnaround time is significantly faster. Searching is also greatly improved. The file-level metadata in the METs file is now discoverable, and searches can be conducted across all collections at once. Researchers have direct access to file-level metadata, including file name, file format, last modified date, and size, which we were not able to display previously given the format of our finding aids. It also allows for display of PREMIS events, which makes archival processing more transparent to our researchers.

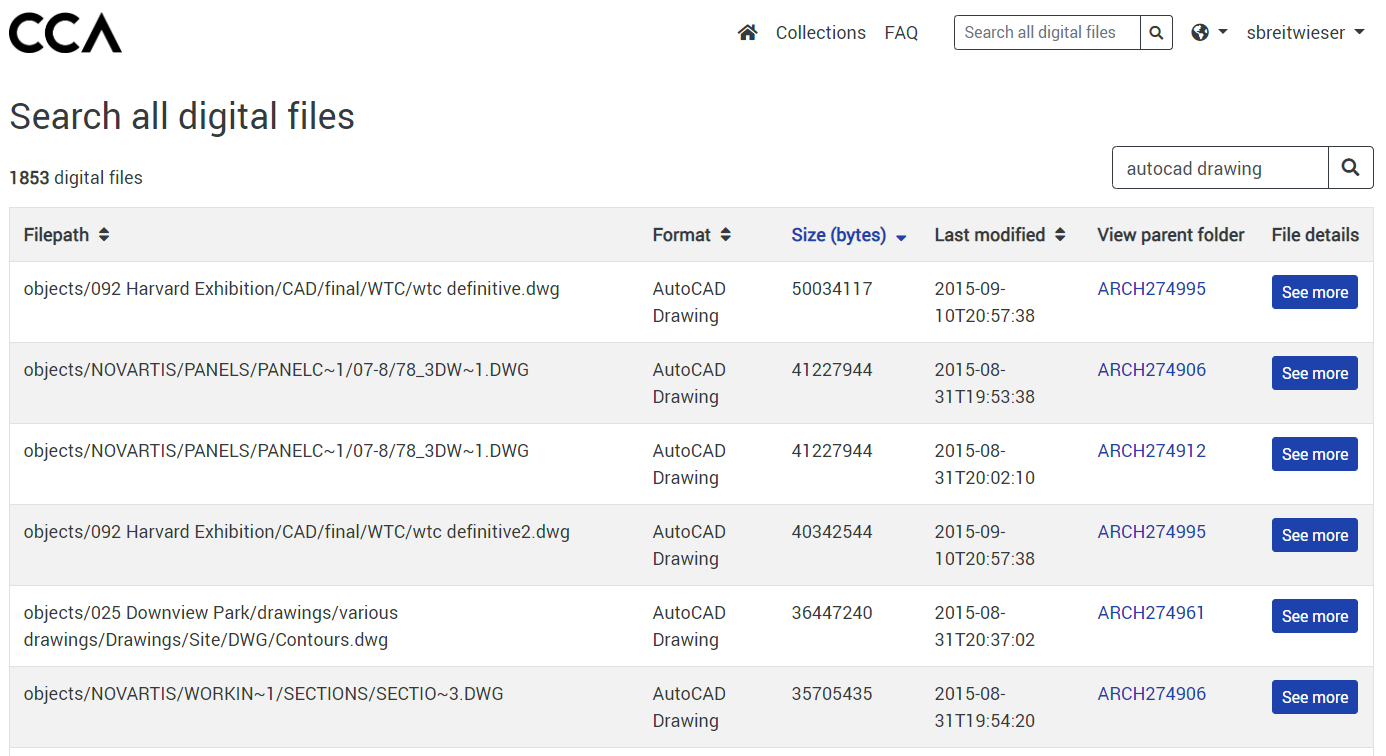

Figure 7. Screenshot of the search results for “AutoCAD drawing” in SCOPE.

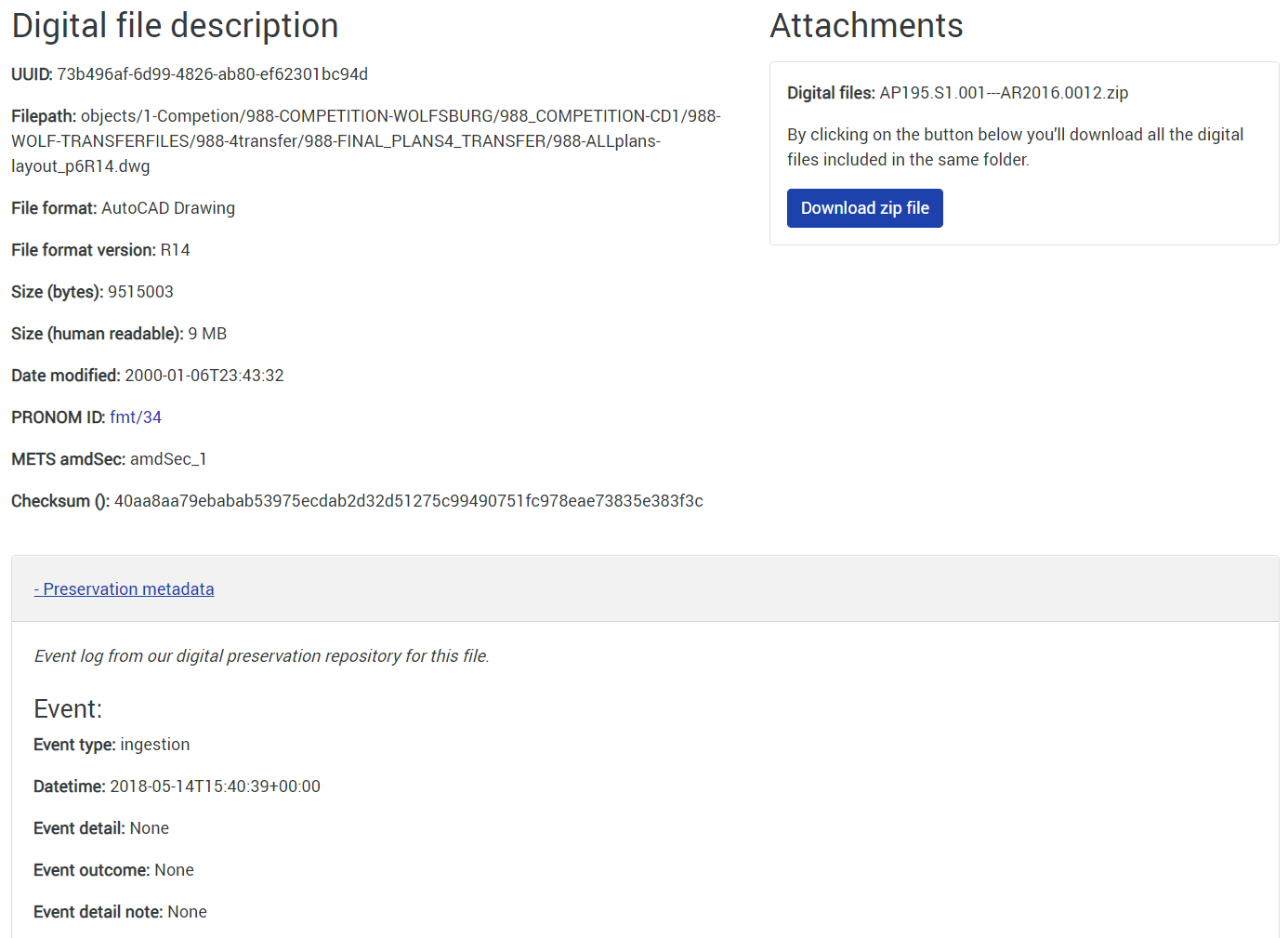

Figure 8. Screenshot of Item-level page in SCOPE, including documentation of the PREMIS events (titled “Preservation metadata”).

A Team Effort

Collaborating with Artefactual was an easy, but necessary decision. The first reason for doing so was a practical one. Though our archives staff has a reasonably high level of technical skill, building a full-fledged application would require the work of professional developers. Secondly, because an important eventual feature of SCOPE is integration with our Archivematica storage, Artefactual felt like a natural collaborator due to their expertise with their product and their understanding of archival practices and principles. The CCA ended up sponsoring roughly 700 hours of Artefactual’s developer and analyst time over two phases from Summer 2018 to Spring 2019.

Collaboration is embedded in Artefactual’s work culture. Typically, a development project includes an archivist/librarian (analyst), a software developer, and a project manager. The analyst is the subject specialist who has both who has the training and expertise in the field and can translate the client’s feature request to the software developer through various means, including wireframes and feature files. Finally, the process is overseen by a project manager, who takes care of administrative tasks and makes sure that everyone across both organizations is moving towards a successful conclusion.

It was also a collaborative effort across the CCA. Archivists and other collections staff worked to communicate their needs for this application, and with the help of Artefactual, translated these into particular features for the developer. Members of CCA’s Digital Division also contributed valuable expertise in digital project management and user experience testing.

Two user experience sessions with CCA staff during the first phase were able to inform development moving forward. These sessions made it clear that any final product needed to be not just functional, but also intuitive and easy to use. They also gave us the opportunity to help conceptualize certain functionalities, particularly filtering and faceting search results, with real users.

In practical terms, collaboration across the two organizations centered on producing a beta version of an application that would enable researchers to access meaningful content in Archivematica DIPs from within the CCA’s study room. The CCA provided user stories and wireframes that informed the initial conceptual stages of the project. Artefactual then wrote feature files in the gherkin syntax (the translation document between user and developer) to more fully describe the CCA’s desired functionality. From there, development proceeded as outlined below. Ultimately, the beta version of SCOPE was demonstrated at the CCA with feedback from those sessions folded into discussions for a potential second round of development.

Development followed an iterative, Agile process, with calls between the CCA and Artefactual taking place every other week. These calls provided an opportunity for the CCA and Artefactual to review progress since the last discussion, address questions, and review/modify upcoming priorities. The code is housed in GitHub in the CCA organization as a repository called dip-access-interface. Artefactual staff were given access to GitHub.

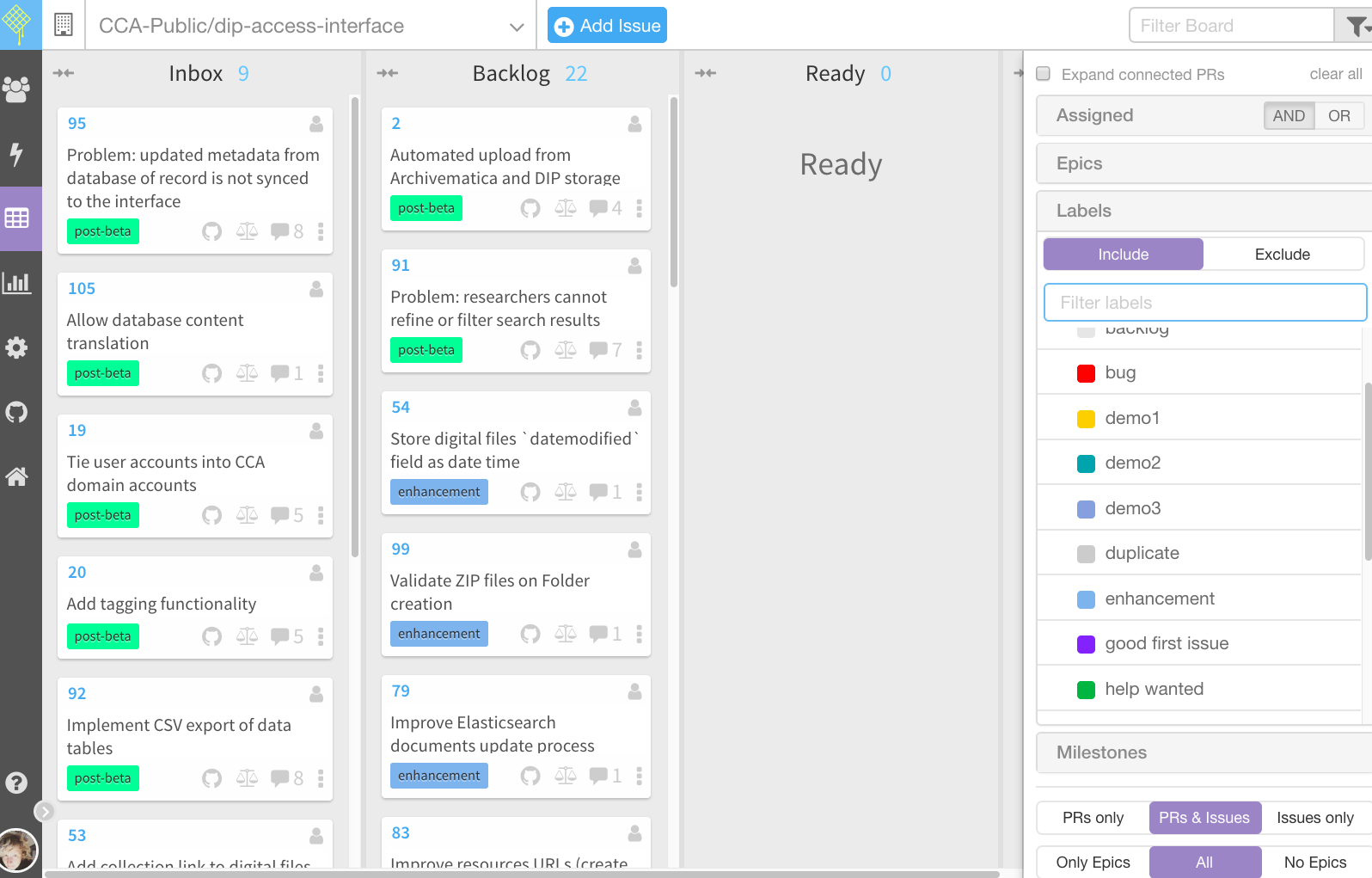

In order to manage the project overall, we used Waffle, the same tool that Artefactual uses to manage Archivematica. From Waffle, the entire team could look at issues with their associated pull requests and track progress as they were created, edited, reviewed, tested and completed. Both GitHub and Waffle enable labels, and Waffle allows filtering by label so that the user can select the label ‘help wanted’ and then view all issues and pull requests with that label. For example, for this project, ‘demo1’, ‘demo2’, and ‘demo3’ labels were created and associated with issues that needed to be complete in order to successfully run the first, second, and third demonstrations that CCA ran internally to its user groups. SCOPE’s Waffle board was used extensively to organize work in progress, work ready for review, and upcoming tasks throughout all phases of the project. This approach allowed for on-the-fly re-scoping and re-prioritizing, which resulted in a product that more closely addressed the overall intended outcomes.

Figure 9. The SCOPE waffle board, ready to go for Phase 2 of development.

Future Work

We are now looking at a second round of development that will take SCOPE to ‘post-beta’. The first round was meant to deliver a useable product. The second will introduce new features and revise existing features.

The most major update will be SCOPE’s integration with Archivematica’s DIP storage. We are analyzing Archivematica’s current DIP creation workflow and comparing it to the CCA’s use of Automation Tools (AT) to generate DIPs to determine the best way forward (Issue #117). It is possible that we will continue to use AT to generate the type of specialized DIP that the CCA requires. However, it’s also possible that we integrate the DIP upload functionality to SCOPE within Archivematica itself. Time will tell as we work through this second phase!

The other major update will involve improved searching (including faceting and filtering). Currently, researchers cannot search by date range or by file format, nor can they refine search lists or use tags (Issue #91). This will represent another step forward as we take advantage of granular item-level metadata created by Archivematica.

Additional features will also include reporting for reference and collection statistics, using Google Analytics and Kibana respectively, to be able to better understand how collections are being used, what the digital archive consists of, and how it is growing over time.

We will also be addressing the nearly thirty outstanding GitHub tickets related to back-end updates and user experience.

Conclusion

Like any product, a software application needs to be maintained in order to stay relevant. There are dependencies within the application and external environmental or organizational factors that need attention. The great power of open source software is that ideally it’s the community which, through various means, contributes to the ongoing maintenance and continued relevance of the application. There is no vendor lock-in, but the trade-off is that those vested in the product must also accept responsibility for its ongoing care. It’s been said that an open source software application is like having a kitten. When someone is given a free kitten they don’t have to pay for the animal but there are vet bills to pay, food to prepare, and love to give to make sure the cute little kitten grows up to be a well-fed and contented cat.

SCOPE is that cute little kitten right now, or maybe, since we’re not out of beta, it’s still in utero. In order to make sure it grows into a DIP lovin’ cat, SCOPE needs to be housed, to be used, to be documented. Those who are interested can download the application and try it out in conjunction with Archivematica. When they do, they can contribute back to the project through many avenues: troubleshooting on a user forum, doing code review, writing code, and identifying or commenting on issues. In doing so, they are implicitly agreeing to become part of SCOPE’s community of care which will ensure the continued longevity of the application. If you are interested in learning more about SCOPE please contact the authors. You can also check out our Waffle board or our github repository. We look forward to hearing from you!

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tim Walsh (Digital Preservation Librarian, Concordia University Libraries), Bun Ek (Digital Projects Manager, CCA), Marc Boucher (Information Technology, CCA), Martien deVletter (Associate Director, Collection, CCA), and Sophie Couture (Associate Director, Digital, CCA) for their work on SCOPE.

Additional thanks to Digital Processing Archivists Justine Couture, Alexandra Jokinen, and Mireille Nappert, as well as Digital Archives Technicians Kyle Dennis and Anne-Marie Trépanier, for their work processing the Archaeology of the Digital collections.

SCOPE is generously funded by the Montreal Cultural Development grant awarded by the City of Montreal and the Quebec Department of Culture and Communications.

About the Authors

Kelly Stewart (kstewart@artefactual.com) is Director of Archival and Digital Preservation Services for Artefactual Systems. She holds a Master of Archival Studies degree from the University of British Columbia and has many years experience as a consultant and educator in archives and records management, specializing in policy work, business process analysis, facilitation and teaching. She has worked for Artefactual since 2017.

Stefana Breitwieser is the Digital Archivist at the Canadian Centre for Architecture. She can be reached at sbreitwieser@cca.qc.ca with any questions related to SCOPE or born-digital archives.

Bibliography and Notes

Lavoie, Brian. The Open Archival Information System (OAIS) Reference Model: Introductory Guide (2nd Edition). Digital Preservation Coalition; 2014 [cited 2019 January 10]. Available from: https://www.dpconline.org/docs/technology-watch-reports/1359-dpctw14-02/file

Schumann, Natascha and Astrid Recker. Demystifying OAIS compliance: Benefits and challenges of mapping the OAIS data model to the GESIS Data Archive [Internet]. IASSIST Quarterly; Summer 2012 [cited 2019 January 10]. Available from: https://iassistdata.org/sites/default/files/iqvol36_2_recker.pdf

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply