By Avgoustinos Avgousti, Georgios Papaioannou, and Feliz Ribeiro Gouveia

Introduction

This paper addresses a fundamental gap and challenges incontent disseminationin Cultural Heritage institutions. With the advent of the internet, the digital age has influenced almost every aspect of human activity and has transformed it in a revolutionary way never seen before. In particular, the domain of Digital Cultural Heritage has gained in popularity during the last decade. The scientific community has shown new possibilities for integrated access to Museum and Archival collections. Cultural heritage organizations are increasingly eager to cooperate and provide the best possible access to their collections through the Web.

Access to Cultural Heritage assets provides users with a wide range of opportunities to gain new knowledge. Memory institutions (Stainforth, 2016) were probably the first to digitize information, creating online databases to which access was granted only locally through on-site servers. Since then, the internet has allowed people to access knowledge from their home computers and increased the number of users drastically. Nowadays the digitization process is essential in the Cultural Heritage domain, and its accessibility is improved continuously due to open-source communities and technological advancements (Cimadomo et al., 2013). However, Museum and Archival collections known outside of the area of their discipline are usually supported by large consortiums, expensive technology, and generous funding awards, e.g. Europeana[1], The Metropolitan Museum of Art Collections[2], The British Museum[3] and so forth. (Meghini et al., 2017) and (Dombrowski, 2016).

Problem Statement

Unfortunately, the potential of new methodologies and tools to have a transformative impact on individual research and smaller projects is higher than the grant funding available to support extensive, expensive, and extravagant technical undertakings. Although there are plenty of ideas for creating online museum collections, there are also many limitations. Currently the majority of small museums willing to follow large cultural heritage institutions digitization steps are usually not able to obtain expensive technology. Furthermore museums do not usually hire experts to plan, develop, deploy and maintain a digital collection for them, but delegate them to museum humanities scholars who are often limited in their technological skills. The recruitment of experts with experience and skills is costly, leading to the cost problem mentioned above.

Many digital humanities scholars and small museums and archives are unable to complete digital projects on their own. Further, even if they do manage to digitize their projects, they are often stored in isolated data silos incompatible with automatic processing and unable to search for related information. These limitations can be addressed by organizing and publishing data using standard formats and by adding structure and metadata to the content of the web pages and linking related data. However, this is not a trivial task, and many humanities scholars with non-technical background usually do not have the technical support to undertake such intricate work. Often this extra step requires complex setups and in many cases use of sophisticated, unfamiliar software.

These are some of the primary reasons that prevent the dissemination of cultural heritage content and over the Web, with the result that content “knowledge” remain unused and hidden. Many attempts and much research has, and continues to be, undertaken attempting to provide solutions to these problems. Still, the solution remains elusive, and as such, will be the focus of this paper.

Literature Review

There are many popular open-source dissemination solutions in the Cultural Heritage domain. In recent years, there has been an effort, dedicated to Cultural Heritage, in tailoring to a particular functionality of popular Content Management Systems (CMS). A great example is a work by Kim Christen and Craig Dietrich (Michael, 2014), developers of the Mukurtu CMS[5], an open source platform. The result is a flexible CMS to meet the needs of diverse communities that manage and share their digital cultural heritage online. The platform was developed on the leading open source Drupal[6] Content Management Framework. Further, it expands the functionality of the software towards the Cultural Heritage domain. The platform also supports international metadata standards, such as Encoded Archival Description (EAD), Machine Readable Cataloging (MARC) and Dublin Core (DC). The platform has been used in many indigenous archiving communities, as in a case study by Hall (2016) “Tribal Archives, Traditional Knowledge, and Local Context: Why the “s” Matters” (Christen, 2015), Christen explains how to use the system to archive and manage digital assets, and how to help local museums, archives, and libraries to manage, preserve, and reuse their digital Cultural Heritage.

A similar platform is OpenNumisma developed by A.Avgousti at The Cyprus Institute (CyI): Reusable web-based platform that merges digital imaging and data management and offers new opportunities for research and dissemination of knowledge and data (Avgousti et al., 2017). The development of OpenNumisma aims to create a digital web framework for numismatic collections, and it is implemented by small museums to digitize their numismatic collections. In 2018, the platform was deployed for the creation of a numismatic collection for the Medieval Coins from the Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation. One of the unique features of this platform is the application of Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), a computational photography method that offers tremendous image analysis possibilities for numismatic research (Alzua at al., 2005). Furthermore, system metadata is based on the popular Schema.org vocabulary, a semantic markup supported by major search engines that improves the sharing, discovery, and reuse of the data. It has also been used in the Cultural Heritage domain (Wallis, 2017), (Nuno et al., 2017, and Ronallo, 2012). The platform was developed on top of the Drupal CMS and it is available on GitHub. A similar idea was presented by Illias at al., (2012) in their research paper “A Drupal Module For Managing Museum Collections.”, where they present the problem of small museums unable to reach the public through the Web. Some of the reasons mentioned are the cost and the complexity of the development and customizations of such applications. In his paper Ilias, he recommends a different approach and the development of a module that will extend the functionality of a general purpose CMS towards museum collections. They also mention the lack of generic CMS which uses CIDOC-CRM[7] and Dublin Core metadata.

Alongside, the Drupal CMS is a powerful open source content management platform that is popular among humanities scholars (Dombrowski, 2016). The platform has core website functionality, such as taxonomy search and multilingual capabilities. Drupal also has a relatively high learning curve for non-coders who plan to build a site using the user interface. Drupal also has been used in support of digital collections and is the first major CMS that supports Semantic Web technologies in its core (Havlik, 2011). Lenneth Varnum’s book, Drupal in Libraries, covers how to build and maintain a library website using Drupal (Varnum, 2012). Matt Ostercamp described the implementation of Drupal as a CMS at Trinity International University Rolfing Library.

Along these lines, Quinn Dombroski recently published a book, Drupal for Humanists demonstrating how to use Drupal to develop small humanities projects (Dombroski, 2016). Athanasios Velios in his research paper “Off-the-shelf CRM” (Velios, 2016) introduced a new method of using the Drupal CMS in cultural heritage institutions to publish data in both human-understandable and machine-understandable formats using The Resource Description Framework in Attributes (RDFa) a flavor of the Resource Description Framework (RDF). Such data is suitable for machine consumption. Further, Athanasios Velios (Velios, 2011) in his research paper “The John Latham Archive: An online Implementation Using Drupal” demonstrates how the CMS can be used to create an archive system. Nowadays, Drupal powers an extensive infrastructure of digital cultural heritage projects (Dombrowski, 2016), like the Louvre website. The Smithsonian Libraries are using Drupal for the management and presentation of their content (Thompson et al., 2013), as are the Qatar Digital Library, the New York Public Library (Anderson et al., 2018) and many others.

Moreover, Constantinos Sophocleous (Sophocleous et al., 2017) describes in “Medici 2: A Scalable Content Management System for Cultural Heritage Datasets” a content management system for Cultural Heritage datasets. It is specialized for management analysis and visualization of CH research. It was developed by the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, the Library of Alexandria (BA) and the Cyprus Institute (CyI). Medici 2.0 can handle datasets in a variety of formats (3D, RTI) that are widely used in Cultural Heritage research. For metadata, the CMS used Dublin Core (DC) where metadata can be shared with the scientific community.

Also under the category of Collection Management Systems is the work of The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (RRCHNM), and George Mason University the developer of Omeka, a system developed specifically for scholars, librarians, archive, museums to create their digital exhibitions. Omeka was developed with the objective of helping institutions and organizations to manage and collaboratively discover their digital assets using recommended best practices. Omeka uses the Dublin Core for storing metadata about the objects. One of the most famous scholarly extensions of Omeka is Neatline, a plugin that adds geolocation functionality to an Omeka archive and allows the user to tell visual stories with maps and timelines. The recently released next-generation Omeka S is more oriented to connecting digital cultural heritage collections using Linked Open Data principles. Omeka has been used in many memory institutions and libraries (Hardesty, 2014). However, compared to large and robust ecosystems that are available for other large CMSs like WordPress, Joomla, and Drupal, Omeka[8] is fairly moderate and with small community support, plugins, developers, and users.

Another CMS similar to Omeka is WordPress. It started as an easy to use blogging system and became the system of choice for large and more complex websites (Vandegrift, 2013). It is free and open source and has a relatively low learning curve. Nowadays, WordPress powers the majority of the sites on the Web (Martinez et al., 2018). Extensions of WordPress can be used to consume museum collections management data. A great number of plugins have been developed by digital humanities to extend WordPress in more advanced ways beyond a simple web presence. DH press is a plugin that allows the users to create events, documents, people and develop links with a location map. Other plugins include CommentPress, a great text annotation tool for humanities researchers, and the Cultural Object plugin, which is more oriented to online museum collections and allows the easy pulling and consuming of museum collections management data.

Yet another choice for a CMS is the Islandora platform that was developed by the Robertson library of the University of Prince Edward Island’s, (Moses et al., 2013) and now has its implementation and maintenance under the responsibility of a growing international community (Martins et al., 2018). Its architecture is built on a base of other software such as Drupal CMF, Fedora, and Solr. Islandora[9] offers a set of solution packages that allow its users to manipulate various types of digital objects, such as images, videos, pdf, among others, and fields of knowledge (Perkins, 2015). These solution packages enable integration with other software, publishers, data-processing applications, and metadata schemas. At Vassar College, Islandora offers the students a unique experience by hosting students diaries from the early days of the college (Pasquale et al., 2013). Islandora is also beneficial if the institution wants to create an image repository. However, the development time is extensive. The Islandora system’s complexity and advanced customization usually require support from professional IT staff.

Justification of Technology

Our prototype applications are developed on top of the State of the art Content Management Framework Drupal (CMF) and the Schema.org Ontology. Due to the reasons outlined below, Drupal will be the CMF to use for our prototype system. However, the implementation of our methodology can apply to any other CMF/CMS.

The Drupal CMF was one of the first major systems to support Semantic technology in its core. More specifically, Drupal supports RDFa[10] which allows expression of structured data in markup languages. Also, it requires limited technical knowledge which allows non-technical individuals to easily publish, manage, and organize a variety of content. Over the past few years, Drupal has become very popular among humanities projects. (Dombrowski, 2016).

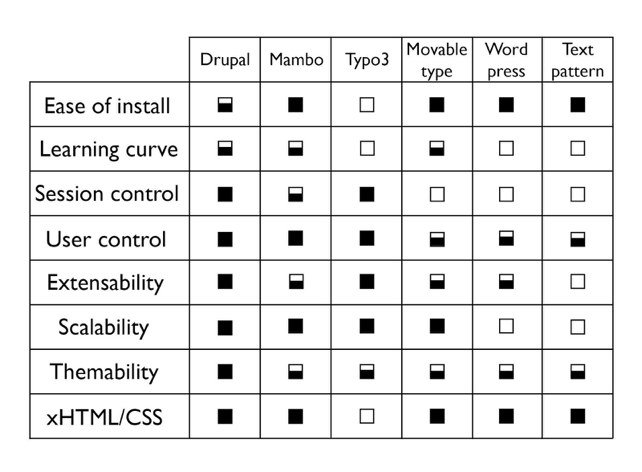

Moreover, it is open source software with the vital community of user and developers that usually comes with at no-cost, and some of the community groups are dedicated to humanities projects (Avgousti, 2018). A comparison made by IBM also shows the benefits of using Drupal among other CMSs (Weitzman et al., 2006) see Figure 1.

Figure 1.Content Management Systems Comparison

Adapted from: (Weitzman, et al, 2006)

[Full Box = Easy] [ Empty Box = Difficult] [Half Box = Medium ]

Why the Drupal Content Management Framework is appropriate to meet our goals:

- It has familiar tools with which non-technical researchers can publish data without expensive and extensive technical support

- It is a popular tool among humanities scholars and researchers

- A significant amount of digital humanities infrastructure is built upon Drupal

- A significant amount of Museum and Archival collections are using Drupal

- It is the first major CMF that supports Semantic Web technologies in its core

- It is free and open-source

- Community priorities: free web experience without the control of big industry giants

- Modular system, each module offering part of its functionality

- Large distribution ecosystem

- Philosophy: Software freedom, community ownership and intersectional politics to co-develop technologies

- Collaborative approach and large community support

- One of the most popular open-source general purpose Content Management Frameworks

Next we describe how Drupal is used by our methodology.

Community Reusable Semantic Metadata Content Models (RM’s)

Nowadays, humanities scholars willing to digitized their research projects can accomplish it by using existing open source platforms and without the need of hiring a computer specialist (Dombrowski, 2016). However, this process usually involves a steep learning curve, and a significant amount of time that generally humanities scholars do not have (Ilias Daradimos, 2015). Furthermore, they rarely take the extra step to embed structured data on their online projects, and their research is often stored in isolated data silos (Sikos, 2015).

We aim to develop Community Reusable Semantic Metadata Content Models (RM’s). The models will be a collection of reusable elements which taken together satisfy a particular case related to Cultural Heritage institutions. Examples: a) Numismatic Collections b) Photographic Collections c) Works of Art Collections d) Ancient Graffiti Collections, and so forth.

It would be sufficient to package, reuse and improve this functionality once and reuse it again and share it with others in a larger community.

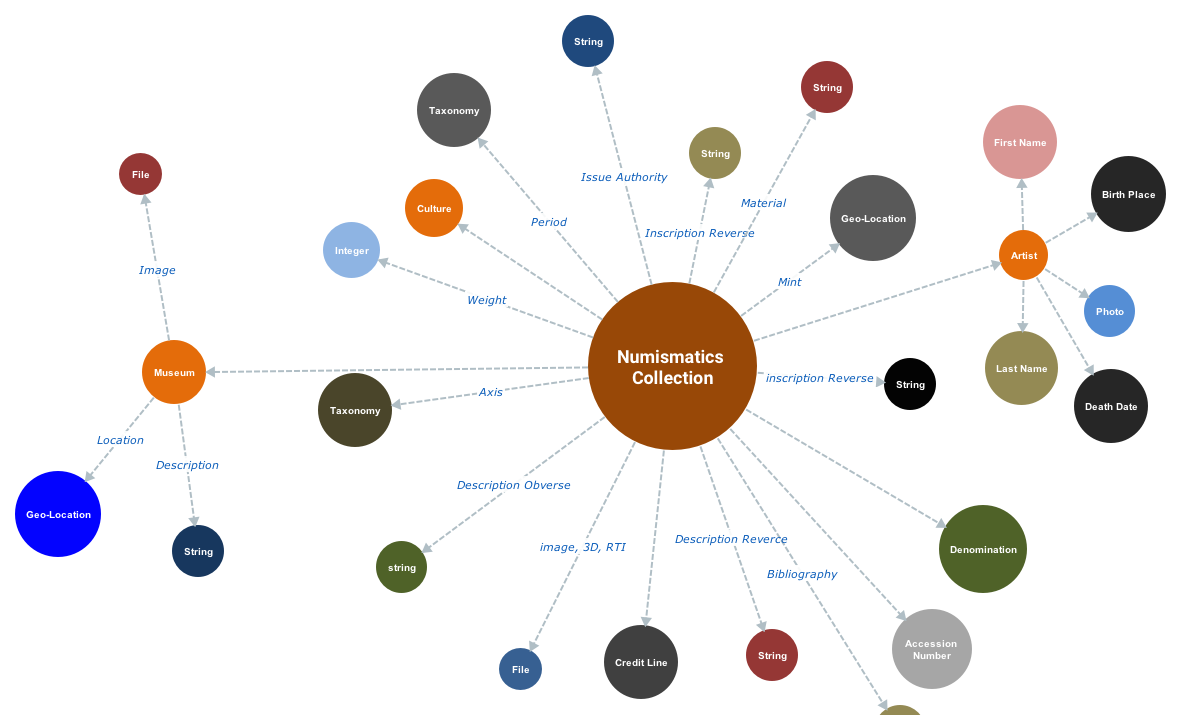

The following image represents an example of Community Reusable Semantic Metadata Content Models (RM’s). This Data model representing Ancient Graffiti, showing the complexity and the research required to create the data modeling and the systems architecture.

Figure 2.Example of RM’s Data Model [Representing Ancient Graffiti]

Adapted from : Mia Gaia Trentin, Post Doc Fellow at The Cyprus Institute Science and Technology in Archaeology Research Center (STARC)-NCSA University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign

The following list represents some of the fundamental advantages willing to achieve in cultural heritage domain by using Community Reusable Semantic Metadata Content Models (RM’s).

- To increase dissemination of content from small museum and archival collections

- To reshare, improve and upgrade RM’s

- To lower the complexity of the digitization process

- To reduce small scale museum and archives collections development complexity

- To increase the use of open-source applications in cultural heritage domain

- To reduce human errors

- To lower development costs

- To create labor-saving tools

- To minimize software complexity

- To expand semantic markup annotations

In this paper, we are introducing our first RM’s that are ready to use and downloaded from our website (https://rms.cyi.ac.cy). The RM’s available for download and installed with a few clicks, and it will extend the functionality of the Drupal CMF towards numismatic collections. Further, it encapsulates metadata using the RDFa format and uses the Schema.org vocabulary, supported by major search engines aiming to improve sharing, discovering and reusing of online content. In 2011 the major search engines (Google, Yandex, Bing, Yahoo) introduced the Schema.org (Jason, 2012 and (Guha, 2015) an Ontologies that is understandable to web crawlers and other machines (Shayna, 2018). Given the popularity of Search Engines, many content creators and site administrators will most probably integrate the Schema.org on their projects. Nowadays, the Schema.org already implemented in millions of websites and used by Cultural Heritage organizations like Europeana (Wallis, 2017).

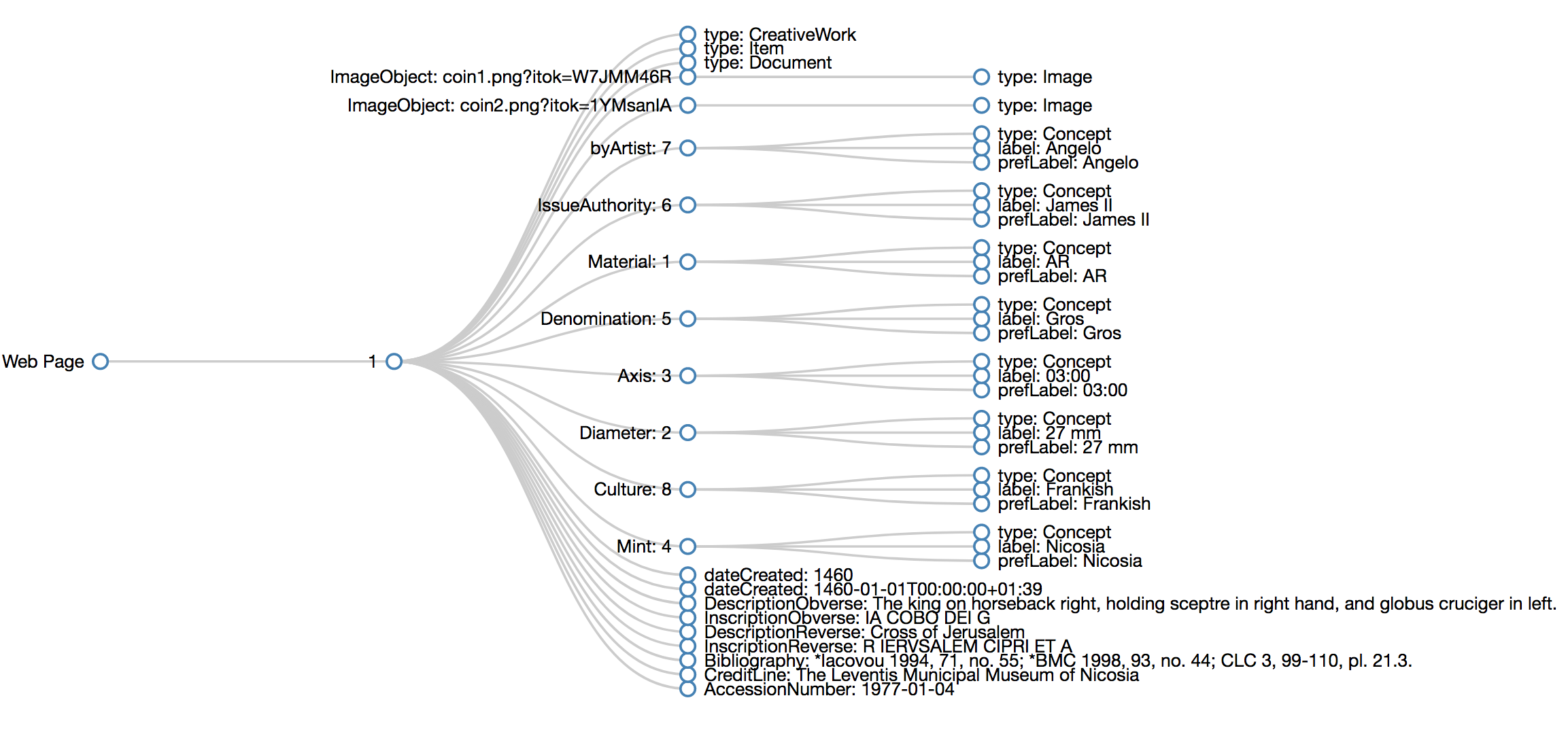

Figure 3. RM’s Data Modeling-Numismatic Collections

Further, by downloading and installing, the RM model will generate a pre-defined collection of data types known to Drupal as “fields” which are related to each other by an informational context. The pre-defined collection of data types were developed to support an online numismatic collection data model. All the fields were selected in and with research, collaboration and in a joint effort with numismatic experts. While there is no single perfect data model for a given case study, this data model was developed very carefully, and with the confidence that it will cover a good percentage of the needs of a small numismatic collection project. Furthermore, the option of extending and improving the model by adding more functionality it’s always welcomed, and it is the aim of our future community. Each field also uses the Schema.org Ontology to add structured metadata embedded in every HTML page generated. With that, all major search engines (Google, Yandex, Bing, etc) understand the published content more efficiently.

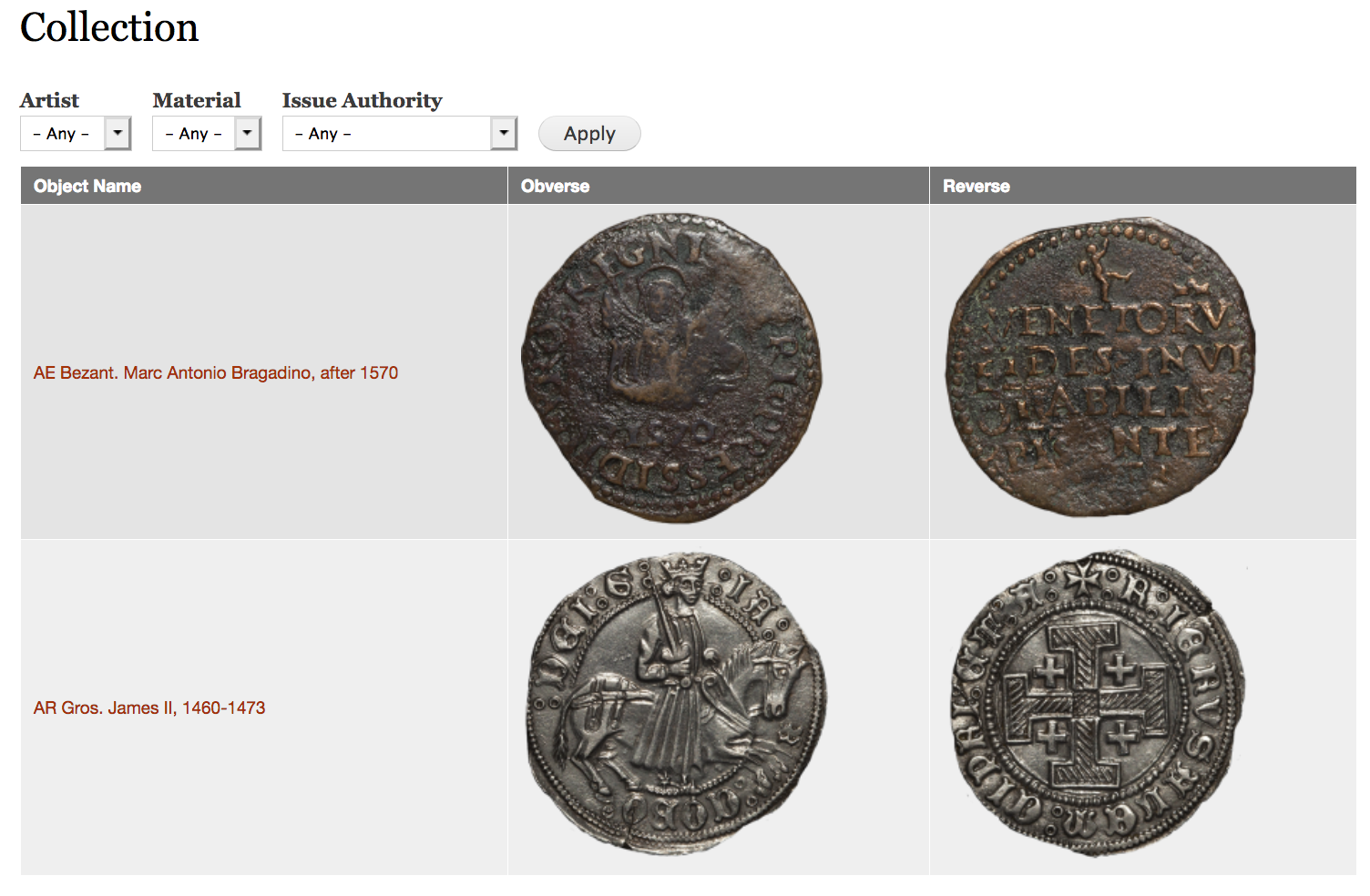

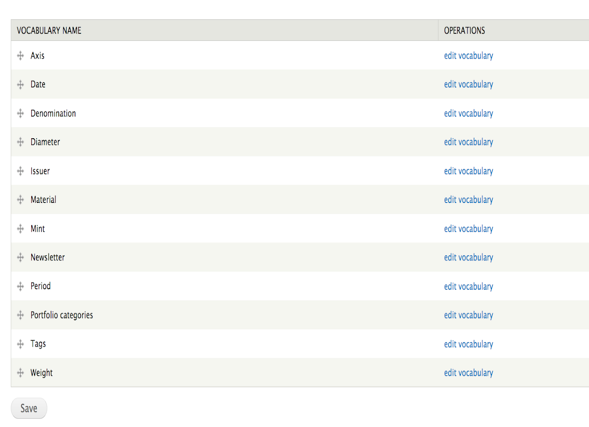

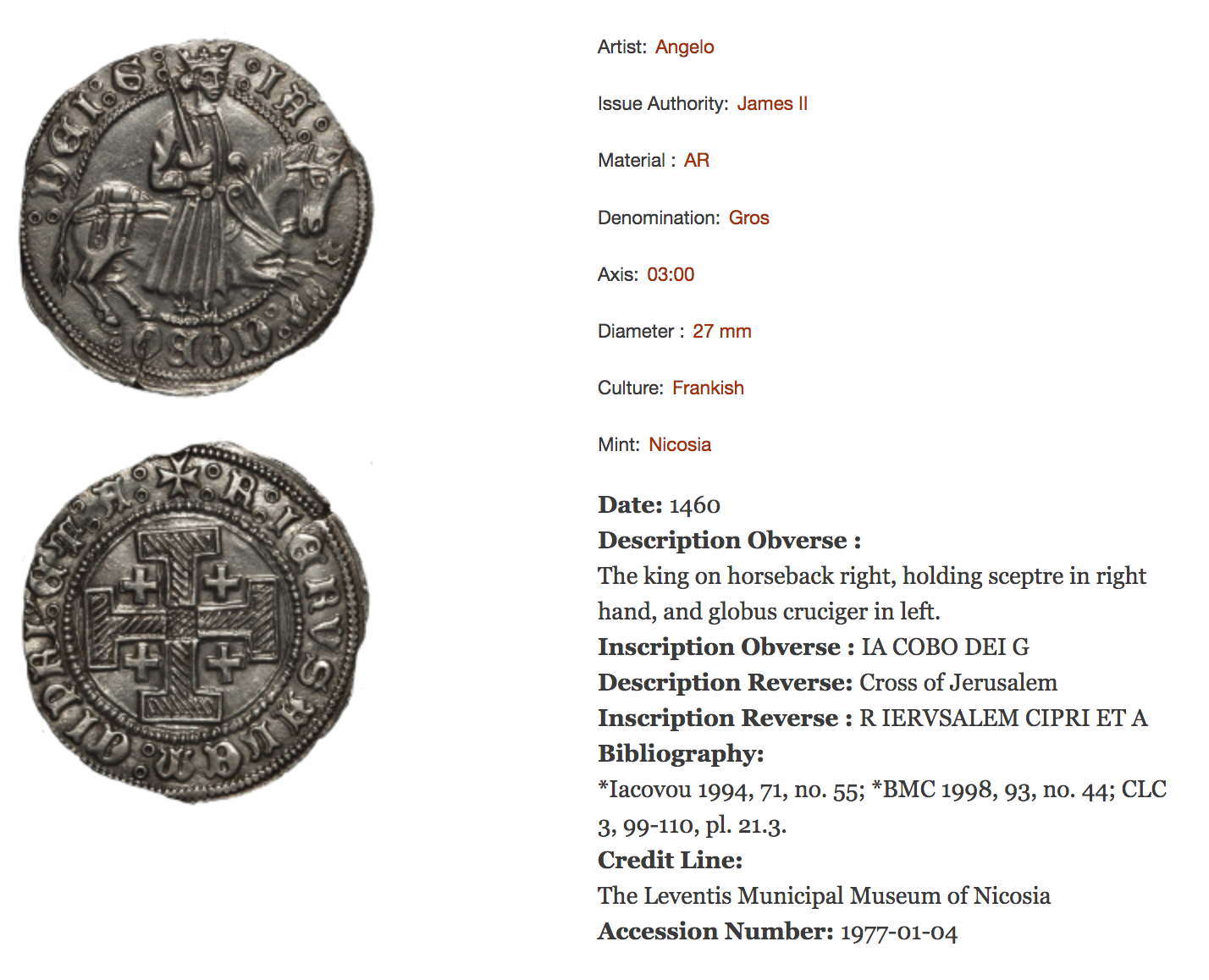

Figure 4. Example of Generated Pre-Defined collection of Data Types

Installing the RM’s will automatically generate and display a list of content that will be able to present all the collection in the form of a list or table. Moreover, it creates filters for easy information retrieval where the user can filter down the information by using the Artist, Material, and Issue Authority. The RM also generating taxonomical vocabularies and allow the end user to populate them with terms, for example, Axis, Mint, Weight, etc. Taxonomic terms can be used to classify content, and in this case, probably the most important use is to relate content. For example, searching for all coins that have Weight 1.73 mm the system will be able to locate coins based on the specific taxonomic term. Also, it automatically creates a display template, where the images are shown on the left and the information about the images on the right (see Fig: 6). With that users can easily read the content and at the same time view the images.

Figure 5. List of All Coins Collection Sort by Taxonomy (Medieval coins from the Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation collection)

|

|

Figure 6. Generated pre-defined collection of taxonomic categories

|

|

Figure 7. Left: HTML page (Medieval coins from the Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation collection). Right: A real-time RDFa, Data Visualizer using RDFa Play tool

Applicability

The first successful implementation of Community Reusable Semantic Metadata Content Models (RM’s-Numismatics) was implemented for the development of a kiosk website installation at the Leventis Municipal Museum in Nicosia, Cyprus, hosting a numismatic collection of about 125 coins. (http://coins.cyi.ac.cy)

The second request came from The Fluminense Federal University in Brazil willing to see the possibility of using our RM’s-Numismatic for their online collection.

Conclusion and Future work

Establishing an Online Community

The broader idea is to establish an online community “An online community is a group of people with common interests who use the Internet (websites, email, instant messaging, etc.) to communicate, work together and pursue their interests over time”(“What Is An Online Community?” 2018)”.

Some of the reason of the development of an online community for Community Reusable Semantic Metadata Content Models (RM’s) is to allow digital humanities scholars, site builders, computer scientists, digital humanities, site administrators, web developers, and so forth to create, develop, collaborate, improve, upgrade and share their models, packaged for the benefit of the Cultural Heritage community.

A distributed model for Community Reusable Semantic Metadata Content Models will allow our community to grow and be more flexible, serve more needs and give the infrastructure to scale for the next generation of humanities scholars.

Step 1: Develop Community Reusable Semantic Metadata Content Models that will cover other areas of museum and archives collections. Example: Photographic Collections, Folk Collections, and so forth.

Step 2: We already created the first version (beta version) of our community website (https://rms.cyi.ac.cy) that will allow members of the community to share Community Reusable Semantic Metadata Content Models. In the site, users can learn about RM’s and able to download and use our first module describe in this paper.

Step 3: Is to create a email-list, forum and discussion group, where members can share ideas and discuss the further development of new or existing RM’s. For example, development of a new RM that will cover a new area in Cultural Heritage, or improve an existing RM’s with more functionality either create a new one that will extend the functionality of an existing one.

Step 4: We are planning to have an upload session to register users, where they can upload their own RM’s, to share them with the rest of the community. The new uploaded RM’s will be first tested and only then published online.

Step 5: Disseminate the existence of our community by attending conferences, events related to Cultural Heritage and technology conferences.

Dissemination: Conferences and Events Attended

- ICOMON 2018 “Building A Digital Platform for Numismatic Collections” Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece

- Drupal Hack Camp 2018 “Drupal and Schema.org in the Semantic interoperability of Cultural Heritage Knowledge” Bucharest, Romania

- Library of Alexandria 2017 “ Digital Library for Cultural Heritage” Alexandria, Egypt

- Oxford University 2016 “Platform for numismatic collections” Oxford, England

- United Nations Headquarters 2015 “Drupal for Cultural Heritage” New York, USA

|

|

Figure 8.: Left: Web-Community Reusable Semantic Metadata Content Models. Right: RM’s Package Model

About the Authors

Avgoustinos Avgousti (a.avgousti@cyi.ac.cy) is a Research Technical Specialist at The Cyprus Institute at the Science and Technology in Archaeology Research Center (STARC). He is the web Architect and lead developer of Dioptra: The Digital Library for Cypriot Culture. He received his Bachelor of Science (BSc) from St. Francis College in New York City in Information Technology/Computer Science and Master of Science (MSc) in Medical Informatics from the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in New York City. He has more than 12 years of experience in Information Technology and 3 years of teaching Computer Science at a college level. Furthermore, he participated in a number of EU and national funded projects. Avgoustinos’ research activity has been focused in the last five years on Digital Humanities and Digital Cultural Heritage.

Dr Georgios Papaioannou is an Associate Professor for the MA in Museum and Gallery Practices University College London (UCL) Qatar. His research interests lie in museology, archaeology of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Arab World, education (including e-learning), tourism (including city tourism), cultural studies and IT applications, including virtual reality, augmented reality, Big Data and mobile applications. He has lectured, excavated, led tours and conducted museum / cultural heritage work in the UK, Greece, Italy, Albania, Cyprus, Sweden, Australia, Spain, Egypt, Syria, Oman, Turkey, Yemen and Saudi Arabia. Dr Papaioannou is General-Secretary of the Hellenic Society for Near Eastern Studies, Director of the Museology Lab in Corfu (Greece) and a member of ICOM.

Dr Feliz Ribeiro Gouveia (fribeiro@ufp.edu.pt) is currently an Associate Professor of Computer Engineering at the Faculty of Engineering of University Fernando Pessoa, Porto, Portugal. He has worked in research and technology transfer projects for industry, in the areas of knowledge management and object-oriented databases for major european companies. He participated in several research projects in cultural heritage and digital humanities and has acted as consultant for organizations implementing cultural collection management projects. He graduated in Electrotechnical Engineering from the University of Porto and holds a PhD in Computer Science from the Université de Technologie de Compiègne, France.

Notes

[1] https://www.europeana.eu/portal/en

[2] https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection

[3] https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

[4] https://html.com/semantic-markup

References

Alzua-Sorzabal, Aurkene and Linaza, Maria teresa, and Abad, Marina, and Arretxea, Larraitz, and Susperregui, Ana. 2005. Interface Evaluation for Cultural Heritage Applications: The Case of FERRUM Exhibition. The 6th International Symposium on Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Cultural Heritage. Vol. VAST. doi:10.2312/VAST/VAST05/099-106.

Anderson, Jennifer L, and Edwin Guzman. 2018. “Adaptation: The Continuing Evolution of the New York Public Library’s Digital Design System.” Code4Lib Journal, issue 41. https://journal.code4lib.org/articles/13657

Avgousti, Avgoustinos, Andriana Nikolaidou, and Ropertos Georgiou. 2017. “OpeNumisma: A Software Platform Managing Numismatic Collections with A Particular Focus On Reflectance Transformation Imaging.” Code4Lib Journal, issue 37. https://journal.code4lib.org/articles/12627

Brawley-Barker, Tessa. 2016. “Integrating Library, Archives, and Museum Collections in an Open Source Information Management System: A Case Study at Glenstone.” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America. doi:10.1086/685979.

Butkiewicz, Michael. 2011. “Understanding Website Complexity?: Measurements , Metrics , and Implications Categories and Subject Descriptors.” Proceedings of the 2011 ACM, 313–28. doi:10.1145/2068816.2068846.

Christen, Kimberly (2015) “Tribal Archives, Traditional Knowledge, and Local Contexts: Why the “s” Matters,” Journal of Western Archives: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/westernarchives/vol6/iss1/3

Cimadomo, Guido. 2013. “Documentation and Dissemination of Cultural Heritage: Current Solutions and Considerations about Its Digital Implementation.” Proceedings of the DigitalHeritage 2013 – Federating the 19th Int’l VSMM, 10th Eurographics GCH, and 2nd UNESCO Memory of the World Conferences, Plus Special Sessions FromCAA, Arqueologica 2.0 et Al. 1: 555–62. doi:10.1109/DigitalHeritage.2013.6743796.

Corlosquet, Stéphane, and Cyganiak, Richard, and Polleres, Axel, and Decker, Stefan. 2009. “RDFa in Drupal: Bringing Cheese to the Web of Data.” CEUR Workshop Proceedings. https://aic.ai.wu.ac.at/~polleres/publications/corl-etal-2009.pdf

Daradimos, Ilias, and Vassilakis, Costas Vassilakis, and Katifori, Akrivi. “A Drupal CMS Module for Managing Museum Collections.” Conference Paper, March 2015.

Di Pasquale, J., and Palmentiero, J., and Streett, L. (2013), “Using archives and metadata to uncover women’s lives: Challenges and opportunities for scholarship through archives and digital libraries”, paper presented at the Women’s History in the Digital World conference, 22-23 March, at Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, available at: https://repository. brynmawr.edu/greenfield_conference/papers/saturday/22/

Dombrowski, Quinn. Drupal for humanists. Texas A&M University Press, 2016.

Flake, Gary William, and Lawrence Steve, and Giles, C. Lee. “Efficient Identification of Web Communities.” Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, August 20-23, 2000, pp. 150-160. doi: 10.1145/347090.347121

Freire, Nuno, and Charles, Valentine, and Isaac, Antoine. “Evaluation of Schema.org for Aggregation of Cultural Heritage Metadata.” Gangemi A. et al. (eds) The Semantic Web. ESWC 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 10843. Springer, Cham. https://www.inesc-id.pt/publications/13560/pdf/

Gasparotto, Melissa. 2014. “Search Engine Optimization for the Research Librarian: A Case Study Using the Bibliography of U . S . Latina Lesbian History and Culture.” Practical Academic Librarianship: The International Journal of the SLA Academic Division. Volume 4, n. 1, June 2014, pp. 15-34. https://journals.tdl.org/pal/index.php/pal/article/view/6971.

Guha, R. V., and Brickley, Dan and MacBeth, Steve. “Schema.Org:

Evolution of Structured Data on the Web.” Queue 13 (9), Nov. 2015. doi:10.1145/2857274.2857276.

Havlik D. 2011. Building Environmental Semantic Web Applications with Drupal. In: H?ebí?ek J., Schimak G., Denzer R. (eds) Environmental Software Systems. Frameworks of eEnvironment. ISESS 2011. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, vol 359. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-22285-6_42.

Kawano, H. 2012. Digital Archive system using CMS and Gallery tools –implementation of Anthropological Museum. https://www.cut.ac.cy/euromed2012proceedings/shortPapers/125.pdf

Hardesty, Juliet L. 2013. “Exhibiting Library Collections Online: Omeka in Context.” New Library World 115 (3–4): 75–86. doi: 10.1108/NLW-01-2014-0013.

Martinez-Caro, Jose-Manuel, and Aledo-Hernandez, Antonio-Jose, and Guillen-Perez, Antonio and Sanchez-Iborra, Ramon, and Cano, Maria-Dolores. 2018. “A Comparative Study of Web Content Management Systems.” Information 9 (2): 27. doi: 10.3390/info9020027.

Matt Ostercamp, 2010 “A New Way to Create a Website: Using Drupal to Create a Dynamic Web Presence.” American Theological Library Association Summary of Proceedings 64 (2010): 139-147.

Moses, Donald, and Stapelfeldt, Kirsta. 2013. “Renewing UPEI ’ s Institutional Repository: New Features for an Islandora-Based Environment.” Code4Lib Journal, issue 21. https://journal.code4lib.org/articles/8763

Murugesan, San, and Yogesh Deshpande. 2005. “Web Engineering: Introduction and Perspectives.” Web Engineering – Managing Diversity and Complexity of Web Application Development 2016: 1–2. doi:10.1007/3-540-45144-7.

Pantoja, Javier, and Docampo, Javier, and Martín, Ana, and Maturana, Ricardo Alonso, and Navalón, Carlos (2016). The New Prado Museum Website: A semantic challenge. Retrieved April 6, 2018: https://mw2016.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/the-new-prado-museum-website-a-semantic-challenge/

Perkins, Stephen. 2015. “Introduction to Islandora.” Infoset Digital Publishing. http://www.infoset.io/articles/introduction-to-islandora.

Ronallo, Jason. 2012. “HTML5 Microdata and Schema.Org.” Code4Lib Journal, issue 16. https://journal.code4lib.org/articles/6400

Royce, Dr. Winston W. 1970. “Managing the Development of Large Software Systems.” Ieee Wescon, no. August: 1–9.

Shepard, Michael. “Review of Mukurtu Content Management System.” Language Documentation & Conservation, vol. 8, 2014. pp. 315-325.

http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24610

Stainforth, Elizabeth. 2016. “From Museum to Memory Institution: The Politics of European Culture Online.” Museum & Society. 14 (2): 323–37.

Samis P.S., Johnson, L.F. and Smith, R.S. (2007), “Pachyderm: From multimedia to visual stories.” Journal of Computing in Higher Education, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 3-25.

Scholz, Martin, and Guenther Goerz. 2012. “WissKI: A Virtual Research Environment for Cultural Heritage.” Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications, 242: 1017–18. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-098-7-1017.

Sikos, Leslie F. Mastering Structured Data on the Semantic Web. 1st ed. Apress, 2015.

Sophocleous, Constantinos. 2017. “Medici 2: A Scalable Content Management System for Cultural Heritage Datasets” Code4Lib Journal, https://journal.code4lib.org/articles/12317

Thompson, Keri, and Joel Richard. 2013. “Moving Our Data to the Semantic Web: Leveraging a Content Management System to Create the Linked Open Library.” Journal of Library Metadata, doi:10.1080/19386389.2013.828551.

Tongue, Charles. 2018. “Museum Survey 2017 – Vernon Systems.” Vernon Systems. https://vernonsystems.com/museum-survey-2017/.

Vandegrift, Micah, and Stewart Varner. 2013. “Evolving in Common: Creating Mutually Supportive Relationships Between Libraries and the Digital Humanities.” Journal of Library Administration, 53 (1): 67–78. doi:10.1080/01930826.2013.756699.

Varnum, Kenneth J. Drupal in libraries. London: Facet, 2012.

Vavliakis, Konstantinos N. and Karagiannis, Georgios and Pericles, Mitkas A. “Semantic Web in Cultural Heritage After 2020.” Conference: 11th International Semantic Web Conference 2012 (ISWC 2012)

Velios, Athanasios. “The John Latham Archive?: An on-Line Implementation Using Drupal.” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, Vol. 30, No. 2, Fall 2011, pp. 4-13.

Wallis, Richard, and Isaac, Antoine and Charles, Valentine, and Manguinhas, Hugo. 2017. “Recommendations for the Application of Schema.Org to Aggregated Cultural Heritage Metadata to Increase Relevance and Visibility to Search Engines: The Case of Europeana.” Code4Lib Journal, April 2017. http://journal.code4lib.org/articles/12330.

Weist, J. (2010), “Implementing collective: access at the Bruce high Quality Foundation University Archive.” Visual Resources Association Bulletin, Vol. 37 No. 2, pp. 23-26.

Weitzman,Louis, and Lewis-Bowen, Alister, and Evanchik, Stephen. Using open source software to design, develop, and deploy a collaborative web site, part 1: Introduction and overview. July 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20070901123433/http://www-128.ibm.com:80/developerworks/ibm/library/i-osource1/index.html

“What Is An Online Community?”. 2018. Common Craft. https://www.commoncraft.com/archives/000208.html.

Whysel, Noreen. 2014. “A Survey of Digital Humanities Skillshare Applications.” doi:10.7916/D8571903

Wiltshire, N G. “THE USE OF SAHRIS AS A STATE SPONSORED DIGITAL HERITAGE REPOSITORY AND MANAGEMENT SYSTEM IN SOUTH AFRICA.” ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume II-5/W1, 2013. XXIV International CIPA Symposium, 2 – 6 September 2013, Strasbourg, France. https://www.isprs-ann-photogramm-remote-sens-spatial-inf-sci.net/II-5-W1/325/2013/isprsannals-II-5-W1-325-2013.pdf

Subscribe to comments: For this article | For all articles

Leave a Reply